Words by Imène Amara

Translated by Hiba Moustafa

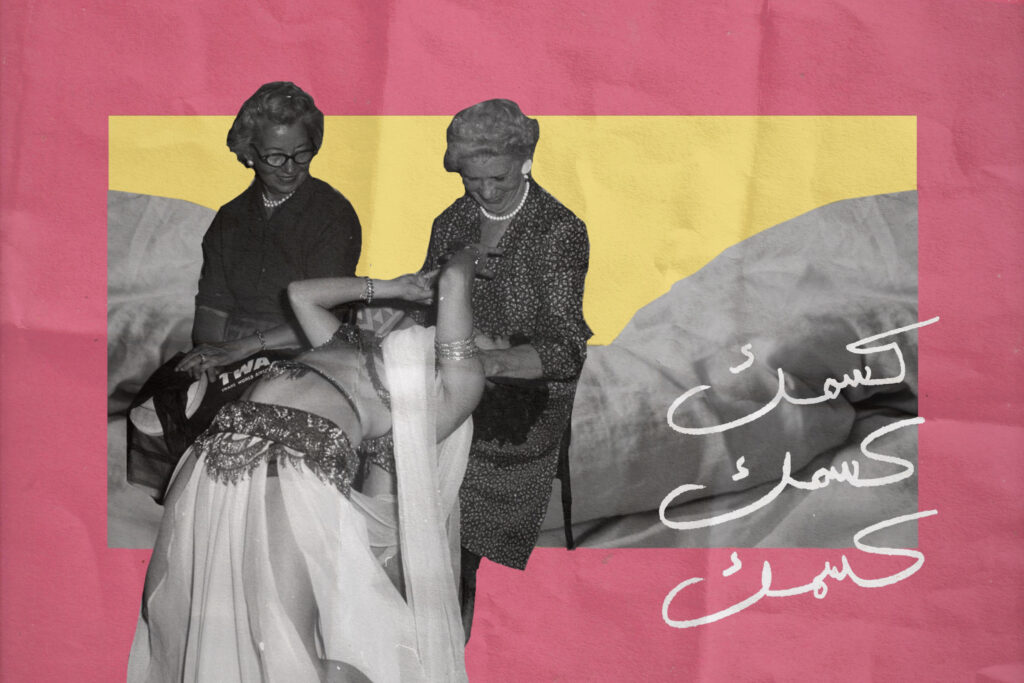

Illustrations by Lina A

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

I dance to seduce men … I am fully aware of how they think of me, and of my body when I sway flirtatiously and seductively before their eyes. I know that, in these intimate moments, they imagine having and touching my body and its curves. Why should I lie? This is the truth that I have faced several times; it doesn’t offend me and I don’t feel ashamed about it.

When the idea of writing about belly dance, in particular, came to my mind, I checked a variety of populist, feminist, nationalist, conservative, artistic, aesthetic, and erotic clips and commentaries that compared, analyzed, prohibited, evaluated, cheered for, and condemned belly dance. Supporters, fans, and defenders have always been desperate to prove that belly dance isn’t sexually provocative, as is rumored or practiced by some “depraved” dancers. This tension between critics and supporters of belly dancing is evident in the fact that even Taheyya Kariokka wasn’t celebrated until after Edward Said praised her leftism and activism. She was seen as also nobler than her peers, transcending the mere act of dance and pairing it with a more socially respectable act; Said wrote that Kariokka didn’t resort to provocative light nudity nor “bobbed her breasts.”1

There are always two categories of women: the Madonna and the Whore, and men, whoever they are, seem to have the right to put us under either category they deem fit. For most people, belly dance has negative connotations, including moral stigmatization and cultural contempt, because it is highly correlated with women’s bodies, and therefore, with seduction and sex. It’s undeniable that belly dance as a practice has always been associated with men’s pleasure, either through watching or sexually possessing the bodies of female dancers. However, can we really reduce the issue to the binary of male spectator/gaze and female coerced sexual objects? Do we not re-use the same patriarchal logic that denies women the desire to dance as a practice or to want and even enjoy it as a seductive tool? Maybe we can better understand it by comparing it to other two practices that are equally complex to address: sex and pornography.

Why should it be a problem if belly dance or anything else is sexually provocative?

Feminism and Respectability

Having engaged with the feminist scene in the region for years, I admit that our bodies – as people who identify as women – are still a domain for daily conflicts, taboos, negotiations, and wars, which we can use as we wish. Concepts like sexual pleasure, sexuality, nudity, polyamory, casual and open relationships, exposing our bodies, and posting our photos and videos are still controversial among feminists themselves. There is always a group demanding us to fit into an ideal and perfect image so as not to discredit various causes, and to cancel the “scandalous” personal from our public lives so as not to lose our legitimacy (for having sex, for example). We didn’t forget how Puritan and Muslim feminists abandoned Rahaf Qanun, for example, when it became known that she had a rich sexual life before and after fleeing the KSA, and we did not forget how many feminists failed to support the TikTok girls and went along with the Egyptian regime in accusing them of violating values and morals.

Others demand us to disdain our bodies and to maintain a “respectable” appearance so that our rhetoric has value and weight, for no one will care about what a feminist who wears revealing clothes or shakes her hips, dances, sways, and posts her dance moves for men to see. Those feminists demand us not to use curse words, especially “cunt,” even when they are directed at Zionists, for we must respect their mothers as fellow women. Conservative feminists in the region don’t adopt an exclusively Islamic frame of reference; they go beyond it to an Americanized puritanism that opposes all forms of “moral decay” and “transcends” bodily desires, and that stands against trans women, sex workers, and everyone who takes the female body out of dark rooms and traditional frameworks of meaningful monogamous relationships.

Commonly-held rules in this ideology include: You are superior to men. You only have sex for love and with just one man. You don’t watch porn or pant after random practices. You aren’t into sadomasochism. You don’t accept a dowry when you marry. You don’t sell your body or seduce men with your charms. You’re precious and only a worthy man will have you. Don’t fall into the trap of patriarchy. Memorize what we are taught to be as a woman and do the exact opposite in order to be a true rebellious feminist.

My relationship with my body, my desires and preferences, and sex has always been very complex due to my upbringing in a highly conservative and self-absorbed society, and I haven’t had many opportunities for sensory experiences and self- or collective exploration. Feminism added to this complexity, at least initially. It made me wonder whether I have the right to use my body as a seduction tool. Is this not the role expected of me as a woman as dictated by patriarchy? Isn’t it also my right to follow my sexual desires and, one way or another, challenge this same system that is trying to curb and mold my sexuality? What will we do with all these women who want to dance? Should we stop them? Look down on what they do? Exclude them? Is this again the only form of custodial feminism? Should we be ashamed of being women, hide our desires, and deny our sexuality on the pretext that it’s compatible with the role assigned to us by patriarchy? What would be the next step if we followed this logic without investigation? Should we stop women from having children since motherhood is the most prominent role that is imposed on us and confining us? Should we insist that all women are necessarily oppressed within heterosexual relationships and incapable of manipulating and exploiting power dynamics within them to their advantage?

Illustration by Lina A

Back to Belly Dancing

Back to belly dancing. I don’t wish to talk about it as a form of art or examine its history or symbolism, nor its connection to religious rites in ancient times or its gradual marginalization later. I’m not a specialized researcher and there are numerous volumes and documentaries on the subject. I want to talk about it as a normal woman, one among hundreds of thousands who dance before mirrors, at weddings and in events, and those who dance before their smartphone cameras or for their intimate partners.

Belly dance has fascinated me from early on, with its sensual aspect that I unconsciously felt as a child. I only knew that belly dancers were semi-naked women, who performed in ways that impressed and enchanted men in nightclubs. I wanted to be like them, to possess this obscure power of seduction and body magic. I grew up in a milieu where belly dance was viewed as something “filthy,” unlike our Algerian traditional dance that was refined to fit the new nation that preserves its Arabism and religiosity. I danced before my mirror, I danced alone in my room, and I danced in front of my female relatives in festive gatherings, where men are always absent, but I used to imagine that I had a male audience. Years went by before I danced for a man, then I danced before other men in public places.

I dance for my pleasure and that of others. It’s a pure sensual pleasure that I feel when I lay naked on the beach. It’s the pleasure of the exposed body that is freed from the constraints of clothes and middle-class morals that stifled it to preserve it from men’s gaze and getting a tan. Belly dance is exciting, and the source of this excitement is the movement, dance clothes, and being seen. When I dance, I watch myself through others’ eyes and through my own imagination as well. These images mix with the ones emanating from my memory, pictures of the golden age dancers. I become one with them and their seduction to mine. I surrender to the magic of Samia Gamal’s moves, get inspired by Taheyya Kariokka’s attractiveness, and invoke Soheir Zaki’s spirit. They keep my company as goddesses of seduction and flirtation.

Dance within an intimate context adds a different kind of excitement to the body: the excitement of the other party and of thinking about what will happen after a dance between two bodies. This excitement fills the dancer too, even before the spectator; it isn’t a tool to create it for others. Gilles Boëtsch and Dorothée Guilhem define seduction as “rituals to attract another” that range from performance, dynamic self-performance to sensual and theatrical performance.2 This definition also applies to belly dance, for it isn’t mere artistic and expressive steps and movements, such as ballet or folklore dance.

Belly dance is playful and seductive, going beyond expression using the body to letting it express its emotions and feelings to the rhythm and meanings of music as well. There are happy, sad, and lustful songs in words and tunes – as seen in this scene from The Belly Dancer and the Drummer, Arabic الراقصة والطبال – and there are songs of longing and anguish. Maybe this is why I only dance for those who share my cultural background, for my seduction will definitely be lacking if the others didn’t understand why I chose “As Sweet As Honey” or “If It Were up To My Heart,” depending on the context, or if they missed that I was “The Sultan’s Daughter” who holds the water and they are the thirsty ones.

The centrality and subjectivity of the body in belly dance are described by Ezzat El Kamhawy as “The body’s real presence in all its luxury.”3 Waltz has fixed and definite steps that require training the body to repressed, mechanical, and monotonous commitment. Belly dance, on the other hand, provides a larger space for expressing the self, personal, and mood. It allows the body to flourish into its curves without the need to suppress or hide them, leaving them completely free to vibrate, appear, and dance on their own or with the rest of the body without affectation or artificiality. I dance to defy taboos and overcome restrictions. I dance so that my body turns into a middle finger raised in the face of my conservative upbringing that fears people’s talk and their daughter getting out of control.

Personally, I don’t like dance trainings that turn belly dance into calculated, repetitive movements. Nor do I like the foreign dancers who possess amazing athletic flexibility that doesn’t make up for their lack of musical sense and insensitivity to belly dance as a purely sensual pleasure, and as an extension of our culture and its perceptions of women, the body, and sex. How can a woman who is not accustomed to fully covering her body in public feel the secret pleasure that is mixed with fear and excitement that accompanies my appearance in revealing clothes before everyone dances and sways?

Practices of Seduction

I dance, then, to seduce men. Seduction is my authority, my power, my weapon of negotiation and resistance. In Erotic Capital: The Power of Attraction in the Boardroom and the Bedroom (2011), Catherine Hakim argues that seduction is a form of capital that patriarchy tries to control because men cannot monopolize it. Patriarchal societies raise those who identify as women to hide and ignore this resource under old labels, such as eib and haram, or new ones like “girl bosses” who manages to assume the role of traditional men to the fullest, forbidding herself from falling into love. Some feminists fall into the trap, too, opposing all manifestations of the body and heterosexuality as they ultimately serve the interests of men who enjoy seeing and using our bodies; we shouldn’t give this to them even if it means that we live as nuns. This morally strict position ignores power dynamics within heterosexual binary stereotypes, in particular, with all their spectrums and variations. For, in spite of patriarchal relationship stereotypes, there are always exceptions and positions – both fixed or changing – and struggles that are not necessarily violent, which are reflected particularly and intensively in sexual relationships and similar erotic practices.

The seduction game is definitely one of these. We have all inherited the stories of mothers, grandmothers, and aunts, who got what they wanted from their husbands, using their power of seduction of “pillow talk” or sexual extortion, or through exchanging a Thursday night’s dance for a privilege or present. Fighting the system hasn’t always taken the form of revolutions and open rebellions; negotiation has been women’s weapon for survival. Analyzing the manifestations of seduction as a power, be it a power of influence, resistance, identification with prevailing and imposed conditions, or liberation, is a necessary entry point for a feminism of the body and everything related to it including dance, sex, or pornography. We must have this discussion one day, even if we don’t get a unified answer.

Why should we restrict women to the role of being passive receivers of men’s seduction? Why should we always portray them as submissive victims when they actually aren’t? Even in the most limiting relationships, where men control and influence all aspects of life, there is an outlet and margin for gaining some influence. Seduction is in itself a kind of power that needs a margin of freedom to practice, and not just to abstain from, even if the relationship is originally non-consensual in terms of the concept of clear and explicit Western consent that does not apply to our context, where girls still marry without getting to know the groom and where their consent is secondary to that of the father and family. Even in this context, women engage in the game of seduction from a feminist point of view that does not ignore power dynamics, but redefines it and understands its different contexts, some of which are not always fixed.

How can we re-examine belly dance from a feminist perspective? How can a practice that is so closely attached to gender stereotyping be a tool for liberation, emancipation, and rebellion too? How should we, as feminists, dismantle the stigma and shame surrounding our bodies, sexuality, eroticism, and seduction?