Words by Khalid Abdel-Hadi

Photography by Zaid Allozi

Cover design by Nawal Elzombie

Styling by Jad Toghuj

Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar

Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This piece is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Note: This article draws on select pop divas and performers as case studies to explore a broader cultural narrative. The choices are not exhaustive, nor do they intend to rank or diminish the significance of other artists whose works have equally left a mark. Many iconic figures, with vast fan bases and enduring legacies, may not appear here simply due to the scope and focus of this piece. Their absence is not a reflection of their value, but rather a limitation of format. Their contributions are deeply acknowledged, respected, and adorned.

The term “diva” itself is elastic, shaped by regions, eras, and social contexts. This article does not seek to pin down a universal definition of the diva, but rather to engage with the affective power these women have held over queer Arab audiences, especially during a specific media moment defined by satellite television, magazines, music videos, and pan-Arab pop culture.

There is a peculiar phenomenon that persists among LGBT+ Arabs communities across the Arabic speaking region and diaspora: a deep-rooted obsession, almost veneration, of the pop divas of the 1990s and 2000s. These figures live on as cultural saints in the queer imagination, not merely as celebrities but as icons, muses, and in some cases, liberators. The devotion to them has not waned, even as younger generations come of age in the era of TikTok, Spotify algorithms, and digital hyper-fragmentation. If anything, the reverence has grown, transformed into a kind of nostalgic aesthetic language that bridges queerness, memory, and Arabness, and contributed to archiving their works.

As I write about these icons, I am aware that I am also writing nostalgically about a unified commercial media structure, one in which I did not fully partake in, yet one that shaped my cultural memory. That era, while often romanticized, was far from innocent; it was deeply embedded in heteronormative ideals and catered to the male gaze, heavily relying on glamour, zooming on body parts, hypersexuality, and the commodification of “dala3/dalaa” (coquetry or simper). It was an era shaped as much by repression and manipulation as by artistry, and one that also affirmed generalized stereotypes often circulated around LGBT+ folks. Another way to interpret these music videos, as Correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor, Samar Farah, suggests in her article “Women Rock the Casbah,” is that “they offer images of strong and independent Arab women willing to make unabashed declarations of desire.”1

What becomes clear, especially when tracing queer reverence for these women, is the diversity of eras and aesthetics they represent. Nelly and Sherihan, both icons of a golden era of televised entertainment, defined the 70s, 80s, and early 90s with their theatrical brilliance and unforgettable Ramadan specials. Sherihan, in particular, was ahead of her time in her aesthetics, which were, in my view, later echoed by Western performers such as Lady Gaga.

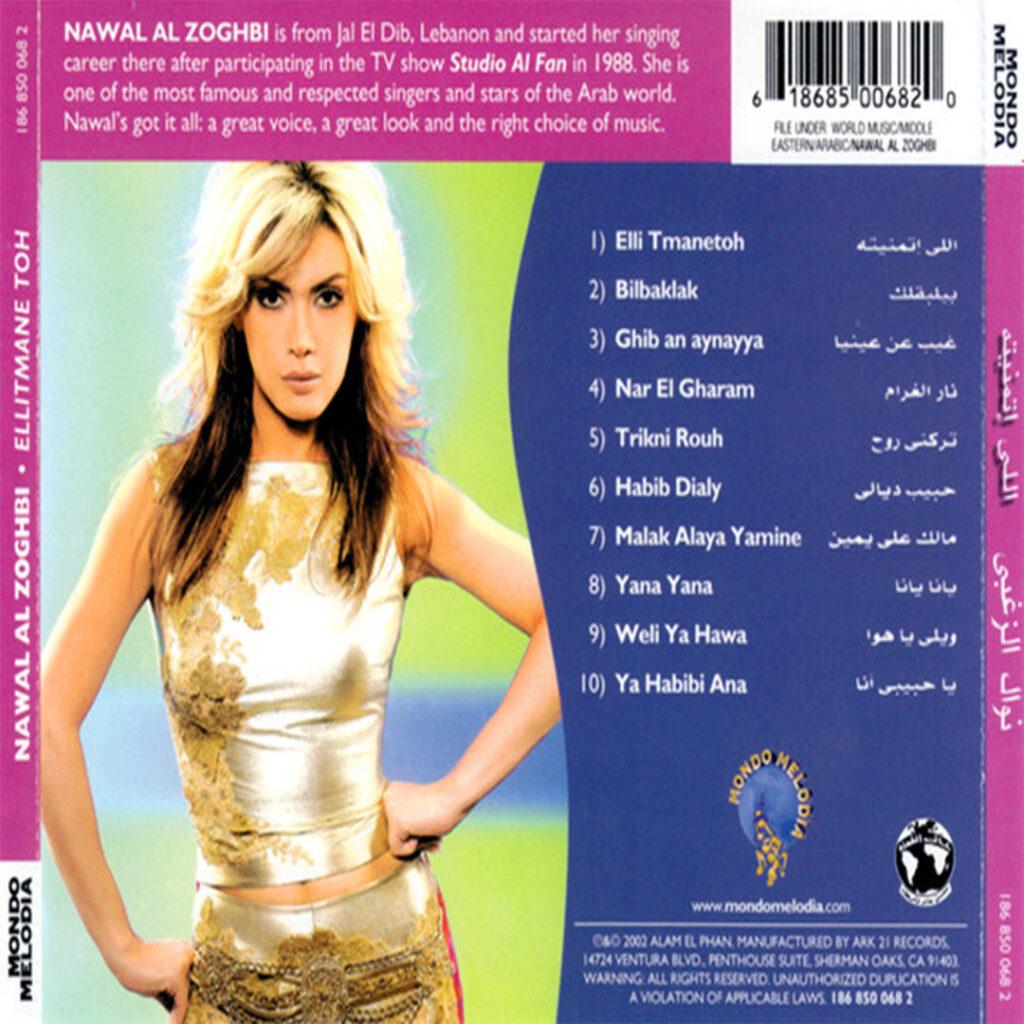

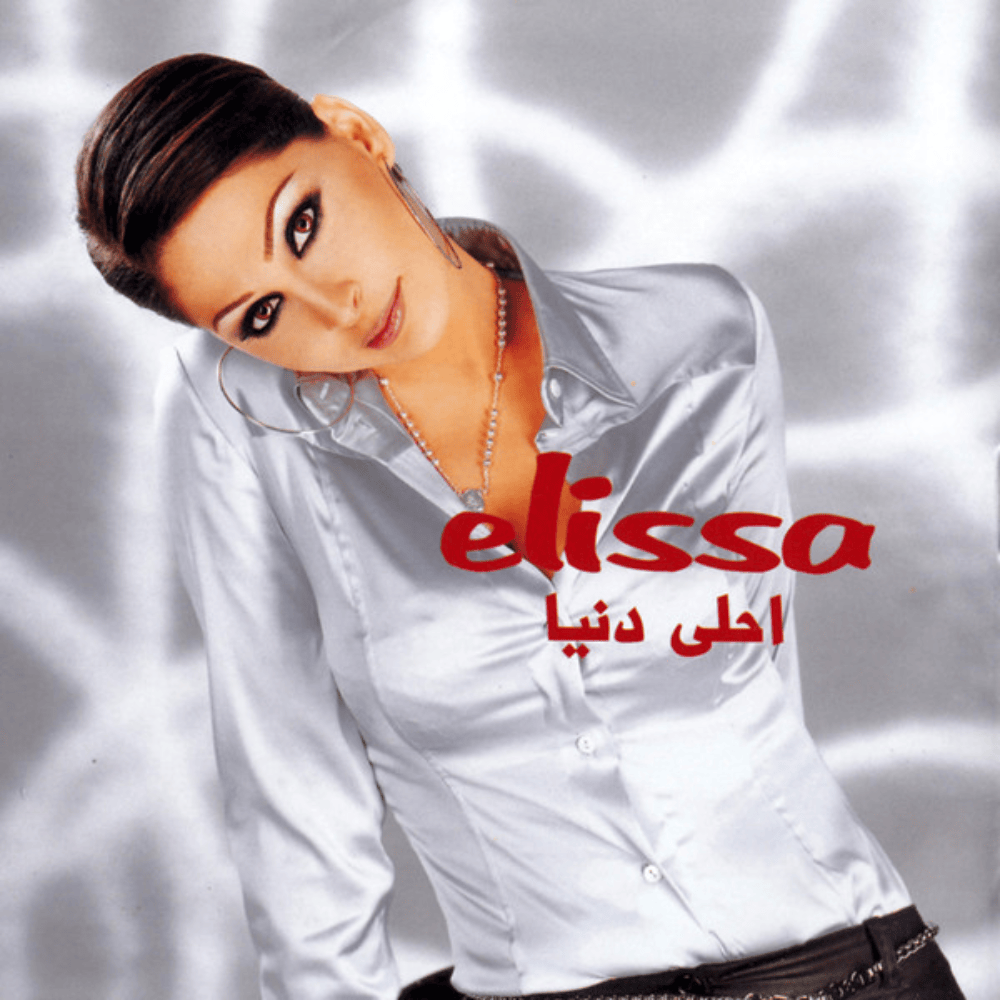

The following decade saw the rise of regional powerhouses who not only dominated the 90s but seamlessly reinvented themselves for the Y2K era and its futuristic sensibilities: Samira Said with Youm Wara Youm, Nawal El Zoghbi with Elly Etmannātoh, and Asala Nasri, whose 2003 Samsung commercial (Lawn Omri) used her voice, emanating from the device, the studio, and the screen, to announce the dawn of a new age in visual and sonic technology. And then there was Najwa Karam, who became the first artist to present seven songs within a single music video, pushing the boundaries of what Arab pop performance could look like. The early 2000s saw the rise of a new wave of divas such as Haifa Wehbe, Elissa, Nancy Ajram, and Ruby, whose careers blossomed with the emergence of satellite TV and music video channels, with their blend of overt sexuality, unapologetic glamor and emotional depths. Platforms like Melody, Mazika, ART, Nagham, and Dream didn’t just play music, they became prominent names and essential portals that shaped how pop culture was consumed and mythologized. These channels saturated the airwaves with polished visuals, catchy melodies, and femme fatales made for the screen, embedding them deeply into the queer imagination. Alongside them came a flashier, often controversial, cohort of ‘trashy pop’ starlets or as said in Arabic جيل الفن الهابط “lowbrow art generation” or “porno-clip stars”2; Marwa, Maria, Jeny, Nana, Najla, and others, who stirred public debates around sexuality, propriety, and Arab womanhood, only to disappear with the trends they helped ignite.

But what made these artists queer symbols in the first place? How did they contribute to shaping queer Arabic culture, both in terms of aesthetics and emotional resonance? How come the newer generations of Arab artists are severely challenged to replicate modern iconic status? What happened to the production of collective pop stardom rooted in Arab identity? And, more importantly, why are so many queer Arabs still emotionally anchored in a time capsule of the 90s and early 2000s? Why did this specific era of music videos become embedded in queer culture?

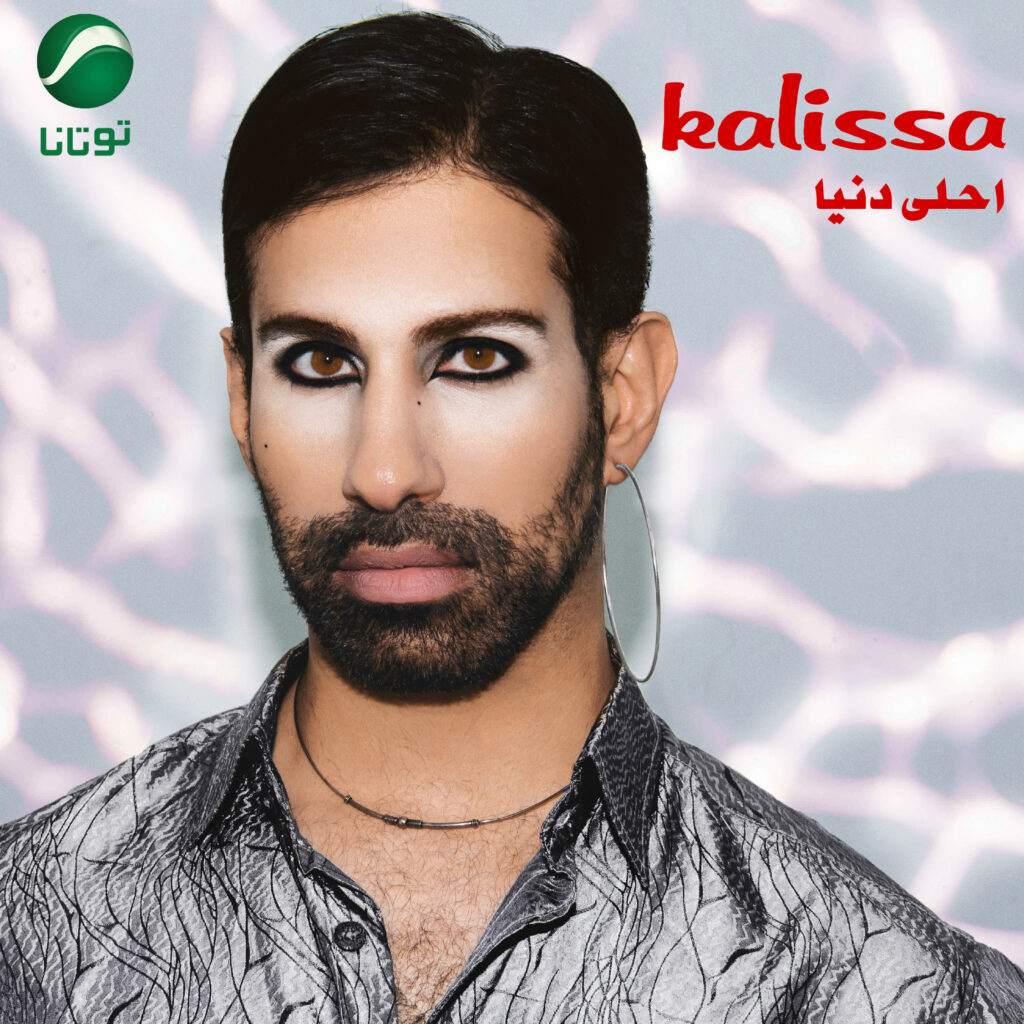

Clothing; Stylist’s own. Photographed by Zaid Allozi. Styled by Jad Toghuj. Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar. Cover design by Nawal Elzombie. Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi.

A Shared Fantasy – Divas and the Queer Imagination

For LGBT+ communities, divas have always been more than just performers, they are allegories of fantasy, resistance, and coded desire. In societies where queerness isn’t blunt or labeled, pop divas offer/ed a rare and powerful canvas for projection and exploration. Music videos, while not revolutionary in themselves, were deeply intertwined with broader social tensions, youth autonomy, shifting gender roles, and the individuals’ place within patriarchal constraints. They didn’t shatter the foundations of society or usher in democratic awakenings, but they did something equally vital: they became visual and emotional palettes through which sexuality, identity, and the body could be sketched, tested, and reimagined. Their allure lies in their contradictions, in the way they both conformed to and subverted norms, and as a result, they became sites of queer possibility and coded rebellion.

In this way, music videos became a clandestine form of queer expression. They gave queer youth more than escapism, they gave them a mirror in which to see possibility, a dreamscape where they could rehearse versions of self, and at times, a toolkit for emotional survival. The visual excess, the questionable lyrics, the glamor, the defiance, all became part of a queer lexicon, quietly passed between glances and rewinds, offering a world that, even if unreachable, was imaginatively real.

These women weren’t just consumed, they were internalized. They lived in bedroom posters, karaoke machines, fanzines and glossy magazines, pirated music videos, and television screens that unified entire households. They were accessible and aspirational. For LGBT+ audiences, the connection to these divas wasn’t only about glamour or fantasy, it was rooted in shared vulnerability. These women were publicly scrutinized for their sexual and gender expression, asked invasive questions about their personal lives, pressured to perform femininity within narrow limits, and expected to justify their desirability on regional/national television stations. In some cases, even their ability to be ‘good mothers’ was questioned. They were shamed for being too sensual, too independent, too bold. They cried on screen beneath the weight of public intrusion, speaking openly about marriages, divorces, plastic surgery and sometimes suicide. They were subjected to intrusive questions about their personal lives: “Why do you dress like that? Do you want to seduce the audience?”, “Do you think your success is because of your voice or your looks?”, “Why haven’t you married yet? What’s the problem?”, “Why did you get divorced? Did your husband cheat on you?”, “What cosmetic procedures have you had? List them for us,” “Do you think what you’re doing pleases God?”

In the 2002 program Sa’a Biqurb Al-Habib, Haifa Wehbe appeared crying under the pressure of journalist Tony Khalife after being asked about her daughter and the use of her sexuality, while Nawal Al Zoghbi faced a barrage of questions on the same show about cosmetic procedures and her appearance. These two interviews reveal the ongoing conflict between female artists’ personal lives, reflecting how repeated media intrusions into their private lives impose social and media pressures on women in the Arab entertainment industry. In many ways, they embodied the queer experience: seen as excessive, foreign, corrupting… Objects of both desire and disgust. In witnessing their dehumanization, queer viewers recognized their own. And in the cracks of those televised breakdowns, they found an unexpected kind of solidarity.

Their performances spoke the language of regional pop but carried undercurrents that queers instinctively understood: exaggeration, performance, and dramatic survival. In becoming such pervasive figures, they were also commodified, marketed and sold not just as entertainers but as ideals. For queer Arabs, this commodification was a double-edged sword: while it made the divas more visible and widely circulated, it also flattened their complexity. Yet, in that flattening, queer viewers found room to project, reshape, and reclaim. Therefore, what was crafted for the male gaze became, almost by accident, a palette for queer identification. For many LBT women, these icons also sparked early sexual awakenings, through their unapologetic sensuality, their command of the stage, and the intimacy they exuded, these artists helped many queer women recognize, name, or feel their own desire for the first time. What these women gave to queer Arabs wasn’t just entertainment, it was a language, tools, fantasies, and sometimes, the first glimpse of a world in which queerness could not only be imagined, but revered. Egyptian artist Ruby, for instance, was often vilified for her overt sensuality, but as critics themselves once noted: “If all it is about is catering to men’s vile instincts, what are the girls doing there?”, a reference to the many female fans dancing enthusiastically at her concerts3. Her wide female and queer fanbase complicates the idea that these performances were merely a commodity, they also touched queer women on a deeply personal level, becoming sites of sexual awakening as much as pop spectacle .

Video clips, endlessly broadcast on Arab channels, created fantasies of becoming “what one could never be” ideals presumed to be socially unacceptable. As Palestinian poet Tamim Barghouti observed, “Instead of forming and reforming identity and imagination, and redefining what beauty means, the music and video clips on Arab channels make Arab youth want to become what they can never be, and make them want to become an image of their colonial masters.”4 For queer youth in particular, living through these videos, with their exaggerated gender performances and heightened sensuality, became a kind of queer language. They offered a shared emotional and visual vocabulary, translating desire, gender, and rebellion into images instantly recognizable across the region.

These pop divas did not simply symbolize femininity; they embodied a Westernized, aspirational image, glamorized, sexual, and echoing colonial aesthetics. It means that when pop stars in the region are presented with Westernized features, hyper-feminine aesthetics, and associations with luxury and consumerism, this signals an adoption of beauty standards shaped by a history of cultural and media colonialism. In other words, the “desired beauty” becomes conditioned by traits that are not local, but imported through Western dominance over image, identity, and public taste. This created a layered imaginative identity: to desire them, to become them, or even to parody them, often all at once. Their appeal lay precisely in this contradiction, simultaneously an act of identification, imitation, and resistance. The diva became a complex figure through which queer individuals could process their own desires and perform gender in ways that defied rigid societal norms.However, this queer and regionally nuanced engagement is often flattened in Western interpretations. As Charles Paul Freund notes in “Look Who’s Rocking the Casbah,”5: “The Arab world will eventually achieve its long-delayed goal of liberalized modernity; it might just as well dance itself there.”6 While the Arab world might appear to be dancing its way toward liberal modernity, such a reading ignores the subversive, ironic, and emotionally charged uses of pop culture within the region. What is lived as a queer, coded form of resistance is too easily framed by outsiders as a sign of “progress” or “catching up” with Western ideals. This colonial gaze strips the images of their contradictions and complexities, turning hyper-femininity and queer performance into exotic spectacle, fetishized rather than understood. In trying to deconstruct the West’s dominance, we risk being reabsorbed into its narrative.

Clothing; Stylist’s own. Photographed by Zaid Allozi. Styled by Jad Toghuj. Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar. Cover design by Nawal Elzombie. Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi.

Desire, Censorship, and the Language of the Music Video

Anyone who lived through the Arab world in the 2000s would remember the moral panic and widespread anxiety that surrounded satellite music channels and pop divas, as reflected in headlines such as “The Music Video… A Virus Destroying Societies!!”7, “The Music Video and the Moral Threat”8, and “The Discourse of the Body in the Arab Music Video.”9 Critics in Arab media condemned these videos as moral threats, excessively sexualized influences, and corrupting forces that posed a danger to traditions, marriage, and public morals. These videos were seen as corrupting for youth and undermining parental authority, as Osama Shahadeh explains in his article for Al-Ghad, “The Crime of the Music Video Against Our Societies”:“The music video has become one of the most powerful tools that keep Muslim society, with its youth and young women, in a state closer to sedation, and far from vigilance regarding the issues of the nation…”10

But queer audiences saw something else. These clips weren’t agents of social ruin, they were rare sites of layered possibility. While it’s true, as Arab cultural critics such as Lila Abu-Lughod have observed back in 1997, that TV didn’t dismantle patriarchal hierarchies, they did expose deep anxieties around youth, sexuality, and modernity. “Television is an extraordinary technology for breaching boundaries and intensifying and multiplying encounters among lifeworlds, sensibilities, and ideas… Even if it ultimately helps create something of a ‘national habitus,’ its real importance lies in how television provides material which is then inserted into, interpreted with, and mixed up with local discourses and meaning systems.”11 In that contested terrain, queer Arabs found a space they could quietly occupy and transform. The spectacle became subtext. The glossy visuals and melodramatic lyrics became vessels for desire, experimentation, and emotional archive.

The rise of the Arab pop diva coincided with a media infrastructure that made them omnipresent. In the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s, television became a single shared stage. Access to Arab pop culture was more or less universal, whether you were in a village in southern Morocco, the outskirts of Cairo, or a high-rise in Amman. Satellite channels like LBC, MBC, and Rotana democratized celebrity through shows such as Studio El Fan, Ya Leil Ya Ein, Top 10, Pepsi Musica, Star Academy, and Ramadan variety specials, all of which brought the same stars into homes across the Arab world. This collective media consumption produced a powerful cultural memory. Everyone knew Ruby’s “Leih Beydary Keda,” Haifa’s “Boos El Wawa” and Elissa’s “Ayshalak.”, along with the debates they ignited. These weren’t just pop songs; they were time stamps. They played at weddings, blared from car radios in city streets and public transport, and flickered across television screens during family gatherings, and in gay house parties where they were lip-synched like gospel.

I remember when the sister of one of my closest friends at the time was preparing for her wedding and the family began drafting the list of songs the DJ would play. Ruby was at the height of her popularity then. But his mother firmly insisted that no Ruby songs were allowed, fearing that “the girls might dance like Ruby” at the wedding. That moment, simple as it was, captured the tension these divas provoked: between a desire for release and the pressures of social policing.

The debate even spilled into sacred spaces like mosques; and paradoxically, imams would mention these singers by name during Friday sermons, warning that they might “corrupt” the youth or “distract” society. I grew up hearing the voices of preachers echo through the loudspeakers, invoking Haifa, Nancy, or Elissa as if they were forces capable of shaping the destiny of an entire generation. In this way, these songs shifted from mere entertainment to moral battlegrounds where collective anxieties and conservative imagination played out.

The diva became a cultural symbol and a private obsession, where the sacred, the public, and the personal intersected, and where the language of pleasure, dance, and fantasy became part of the debates that shaped the memory of an entire generation.

Clothing; Stylist’s own. Photographed by Zaid Allozi. Styled by Jad Toghuj. Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar. Cover design by Nawal Elzombie. Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi.

The dispersal of pop culture in the age of social media

As Y2K aesthetics and 2000s nostalgia reach peak relevance in the 2020s, revisiting that era underscores how dramatically the making of cultural icons has shifted. The machinery that once produced Arab divas, rooted in television, music videos, and tightly controlled media narratives, no longer operates the same way. Television no longer commands mass attention, at least not to the same extent. In its place, social media, with its algorithm-driven fragmentation, has taken over. But this new digital terrain hasn’t given rise to new divas; instead, it has given us influencers. “Social media creates stars within its own sphere, but it doesn’t produce lasting fame. A star may be born on social media, only to fade away as soon as another one appears,”12 Nawal El Zoughbi once remarked in an interview.

While artists like Elyanna and Saint Levant have emerged as globally palatable faces of “Arab pop,” their appeal is often curated through a Western lens. Their aesthetics and soundscapes lean into familiar Orientalist tropes: Elyanna dances in flowing robes and daggers against desert backdrops, while Saint Levant delivers trilingual bars designed more to intrigue Western ears than to speak to regional ones. Both artists grew up in the diaspora, and their work, while Arab in tone, is largely produced for and consumed within diasporic and alternative circles. Their “Arabness” is stylized, exported, and, at times, commodified. This is especially clear in how both position themselves in the global media landscape, where “Palestine” becomes part of the brand, an aesthetic, a symbol, a cause to market, rather than a complex lived reality. Yet this tendency toward self-Orientalism isn’t new. Earlier commercial pop figures like Myriam Fares and Saad Lamjarred, both similarly leaned into hyper-stylized, exoticized performances that played into both regional and Western expectations of “Arabness.” Shakira, despite having no lived connection to the Arab world, capitalized on her Lebanese heritage through belly dancing, larger than life Cobras and Middle Eastern motifs, crafting a global brand rooted in symbolic Arabness. The key difference is that while artists like Myriam and Saad, despite their problematic artistic directions, operated within a regional commercial system that embraced spectacle for mass appeal, today’s global-facing artists navigate a hybrid space, performing identity across audiences. The result is a more self-aware, curated Arab pop, one that often blurs authenticity with aesthetic strategy, and heritage with brand currency.

The Arab speaking region today lacks the centralized infrastructure that once supported the rise of commercial pop stars with deep regional impact. While social media and the internet have democratized access to production and visibility, they’ve also fragmented audiences and made sustained regional stardom more elusive. This shift is compounded by state censorship, economic precarity, and political repression, all of which inhibit the production of joyful, glamorous, or subversive pop culture. What we’re left with is a scattered archive, vibrant, experimental, often underground, but rarely unified.

Today, the Arabic-speaking region lacks the centralized infrastructure that once enabled the rise of commercial pop stars with wide regional reach. While social media has democratized visibility, it has also fragmented audiences, making sustained stardom more elusive. The collapse of that earlier pop ecosystem is not just a byproduct of digital disruption, it reflects the withdrawal of political and economic forces (notably Gulf capital) that once used pop culture as a soft-power tool to project liberalized modernity. In other words, the infrastructure may have vanished because it fulfilled its ideological role, or because its usefulness expired. Now, under intensifying censorship, economic precarity, and authoritarianism, what remains is a vibrant but scattered archive: experimental, often underground, and rarely unified. Its fragmentation mirrors the political disintegration of the region itself, and perhaps, resists the very spectacle it once tried to emulate.

Clothing; Stylist’s own. Photographed by Zaid Allozi. Styled by Jad Toghuj. Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar. Cover design by Nawal Elzombie. Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi.

Archiving Desire – Queer Nostalgia and Digital Reclamation

Faced with a lack of new icons who embody both pop star glamor and cultural rootedness, the queer Arab community continues to look backwards. The nostalgia for 90s and 2000s divas is more than just sentimentality, it’s a longing for an era when Arab pop culture felt like ours. It was a time when Arab identity wasn’t a curated filter for a Western audience, but a lived, regional truth, when stars sang in Arabic dialects, wore designs by Arab fashion houses, and performed on Arab stages for Arab audiences.

The current generation of queer Arabs is one that came of age online, shaped by global queer culture, yet still emotionally tethered to the icons of the past, artists whose influence may not have seemed radical at the time, but whose work resonates powerfully today. In many ways, we are witnessing the extension of their legacy, or perhaps the long-delayed fruition of their cultural labor. Drag performances at queer Arab parties often pay tribute to the very artists mentioned in this article. Aesthetics lifted from Sherihan’s theatrical wardrobe or Nawal El Zoghbi’s meticulously crafted music videos are now woven into the fabric of queer self-expression. These divas have become more than pop stars; they are living cultural archives, repositories of an Arab identity that is glamorous, complex, and deeply queer-coded.

Digital media pages like Trashy Files, Takweer, KHAIFA, and The Mixtape Shop, while all different and diverse in content and style, they exemplify this shift: they draw on shared nostalgia not simply to build an audience, but also to archive a shared cultural past and memory. As Marwan Kaabour, founder of Takweer, notes, “Nostalgia is a tricky seductress… My hope is for people following the page to use these archival entries as starting points to make a better understanding of today, rather than fixate on them as end points.”13

These platforms show how digital fragmentation can become a tool for community-building and cultural preservation, while also challenging the assumptions of what constitutes legacy, taste, and value. They don’t just collect memories, they recontextualize them. In Kaabour’s words, the criteria for Takweer is not only about explicitly queer figures, but also about “stories that challenge normative societal norms at large,” always infused with “a healthy dose of humour and camp.”14 By reclaiming pop culture moments once dismissed as frivolous or morally corrupt, they invite critical re-readings that are both camp and political. In doing so, they allow queer audiences, who were once passive consumers of culture, to become active curators of it. And although the current queer generation did not live through those queer moments at the time, nor take part in shaping their language, they are now part of the continuity of this archive; preserving it, carrying it forward, and passing it on. As if the years 2003 and 2007 are no longer dates from the past, but moments reclaimed and lived anew in the present.

These pages function as digital living rooms or memory vaults, spaces where scattered experiences of queer Arab youth can converge. Through subtitled clips, memes, archival footage, and editorial commentary, they transform nostalgia into a political act, preserving the ephemeral and elevating the disposable. They resist erasure not by shouting, but by circulating, editing, repurposing, and resharing. Most importantly, they propose an alternative canon, one that centers emotion, contradiction, and play. These platforms aren’t just preserving a lost pop era; they’re building a new kind of cultural legitimacy, one rooted in queer memory, affect, and humor.

Clothing; Stylist’s own. Photographed by Zaid Allozi. Styled by Jad Toghuj. Makeup and Hair by Samara Qamar. Cover design by Nawal Elzombie. Creative direction by Khalid Abdel-Hadi.

A Fragmented Pop Legacy and a Lost Cultural Language… What Remains of the Diva?

These divas once belonged to a shared public imagination, but that sense of cultural unity has since faded. Regional pop is no longer the lingua franca it once was: algorithms have replaced shared longing, and virality has overtaken artistry. In place of the over-the-top Arab diva, we now have niche influencers, global icons, or sanitized celebrities molded for Gulf markets. The conditions that once gave birth to a Nancy Ajram or an Aline Khalaf no longer exist; without unified media platforms, and amid rising repression and economic instability, the creation of new regional icons feels almost impossible. For queer audiences, this loss is even more acute. These women weren’t just part of our youth, they shaped how we imagined ourselves. In their glitter, extravagance, and contradictions, we glimpsed our queerness before we had language for it. Today, in a fragmented cultural landscape, that shared fantasy feels endangered, not just by time, but by a collective memory that no longer invests in the diva as icon or mirror.

And yet, there is hope. The continued veneration of 80s, 90s and 2000s divas speaks to a hunger, for authenticity, for cultural specificity, for shared experience. Perhaps the path forward isn’t to look for the next Haifa, but to ask: what would an Arab diva look like today, in this fractured reality? What stories would she tell? What language would she sing in? And how might she speak to the queer Arab community, and not through nostalgia, but through radical presence? Perhaps the answer lies in holding both truths: cherishing the past while imagining a more inclusive, expansive future. And at the same time, benefiting from a decentralized media structure, publishing through Instagram, Tiktok, X (formerly known as twitter) threads, and online platforms, that, despite its fragmentation, offers emerging and marginalized artists new avenues to create, connect, and be seen.

While this nostalgia affirms a deep emotional bond with the past, it also creates space for queer reinterpretation. Through parody, performance, and tribute, queer artists reclaim these divas, once shaped by the heterosexual gaze, and transform them into icons of camp, resilience, and queer empowerment. Drag artist Anya Kneez channels Haifa Wehbe’s glamour as a recurring motif in her performances; Mous Bahri pays tribute to Ruby through digital performance; Shayma alQueer offers playful homages to Tunisian “trashy” pop and its distinct sense of humor; Salma Zahore reimagines Warda through a vogue-inspired lens; and Khansa revives Samira Tawfeeq and Najah Salam in his live shows. In re-performing these icons, queer artists turn mainstream femininity into a site of joy, memory, and resistance. Until then, the bejwelled mic of Haifa, the sad tragic beauty of Elissa, and the relatable power of Ruby, all remain unmatched, etched in the collective queer memory, not as ghosts of the past, but as lighthouses in a cultural landscape adrift.

Designer’s reflections

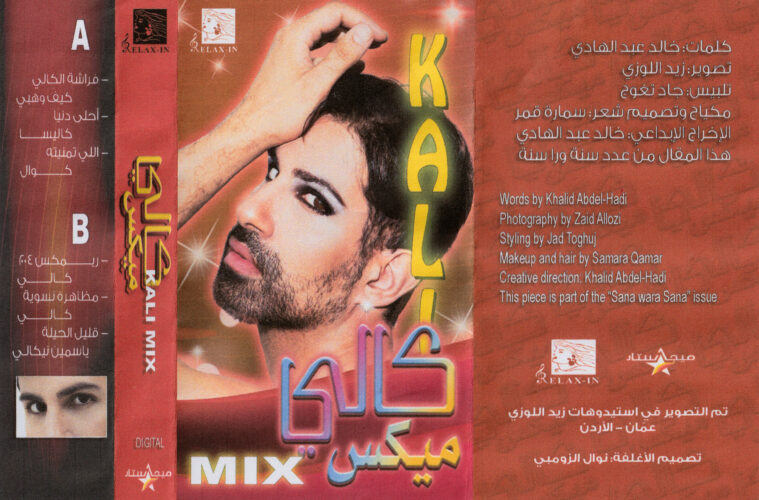

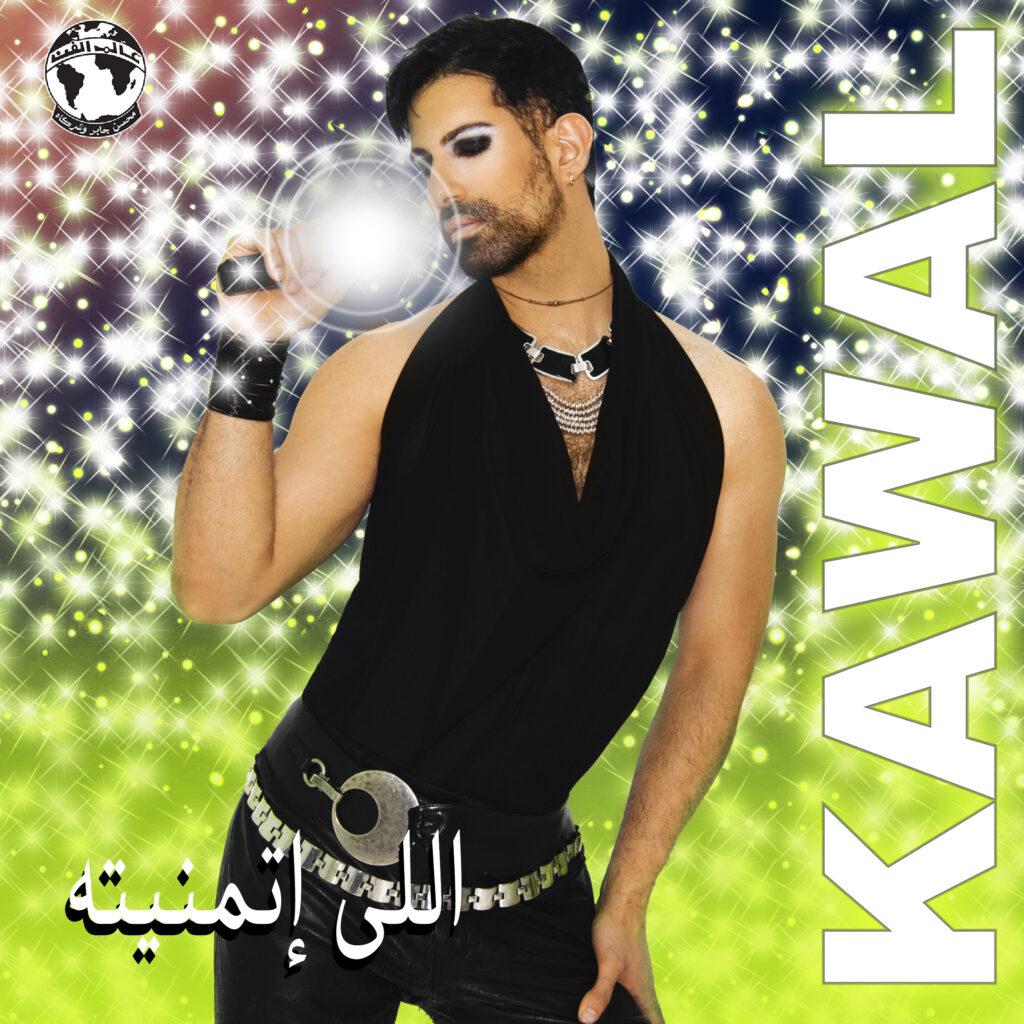

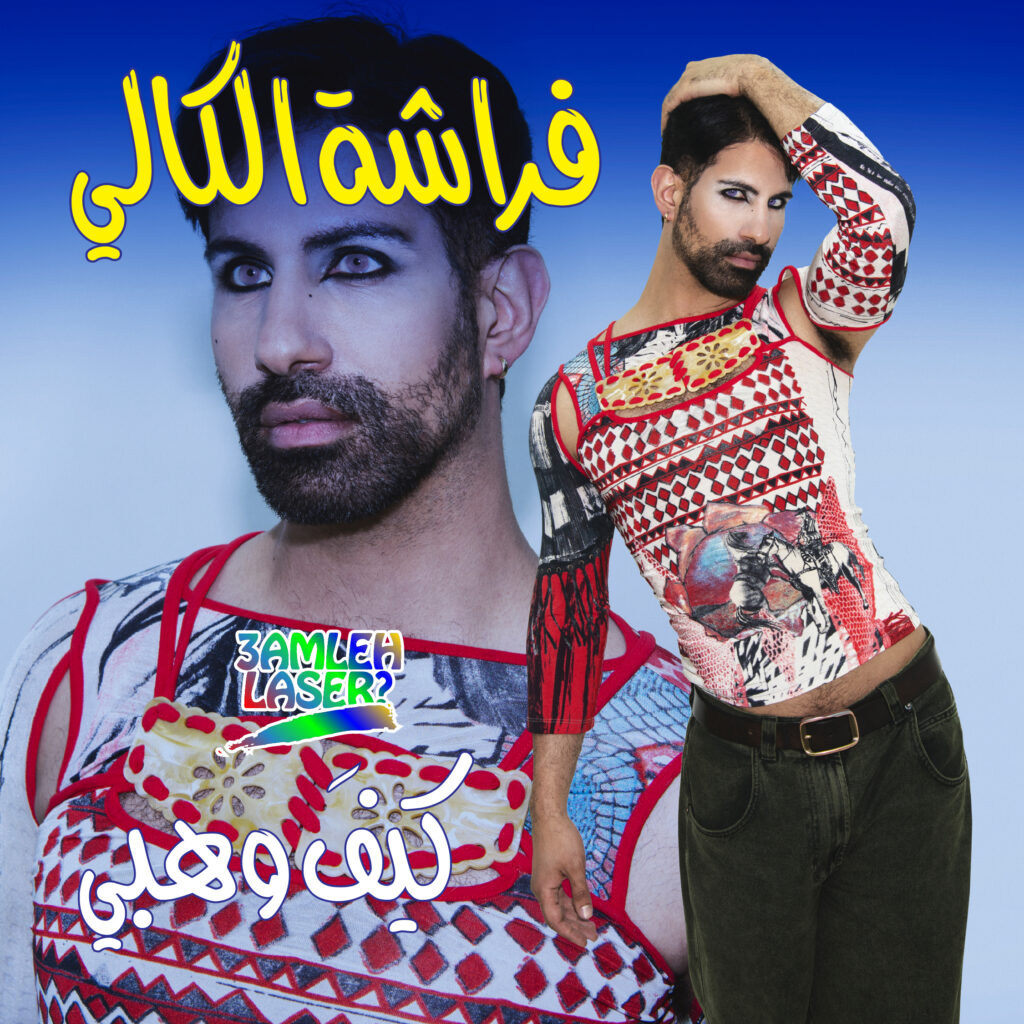

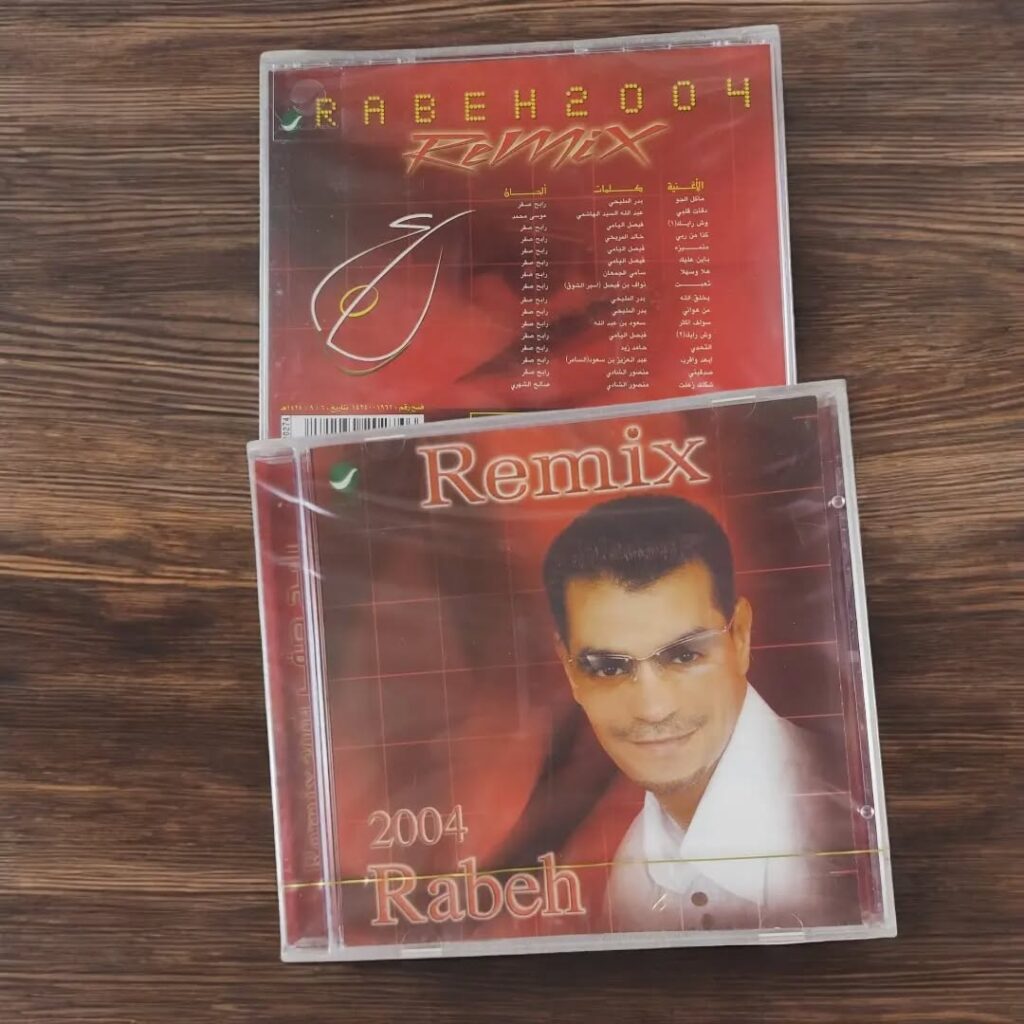

When I learned about My Kali’s piece and photoshoot project, I immediately felt like I needed to answer a call from a young 15-year old gay boy holing up in his parents basement making fan art, imaginary album covers and websites of female Arab pop stars on his Microsoft Powerpoint and CorelDraw. I remember vividly the rush of going to Firas records (تسجيلات فراس) in Jabal Al Hussein after school to flick through cassettes and CDs in absolute awe of these pop beasts with blurred lines about which is original and which is a bootleg, because frankly it didn’t matter، what mattered was always the music.

This ‘task’ felt immediate, natural and a little opportunity for my own graphic designer self to unlearn years of calcified cynicism that tamed my child-like wonder; I felt the jolt back of rabid fandom of these Arab pop girls.

The album covers visuals created directly reference a number of albums by Elissa, Nawal (not me, the real one from Byblos), Haifa as well as Shams and Rabeh. I suddenly found myself able to swiftly decode the logic of these designs; I knew the fonts, the backgrounds, the brushes, the gradients and all the effects; as if I never left that loud beige PC tower computer.

The designs-or responses-were made with a heart that loves and reveres these world makers of Arab pop stars; music so good that visuals were a supporting act, and it felt like its time for us to question how much are we nowadays “celebrating” or ridiculing our very own makers and markers of culture only to lazily throw it under cloaks of kitsch and low-brow acts. Our Y2K, not the American Y2K, was the time of beauty; beauty of being liberated from shackles of a hyper visual economy and the beauty of the music taking centre stage.

I hope you get to feel the same rush I felt as I raced my way after school to grab a CD (with 3 days worth of lunch money) to get home, play and escape a little to the worlds built by these glam creatures.

- Women rock the casbah – CSMonitor.com

- What Would Sayyid Qutb Say? Some Reflections on Video Clips – Arab Media & Society

- Video Venom Must Stop!, 2005

- What Would Sayyid Qutb Say? Some Reflections on Video Clips – Arab Media & Society

- Look Who’s Rocking the Casbah – Reason.com

- By quoting Freund, I’m not aligning with his view, but rather exposing how these very aesthetics, Arab pop divas, hyper-femininity, music videos, queered performances, are misread or fetishized by the same West we’re trying to deconstruct.

- Al-Jazeera Newspaper, “The Music Video… A Virus Destroying Societies!!,” September 9, 2004.

- Al-Ahram Weekly, “The Music Video and the Moral Threat,” Cairo, 2004.

- Mohamed Ghoneima, “The Discourse of the Body in the Arab Music Video,” Journal of Arts and Media, University of Misrata, Libya.

- Osama Shahadeh, “The Crime of the Music Video Against Our Societies,” Al-Ghad, Issue 581562.

- The Interpretation of Culture(s) After Television – Lila Abu-Lughod – The article, while slightly dated (published in 1997), provides a lengthy insight into the changing field of anthropology as a new form of media/medium, the television, arrives. The author’s main intent is to illustrate how the face of anthropology is changing in the wake of new media forms, what challenges the field now faces, as well as how approaches can be modified to “fit mass-mediated lives” (Abu-Lughod 2).

- نوال الزغبي: الرجل يغار من المرأة الجميلة | Laha Magazine

- Exclusive quote provided to the author by Marwan Kaabour, August 2025.

- Exclusive quote provided to the author by Marwan Kaabour, August 2025.