Words by Sophia Shalabi

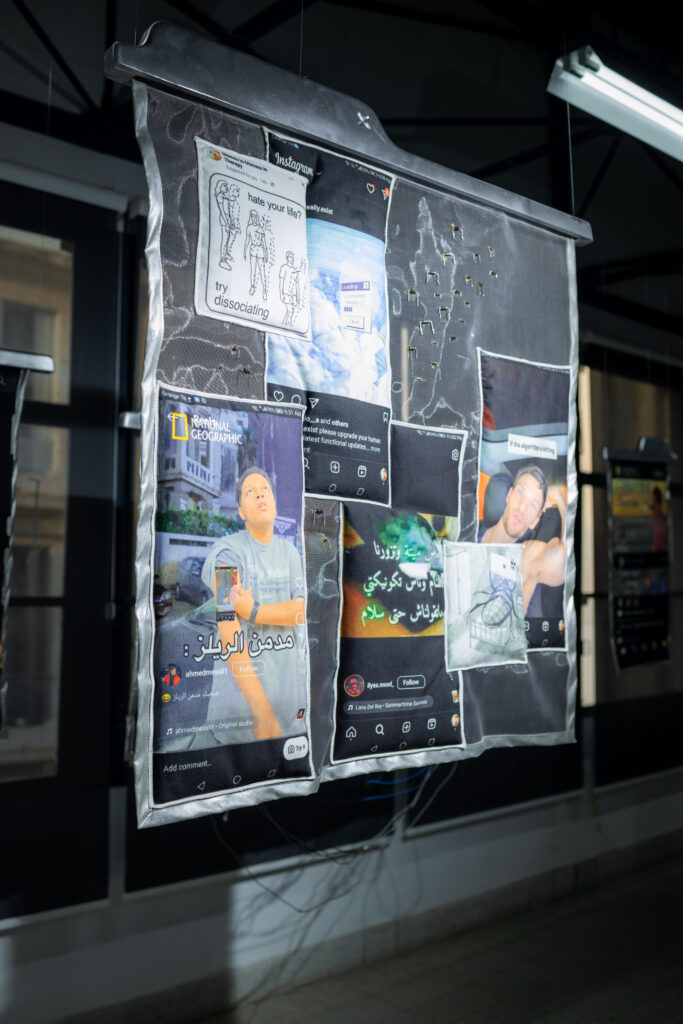

Featured Art Project: “DESENSITIZING CONSENT” by Dhia Dhibi

Photography by Nizar Messaoudi – Exhibition at Le 32Bis in Tunis

This piece is a supplement within the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Art project ‘DESENSITIZING CONSENT’ asks:

How does constant exposure to online imagery of war, violence, and brutality affect our perception and emotional response? It explores how endless scrolling through digital landscapes saturated with extreme content produces a numbing effect, an effect amplified today by the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

*This article was written December 2024, and its sentiments continue to resonate.

While visiting my Sitti, we gather in the family room to watch news around the television. Following her nightly ritual, the weather forecast and mind-numbing distractions of celebrity drama or local sports become punctuated with imperialist propaganda about the “Israeli-Hamas war.” Shifting between subdued sullenness and rage, she whispers prayers for her Palestinian kin living under Occupation and Genocide. She immigrated to the US from Palestine in the 1960s, and still receives accurate news through word-of-mouth, whether it be from friends and family, or women at the local masjid.

But now, our news and information moves faster. For those with access, social media has intensified the speed and broadened the scope of word-of-mouth communication and traditional media. It allows deeper dives, rabbit holes, opening a massive space for learning and unlearning, absorbing and shifting. It chisels away at the dam of censored narratives and lays bare the phony integrity and Western hypocrisy, exposing its violent complicity and exploitation, and the destruction it unleashes around the world.

Palestinians are livestreaming their own voices, louder and clearer than ever – the resistance, journalists, teachers, doctors, and civilians – who are capturing their world so we might bear witness. Since the start of this genocide, we’ve seen glimpses of the well over a hundred thousand Palestinians martyred at the hands of the settler colony “Israel” and the US. Standing resilient, Palestinians continue to post on social media, showing us their fight for liberation through pictures, captions and videos, working around the censorship and surveillance of the Zionist founders of these platforms.

While the narrative shift driven by the spread of information has been dramatic, also creating new audiences and communities, the same pitfalls of social media persist, including trends, clout-chasing, propaganda, and scams. We see the centering of so called pro-Palestinian organizations that are funded by Zionists, rising profits of clothing brands that claim to be donating profits to aid charities in Palestine, and the apolitical celebrification of the Palestinian resistance. Such shifts, many of which are disturbing or even dangerous, are rooted in Western capitalist values that objectify and exploit in the name of profit, also augmenting the stark disconnect between the material realities of Palestinians living across fragmented geographies.

Engaging in this fractured social media landscape – which is often also a site of shadowbanning, silencing, and surveillance – means also engaging in politics and deciphering intention. Whether it be through creating content, reposting and sharing information, initiating commentary about a media piece… What are the stakes of posting about Palestine, today? How can our intentions become messy in the battle for visibility? What is actually helpful, and what are we working toward? What is the meaning of decolonialism in this online ecosystem, and what is the line for our social media generation?

The below synthesizes a number of debates around content creation on social media, namely Instagram, from a diaspora perspective, and offers questions for us to reflect on collectively about the ethics of “posting Palestine” at this moment.

Creating “content” and framing the narrative on social media

Picking up the content creation torch in terms of Palestine appears to come with two paths. One uses creating as a way to share knowledge and/or experience, also initiating collective reflection for further action. The second is creating purely for self-interest and monetizing of the social sphere via views, likes, and follows.

“Content creation” is a vague term that encompasses the framing of narratives on social media, but this practice is much bigger than the term gives credit. Creators poke holes, both in exposing the “Israeli” propaganda machine to the brainwashed West beyond repair, and in exposing individuals who leech off Palestine for future gain.

But social media literacy is tricky. It requires learning to be intentional and critical of our moves in this space. The terrain is ever-shifting and cross-generational, cut through with issues of censorship, blindsides, and sensitivities. It also depends on demographic and slick algorithms, making navigating it feel like a battle of attention, learning, unlearning, and sifting.

But it can also serve as a bridge, bringing communities and tying struggles together. It sheds light on topics and makes us realize that they aren’t as fragmented or disconnected as they may have seemed previously. This shift is caused, in a large part, through the videos and photos of their Instagram feed — the Genocide is livestreamed. Instagram offers an access point to different realms and societies, from Palestine to Sudan, beyond our small corner of the world. But again, what you see depends on technological and linguistic access, who you follow, what you search, how you engage with content, and more. Algorithmic processes to keep our eyes hyper focused on our screens for hours on end have openings and limitations.

News Coverage

At the forefront of social media and Palestine is the pursuit for fair and accurate news coverage. Sources well known in the Arabic-speaking world have been censored and banned from many social platforms, while new ones rise in pockets of the social media sphere and continue to spread truths.

Choosing which news and news platforms we engage with has never been more pivotal. We’re past the days of tuning into manipulative Western sources for accurate news; they’re a mockery at best. The news we pay mind to and the platforms we seek it from are intentional choices we all make every day. With Palestine, we’re tuned into the voices on the ground.

Artwork by Dhia Dhibi: RELAYS

Printed fabric embroidered with relay components, stuffed with wadding and attached to a wooden hanger.

Featured artwork: CERAMIC CAPACITORS

Printed fabric embroidered with Ceramic Capacitors, stuffed with wadding and attached to a wooden hanger.

Independent journalists in Palestine have been reporting news of occupation for decades, and now Gazans are using social media to report on genocide. Their lives are at risk and hundreds have been targeted and killed by “Israel” while exposing the truths of the violence. This social media environment has been their base to document and share news while debunking imperialist propaganda.

Education and Organizing

Social media allows for many avenues for those creating and engaging, and the role of educating and organizing has been a crucial piece to the global narrative shift. There are Gazans sharing current news, or debunking “Israeli” propaganda, and Palestinians in the diaspora, filming videos of themselves sharing Palestinian history. There are others creating community-based content to mobilize and call people together for direct actions to halt weapon shipments or to initiate building sustainable mutual aid efforts. And in all of this posting and reposting, there’s major risk of targeted killings, violent suppression, doxxing, and more.

This kind of educating and organizing involves listening and centering the indigenous voices, namely what Palestinians in Palestine are saying, and then determining how to reverberate these principled sentiments in productive ways. Something we have heard time and again is that these forms of dialogue, education, and organizing should keep Palestinian voices at the center, rather than simply spotlighting the diaspora and non-Arab voices. While the line between these can be unclear, engagement must be calculated, disciplined, and intentional. Doing so shares news and shapes solidarity structures that link the region and diaspora, and can even fuel the waking up of people in the West, challenge complicit behavior, shift indoctrinated toxic beliefs, and support efforts to place power in the people. Absorbing these forms of “content” can shatter worldviews, depending on who and where this person is taking it all in.

Clout Chasing and Profiteering

What is curious is that, even though we know the shortcomings and complicity of mainstream Western media, that some continue to put these sources on a pedestal when they “get it right.” This is, perhaps, more prevalent in older generations, but it makes me wonder why this is, and what it would mean to pay these sources no mind? They tap into the truth with the ill intention of regaining the trust of what they may deem as a desperate or wandering audience. Just as those who swoop in on “causes” for personal gain.

But we’re walking contradictions. We disrupt for Palestine, yet live in the imperial core where our tax dollars directly fuel genocide. We seek community, but our moves to grow those communities often take Western-driven forms of consumerism and celebrification. The vast gray area that opens with the contradictions of content creation and engagement with Palestine can unfortunately muddy intention. Therein lies our pitfalls.

With visibility of Palestine uplifted through social media, we continue to witness plenty of clout chasing and profiting off genocide in the past year and a half. When is what’s being created, posted, or talked about, merely performative and for individual gain? And, when is it rooted in authentic intention to connect, educate, and make supportive change? How can we tell?In the “attention economy,” social media carries the dangers of trend labeling. Masses of people jumping on topics, exploiting real, offline movements for profit and power. They gain clout online, growing quickly through continuous posting of trauma porn, developing new Palestinian brands, marketing panels, or advertising dinners that are organized allegedly in the name of genocide but where organizers pocket the profits.

Artwork by Dhia Dhibi: DIODES

Printed fabric embroidered with Diode components, stuffed with wadding and attached to a wooden hanger.

And many buy into these scams and clout-chasing ghouls. Why is this organization flourishing now and where are the receipts of their profits? Who funds this organization, and if Zionists do, why do we continue to support it? Is accepting crumbs in the name of visibility worth our energy in the long run?

This grifting and exploitation of Gazans surviving genocide is horrifying. We should be able to question and discuss intentions behind actions for Palestine. Yet, with a “take what we can get” mentality regarding visibility, calling for accountability feels dangerous. If someone continues to post blood for shock value without further dialogue or purpose other than throwing people into helpless panic spinning, what’s the real intention?

There’s always nuance, with some not thinking through the broader implications of their actions online. Does aid need to be so visible? Is presenting photos revealing the depth Palestinians’ suffering needed to gain organizational growth and support? Why is once helpful educational content now shifting to market your timely clothing brand? Should we be questioning and reevaluating these actions?

How does this look different amongst diaspora communities vs. the Arabic-speaking world, or across generations? Is it that the deeper we are indoctrinated into Western culture and values, the harder it is to decipher these dangerous moves?

Sharing with what intention in mind?

But amidst all these nuances, is it really that difficult? With a decolonial frame, our compass must start with thinking about the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians murdered by “Israel”. It’s about identifying intentions, being transparent about them, and moving with respect. Anything short of this risks losing our humanity.

If your feed is mainly political, these days, you can cycle through the range of emotions — from rage and despair to empowerment — within minutes of opening your preferred social media app. These emotions carry into how we engage and what we share with our followers. If it ignites us to post something on Palestine, it’s helpful to reflect on why that piece of media is important for our circle to see. Vetting and sharing mutual aid initiatives to push community care, or sharing news, violence, archives, videos of politicians… It’s all powerful material, but understanding what these things mean in the context in which we live, and our social circle, matters most. There’s no single rubric or right answer.

Engaging in commentary

Joining discussions and initiating commentary is another decision we make when showing up on social platforms. There are so many factors influencing our engagement in this bid for dialogue, whether that be through asking questions, venting, stating hard opinions, analyzing, or critiquing. Some of us have a large-scale following and some have a small, intimate circle of followers, and we are speaking to different local contexts and demographics. By sharing commentary on Palestine as another route to narrative (re)framing, there’s also an intentional release. But what happens when someone on social media, with any sized following list, spews inaccuracies or blindly shares Western-coded views?

In these emotionally heightened times, giving grace and considering nuance to everyone’s backgrounds and learned perspectives of situations is horribly difficult. Granting each other space to get it wrong and try again, or admitting to not knowing enough about something and retracting statements, can be allowed if we let it.

Art Project by Dhia Dhibi: DESENSITIZING CONSENT, 2024

15-piece Installation, Printed fabric embroidered with circuit components, stuffed with wadding and attached to wooden hangers.

Is there time for patience? How is this possible as we watch our brothers and sisters face constant bombing and shelling? Are there ways to engage in discourse on social media without publicly shaming each other? Can our anger of disagreement be approached differently? Are there ways to redirect through understanding and care rather than for personal ego boost? Is there a way to do this in a way that doesn’t deepen the divides that “Israel” and the US crave to produce among us? Perhaps “conflict-resolution” in social media communities begins privately through direct messages, where there is perhaps minimum discomfort. In what cases do we escalate this, for example, in the case of large-scale grifters who might say the right thing but don’t follow through with their money through boycott?

This idea of giving people more than one chance to correct and redirect themselves gets tricky, and public call-outs intended to protect the community are necessary in some cases. But these lines are ones we need to define, together. We should work to redirect each other, even within the community, and call out falsities and grifting, but the question is how and to what end.

I believe that social media can be a community environment, and making this community disciplined on Palestine can lead to more enduring impacts. That’s how we make stronger, more principled moves forward. We learn that best from the resistance and indigenous already moving in these ways.

Intentions, checking ourselves, checking each other

It’s crucial to think about how we’re engaging on social media in relation to Palestine. And ultimately, we all have a choice in how we frame information to our communities online as well as offline. Are we sharing the everyday bombings and bloodshed to allow others to empathize, see, and feel as though they’re connected, or to compel them to take action? Are we posting debunked propaganda to educate and help others look out for it in the future? Are we posting to simply remind people that the Genocide is still happening, and even intensifying?

“Creating” or expressing knowledge through media is a bridge towards momentous action. And this idea of creating is reflective of our shared power, in that, we can all create, absorb and take on responsibility for this collective action.

Social media serves as a (partial) mirror and sounding board to our lives, movements, and how they impact justice for Palestinians in Palestine. It’s highlighted our interconnectedness and with that. There’s no claiming that we “don’t do politics.” Our eyes on the screen are political, as are our choices about what to or not to follow, share, listen to, learn and adopt are political. Avoiding paying attention to Palestine is a choice.

And so, an intentional approach to Palestine on social media can challenge the “disposability culture” of the West: the disconnected “we don’t owe each other anything” mentality, the materialism and consumption, the rampant “Israeli” and US propaganda. Western unease around this is all the more reason to move more cohesively in collective care. And while it’s a risk to show up, these risks are absolutely nothing in comparison to what Gazans and other Palestinians are facing day-to-day. Interacting online does play into the reflection of personal integrity.

While there’s no one right method on how to show up on these platforms, we can move with a more solid foundation of intentionality and accountability. It can be less of a shit storm, and more of a space to flow and learn together.