In conversation with Dalia Al Dujaili

Photography by Ghalia Kriaa

Stylism by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Stylist assistance by Justine Schwaab

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

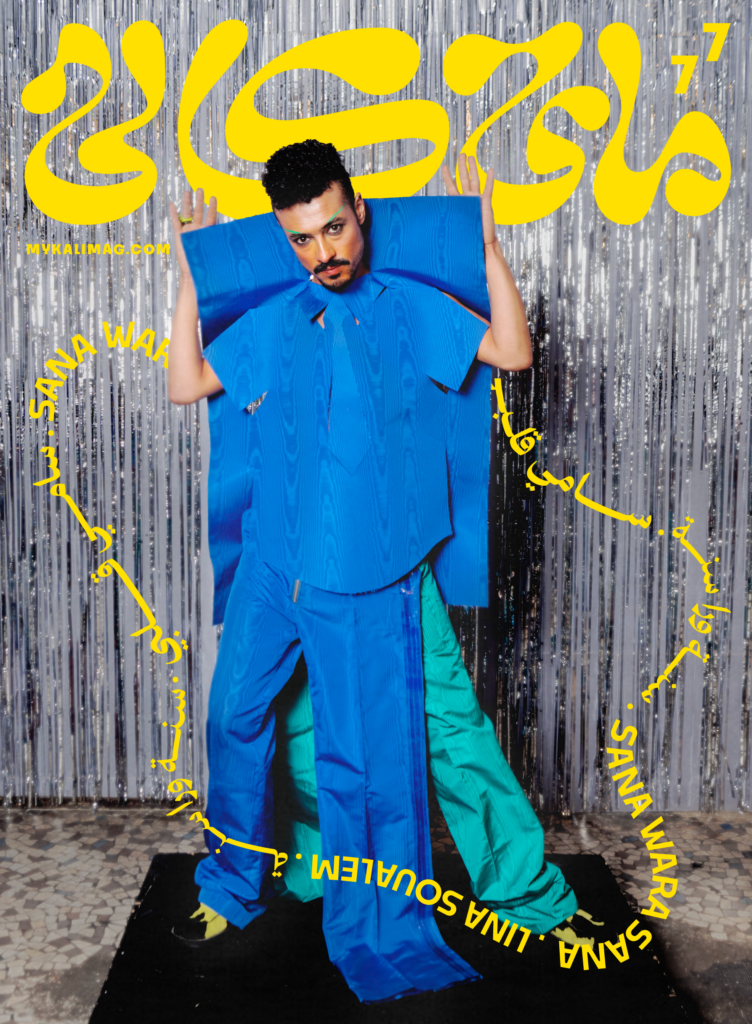

Some stories start with a place. Sami Galbi’s begins in-between. Born in Switzerland to a Moroccan father and a French-Swiss mother, Sami carries the echoes of multiple homelands, not always comfortably. His music traces the cartography of these overlapping worlds: shaabi rhythms wrapped in bass-heavy pulses, lyrics that dance between Darija and diasporic longing, and melodies rooted in the fields near El Jadida, Morocco, filtered through Manchester clubs and Berlin collectives. His breakout music video “DAKCHI HANI,” with its surreal visuals and nostalgic mood, introduced his world of sonic memory and post-diasporic aesthetics to a wider audience.

More than hybrid soundscapes, Galbi is building community across cultural and political borders, whether through decolonial gatherings in Europe or underground festivals in Morocco. His music questions, connects, and resists. It holds the tension of being called “half-half,” while asserting a wholeness that refuses to be split. The music speaks of grandparents and migration, of shame unlearned, and of joy reclaimed.

In this conversation with Dalia Al-Dujaili, Galbi reflects on the long journey home – not to a single country, but to a self-made of many. A self that remembers, reinvents, and insists on dancing anyway.

Coat; Maïlys Pereira. Pants, Shoes; CamperLab. Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa. Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

To start, can you tell me a bit about yourself, your upbringing and early influences?

I was born in Switzerland and am still based here. My dad is Moroccan and my mom is French and Swiss, so I grew up in both of those cultures. I spent more time with my mother after my parents separated, but I used to visit Morocco pretty often, maybe once a year.

I’ve been playing music since I was around 12. In the beginning, a lot of the music came from my parents. My mom was a fan of French pop disco and such things. My father listened to a broader range of music, from North American folk music to blues and soul – a lot of Black music cultures – and, of course, Moroccan and Algerian music, including ‘80s and ‘90s rai and shaabi.

Eventually, I found my own trajectory. I was socialized in the late 2000s, with early minimal, techno, and house music, as well as jungle and drum and bass. When I was 18, I moved to the UK and stayed in Manchester for six months. At that time, bass music was really big, and it’s a huge influence now.

Thinking about your trajectory, when did you start playing music seriously?

I first learned guitar, then took singing lessons and joined a school chorus. After that, I continued teaching myself and eventually started playing in a number of bands. The first was Irish folk music – it’s pretty far from what I do now, but funnily enough, there’s a connection. Like my current work, it’s rooted in melody and rhythm, and is in the realm of folk and popular music.

Later, played in a reggae/funk band. Then, about two years ago – just before starting this current project – I started playing with an Algerian friend. We were mixing alternative psychedelic rock and shaabi, but with a more Algerian sound. Now, I’m doing my own compositions, which slide between the main influences, including shaabi, but with an approach that blends elements of hip-hop, bass, and pop. It’s very clubby and danceable.

In the ‘90s, being proud of your identity was not a thing, and assimilation was part of that – it’s why my father didn’t teach me Arabic. It’s the work of a whole generation to take back this pride.

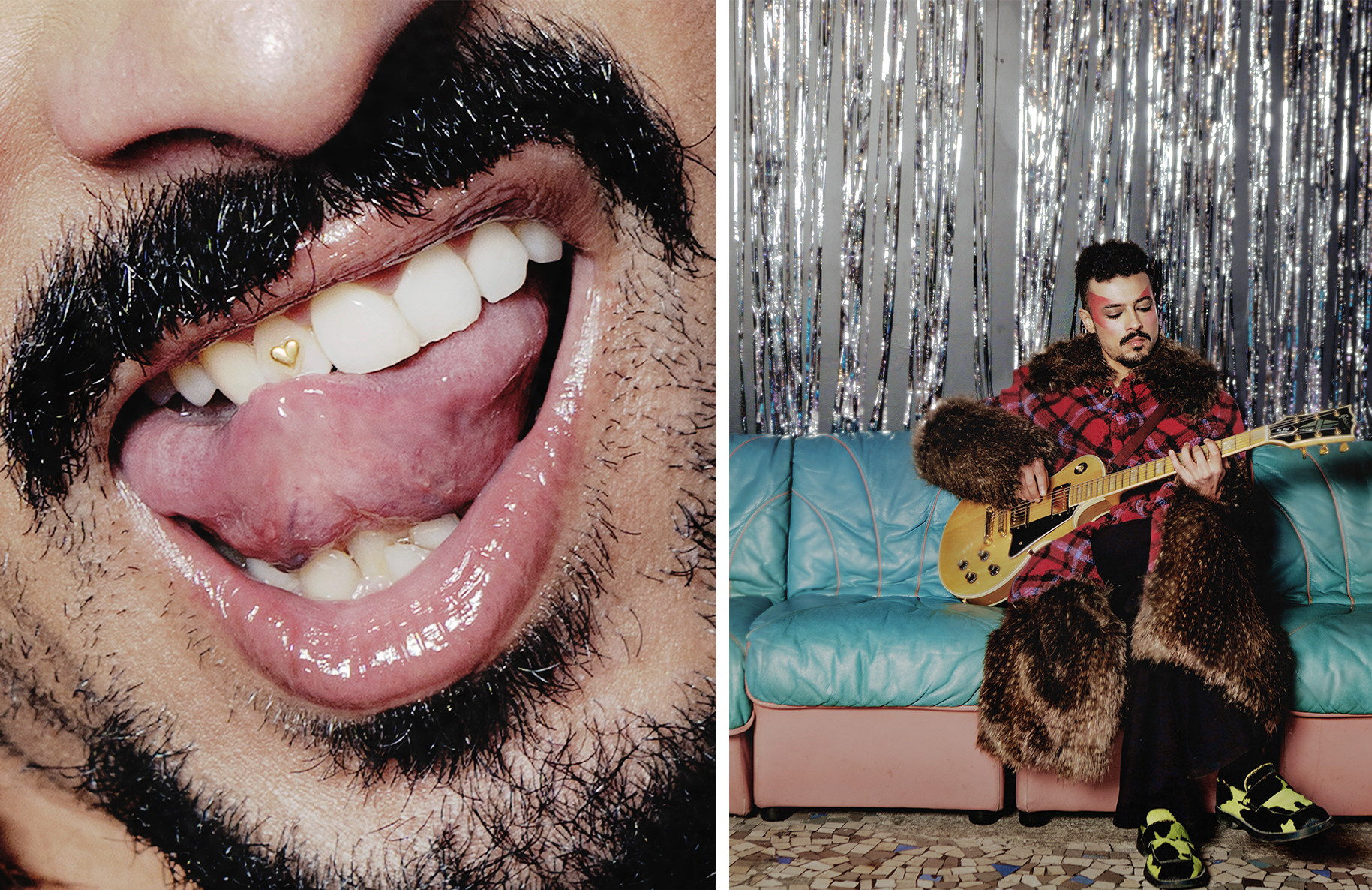

Veste, Pants; LOUTEH. Shoes; CamperLab. Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa. Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

When you’re raised in diaspora, there is often a long journey of returning to the music that our parents were listening to growing up in their homelands. Was this journey the same for you? How were rai and shaabi part of this?

It’s a perpetual journey – when you start, you don’t really know when it will end. I’m trying to take distance from identity as a theme. It’s a driving energy from the beginning because, for example, I wasn’t taught Arabic or about Islam as a kid. It was a double absence, because I was also a stranger both in Switzerland and Morocco; I didn’t have the codes, language, or religion.

I was making stupid mistakes at dinner, for example, saying things that would shock people around the table because I didn’t have the codes and people needed to translate for me. It was taking so much time, and I didn’t feel I belonged to this culture in the beginning. But when my father went back to Morocco, and I was going back and forth, I decided to learn the language to know more about the country, not just my family, but the society in general.

The turning point, for me, was when I found out about queer and anti-fascist communities and festivals in Morocco, most importantly, organized by Moroccans. There were a lot of free parties and raves organized by white people in Morocco, which I didn’t want to go to, and then I found out about this Hardzazat Festival. I went, and it was the first time I was really in contact with Moroccans who were doing the same things as I did. They were politically-engaged artists, doing things like producing events with very little means. I got to know the community and connected to it.

Because of this, I went back to Morocco for three months the following year and registered for lessons in Moroccan dialect. I really wanted to learn what people said in everyday life, and it made me feel like I could really be a part of it. But I also really reconnected both through music and through political engagement.

I was then able to connect more with the diaspora in Europe, and I started to go to more decolonial events and cultural concerts, DJ sets, and community meetings. We were all speaking about the same issues: this double absence that we have to fight against to find our roots in both cultures. Now, there’s a really transnational community that is organizing and mobilizing, especially since October 7th, 2023. Even before then, people were organizing around themes of queer-feminist issues as a part of anti-racism, anti-fascism, anti-Zionism, and so on. I’m really proud to be part of that community.

Top, Pants; Atelier Lilian Navarro. Shoes; CamperLab. Rings; Le Manso. Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa.

Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

You sing in Darija and it sounds almost fluent. Is singing in Darija part of an effort to connect with your roots? Or, was it an effort to formulate an identity within Switzerland?

I think both are connected. For example, I was writing songs in a way that my family would also connect with. I then got more interested in the local music of the place where my grandmother was from – in the countryside near the coastal city of El Jadida – and would ask about how their life was before. Both of my grandparents worked in agriculture. Their region is well-known for the local festivals and fairs, where people would sell agricultural products and have food and music.

The local music is called aïta which means “the call” or the moaning. It’s a music from the Moroccan countryside, and my region, and was common at celebrations like anniversaries, weddings, or agricultural fairs – music is everywhere in old agricultural and popular life. There are also different musical genres and forms, for example, for when people die. Before marrying my grandmother, my grandfather used to know shikhats, which are the Moroccan women singers who used to lived in the same neighborhood. It’s a very special character of this society. These women were very respected and admired for what they did, but also disregarded as being involved in this musical and night local scene.

This music helped me find a link with how life was before, and it was a subject of conversation I shared with my grandmother. I was interested in her life, primarily, but there’s also a song I wrote that is almost the exact transcription of a conversation I had with her. The song is called “Aruina,”, which means “water us,” like watering a plant.

There’s a big taboo in Morocco around identity because of the Arabization of the culture. This was more prominent in some regions more than others, but in my region it is very strong. It’s also known to be religiously conservative. I think my family – as well as other communities throughout this region – progressively forgot their roots because it was not a good thing to be seen speaking Amazigh, especially in public spaces. And, the more Arab and Muslim you were, the more job opportunities you had and the more respected your family became. I would ask my mother, you say we are Arab, but how can you prove it? I wrote a song about that, though she never actually told me everything I was looking for.

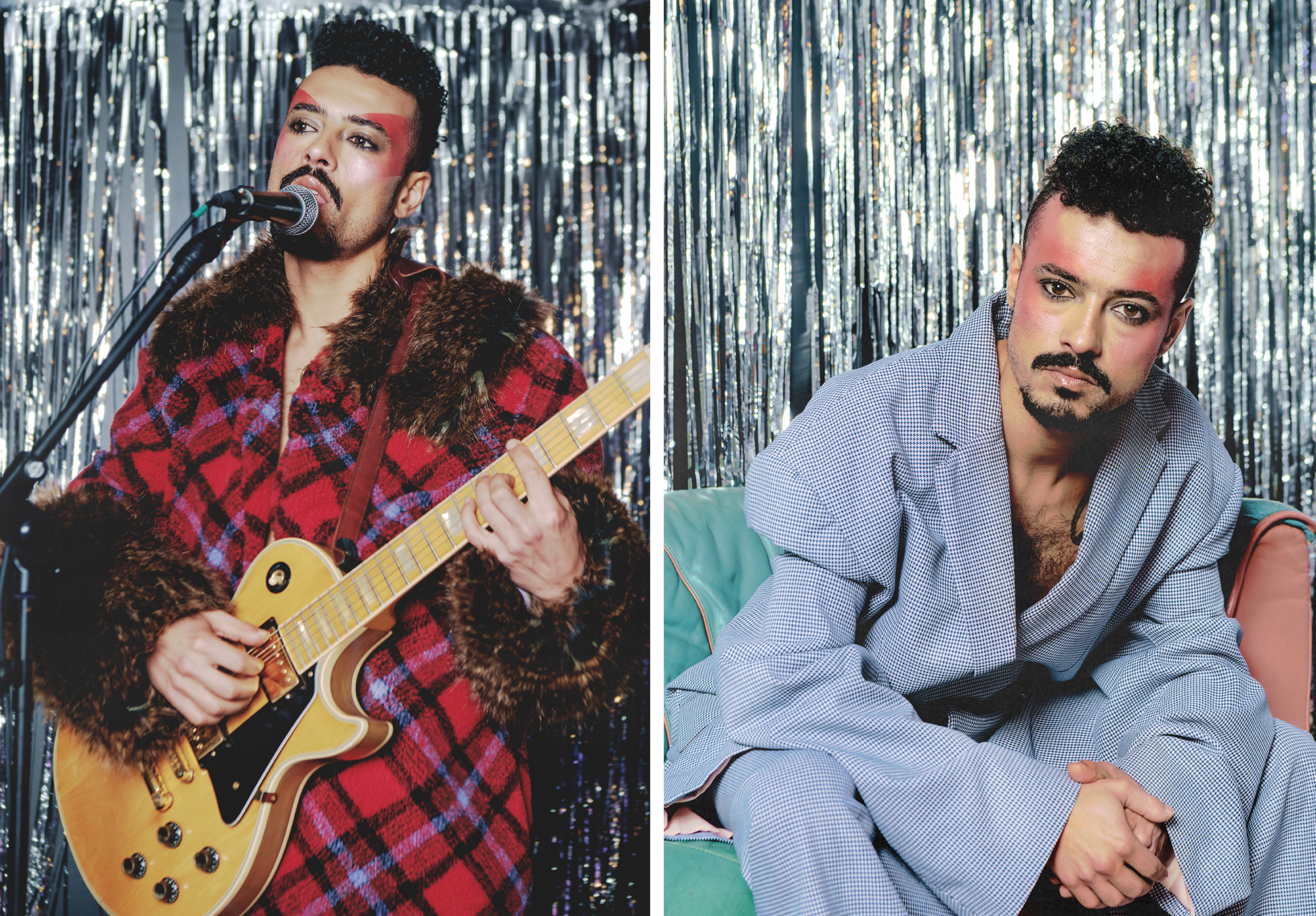

Outfit on the left: Coat; Maïlys Pereira. Pants, Shoes; CamperLab.

Outfit on the right: Veste, Pants; LOUTEH. Shoes; CamperLab.

Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa. Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

What’s interesting is that, in your ancestry, there was both this pressure to assimilate to Arab society and distance itself from any semblance of Amazigh identity, and another pressure for your father to assimilate to European society and learn French and forget his Arab and Muslim roots.

It’s true. There were many steps of being ashamed of our roots and origins, in Morocco and through different forms of colonization. I can’t call it all colonization, exactly, but it’s the Arabization and then French colonization in Morocco, and then a simlar dynamics in Europe. In the ‘90s, being proud of your identity was not a thing, and assimilation was part of that – it’s why my father didn’t teach me Arabic. It’s the work of a whole generation to take back this pride.

I think we’re in such an interesting generation, growing up in the post-9/11 era. I wonder how your upbringing, in school or otherwise, impacted how you’re making music now. You seem so connected to your roots in your music, and I wonder to what extent your heritage was accepted or seen as taboo by those around you?

I think what you said about 9/11 is important, as these dynamics last until now. Just before that were the only “three golden years” of Arabs in the French culture, mainly after France won the 1998 World Cup and their main star was Zinedine Zidane, who is Algerian. At the same time, the Arab-French humorists had a big echo in the media. At that time, it was okay to be a funny Arab or an athlete, that made the French proud of them.

Then came 9/11 and then the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Then it was 2006 and the Lebanese-Israeli war, and then the Arab Spring and Syrian war. From 2001, it’s been really hard to be Arab in Europe, and probably also in the States. Knowing that, my personal situation was different because my mother is also French, that probably made it easier for me even though she was also an immigrant to Switzerland at that time. It’s also a different culture, even if it’s the same language, and you’re not seen as a national.

What has changed didn’t change because of white people or the dominant in society, but from us and our decision to be proud of our cultures. Maybe it’s that we have a whole generation of people that didn’t feel at home in Europe during this time, and they have something to dig into with the history of our parents. I think they also see how beautiful our cultures are and how necessary it is to show people that it’s not like the mainstream media depicts, with religious radicalism and terrorism. We also know how to use social media better than Europeans, and we’re not ashamed of liking or sharing or following people. There’s a lot to say through art, but also through humor. For example, I get lots of messages from people just sending me funny videos about being Arab, and I think this is something that was missed.

You don’t want to be called half-half, because you cannot cut yourself in two parts. Of course, I have certain privileges – like the ability to go back and live in Morocco, or to choose belonging – but maybe there’s a third identity that is both at the same time.

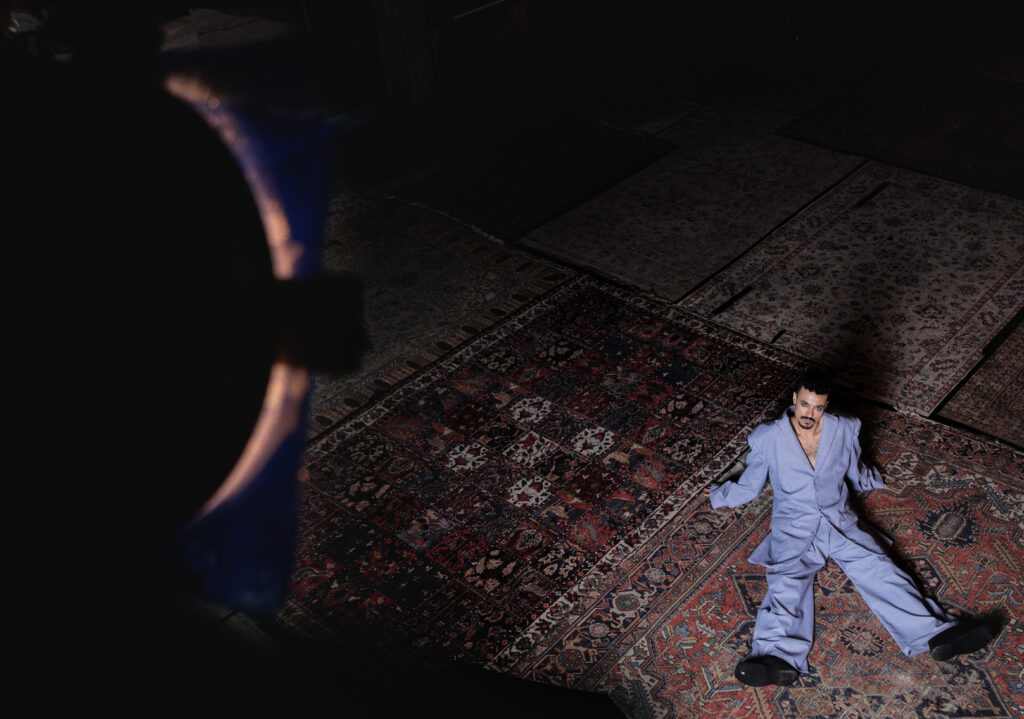

Shirt, Skirt; Maïlys Pereira. Shoes; CamperLab.

Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa. Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

How do you think these dynamics – the complexities of place and identity – come through in your music?

So, I’m not playing traditional rai or shaabi – it is rather a hybridized music. Even what we call “rai,” referring to the 80s and 90s productions, is already a sort of 2.0 of some kind of music – it was already at that time mixed with French pop, funk, reggae, hip-hop and more. In the same way, I’m playing the music of my generation and my identity in its plural forms. People used to tell me you’re half-half, but I’m 100% of both. I think we are going in this direction where more and more people cannot be placed within a singular social category. We carry the histories of our ancestors, but we also have our own trajectories.

Your music seems community-driven, even in your videos and when you’re performing. I can’t stop thinking about the fact that the music you play is intended to be enjoyed in company. In recent times, we’ve lost a lot of communal spaces that previous generations, like our parents, probably had more access to both in the Middle East and in Europe. How do you think your music fits into a time when we’re trying to keep community together while losing a lot of the spaces we need to listen to music together?

There’s a difference between what I would like in the ideal world and what I actually can do. You get offers, and then you try to get booked in certain places, but not for the same reason. For instance, I’m often booked at events where I’m “the exotic act” of the evening, or I’m playing on a world music stage at a big festival. They’re not bad stages and I know a lot of friends have been through the same things, but the community is rarely there. You get people who are pretending to dance like the Disney cliché of a pharaoh, for example, thinking that’s the way people actually dance. And, it’s not always easy to cope with organizers who want to call your sets “oriental electronic.” You have to keep telling them it’s not the way I want it to be presented. But, these opportunties are also important, profesionally.

And then, there’s the alternative/community based and political events often organized by non-white people or allies in mixed groups. There, most people understand my work. It’s actually a safer space. There is not always good compensation at these events, but they give a meaning to what I do. The people and place make me feel understood and supported, and this is such a necessary thing in this industry.

You have to do both if you want to work as an artist full-time. I’m doing this full-time, and I cannot say finances are not an issue. I’m playing with other musicians and touring with a sound engineer, and I have to pay them also. You end up taking jobs knowing it’s not going to be the best show, but that it’s good visibility and a good fee, and they have good conditions.

You were talking about fewer spaces than there used to be. In Europe, I think that more and more people are interested in launching these spaces. For example, there are now many collectives in Europe focused on SWANA music. Some promoters are interested in it for commercial reasons, but some really understand what we’re doing and why. And some jobs, you do for free because you believe in the project. This weekend, we have our first event in Lausanne in my city, which is a big step for me because it’s in a proper club that has public funding and good material. We’re doing this AYWA event, and it’s an apartheid free zone. It’s on us to take some of the unpaid labor of educating people, but I think people in Europe are becoming more aware.

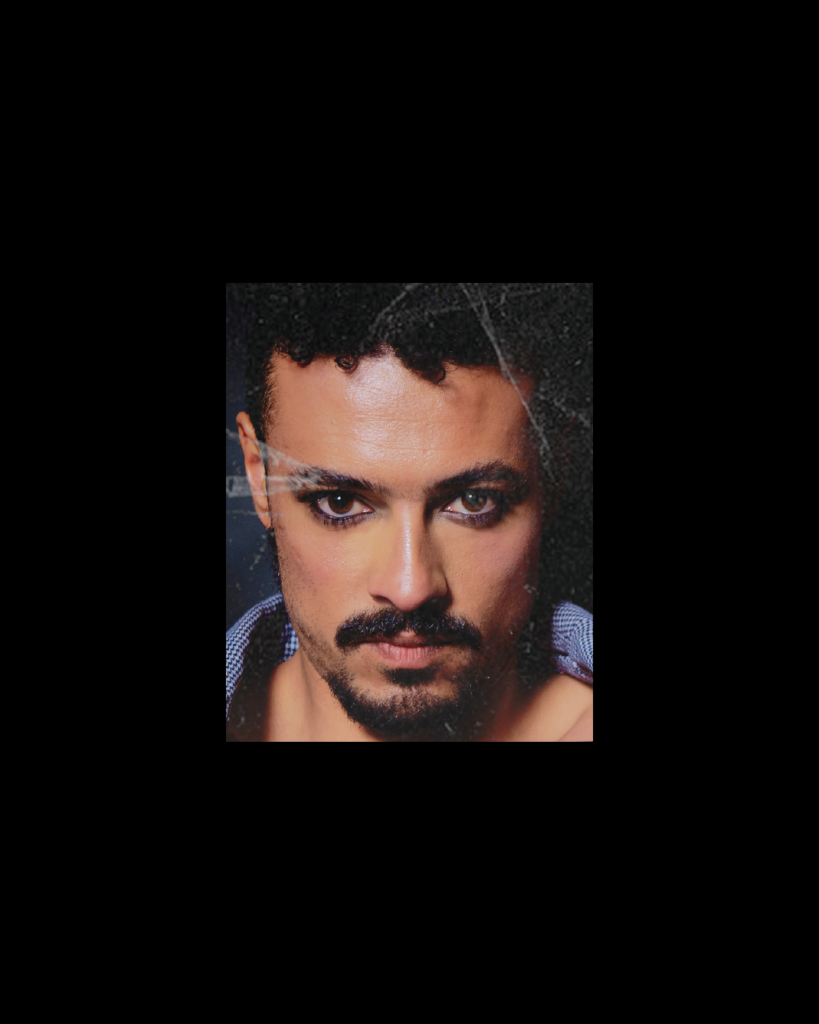

Veste, Pants; LOUTEH. Shoes; CamperLab. Photographed by Ghalia Kriaa. Styled by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

I wanted to wrap up our conversation by talking about what you’re working on now and what’s coming up in the future. Do you have any singles or an album coming out soon?

There is an album coming in May. The two singles of the album are about the themes we are talking about right now. The first is called “Valisa,” which means suitcase in Moroccan Darija, and it’s actually about our conversations with a DJ friend who is also Moroccan and French. The suitcase is a metaphor to symbolize our own experiences, and the things we carry around and share with other people. The song is based on a real story. My friend was visiting me in Morocco. She went back to Europe for a big festival, and she gave me her suitcase to watch until she came back to get it. She told me to take care of it as if it were my own, and that there was a drum machine inside that I could use. She never returned, so I had to carry it with me from Morocco to France. This is the chorus.

The second single is called “Transit,” and it’s about identity, about being a stranger in both places. The main thing is that I’m not a stranger – I’m old blood, a son of this place trying to fight against both rejections.

On the cover: Sami Galbi

In Conversation with Dalia Al Dujaili

Photography by Ghalia Kriaa

Stylism by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Stylist assistance by Justine Schwaab

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue