Article by: Aysha El-Shamayleh

Sitting Editor: Eliza Marks

Photographs by Raneem Al-Daoud

Photographer’s assistant: Ghassan Jaradat

Styled and art directed by: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

Make-up: Luca Simone

Digital art work by: Atef Daglees

Behind the scenes video: Ala’a Abu Qasheh and Mustafa Rashed

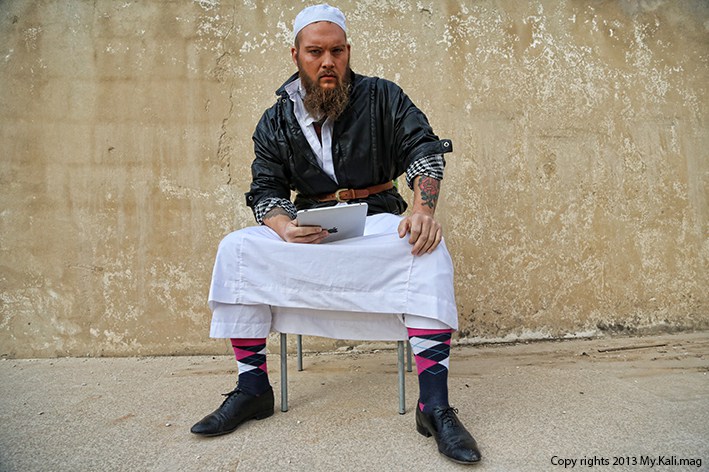

Modeled by Tony Streeter and Nadine S.

Religion. Some say it’s a private affair and an inner spirituality that must remain separate from public life. Others believe that their idea of God and favorite scripture should be displayed openly.

Your fashion, a hijab, a cross or an “Allah” pendant, and the length of a beard, are decisive markers of religious affiliation. In today’s world, many believe that it would be hypocritical to be devout and concerned with one’s appearance. fashionable. Generally speaking, both fashion and religion are aspects of individual identity. What people wear (their fashion) expresses their principles, affinities, and attitude towards life to the outside world, and religion is internal to a certain extent. Yet, many religions, especially Islam, have dress codes that determines one’s attire, and symbols that hold great significance. Would it be hypocritical to be both devout and concerned with fashion?

Of course, bias comes into play when answering this question. One realm where this comes into play is debates about the Hijab. Many argue that the purpose of wearing the hijab is to maintain modesty and detract attention. Surat An-Nur, verses 30-31, from the Quran, as translated by renowned Muslim scholar, Yusuf Ali, summarizes Islam’s opinions on proper women’s wear:

Say to the believing men that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty: that will make for greater purity for them: And Allah is well acquainted with all that they do. And say that the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what (must ordinarily) appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers or their brothers’ sons, or their sisters’ sons, or their women, or the slaves whom their right hands possess, or male servants free of physical needs, or small children who have no sense of the shame of sex.

In a nutshell, Islamic teachings instruct women to cover their bodies and hair, except for the hands, feet and face. The verse above requires a woman to dress “modestly”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, to be modest is to “be unassuming or moderate in the estimation of one’s abilities or achievements” or to “dress or behave so as to avoid impropriety, especially to avoid attracting sexual attention.”

This becomes complicated when you consider that in some spaces in the Arab World, being a woman in itself draws sexual attention. I leave it to you to define the parameters of “immodest clothing,” and I refrain from doing it myself due to my gender-politics, and my many objections against social and religious authorities that have justified rape by deeming victims’ clothing as provocative.

Others, myself included, believe clothing is a form of self-expression, and has been so for centuries. Women who follow a creed, whether it’s Islam or another religion, have a right to choose their dress and to dress well. Having respect for a deity does not require a woman to completely silence her beauty. In fact, the hijab is one example among a myriad.

But regardless of one’s opinion on the Hijab, it has become major in the growing religious-inspired fashion industry. This is a multi-million dollar industry in the Middle East, and major designers continue to cater their art to the needs and preferences of religious elite. The world’s most expensive Abaya was designed by late Princess Diana’s favorite British designer, Bruce Oldfield, whose client list spans generations – from icons including Queen Rania of Jordan and Sienna Miller, to Jemima Khan and Rihanna. And according to Trendhunter.com, the price-tag of that Abaya is $350,000. This particular Abaya has 359.7 grams of white gold and 4,668 individual diamonds. In June of 2011, Turkey’s high-fashion magazine, Âlâ, featured models wearing Coco Chanel headscarves for the first time. The reaction? The magazine’s circulation quadrupled to 40,000 in four months.

Welcome to reality; there is a growing Islamic bourgeoisie, which includes women who refuse to be excluded from the fashion world and they’ve got the money to demand a change. Since money makes the world go round, Middle Eastern and foreign designers alike are flocking to grab these market shares.

By any standards white gold and diamonds are extravagant accessories (i.e. ornaments), and when used as mere decorations on Abayas the wearer is being far from “modest.” But is a reasonable sense of fashion that adheres to the Muslim code immodest?

Consider a different example. In this part of the world, androgynous fashion “draws attention.” Are blazers and trousers “immodest”? I find it ridiculous to say so. By the same token, women who wear the hijab are not “immodest” if they cover while still follow fashion trends.

The topic of fashion and how it adapts to religion is not limited to women. A second example of religion and fashion comes into play when we talk about tattoos. Practicing Muslim men (and women) have tattooed “Allah” and Ayat from the Quran on their bodies for at least as long as I’ve been around, a practice also common among Christians According to a Hadith recorded by Bukhari, tattoos are impermissible in Islam. “It was narrated that Abu Juhayfah said: ‘The Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) cursed the one who does tattoos, and the one who has a tattoo done.’” This says that, according to Islam, tattoos are a form of mutilation that violates the sanctity of the body. However, there are also alternative interpretations, and some even question the validity of Hadiths altogether, because the sayings have been passed down for generations and have been susceptible to human error.

So, is it wrong to be a Muslim and have a tattoo? If you believe in Hadith, then yes, you are blatantly breaking a rule among a body of rules you claim to follow. However, while some Muslims believe the Quran is timeless, others believe that the world has evolved since the scripture was revealed, and hence some rules are no longer relevant or must be reinterpreted. Many religions of the Book contain verses that condone things that we now consider categorically wrong, such as slavery. However, to argue that the Hadith against tattoos no longer applies today is a difficult case to make. Unless you do not believe in Hadith, I would say that it would be contradictory to consider yourself a practicing Muslim and have tattoos. Mind you, I am a woman with tattoos raised in a Muslim household but does not identify as Muslim… lots of contradiction. (says the girl who was raised in a Muslim household and who does not identify as Muslim, yet has got the tattoos. So much for contradiction.)

This debate about the relationship between fashion and religion is neither limited to Islam nor exclusive to the Middle East. In fact, this phenomenon is even more pronounced in the West. Religion-inspired fashion is an empire of its own. It makes appearances on high-end designers’ runways and often igniting heated debates intentionally.

“Most people have distanced themselves from religion, because they do not stand for war over God. Religion used to be considered too holy to be criticized or represented in art or fashion.”

In January of 1989, the highly popular Madonna recorded a new album that was a mixture of personal ballads and celebratory dance tunes, “Like A Prayer.” Where’s the controversy? Madonna, who is notorious for using religious symbology in her music and fashion, received a vicious backlist following the release of the “Like a Prayer” music video. In the video, Madonna witnesses a murder, runs into a church in a brown slip, kisses a statue of a saint, makes love with a black man on a church pew, dances in front of burning crosses, sings with a church choir, and shows bleeding stigmata on both palms as though she had survived a crucifixion. The video was full of religious symbology, and many were offended by the content and considered it sacrilegious. Catholic groups in Italy staged full protest until the Pope released a statement banning Madonna from appearing from Italy. Mixing religion and fashion is unacceptable in the West, too.

Yet 2013 winter collections continue to feature Celtic cross patterns on casual leggings, shirts, earrings and sweaters. “Jesus is my homeboy” t-shirts are in style. Religious symbols are hip, and they are worn by those who practice and mostly by those who don’t.

Dolce & Gabbana turned their sights to the religious imagery that Sicily had to offer, looking to Italy’s rich history. The duo, Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, branded their first fine jewelry line. The line and the campaign were inspired by the traditional and superstitious lifestyle on the Italian islan. The designs exude sexual and passionate vibes, with a cross (no pun intended) between holy and erotic. The designs are traditional and religious, adorned with visions of angels, rosaries and the Madonna. The line includes bracelets, necklaces and pendants constructed of yellow, white, and rose gold, set with rubies, sapphires and pearls on Byzantine chains, and is intended to symbolize the emotions that a woman feels while she wears the jewelry. Italian models Bianca Balti and Simone Nobili were featured portraying this intention in a scandalous video campaign, in which Balti wears chandelier earrings while she acts the story of a passionate affair between the two young lovers. At the end of the video, Balti is in a state of remorse in the confession room; a statement of faith, and a wave of passion.

The quick uptick of these trends may seem to expose superficiality, but, I would argue that the issue is more complex. Our generation bore witness to 9/11, the war on Iraq, the war on Afghanistan, Islamophobia in the West, the rise of Al Qaeda in the East, the Arab Spring and the rise of Islamist powers. This is not to say that these events offer accurate representations of institutionalized religion, but to assume that the over-politicization of religion has not changed perceptions of creed and alienated people is unreasonable. Most people have distanced themselves from religion, because they do not stand for war over God.

Religion used to be considered above criticism, and mere humans were unable to capture it accurately… untouchable. We are now see these premises overturned, religious symbols entering mainstream culture, and their resultant loss of meaning. The Church that used to have supreme authority in the West is now marginalized, and the cross has become a hip symbol of nostalgia for a romanticized past. In the East, mosques were primarily places of education and discipline, but are now appreciated as cultural element, their minarets and calls for prayer are seen for their aesthetics rather than religious indicators..

We have to accept that religion-inspired fashion is sought after, now, and that religious symbols and iconography are now a figment of the past and something “vintage,” rather than an instrument to further one’s spiritual practice. It doesn’t mean we have to like or accept it. Religion and fashion will continue to clash for ages to come because of the fundamentally different understandings of the same material culture. The question of whether we are becoming hypocritical will come up time and time again; each of us must craft an alibi.

Read Tony’s blog entry about his experience with shoot ‘Tastes Like Religion’ (here)

Watch My.Kali’s mini-film of ‘Tastes Like Religion’