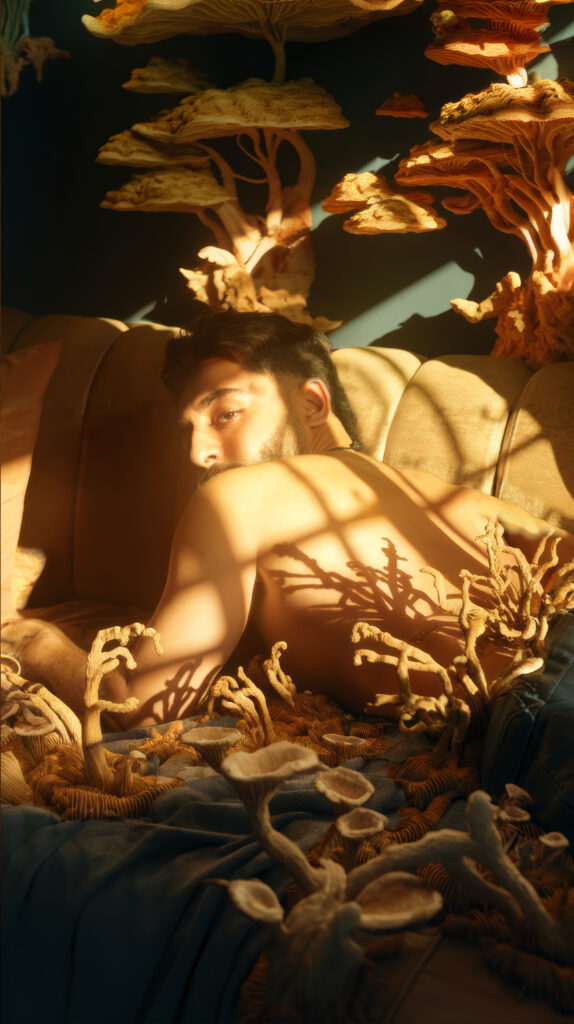

Words and photography by Zeid

This piece is a supplement within the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Trigger Warning⚠️: The following article mentions suicide, mental health issues, physical and sexual abuse.

I can’t afford a therapist, and I don’t have the strength to step outside today. I’m writing to understand myself, to organize the chaos inside my brain. I just turned 25. And I feel like a failure.

I know this sentence may echo in the minds of anyone who’s grown up with trauma or under the weight of impossible expectations. But for me, it cuts deep, because I’ve survived too much to be here, and I’m still stuck. Survival isn’t enough. I want to live. But I feel trapped in every possible direction.

I know I’m smart, just not in the “school” way. And I still don’t know if I failed because I was lazy, mentally ill, or both. My self-disappointment isn’t about capability. It’s about direction. I feel like I lost my compass. Every time I move forward, it leads me back to darker reflections of myself. Every step I take feels like confirmation that I was never meant to succeed.

It’s like running an incompatible operating system. That’s the best way I can describe being autistic in this world. My brain is advanced software, running on traumatized hardware. My RAM is cluttered with ADHD. My processor overheats from overthinking and depression. My hard drive is full of unresolved emotional data. And my graphics card? Burnt out, but still pushing. Because I’m a visual artist. At least, that’s what people call me.

But I feel like a fraud. Always have. Not because I don’t create. But because I never planned this. I started making art on my phone at 17 while stuck in an abusive household. I used a collage app. Played with backgrounds and foregrounds. It felt good. I kept going. It became survival, not discipline, not strategy. Just a lifeline.

I didn’t learn Photoshop. I can’t draw. I can’t illustrate. I never followed tutorials. I just expressed what I couldn’t say out loud. People loved it. Some even exhibited my work. But I never saw myself as a real artist. Because I never did the “homework.”

School was hell.

People think poor grades mean laziness or a lack of ambition, but that wasn’t it. I couldn’t focus. I couldn’t sit still. I was dealing with trauma that nobody could see. While other kids were doing homework, I was trying to survive another night of chaos at home.

I grew up in a deeply abusive, dysfunctional household. My parents were overwhelmed by poverty and religion. My mother was volatile, always on edge. My father was emotionally absent. My older brother beat me, regularly and without mercy. The household operated like a chain of pain: my father humiliated my mother, she took it out on my siblings, and they took it out on me.

There was no safety. Not in the streets where I was bullied, nor at home where I was silenced. I wasn’t allowed to speak. I wasn’t allowed to take up space. I developed a stutter. I couldn’t express myself even in my own language. I was terrified of existing. Apologetic for simply being.

I was bullied for my body, my voice, my softness. I was called a faggot at school. Spat on. Beaten up. Then I’d come home and face more of the same. There was no escape. Just war. I couldn’t focus on school when I spent my nights afraid, my mornings humiliated, and my afternoons trying to dodge more violence. It wasn’t about failing to do my homework, it was about having to survive abuse and still show up like nothing happened.

I mimicked. I studied everyone around me to survive. I built personas. I performed. I became whoever I needed to be to reduce the threat. And I was good at it. I could charm, entertain, shape-shift. But I was never me. I was never allowed to be.

I was surviving a system. Not just a household, not just a city. A violent system that brutalized anyone who didn’t fit. One that stamped out softness, creativity, queerness, neurodivergence. One that fed on conformity. Morocco is a machine, and I was the irregular part.

My first sexual experiences happened when I was very young, too young to understand what it meant. But I knew I wanted to feel safe. I knew I needed to be protected. And I understood early that desirability had power. Even as a child, I recognized how women used their bodies to survive. And I started imitating that, not because I was feminine, but because it was the only script I had.

But I wasn’t happy with my body. I wasn’t comfortable in it. I didn’t feel beautiful. I was hairy, fat, and awkward. The femininity I tried to project didn’t align with how I looked. And that created a painful dissonance. In Morocco, even within the queer community, the more feminine your features, the more desired you are. That’s the unspoken rule. And I simply wasn’t that.

I hit puberty early. I was big, loud-featured, covered in body hair. I didn’t fit into anyone’s fantasy. So I tried to force it. I shaved, I dressed a certain way, I moved a certain way. I tried to become the object of desire. But no matter what I did, it never felt enough.

I turned to study. Not academics, but survival. I studied sex workers. I studied power. I studied how to control a room. How to draw someone in. I trained myself. Crafted a body, a language. Mastered the mechanics of seduction and used it to navigate danger, earn protection, and carve out small pockets of safety.

Photography by Zeid

I mimicked. I performed. I survived. Whilst in the middle of trying to develop a sense of existence in this system, I realized that it is a shared struggle with other queer individuals. I figured there was a collective disability rooted in us by design, meant to shut us down, to limit us from the start. The system overall was designed to suppress individuals, queer or not. But for the marginalized, the pressure was multiplied.

The system’s blueprint is clear: produce obedient people to serve corporations. Morocco is a giant firm in motion, marching toward an unkind capitalist direction. The ideal citizen is a function. A cog. To keep the capitalist wheel moving. There is no space to challenge the rules, no space to question tradition or conformity. So it’s even harder for queer people to exist, because our nature is everything that defies tradition and conformity. Thus, the system had to step on our necks harder. It had to apply more pressure. It forces us into submission, self-doubt, obedience, and disappearance.

We are made to believe we are sinners. Abnormal. Alien. And then we were expected to gaslight ourselves into heteronormative templates, only to be crushed under their weight. This is where homophobia thrives.

I cannot begin to count the number of homophobic individuals who bullied me, only to turn around and secretly ask me for sex. That’s when it clicked. These weren’t isolated contradictions, they were models. Successful prototypes of what the system produces: closeted, angry, violent queer people. Men who were never allowed to love or be loved honestly, so they turned their nature into rage.

And so I felt stuck in between maneuvering my way to survive among heterosexuals, and simultaneously, navigating queer spaces. I felt rebellious toward all of it, because none of it made sense to me. I decided to come out publicly. I wanted to tear down the mask. If I was going to take this battle, I wanted to do it without baggage, without secrecy, without emotional blackmail. I wanted to kamikaze my way through it, no more hiding, no more pretending, no more vulnerability to be exploited.

I took the biggest, scariest step: I came out to my very conservative family. And that step cost me. It came with pain. With physical and mental trauma. I was shamed and threatened, death threats. I was given two choices: renounce my queerness and return to Allah or face the consequences.

That is when I decided to run away from home.

It was emotionally taxing, yes. But I remember feeling proud. Triumphant. Even in homelessness, I had taken my freedom. I found places to crash. I hustled to eat, sleep, and live. I pushed through and finished high school. The autodidactic skills I’d developed during those earlier years became my survival kit.

I leveraged connections, harvested sympathy, and found just enough opportunity to keep going. The results were modest, but at the time, it felt like the biggest fuck you I could give to the system.

About a year after I had run away from home, I discovered that my parents were looking for me. They wanted to reach out and talk. Though their initial reaction had been harsh; driven by indoctrination and religious pressure, the reality of losing a child seemed to have changed something in them. So I met with them. I sat down and explained what it meant for me to be gay. That nothing had changed, except now they knew. That’s it.

What helped the conversation tremendously was my financial independence. They had never provided for me beyond a roof and food. Since I turned sixteen, I stopped asking for money, and they never gave any. This gave me leverage, especially because, power dynamics shift when you’re not financially dependent. It became clear to me how financial independence is vital for queer people: it gives us power in a system that’s designed to strip us of it.

I wasn’t asking for permission anymore. I was stating my existence.

And that made all the difference.

Navigating the dating scene in Morocco as a queer person is its own kind of chaos. On one hand, there’s me, openly gay and aware of the trauma we carry, the shame, the hookup culture, the dishonesty, the fear of vulnerability. These aren’t random traits, they’re symptoms of growing up in a system that tells us we’re wrong just for existing.

Perhaps, you can’t expect someone to be emotionally available when their entire life has been spent hiding. Most of us grew up without any real representation of queer love. I didn’t even know gay people existed until I was nine and accidentally found gay porn online, which, shocking as it was, felt like a confirmation of something deep inside me. I ejaculated on the spot. It was the first time.

My entire idea of love came from heteronormative TV and films. Not from my household; my parents never showed affection. So I entered my teens with no roadmap, searching for emotional connection in the middle of chaos.

The dating scene in Morocco is horrifying. There’s no structure, no healthy models, just trauma bouncing between bodies. My first romantic experience left me wounded and vulnerable. The emotional residue of that felt like a car crash, and I couldn’t function. At my age, it wasn’t simple to accept that I was denied the one thing I clung to as hope: love. The depression made me drop out of my first year of college, which coincided with COVID.

I found myself broken, insecure, alone. My brain sabotaged me with questions about my existence: why was I rejected by parents, society, and lovers? I started experiencing a form of psychosis. It felt like I was the problem. Was it my body? My face? My voice? My presence? Why did I get cheated on when I gave that person everything, my studies, and even my future?

It was during COVID that everything collapsed. Yet, somehow, my survival instincts kicked in. I started taking care of my body, working out, quitting drugs (or at least not accessing them). I found a creative outlet, where I began photographing my nude body and editing the photos. At first, it was about reclaiming confidence, then it became about visibility. I posted on social media. People praised me. I craved the validation.

That validation felt good, even if it came from a toxic place. I started oversexualizing myself online, creating pornographic content with a political edge: celebrating homosexual sexuality. I even launched an OnlyFans. It wasn’t typical. It was rebellious, shocking, and militant. And at the same time, I joined queer conversations. I connected with activists, collectives, and submitted my work.

When a Moroccan trans influencer publicly outed queer people by exposing their Grindr profiles, I was part of a collective in Rabat that responded to the crisis. It was my first hands-on experience with queer advocacy. I decided I wanted to keep going, to challenge the system, and use my voice.

By the end of quarantine in 2020, I made the decision to work with queer collectives. I wanted to channel my resilience, rebellion, and art, into something real. But to my surprise, when I started travelling around the country to meet queer people, groups, and advocates, I noticed how flexible it was. There was no real community, just cliques: the intellectuals, the Gen Zs, the sex workers, the mystics, and more. Everyone was divided, and nobody liked each other.

The worst part was learning that many of the donations meant to help queer people were misused for personal pleasure such as, parties, trips, and rituals based on superstitious beliefs.

Photography by Zeid

I realized the advocacy space itself was corrupted. Not all, of course, but enough to break my trust. Ironically, it mirrored Morocco’s larger political system built on fraud and power games. This further broke my trust, because I expected something different from queer spaces. We’re supposed to challenge corruption, not embody it. The betrayal from within felt heavier than what I faced from the outside.

Eventually, I spiraled back into the same coping mechanisms: parties, drugs, and sex work to afford it all. And that descent came with consequences. I made mistakes. I was abused. Exploited. And I ended up contracting HIV.

That was the cherry on top.

When I found out I had HIV, I felt crushed. Destroyed. Ashamed. I thought I had it all figured out. My first instinct was suicide. It felt like proof that I had failed. That my parents were right to shame me. That society would call me a dirty faggot and feel justified. The stigma is heavy here, even within our own community. Maybe especially there.

Among queers, HIV is the center of gossip. People get ruined. And I knew the moment I tested positive, my name would be next. I was terrified, not just of the virus, but of what people would say. I felt stupid for not being more careful. I had been open-minded about HIV before, but when it hit me personally I panicked.

At 21, with no income, no support, I had to figure out how to get treatment. A close friend who worked in an HIV association helped. The process was humiliating. You need tests like Western blot, blood work, and X-rays, to open a government case and acquire meds. It all costs money. You have to travel to Rabat. It’s slow, painful, and bureaucratic. Government workers give you dirty looks. Ultimately, they strip you of your dignity.

It took two weeks just to begin medication. And then the process repeats every three months. It’s draining. And to top it all off, someone leaked my status. Gossip spread like wildfire. People messaged me on Grindr calling me dirty and nasty.

That moment broke me. But it did not end me.

I came to realize that what I went through isn’t just personal; it was structural.

So many of us are carrying similar stories, similar scars. Yet, no one ever talks about it. Instead there’s this heavy, eerie silence, that hangs around queer existence. People are scared. Scared of being seen, of being known, that whatever safety or dignity they’ve managed to salvage will disappear.

We live in a system that was never designed for us. We are not educated about our bodies, our minds, our identities. Nor given space to question, explore, or become. There’s no sexual education, no mental health awareness, no emotional nurturing, no spiritual safety net for queer kids growing up here. You’re just thrown into the wild, expected to survive and conform.

The damage runs deep. Generationally and systemically deep. Still, nobody is talking, guiding, or asking the right questions.

I’m still carrying the emotional residue of everything I’ve lived through. I haven’t processed most of it. I don’t have access to medication that might help me calm my nervous system. I see power structures, manipulation, exploitation and my system shuts down.

So I hustle. I network. I survive.

But it doesn’t feel sustainable. It doesn’t feel safe. It feels like I’m hanging on by a thread most days. And I know I’m not the only one.

This is why we need to talk. This is why we need visibility. Not rainbow capitalism, not fake allyship, not online trends, but real, gritty, messy, honest conversation(s) about what it actually means to be queer and neurodivergent in a country that represses your existence. If you’re reading this, and you feel it, know that I wrote it with you in mind.

We are not broken. We were just never given the tools.

Yet, we are here. We’re still here.

And that matters.