Words by Niloofar Rasooli

Artworks by Tirdad Hashemi and Soufia Erfanian

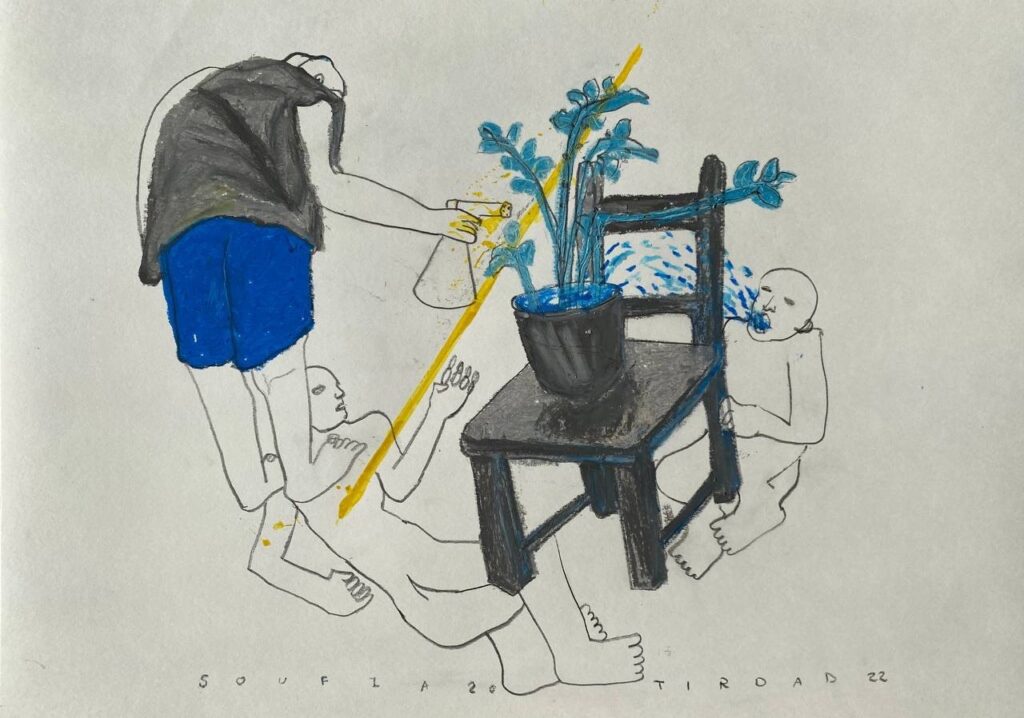

Featured image: Still wet with the shower of their treats, 2022.

This article is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

I was six years old when I wrote a story about a water well, khoshk o khali, dried and empty. The story was about a family’s dried-up water well and a single glass of water, magically found from somewhere. It was passed among its thirsty members, but no one were willing to drink it. The greater worry was the empty depth of the well, the family’s only material belonging: scarcity. The final decision was made: to pour the glass of water into the well.

Perhaps it was a magical well, one that received water and gave back more. They were desperate, or just curious. Hope made more sense, though it held no promise. When they poured the glass into the well, the burning earth vaporized the water. There was no magic, only the plain dictates of physics. The water well was empty and remained empty. The story ended there. Everyone remained thirsty, as did the well, khoshk o khali.

I titled it “A Very Sad Story.” I did not read it to anyone, nor did I write any other stories for a while. Instead, I performed poetry on the balcony to the wet clouds, which, at that point, I was convinced were God. My words felt like a spiritual responsibility, to make them cry and fill all the water wells around. They didn’t, not until I turned 17.

Water: something that spills and dries.

Water: something that moves through.

Water: something that is wasted.

I am 17 years old, and it is 2009, the Green Movement unfolds on the streets of Iran. National TV introduces me to a new word: Fitna. I recall hearing it in a different context, Zanan fetne be pa mikonnand, “Women stir up trouble.” Once a slur reserved for defiant women, the term now finds a new target: political dissent. Fitna. National TV is not funded to count the dead or the wounded. They tally votes, wielding numbers as proof against those making fitna. They have plenty of figures, graphs, charts, and splashes of color. Truth can be painted in pie charts. Their narrative plot moves city by city, village by village, summoning the downtrodden to declare their satisfaction with the outcome. They conclude the story by announcing it concluded, firing bullets, or driving over bodies in the streets, whichever works. It doesn’t matter. Fitna must be vaporized.

Water: something that gathers, hides, archives.

Water well: the thirsty soil and the things that had to return to it.

Water well: the closet of history, holding ghosts unwilling to come out or unable to bear the hiding.

I was six years old, and we never had a water well in our house in Zanjan. Apparently, it was never needed. Regardless, there was a constant collective desire to turn into that glass of water, spilled on the ground, evaporating, fading. After all, class is a matter of vaporizing, all that is solid melts into air. But many things don’t. The sweat of shame from empty pockets is sticky. My father’s forehead was always wet, as was mine.

Behind every arid moment, there may have been an attempt at dampness, a glass of water poured with intention, even if defeated by the sun’s harshness and the soil’s cruelty. But it was poured. It happened. It did. Wetness is resilience against fading, and we must remain engaged in the labor of upholding it.

Not all water wells are generous enough to vaporize. Leila, Joseph, my grandmother, and my mother, what unites them is their intimate relationship with water wells. None of them vaporized. My mother was beaten near one, while the others were hidden inside: Leila for love, Joseph for God, and my grandmother to escape the raping hands of Russian soldiers. When I wrote about that water well, whose generational trauma was I holding? Whose descendant was I?

The difference between an ocean and a drop of water is not determined by physics, but by their distance from the dead. “The sea is history”1, it holds all its bones close. A drop of water, however, must travel through the soil to reunite with its roots, a path too long for her to endure.

I am 17 years old, and it is 2009. Even God cries blood, and it makes me understand that it was not the water well that promised magic, but the streets. There is something magical about the streets in Iran. They receive blood but do not vaporize it. Instead, they give back more, more and more. But what happens if the gods cry for too long?

The communication between water wells and the sky has always been obscure. The sky does not always promise drops of water. It might mislead us, mistaking clouds for gods, drones for dead crows, and pellets for shooting stars.

I am 17 years old, and it is 2009. Like my generation, I stand on the precipice of an understanding: living within and through the erasure of memory. Sublimation. No liquids involved. The politics of forced forgetting seep into my generation’s consciousness like an insidious fog, a fog that solidifies the nerves. We learn that what we witness, what happens to us, what unfolds before our eyes, what we hear with our ears or feel in our hearts must remain as whispers, half-formed, barely spoken. We learn too quickly that our truth is deemed illegitimate, our reality dismissed as conspiracy, our lives reduced to fleeting, fabricated fiction. Our histories become like scabs, scratched and removed. We are called khas o khashak, twigs and straw, and our histories are labeled khoshk o khali. Some of us turn into water wells, dried, vaporizing. Some don’t. The new wounds grow over the removed scabs, promising wetness. Our fight becomes about upholding the wounds, keeping them wet.

“We once sought a cure in water, but water cannot bring back our dead. And so, we now turn to concrete tales for comfort.”2

I am 27 years old, and it is 2019. Still, things are about liquids, drops, fogs. The price of gasoline rises, as does the blood on the early snow of November. Mud, traffic, fire, snow, the smell of burnt tires, the silence of smashed windows. Newspapers humiliate the rage. Many die. We are no longer numbers. The pie charts vanish. Apparently, this time, there is no need to explain the numbers. Fitna never dies, nor does humiliating those in the business of fitna.

I am 28 years old, and the sky is still dripping onto the ground. This time, it is the bodies falling from an airplane, no one remains, only scattered pieces of flesh and memory. Bulldozers arrive before ambulances, scraping the burnt remains of life and history from the earth. Not a glass of water but an entire water well is filled with cement, leveling its surface with the ground, as if it never existed.

I am six years old, finishing perhaps the only story I could see having an ending, somehow knowing we would live through countless, never-ending endings.

Artwork by Tirdad Hashemi and Soufia Erfanian: The survival, 2022.

Water: something neither wet nor capable of making things wet.

Wetness: the impossibility of attachment, the touch between the vast, sunburnt body of soil and the daring dew that drops, digs, and dips, hoping to reach the still-living body of a burned tulip deep below.

I am 32 years old, and I belong to a generation born in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War, vaguely remembering the exiled survivors of massacres, names and numbers, mass graves, and chained murders. Raised amid the post-war shift in the state’s political economy, we spent our restless adolescence swept up in the first “big” political uprising in Iran after 1979.

Our history clings only to the fragile threads of what we can recall, captured in grainy, pixelated videos and photos taken, at best, with 3.2-megapixel cameras; shared over fleeting Bluetooth transfers; posted on abandoned Facebook accounts; anonymously uploaded to YouTube; and stored on fragile devices, doomed to decay with time. The spaces we once claimed, the streets we sprinted through in a single breath, the alleys where we sought refuge, the hands we clasped, the pamphlets we passed around, the defiant blaring of car horns, have dissolved into ghostly outlines of vanishing unrest. Dried.

Wetness: a delicate branch of a plant, sprouting in the wrong season, breaking into a sweat at the sight of snow falling.

Is intergenerational memory like a damp cloth, absorbing fragments of blood, sweat, and tears from many ghosts and souls, leaving faded stains of what once was burning liquids? Or is it more like the bottom of a well, which either swallows us at the end of our story, returning to violent dryness, or temporarily holds a space of refuge? Is dryness a trace of wetness, and wetness of drops of water, and water of the sea, and “the sea is history,” holding death dearly? My return to a fragment of a story I wrote at the age of six is, above all, an attempt to understand the reserves left behind by intergenerational stories of scarcity, absence, impossibility, and desolation, to recognize that dryness is fleeting. Behind every arid moment, there may have been an attempt at dampness, a glass of water poured with intention, even if defeated by the sun’s harshness and the soil’s cruelty. But it was poured. It happened. It did. Wetness is resilience against fading, and we must remain engaged in the labor of upholding it.

Wetness: sweating.

Wetness: dews of memory.

Wetness: ungraspable traces of fading pasts.

Wetness: remembering.

I am 29, and it is 2022. Our stories always seem to begin in the middle of unfinished ones. Layers pile upon layers, the violence grows heavier, and the faces we once knew blur into the backdrop of what we now endure. Fog is our archive. To narrate in the dusty fog, we are forced to weave our own narratives, carving them into the wells of history with fragile nails. Water well. We dig, clawing to etch our story, tossing the only glass of water we have into its depths, only to watch it vaporize, vanish, and then we dig again, we pour ourselves there, repeatedly.

I am 29, and it is 2022, the Jina Uprising. Water wells are filled, surpassing their limits. The wetness of many drops turns into a flood, daring to seek the sea, yearning to reach it. We drink from the water wells of our mothers and sisters. We do not vaporize, khis o por, wet and full.

I am 32 years old, and I will never be six again, that is the unfortunate reality of linear time, nor do I wish to rewrite the story I wrote back then. I no longer confuse clouds for God, but I might still perform poetry for them. Now that I can afford to fly in airplanes, passing among the clouds, I am still surprised that they are not as solid as I once believed. The difference is that I finally read the story to my mother. I only want to know why I knew about the water wells before her telling me about what had happened around them, to her, to her mother, and to so many others.

What of these wells? What of the women who stood at their edges or were thrown into them? What of their songs and silences? And what of us? What will happen to us? “Maybe you heard about it when you were in my womb,” my mom says, laughing sweetly. “Is it possible?” I ask her. “Everything is possible in the womb, it is made out of water and blood, the sources of life,” she says, still laughing, hearing me take a six-year old’s story too seriously. “Also, I remember seeing you performing something to the clouds, I never wanted to disrupt you, you were too serious.” I hold no wish but to float in that laughter, or in her womb, one more time.

The womb: khis o por, wet and full.

The womb: a water well passing the wetness of memories, dripping into the life that emerges from the water and blood.

- Dionne Brand. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. (Doubleday Canada, 2002), pp. 11.

- Jumana Emil Abboud, ‘Hide Your Water from the Sun: A Performance for Spirited Waters’, in War-torn Ecologies, An-Archic Fragments: Reflections from the Middle East, ed. by Umut Yıldırım, Cultural Inquiry, 27 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2023), pp. 121–38.