Written By: Bo Hanna

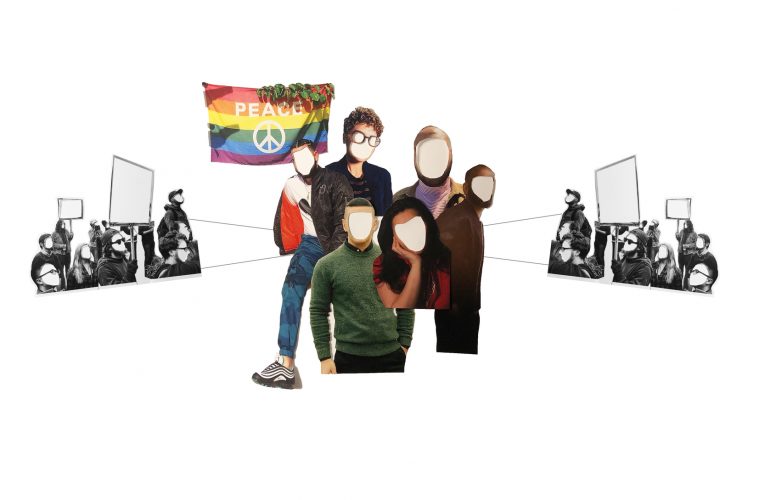

Art work by Yasmine Diaz

Copy edited by Eliza Marks

As the conversation about LGBT rights globalizes, LGBT people of Middle Eastern descent have become increasingly caught in identity politics in both the MENA/SWANA region and Western multicultural societies in which different minorities coexist.

The contemporary discourse that qualifies what is “Western” and “non-Western” has only intensified these politics. Extreme-right political parties in the West claim LGBT rights, women’s rights, and sexual liberty as fundamentally Western values that lie in stark contrast to the values of ethnic minorities that not only do not support but also threaten these beliefs.

At the same time, governments around the world, like in Brunei, Chechnya, Azerbaijan, Indonesia, Uganda and Egypt, bolster their moral legitimacy by cracking down on challenging bodies like LGBTQ peoples and female popstars who publicly push social norms via protest-video clips, politicization, or by publicly engaging issues ranging from pollution to gender. For instance, human rights activists in Egypt say they are witnissing the toughest crackdown on the LGBTQ community and women artists in decades, as is exemplified by the persecution and detention of a growing number of female artists over the past three years, including Shyma and Sherine Abdel Wahab, and the events that followed concert goers waved rainbow flags during a 2017 Mashrou’ Leila concert. The Lebanese band was banned from performing in the country. The band was similarly banned several times in Jordan because the band’s songs ‘would contain lyrics that do not comply with the nature of Jordanian society,’ according to the Amman Governor.

Despite this, people in the MENA region are finding ways to speak out against homo- and transphobia with the help of local activists and artists. At the same time, queer people of Middle Eastern descent living in the West who are encouraging people to love whom they want to love and be themselves. This, however, forces them (LGBTQ activists in the West) to face ostracisation from the communities they left, accusations of conforming to Western values (and betrayal of regional norms), potential exclusion from engagement with regional issues, or discreditation as activists.

I have faced a number of these problems myself as a queer man of a Coptic-Egyptian descent living in the Netherlands, both in the Dutch LGBTQ community and my ethnic community. I am part of by two minorities that seem at odds, and, perhaps as a result, I feel stigmatized within both and am constantly trying to balance in between them. For instance, LGBTQ people in the Middle East reacted both positively and negatively when I started writing about identity politics and my queer Arab identity; some queer peoples thanked for making their struggles visible, but others told me I was not able to relate to their struggles because I mostly grew up in the West.

I reached out to LGBT people of Middle Eastern descent and activists living in the West, and spoke of their challenges they face moving forward.

“The struggles I face in the West are not because of my queer identity. They are merely caused due to my ethnic background.”

Activist Dalia Alfaghal (29) faced a viral backlash for publicly announcing her lesbian relationship on social media when she lived in Egypt, before moving to Sweden. Dalia continued being vocal about the oppression she faces but is being criticized by other queer activists living in the MENA.

I represent myself and my personal struggles. I have been an immigrant in Saudi Arabia, the USA, or Europe. I didn’t go there because of my privilege alone; I worked hard to get to where I am now. Despite this, I have been attacked by self-proclaimed ‘radical’ queer activists in the MENA, an argument based on the assertion that I don’t represent all the LGBTQ individuals. This critique is true: I don’t represent the community, I represent myself and my journey. I also get attacked by (radical) queer activists in the MENA who tell me I cannot relate to them and their struggles. The above is rooted in my perceived privilege, but we cannot simplify privilege to a specific set of criteria. I know queer people that live in Egypt in progressive families and get to be who they are, and other queers in the West who grew up in conservative families and don’t get to be themselves, sometimes even face death threats. Fortunately, I also get positive reactions from queer people in the MENA region who perceive my presence, in contrast to the aforementioned critique, as powerful and inspiring. We should focus on addressing the issues we face instead of fighting the queers who receive attention. We all deserve to been seen and heard.

Samer Owaida (22), a Chicago-based activist born in Palestine, echos and adds depth to the complexity of privilege that Dalia described through describing his own experience in America and how his work is received.

Being queer and marginalized is a global issue and I think some cultural ideas about gender and sexuality follow us to the West. I live in South-West Chicago, also called ‘Little Palestine,’ which is highly religious and conservative, and didn’t make it easy for me to be openly queer. It’s an illusion to think you’re completely free once you move here [to the West] you will have a fantastic queer life, because of, for example, gay marriage. There is still a lot of violence against queer bodies in the USA, as seen in the high rate of homelessness among queer youth and murder trans people… In the end it’s all about class. In a country like Lebanon, queer people can avoid state violence if they are from a certain class. In my neighborhood, my social media posts brought me, and my sister by association, hard times. Fortunately, I get a lot of positive reactions from both LGBT people in the MENA region and in the West thanking me for making our struggles visible… What motivates me is my love for my people – we should stop wasting our time by arguing and devaluing each others struggles and unite and fight for our rights.

Mena Kamel (31) is a first generation Egyptian-American writer and visual artist from California and founder of Coptic Queer Stories, an online magazine covering gender, sexuality, race, and religion that aims to record the experiences of Coptic LGBTQ+ individuals in the Coptic diaspora. Kamel places his experience in broader structures of power, claiming that queers of Middle Eastern descent in the West are confronted by marginalizing forces that many other queer people of color also face, including racision and fetishization.

My queerness is not separate from my North Africanness is not separate from my maleness is not separate from my atheism is not separate from my Americanness. While we might share some history and heritage with queers in the MENA region, it’s important to identify what our cultural commonalities are. Cultural influence doesn’t only define the parameters of any given political movement, it also contextualizes it and its progression. Since we share some cultural commonalities, we might be able to recognize or imagine these issues within our various diasporic cultures. But,can we identify with SWANA region queers and their actual struggles? I’m not sure. There’s a relationship, however, and that relationship can be complicated at times. That said, it doesn’t mean we cannot lend our support in a variety of ways or offer strategies on what works and don’t work for those of us who are outside the region.

Queers of ethnic minorities in the West, and especially queer Muslims, are forced to negotiate about their position between being queer or their culture. Thee-Yezen Al-Obaide (34), who was born in Baghdad but fled with his family to Norway 18 years ago, said that,

I see similarities between my struggles and the problems queer people in the MENA region face. But I think, at least in Europe, it’s more an identity matter, while queers in the MENA region deal with persecution, state violence and legal rights. In Norway, I have the feeling like I have to choose between being queer or Muslim, you cannot be both without being stigmatized from both sides – homonationalism is a serious thing in Europe.

“Being queer and marginalized is a global issue and I think some cultural ideas about gender and sexuality follow us to the West.”

Amir Ashour (29) is the founder of IraQueer, one of Iraq’s first LGBT+ organizations focusing on education and advocacy. He was born and raised in Iraq till he was 24 years old, and now lives in Sweden, where he was confronted with racism and discrimination against refugees.

Personally, the struggles I face in the West are not because of my queer identity. They are merely caused due to my ethnic background. I believe racism is a problem Sweden suffers from. The resources provided to refugees are nowhere near the resources provided for others which puts us at a disadvantage. At the same time, I have lived through the discrimination and violence in Iraq, was imprisoned twice, and I have received threats from multiple groups. I’ve been attacked by my own friends, and no longer have connection with any of my extended family. Just because I live in the West, it does not mean that I no longer face the discrimination or that my 24 years in Iraq have been erased. I think it actually allows me to see what’s possible and work to achieve that in Iraq, but this might be different for someone who was born and raised in the West and has never lived in the MENA region. I am not saying their contribution is not valid though, but we need to realize that our role is different than the role of queers that in the MENA region. At IraQueer, I am more the public face. I do advocacy internationally, meet with governments, do fundraising, and other tasks that require more visibility. But my colleagues in the ground do documentation, reporting, and make sure the LGBT+ community is constantly telling us what the needs are, and what our projects should focus on.

It is imperative for one to consider their position in advocacy might shift due to experience or geography, and the different needs of queer communities of Middle Eastern descent in MENA versus the West. Amsterdam-based Nour Anne Abdullah (41) from Kuwait also moved to Europe 6 years ago because of her gender identity, but still helps international LGBT organizations from a distance.

Many LGBT people leaving the MENA region suffer from PTSD and are traumatized by state violence. The difference is that in the West, the government will protect you if your family doesn’t stand behind you, while queers in the MENA face violence from both their family and the government.

Despite being subject to similar cultural codes, it is clear that the struggles of queers of Middle Eastern descent in the West differ from those of LGBT people in the MENA region. Queers of Middle Eastern descent in the West face similar struggles to other people of color there, including racism and fetization, and are forced to negotiate their position in terms of their queerness and their culture. Queers in the MENA region might not relate to these issues, just as queers of Middle Eastern descent in the West might not relate to the issue of state violence that queers in MENA face. However, even though our narratives might differ, activists from both groups resonate with people all over the world and should continue speaking to each other working to make their communities and the broader MENA region a brighter place for queer people.