Words by J.D Harlock

Artworks by Qaduda

This piece is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

Note on the word “sheikh:”

In Lebanon, sheikh is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning “Elder.” It’s used to refer to the political elite and their male descendants, or in other words, what the children I went to school with will be called one day.

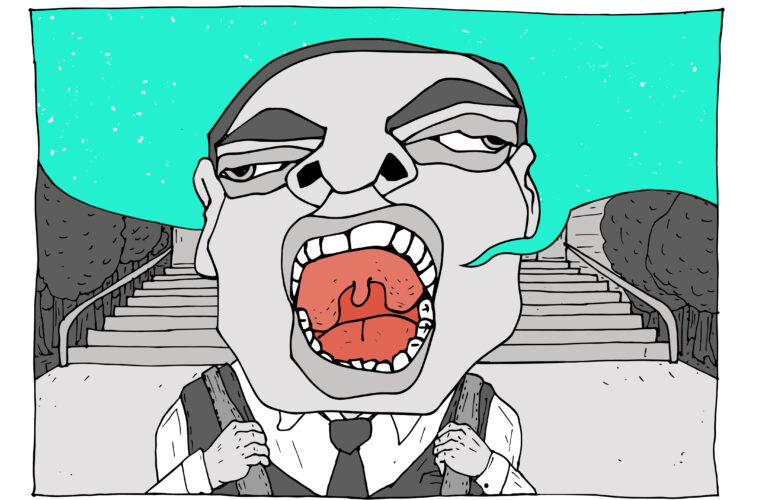

Political discourse in Beirut is infamously volatile. It’s loud, aggressive, and in your face wherever you go, which is to be expected because, like every other pissing contest in Lebanon, it all starts in the playground.

It doesn’t matter which kind of school you go to, and it doesn’t matter where. You’ll always find students running around in packs, itching for a fight, flinging slogans and hurling chants, hoping that cliques of opposing parties pick up on this and start a scuffle. It will get ugly. It will get violent. Nothing will be learned. And after the administration forces everyone to make up and shake hands, the students will be right back at it by the time the next recess bell rings.

Ironically, Lebanon is also known for its relatively progressive religious plurality represented across economic and political spheres. Its parliament allots a certain number of seats to specific sects, and since politics here is split along sectarian lines, that means that each of the major religions has formed its own party with exclusive networks that selectively allow cronies from their “kind” to enter. With eighteen different denominations recognized in our political system, and multiple political parties pretending to represent them, the reach of these organizations is unlike what other countries will be familiar with. Regardless of background, it seems like everyone you know has some kind of connection with the political elite. Maintaining these connections has become necessary if you want to navigate the system. Survival is contingent on doing whatever needs to be done to appease the sheikhs and their entourages.

Even though the “enlightened” among us understood how superficial and artificial the sectarian clanning and shouting matches were, it ironically prepped us for the political soundscape of the real world. We were taught what discourses we were to accept and from whom we should accept them.

Unsurprisingly, the power has gone to their head. Nowhere is this on clearer display as it is with their children, who will remind you of how grateful you should be for whatever of their sloppy seconds trickles down to you, and how thankful you should be for their protection from whatever “other” they wanted to demonize that day. By the time these little sheikhs come of age, their philippics1 are turned up to eleven. Every political discussion in our universities will start this way. Yet somehow, it still comes as a surprise when we find out that a free-for-all has broken out on university campuses and local law enforcement has to intervene. Not that it’s any surprise to anyone who actually attended a school here.

Back in my day, school administrations claimed to clamp down on these kinds of firebrand stunts lest all-out brawls break out on school grounds. However, their priorities seemed more oriented towards appeasing the parents of those who were responsible for these all-out brawls. And so, with little-to-no intervention from the adults in the room, the screaming matches of the talk show heads and the standup routines of our sketch comedians were readily reenacted in the classroom. Students stood up on their desks as if they were podiums and serenaded us with their curse-laden impressions and their parents’ questionable hot-takes. Teachers barely put up the pretense that they couldn’t understand what they were hearing, and would practically pretend to be deaf so as not to involve their higher-ups.

Forced to listen to this daily, even the soundless-ness of the little sheikhs became deafening. Moments of quiet were just pauses in their never-ending tirades against any developments in the political scene, and during the aughts and early New Tens, there were a lot of them. It was only a matter of hours until something happened to have them blasting their colorful commentary again, and there was nothing to do to stop it. The silence of the teachers and “non-elite” students then became suffocating; we’d inherited our elders’ need to keep things hush-hush. Imposed on us through threats and intimidation, the squawking of the children of the elite not only quashed dissent, but it organized us into hierarchical social structures of their choosing. Friendships were dictated by political alliances, and interparty allies coalesced in social circles whose chorus drowned out dissenters. Even though the “enlightened” among us understood how superficial and artificial the sectarian clanning and shouting matches were, it ironically prepped us for the political soundscape of the real world. We were taught what discourses we were to accept and from whom we should accept them.

Artwork by Qaduda

But the behavior of these little sheikhs is unsurprising. Born into privilege and tutored from an early age to what passed as politically literate in these circles, their words were imbued with a sense of potency and legitimacy that we could not channel for our own beliefs. For the “non-elite,” particularly middle-class families or old money dynasties, parents knew nothing of politics; it was justifiably associated with brash buffoonery. Or, they kept their political opinions to themselves, fearing that their children might upset the wrong people.

The resulting silence seemed reasonable to us when we didn’t understand the consequences of holding out tongues, which acted as a form of tacit approval that emboldened the shrieking sheikhs to screech their creeds even louder. Their “prestigious” political backgrounds positioned their voices as an authoritative one. In tone and tenor, confidence was imbued that not only gave their voice a presence and amplified it but legitimized the nonsense that indoctrinated us.

Back home, it was difficult to communicate the problem with my family. I had trouble articulating what was wrong. I was not politically literate at the time, nor was I familiar with the regional sociocultural and local sectarian dynamics behind the machination of the political elite. I didn’t have the words to properly explain what was happening in our classes and our playgrounds. To my family, it just sounded like regular old roughhousing between rowdy teens. Other students seemed to think that was the case too, insisting this is what life is like here, what it has always been like, and what it will always be.

I was on my own. Many of us had to respond to the accusations of hidden agendas and international espionage that these sheikhs readily chucked at those who disagreed with them, or, in my case, handle the silent disdain they directed at those who were not worth their energy. I honestly had no clue what they were shrieking about – outside of issues like the environment or LGBTQI+ community – and I found it overwhelming to try to understand the politicking of this particular shit storm, let alone to clap back. You couldn’t just call out their lies; you had to have the fluency to talk their ears off.

Because, on the playground, if you don’t scream your lungs out, then you’ve effectively lost the argument.