Words by Papyrus

Featured photograph: Gröndahl Mia, 2011. Tahrir Square: The Heart of the Egyptian Revolution, published by The American University in Cairo Press.

This piece is a supplement within the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Only a few kilometers away, separated from the Zionist genocide of Gaza by only a border, Egyptian youth and activists did not think twice to take to the streets in October 2023 and the weeks after. It is in this strife to mobilize, to organize, to resist that the generation of 1997-2003 was confronted with the reality of what Tahrir has come to mean.

“دلوقتي دوركم… زي ما جيلنا أخد فرصته انتو كمان لازم تتعلموا“

(Now it’s your turn… Just like our generation got its chance, your generation should also learn.)

In the weeks following October 7, 2023, Egyptian youth eager to take action in solidarity with Palestine, found great value in turning to the activist network that was birthed by (and give birth to) the revolution on the 25th of January 2011 for advice and ingenuity: Shabab Yanayer (January Youth). We wanted to ask: in the contemporary authoritarian context, how do we create spaces for resistance?

In one such conversation,1 following a significant setback from the state security forces, someone from the Shabab Yanayer replied with the above quote to a question asked by the (respectively) younger generation. Confused and surprised, it suddenly hit me that relying on the Shabab Yanayer generation is not adequate to address the context and demands of the now. That we are now the youth. And with that, came an influx of questions.

I know that our experiences with the Egyptian Revolution are not one. Whereas they were on the streets, in the Square, on social media, we were children understanding the world by watching the Revolution unfold through a revolutionary lens. And the context has changed dramatically. Tahrir Square, a site for Egyptian resistance, has become a site for the state to claim its hold and normalize hegemonic state narratives. Once a symbol of the people, of change, has become a symbol of silencing and enforced disappearances. From a strong hope for tomorrow, to the deep dismay of the present, Tahrir has watched over Cairene streets as they are taken more and more from the people and tainted more and more by the state.

Throughout this article, I will explore what is the meaning of Tahrir across generations, and who is responsible for asking for it? I use the word Tahrir in a duality, on the one hand to refer to the 2011 revolutionary moment erupting in Tahrir Square, Cairo, Egypt on January 25, and on the other, to mean its literal translation of liberation.

What is a “generation” in the context of revolution?

Relying on loosely defined, transnationally-ambiguous categories like ‘millennial’ and ‘Gen Z’ is not adequate to describe Egyptian youth as they exist here and now. For that matter, even ‘youth’ renders itself a contestable concept requiring further analysis.

While generations are bound together by age, it is far more useful to look at the ideas and knowledge that members of a generation share, than to reduce them to birth years. Knowledge is always linked to its social-historical and existential location,2 and one’s social location is linked to non-concrete class position. In other words, the distinct consciousness of a generation, or the distinct character of a generation, is always closely tied to a formative historical event/s.3

I build on the above to conceptualize a generation as:

A cohort of similar ages, characterized by a shared sociopolitical location. While “tempo of change”4 for members of a single generation is diverse, it is often characterized by their interaction with the same social, political, and historical events.

So, while the members of a given generation are certainly shaped by historical event/s, they also shape it through a process of interactions with it; they impact it in the physical realm through their actions or the mark they leave on it. They also impact it on the symbolic level, through the immortalizing narratives that they pass down. It becomes a dialectical relationship of impacting and being impacted by. We can understand Shabab Yanayer, then, as both shaped by the revolutionary moment and shaping it through their ongoing writing of historical narratives and present commentaries.

In the revolutionary context, Tahrir in January 2011 becomes the formative historical event. On the one hand is the generation that created the moment, Shabab Yanayer, and on the other hand is the generation that now sees the world through this moment, which I will call Awlad Yanayer (Children of January). Of course, this is not to position the generations on opposing ends of a spectrum. Rather, they are engaged in a process of change. Awlad Yanayer, initially relying on Shabab Yanayer to realize their potential as social and political actors, find themselves in a contemporary tempo of change,5 trying to understand what it means to call for liberation in a post-revolutionary Egypt.

On State Erasure

“عمو هو يوم ٢٥ يناير دا اجازه من المدرسة ليه؟”

(Sir, why is January 25 a school holiday?)

As my generation maneuvers the state’s violent campaign to find spaces where liberation can be dreamt of, I fear younger generations lose the essence of the meaning. They are, already, without memory of the revolution, without memory of the power of collective action, and without memory of a life beyond the suffocating hold of the state. Forced to grow accustomed to a stratified Egyptian society, whose institutionalized fragmentation is the fuel that upholds the state’s power, liberation is a distant concept. Year after year, this concept is becoming unwoven from the fabric of society.

Younger than Shabab Yanayer and Awlad Yanayer are the now children and teenagers, whose definition cannot be related to the revolutionary moment. The quote above is a tweet made by a child asking why January 25th is a school holiday. Though an innocent question, it bears the painstaking reality of the current state’s success in erasing the January moment from the physical realm. The Egyptian state carefully constructs a reality where January 25 means only Police Day,6 and bears no memory of a revolution in an attempt at “re-scripting – a reinterpretation of national symbols or key events.”7

Mural in Mohamed Mahmoud St. (branching out of Tahrir Square) in Cairo, Egypt. Photographed by the Author in 2021.

The state exercises its monopoly on the legitimate use of force to the utmost of its ability, controlling material resources, constructing enforcement and punishment, and manipulating the symbolic world.8

This is done in many ways:

- Repression of political organization, or potential political organization, particularly from 2016 onwards, with more strict measures in place starting 2019.

- Preemptive repression strategies, where laws like NGO Law, Protest Law and Terrorism Laws are exercised ambiguously and exist to restrict civil society;

- Co-opting of youth and civil society engagements through state-endorsed groups and platforms, such as the ‘Students for Egypt’ student group;

- Online Surveillance both by tracking social media and restricting certain websites;

- State control of media, and hyper-advertisement of police strength and state successes;

- Whitewashing and erasure of street art and graffiti;

- Physical reconstruction of the city; replacing the open space of Tahrir Square with a hyper-securitized closed monumental memorial.

The reason is simple; the current Egyptian state will not allow the January 25 Tahrir moment to happen again. And so all generations must believe that this organization is not possible.

Beyond Ontology; Towards Intergenerational Knowledge Production

The necessity for intergenerational knowledge production becomes particularly urgent in the context of reclaiming a people-centered narrative of the Egyptian revolution. As the state actively works to erase or rewrite the collective memory of 2011 through the “management and appropriation of meaning,”9 there is a critical need to preserve and reconstruct the experiences, struggles, and aspirations of the revolution as lived, and as its legacy continues to be alive.

In a securitized Egypt, valuing its citizens more as silent consumers than critical agents, the very act of knowledge production is necessary. In the face of hyper-stratification and coopting of political participation,10 finding a space where the January 25 memory can be harnessed becomes the meaning of liberation.11 Liberation from a military security state, towards a country for the people. Liberation from a government silent in the face of Zionist genocide, towards a government protecting Palestinian statehood. In the same vein, creating a dialogue that is intergenerational immortalizes the pain and promise of January 2025, pledging to keep it alive in the future before the present.

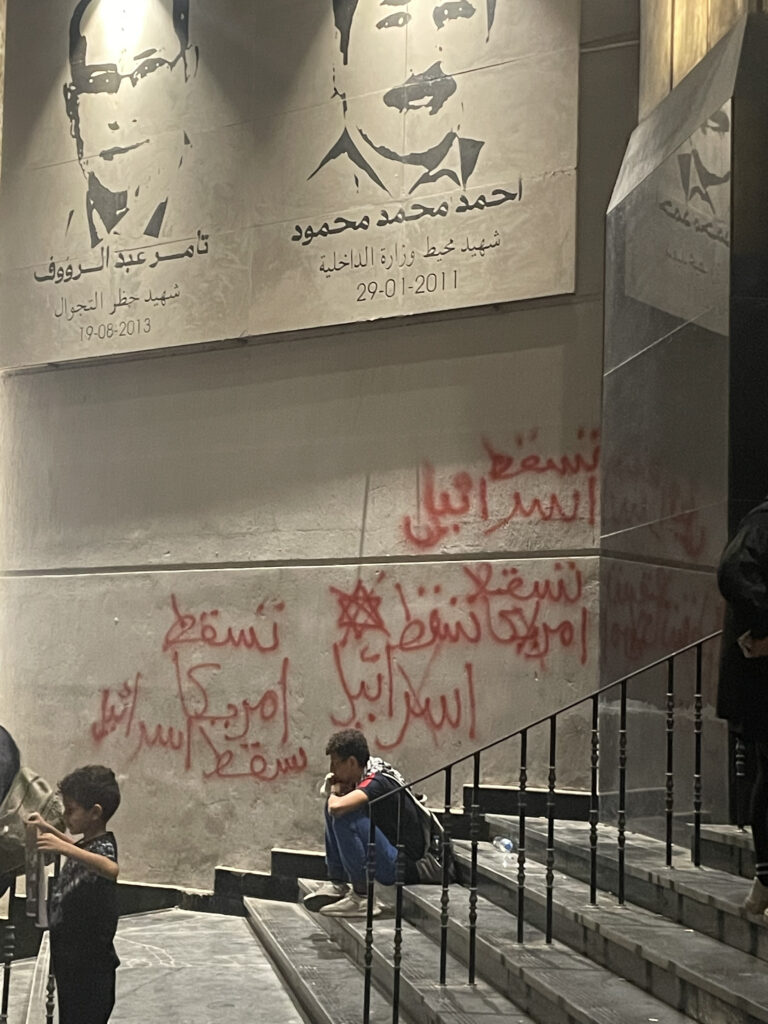

Stairs of the Journalists Syndicate in Cairo, Egypt. Photographed by the author in October 2023.

It is a pledge to keep alive through the (even) younger growing generations so that next year, not one of them is confused about why January 25 is a school holiday.

Whereas January 2011 marked the birth of the generational consciousness of the Shabab Yanayer generation, perhaps this contemporary moment constitutes my generation, Awlad Yanayer’s, generational consciousness.

Learning, (re)learning, and (re)constructing meanings of liberation within and across the Shabab Yanayer and Awlad Yanayer generations becomes, in and of itself, an act of resistance and liberation. This process of intergenerational dialogue allows us to rethink—and ultimately reconstruct—a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of liberation, one that is not fixed to a single moment or outcome but is continuously reimagined through collective memory, resistance, and aspiration. Intergenerational knowledge production provides a critical framework for resisting historical erasure and for developing a more nuanced, multifaceted vision of liberation.

Tahrir, Now?

In many ways, both generations live to commemorate the power and pain of Tahrir Square. Shabab Yanayer saw liberation as the shift towards a democracy and away from a police state. Awlad Yanayer echo this hope, attempting to generate power from engaging with Shabab Yanayer in narrating the revolution and its aftermath. In the hyper-securitized military state of today, Awlad Yanayer find liberation to mean bringing back the Tahrir moment, and challenging the Draconian hold of the military over civil society.

For Awlad Yanayer, the question of reigniting the Tahrir moment lingers heavily. Attempts to answer this question have taken place online, in public and private forums, but it remains difficult to find a new site for liberation amidst the state’s sporadic repression. For a moment, it seemed like the stairs of the Journalists Syndicate, in the heart of downtown Cairo and roughly 1.5 km away from Tahrir Square, was the contemporary site of liberation; the place where we could begin to occupy space. When everywhere else was silenced in Egypt, the stairs rang loud with demands for a ceasefire and chants to cut ties with the Zionist state. But unfortunately, not everyone made it home from the stairs.

Tahrir is a lingering thought… always there, but never within reach.

A liberated Cairo is a liberated Jerusalem, is a liberated Colonial empire. But a liberated Egypt is a faint dream. The military state is but a tool of the global capitalist master. And the state will never dismantle the master’s house, it will build security cameras that further protect and isolate it.

And as always, FREE PALESTINE

Protests at the American University in Cairo, Egypt. Photographed by the author in October 2023.

- I find it important to mention that, although I was not the person directly involved in this conversation, it was shared with me as part of a group aimed at discussing the possible spaces for resistance and mobilization in the contemporary Egyptian climate.

- Jane Pilcher, “Mannheim’s sociology of generations: an undervalued legacy,” British Journal of sociology (1994): 481-495.

- Aparna Joshi, John C. Dencker, and Gentz Franz, “Generations in organizations,” Research in Organizational Behavior 31 (2011): 177-205.

- Karl Mannheim. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. First published 1923. Edited by Paul Kecskemeti. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1952.

- Pilcher, “Mannheim’s sociology of generations.”

- January 25 has been celebrated as ‘Police Day’ in Egypt for the past 72 years, which triggered the choice of this day for the 2011 revolutionary moment.

- Laurie A. Brand and Joshua Stacher, “Why two islands may be more important to Egyptian regime stability than billions in Gulf aid.” In From Mobilisation to Counter-Revolution (POMEPS, 2016): 37-39.

- Lisa Wedeen, Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria, (University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- Ibid.

- Nadine Sika, Youth Activism and Contentious Politics in Egypt: Dynamics of Continuity and Change, (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- Jannis Julien Grimm, “Contesting Legitimacy: Protest and the Politics of Signification in Post-Revolutionary Egypt.” PhD diss., 2020.