In conversation with Khalid Abdel-Hadi

Translation by Hiba Moustafa

Photography by Ismaïl Sabet

Styling by Maha Hamada

Makeup by Mariam Habashi

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

When we talk about art, we’re not only referring to the aesthetic forms or media, but also to a vision that extends beyond the traditional exhibition space – encompassing identities, history, politics, and intimacy. In Egyptian artist Mahmoud Khaled’s works, archiving and imagination, documentation and re-imagining, and the private and public intersect. The most distinctive feature of Khaled’s experiment is how he moves between real and virtual worlds, using ambiguity as an artistic tool and providing a space for asking questions more than giving answers.

My interest in Khaled’s work stems from his approach to memory and history – both private and public – that serve to challenge prevailing stereotypes. This interview revisits some of his career milestones and reflects on the recurring themes in his work, including voyeurism, the internet, the body, queer identities, and lost or imagined archives. We talk about his work on digital spaces from the early days of the internet to OnlyFans, his explorations of masculinity in different social contexts, and his concerns as an artist seeking to create works that cannot be confined to a single category. And, we discuss archives, not just as a documentation tool but also as a means for survival, the relation between art, and power and how an artist can be a witness of their era without necessarily acting as a historian.

This conversation is less of an attempt to understand Mahmoud Khaled’s work, and more a natural extension of his artistic method – a space for interpretation, research, and rethinking what is seen and what remains hidden. Our conversation spanned topics of art and identity, Cairo and the various cities he’s lived in, and the generations that have shaped his artistic consciousness and the generation he speaks to today. How does our relation to time and place change when we try to create a new narrative of them from a personal perspective? How can art create a space for questioning what we inherit and what we choose to leave behind?

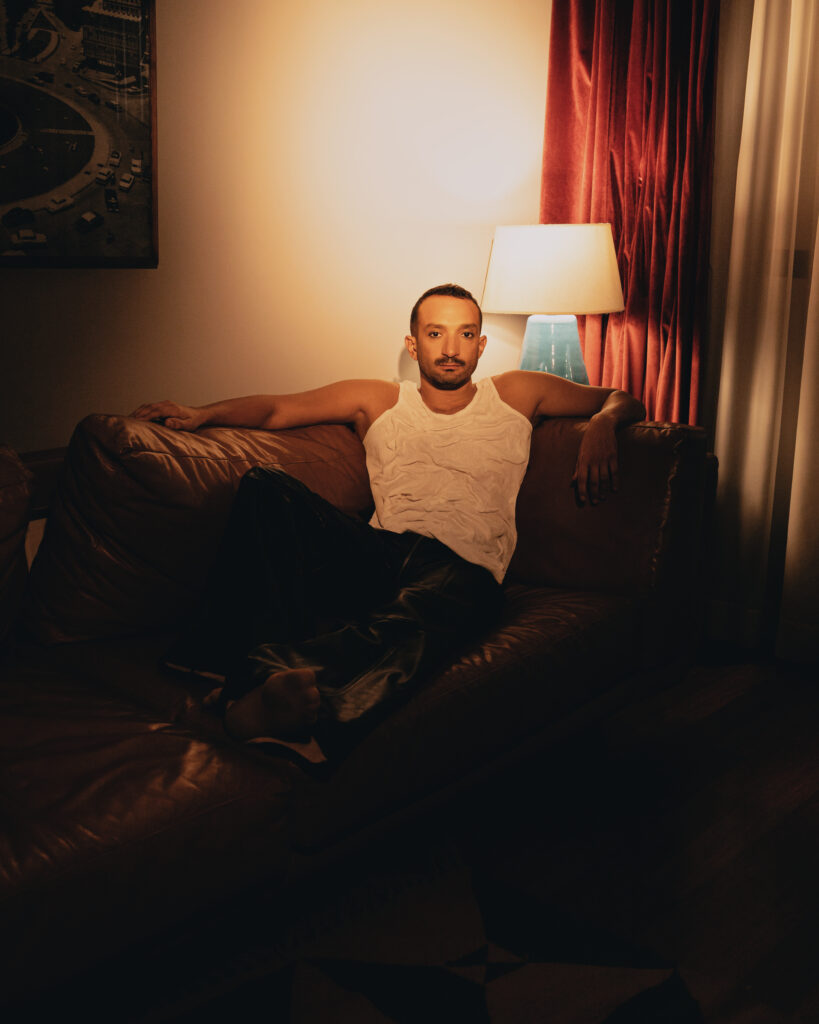

Top; custom made by Borderline The Label. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi. Featured Image retouched by Ali Sadalh.

Examining your earlier works has been very inspiring. Not only did I notice a recurring rhythm in your works, but also elements that you keep returning to, which have become common themes and stylistic approaches in your artistic methodology. For example, voyeurism and imaginary scenarios seem present across multiple works. I wonder, how do the imaginary worlds you create shape the way people interact with your work?

Generally, I think art in itself is a space for imagination and reflection. The question is always: What do I do as an artist? Do I depict reality as it actually is in the artwork, the white cube? Or, should I reimagine my reality – be it political, emotional, etc. – through this artistic space? For me, the white cube is a place for imagination, entirely blank, which gives me a sense of comfort to begin working with imagination or hypothetical visions.

For example, when I am commissioned to create a public artwork, I imagine it as a proposal. But when it becomes something tangible – when it’s produced and displayed in a public space where people would interact with it for years to come – I get nervous because I feel the weight of accomplishing something real and concrete. I prefer to submit proposals and ideas rather than make complete and finished works.

Fictional characters or “imagined strangers” are also recurrent elements in your work. Do you believe that imagined dialogues reflect something about you as an artist? At times, I feel that some of your works are implicitly subjective or autobiographical. Or, do you see a connection between this approach and yourself?

It took me a lot of time to develop a distinctive voice. I was really anxious at the beginning, particularly when tackling personal themes. Over time, I focused on creating a balance between expressing myself and reaching a broader audience. At first, I was afraid that my works on gender identities and masculinity would only resonate with people who cared about these issues, specifically, but eventually, I learned how to try harder to expand the reach of my work. I believe fiction helped me a lot.

Outfit on the left: Top; stylist’s own. Pants; Tommy Hilfiger. Jewelry; Hadde Design Atelier. Outfit on the right: Coat; Meroë. Shirt; stylist’s own. Pants; Helmut Lang. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi.

Your work fills a gap in the art community, perhaps because of the ambiguity in the way you tackle certain social issues, which speaks to society on the whole and not just the queer community. Do you think that your art contributes to raising social awareness, even among those who might not generally engage with these topics or issues?

Sometimes simplifying things is difficult and can have adverse effects. But ambiguity is part of the beauty of the work. I used to believe that complexity was a necessity, but now, years later, my goal is to convey my message in a way that is easy to understand but without being bluntly direct. The goal is to reach a wider audience without the message losing its power.

The place where I live and the limitations it imposes have greatly shaped my artistic language and work. Were it not for these complexities, my works might’ve been clearer. But, as artists, challenges force us to think more deeply and creatively to convey our ideas while still navigating and manipulating legal and societal boundaries.

So, ultimately, the ambiguity and complexity found in your works are a way to preserve freedom and expression without the message being too clear, especially to authorities?

Exactly! Sometimes we’ve to try to outsmart authorities.

We all have to.

It’s an integral part of our tools and the way we all do our work.

This space (OnlyFans) constantly poses new questions, and that’s why I am constantly curious about it – it’s not because I romanticize or glorify it, but because it’s my window to exploring the world with different dynamics.

Top; custom made by Maha Hamada. Pants; Borderline The Label. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi.

Your work, Thanks 4 the Ad/d (2008), is particularly interesting. I love how you used the visual language of infographics to highlight the under-representation of people living with HIV in Egypt. How has it affected people? Do you feel that it has achieved its goal?

The work is one of the dearest to me, and I’ve learned much from it. It dates back to 2008, a time when the internet and social media weren’t as popular as they are today. At the time, I was interested in how people communicated online, especially with the emergence of dating sites like Manjam that were new to my generation in the Arabic-speaking world.

It was striking how some people introduced themselves via profiles openly addressing stigma and shame associated with HIV, at a time when there weren’t open discussions about the topic. Discussions about AIDS were limited to official narrative and film adaptations, which portrayed it as a political and manmade “external” danger, without any real discussion of the experiences of people living with it.

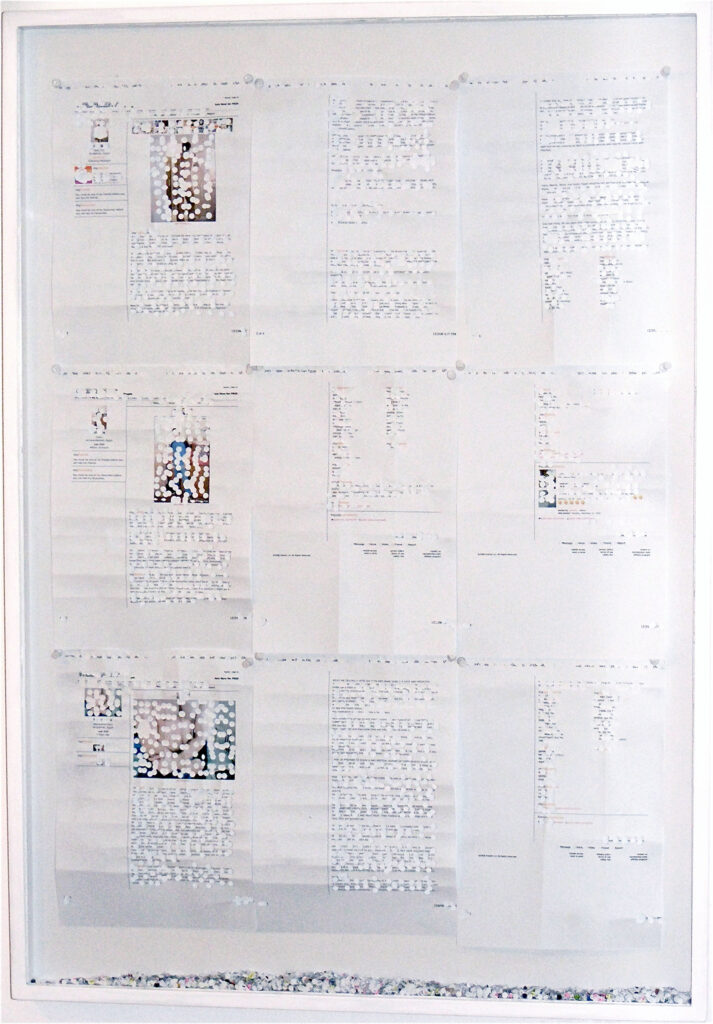

Thanks 4 the Ad/d (2008)

It was inspired by three Manjam profiles, in particular, which I considered visual documents depicting real-life experiences. I wanted to transform them into artwork. The challenge was how to transform intangible online content into a tangible space. The installation was influenced by the architecture of hospitals and the light boxes typically used for advertising that are so common in Cairo’s streets. The idea was how we might take deeply personal content from dating profiles and present it in a public space, in a medical context, which could create a tension between the private and the public.

Thanks 4 the Ad/d (2008)

A lot of your work reflects your fascination with the early internet and what it offered, especially during the 2000s, and voyeurism. This is seen so clearly in your recent exhibition, Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost It (2022), and centers these questions about the digital era, reflecting on intimacy and identity, and its impact on your artistic methods.

The internet has given me a sort of freedom that isn’t available offline, and a limitless space that constantly poses new questions. When we talk about the internet and exploring digital spaces, it feels as if there was a clear plan in my head. This isn’t true.

Even today, when I think about my early projects that addressed instant messaging and dating websites, it seems like these technologies are outdated. And yet, the internet still amazes me with its impact. For example, changes that OnlyFans has brought about in certain economies. This space constantly poses new questions, and that’s why I am constantly curious about it – it’s not because I romanticise or glorify it, but because it’s my window to exploring the world with different dynamics.

I don’t often go out into the street holding a camera to document people’s experiences and interact with them directly. I am obsessed with protecting my solitude as a state of working in the studio, and there, the internet is my tool for understanding what lies beyond. That’s why it still inspires and intrigues me.

Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost It (2022)

I love how you tackled OnlyFans and your ongoing relationship with the internet as a space for exploration. In a way, it seems like your 2009 project Camaraderie (2009) intersects with what OnlyFans offers today.

That’s an interesting perspective. “Camaraderie” was based entirely on videos that I found on early YouTube, when men were uploading their selfies there. It was before Instagram became popular. Back then, I was obsessed with bodybuilding, and I kept questioning the image of the “perfect man” as I saw it around me. While digging, I found a number of videos by Arabic-speaking bodybuilders, especially Egyptians. I dug deeper, thinking about who was behind the production of these videos and how this whole economy worked.

What struck me was the physical intimacy between these men: how they would help each other oil or tint their bodies before competitions, and how this kind of homoeroticism was completely acceptable in this context.

One video showed a gym opening in a conservative, working-class area in Cairo. A man wearing a Speedo stood in the street, showing off the beauty of his body in front of everyone. And in this context, it was not socially shocking at all. But it made me question: when is the naked body celebrated in the public space, and when is it deemed inappropriate? These two questions were the main drivers of the project.

Camaraderie (2009)

Even recently, we’ve seen clips circulating on social media of Egyptian military parades showcasing strong bodies to send a message of the country’s power and security. It’s striking how these dynamics keep repeating, and how they intersect with your work.

This goes beyond the military to art as well. For example, would a scene depicting two men dancing together be received the same way if the actors/director were straight versus if they were queer? I’m thinking about that, especially when I work in an art scene dominated by heteronormativity. One of my projects in Cairo tackled the idea of coupling. It asked: When is it acceptable to play same-sex couples? How does its reception differ depending on the identity of the actors/creators?

You also rely heavily on the idea of the archive – recent and older – in your work, building on and re-reading existing materials. How do you envision archives as linkages between past and present? And, do you ever use the internet in an archival attempt to access queer histories that might be lost?

My work often starts from pre-existing materials—footage, past events, videos that I find by chance. But they are not always “archives” in the traditional sense of the word.

In Egypt, things are complex when it comes to the accessibility of archival materials. Most of the archives that do exist are difficult to access, and you could find yourself facing an interrogation. Why are you doing research? Who funds you? What project are you working on? I don’t have answers to these questions, as an artist. I’m not an academic researcher or journalist; I’m just curious. But curiosity could be enough to make you a suspicious subject.

I avoid official (institutional) archives, instead imagining and reconstructing them visually and intellectually. What can be called an archive today? Is it our old Instagram posts or a collection of photos saved in a private account? These questions remain open and are a big part of my artistic work.

The process you’re describing – this ongoing imagining – is both so present in your work and is an essential part of the process itself. The idea of the archive is exciting in itself, but also comes with risks, especially in authoritarian contexts where even documenting is potentially suspicious. Still, as you mentioned, there is a renewed focus on queer archives – not just Western imports, but as already present in our archives. You are not just contributing to these archives, but also providing new ways to understand and present queer identities in public.

This reminds me of Egyptian writer Iman Mersal, who said something similar when asked about archives. We create archives without always realizing that they’ll become archives someday. If I said I have an archive, I’d be exaggerating or giving the matter undue importance. Ultimately, maybe the photos I take will become an archive one day, when others decide this after I’m gone.

This idea becomes even more evident after a writer or artist passes away. Imagine if Naguib Mahfouz were still alive and decided to transform his house and belongings into a museum – we’d find it comical. But after his death, it became acceptable for people to decide that he, as a prominent figure, deserved a monument of his own in the form of an archive, which can take the form of a museum, for example.

Top; custom made by Borderline The Label. Pants; Farah Seif. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi.

What role does imagination play in how you engage with the past or represent historical narratives in your work?

That’s a great example. It intersects with questions like: What’s an archive? What’s history? There’s no single answer, and it’s part of the same conversation. It ties back to imagination, like we talked about earlier. As an artist, I feel more freedom when I create something imagined rather than something strictly realistic.

For example, if I say I’m working on the queer archive, that would be terrifying – it’s formal and heavy, and I’m not a historian or an archivist. But, for example, if I imagine an archive that envisions a better world in 2075, when there’s an official apology to queer people for how they were treated – I can imagine what form that apology would take, and then develop an idea from there. But if I were told to actually build that monument or memorial, it’d be a nightmare for me as an artist.

Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017)

In your project, Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017), you engaged with the Queen Boat incident. What stood out to me was the way you presented the story and imagined the house, and even the mirrors. How did you tackle this event? Did it affect you, personally, or your work overall?

No doubt. I was at university at the time, and that morning, every newspaper had the same image of a group of men in white garments. Everywhere in the city (Cairo), people had those papers in hand – it was crazy. The men were anonymous – their faces covered, and no one had all the details – and people were referring to them as “the worst thing” that had happened to Egyptian society. One day, I thought that I might be one of them, and that haunted me for a long time. It still does, even after more than 20 years.

Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017)

With time, I saw the picture differently. Even though it was quite abstract and simple, it was loaded with emotional and political meaning, as well as stigma. I wanted to understand how an image became the icon of the not just represent these 52 men but also a larger group, because it was stripped of individual identity.

This work carries a lot of weight. Do you remember how you felt when you witnessed this? Did it mark a turning point in your way of thinking or in your artistic evolution?

It definitely did. Afterward, I found myself constantly thinking about the future of living in a place where, one day, I might be “one of those men” in the newspaper photos. I started thinking about the meaning of alienation, asylum, and exile. Most of the people arrested sought asylum, and those who returned to Egypt later on faced severe hardship upon returning. That kind of public outing — what I call ‘forced disclosure’ in the press – was traumatic. So, I imagined a House Museum based on the concept of exile and alienation. It is conceptually designed to potentially exist anywhere except Cairo, where that incident happened. This decision wasn’t only about censorship; it was about the political and emotional reality of someone being pushed out of their homeland and not being able to return. The project was a meditation on exile as a concept and a state of living.

Did you feel that your art reflects this sense of estrangement? Or, were you trying to reframe this estrangement into something more constructive?

Exactly. The work, for me, became a way to reframe that estrangement and turn it into something productive – something empowering. There’s a privilege in being able to rebuild their world in exile, from afar. And that’s exactly what I wanted to express in the concept of the House Museum.

Even when it comes to dealing with the authorities, fear is no longer as present as it was in the past. This is one of the things that makes me see aging not only as a burden, but also as a strength.

Top; custom made by Maha Hamada. Pants; Borderline The Label. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi. Image retouched by Ali Sadalh.

Do you feel that your cultural or personal identity dominates how audiences interpret your work? How do you navigate that?

Sometimes, yes – but that’s beyond my control. We live in a world that wants to define us through labels. I can accept or reject some things, but I can’t possibly control how others read my work. All I can do is enjoy producing and working in the studio and live my own artistic experience. In the past, I was maybe more concerned with how others viewed my work, but it matters less now. What matters is that I do what I believe in, regardless of the labels people may attach to my work.

This is a constant challenge, but how do you deal with labels like a “queer artist”? Are they difficult to carry?

It can be difficult. At first, these labels irritated me, and I felt boxed in. But over time, they didn’t affect me. At the end of the day, I am an artist – period. The label doesn’t define me. I want to produce work that matters, that reflects my attempt to understand the world around me. I don’t want to be confined by one label, but if people do that with my work, then it is their problem, not mine.

Do titles inspire you, or do they come later? Are there any particular artists who have influenced the way you think about titles or the conceptual framing of your pieces?

Honestly, titles are very important to me. Sometimes the idea comes first, and then I hunt for the right title. Other times, the title leads the work. I don’t think there’s a “wrong or right” way here. But if a title doesn’t come naturally, I usually feel like I haven’t fully grasped the idea of the project yet.

Artists like Max Klinger and René Magritte have influenced the way I think about titles. A title can unlock the reading of the whole work – it’s a doorway to the piece’s message, even when the work itself is ambiguous or symbolic. I draw inspiration from titles and concepts of artists from other eras, and I also work with found materials – classical paintings, online videos, and photographs. My job is to take these materials and transform them into something that’s my own, that reflects my vision, and this is totally part of my labor as an artist.

Necklace; custom made by Maha Hamada. Photographed by Ismaïl Sabet. Styled by Maha Hamada. Makeup by Mariam Habashi.

As queer people, the older we get, the more we realize that our place in this world isn’t what it has been made out to be. Many of us take on a supportive role in heteronormative families, such as a “cool uncle,” while our lives aren’t necessarily prioritized by others. Previously, you mentioned how much you enjoyed my interview with Abdellah Taïa – especially the part about aging and personal growth, and how they shape our sense of relationships and society. This stuck with me, and I’d love to build on that here. In your opinion, how do you think your timeline (in life) has affected your position as an artist? Do you think it’s reflected in the themes you explore? And, how do you view these shifts today, from a more reflective place?

I’ve been thinking about getting older a lot. It comes at a high price, sure, but it also has its privileges. When I read your interview with Abdellah Taïa, I was struck by the way he spoke about age and maturity, and how they shape our expectations of relationships and society. I felt aligned with that, realizing that there were things we thought were possible in relationships before, but they were just an illusion.

In my twenties, I was lost in my struggle with society, seeking acceptance, battling others’ intrusion into my life. Now, in my forties, I’m completely independent. No one can tell me what to do, and I can set clear boundaries – a privilege I value very much at this stage of my life. And yet, there’s also something more complex. Suddenly, you find yourself playing the role of the “supporter” in the family and community — the cool uncle who attends parties, talks about art, masculinity, and femininity – but in the end, he’s most of the time just a side character. I’m not playing the victim here, but it’s a reality that’s difficult to comprehend, at first. Gradually, you begin to accept it, despite the pain it may bring.

But again, there are undeniable privileges. The world treats me with more respect today than it did twenty years ago. Even when it comes to dealing with the authorities, fear is no longer as present as it was in the past. This is one of the things that makes me see aging not only as a burden, but also as a strength.

On the cover: Mahmoud Khaled

In conversation with Khalid Abdel-Hadi

Photography by Ismaïl Sabet

Stylism by Maha Hamada

Makeup by Mariam Habashi

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue