(Link to submission form)

Deadline December 16, 2025

Art today does not arrive from distance or safety. It moves through bodies under pressure, through streets under surveillance, through networks that absorb, distort, and sometimes silence it. It is made under conditions where time is stolen, futures are withheld, and families displaced. My Kali magazine’s next issue begins from that reality: art not as commentary on crisis, but as something formed inside it.

We turn towards practices that carry the weight of real consequence. Works made where visibility is risky, where speech costs, where memory itself is contested. These are not representations of struggle, but forms of art shaped by it, by occupation and displacement, by censorship and capital, by gendered violence and the daily labor of staying alive.

Our editorial and creative team selected references for this issue. Keep in mind that these do not function as answers, but as examples. They show how art intervenes, resists, and imagines otherwise, across time and geography. From Youssef Nabil’s quiet, aching portrait of the Tunisian singer Zikra, an artist whose life and death remain suspended between rumor, patriarchy, and governmental power, to Yasmine Hamdan’s icy takeover of Beirut’s streets and newsrooms in music video Balad, where frustration becomes performance and spectacle becomes accusation.

From the early revolutionary cinema of Mustafa Abu Ali in Scenes of the Occupation from Gaza (1973), where the camera itself becomes a tool of defiance, to the raw insistence of Arab Loutfi’s Tell Your Tale, Little Bird, which restores Palestinian women guerrilla fighters to history after decades of erasure. From Heiny Srour’s Leila and the Wolves, which ruptures colonial timelines through a feminist time-traveling gaze, to Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project, where hands trace routes the state was never meant to witness.

We look to practices that confront power through satire and provocation: Safie Eddeen’s circulating emojis and Ramy Essam’s song/music video Balaha, both and Ramy Essam’s song/music video Balaha, both of President Sisi, where ridicule becomes a strategy of survival; Sinead O’Connor tearing the Pope’s image live on television in 1993 after her performance on SNL, collapsing spectacle into rupture; My Kali’s own photo-essay/feature on director Widad Shafakoj titled Label Protest! in Hay Al-Qayseyyeh, where luxury logos sprayed on crumbling walls in Amman, expose the violence of class transition, government tax hikes, and urban gentrification.

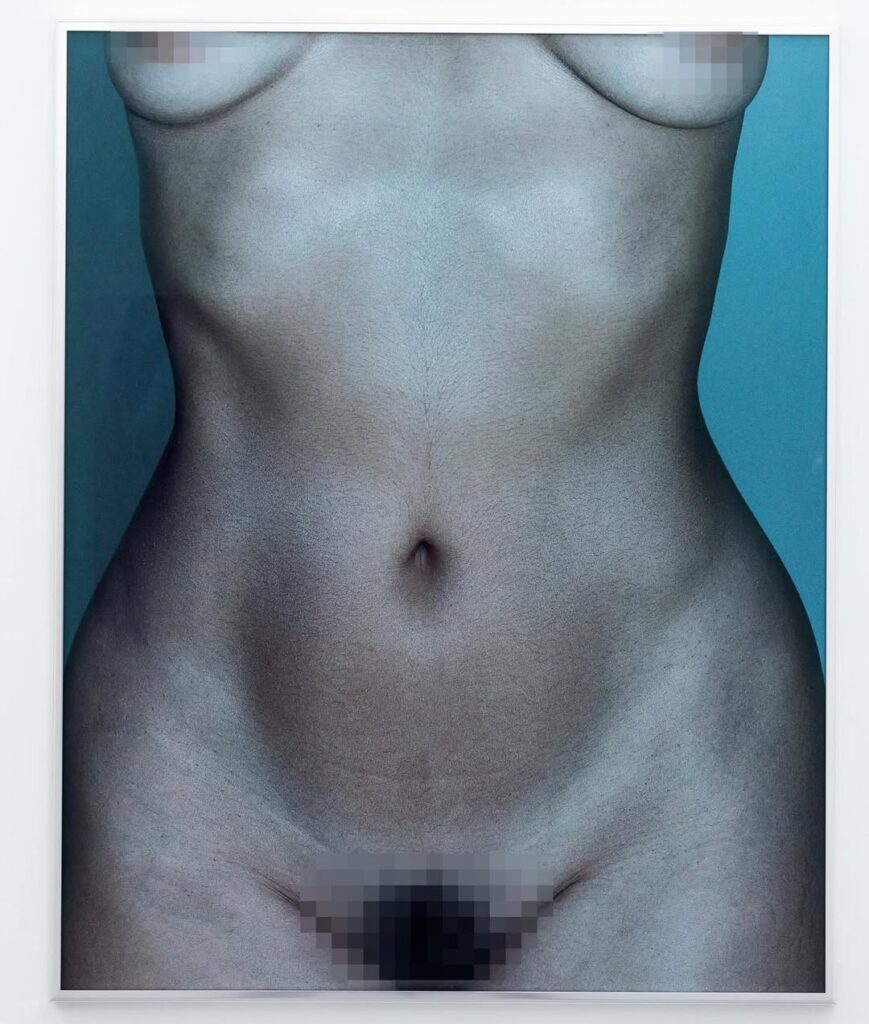

We look to bodies as sites of struggle and medium: in Mona Hatoum’s Keffieh, where hair replaces fabric and gender, nation, and desire entangle; in Yumna Al-Arashi’s photo-post on instagram, reclaiming that “my body is political,” where survival itself becomes a daily act of resistance; while Mohammed Soueid’s documentary portrait of Khaled El Kurdi, a Syrian trans woman living in Beirut, back in 1993, captures an intimate defiance in Cinema Fouad, where domestic space becomes a shelter from a hostile world.

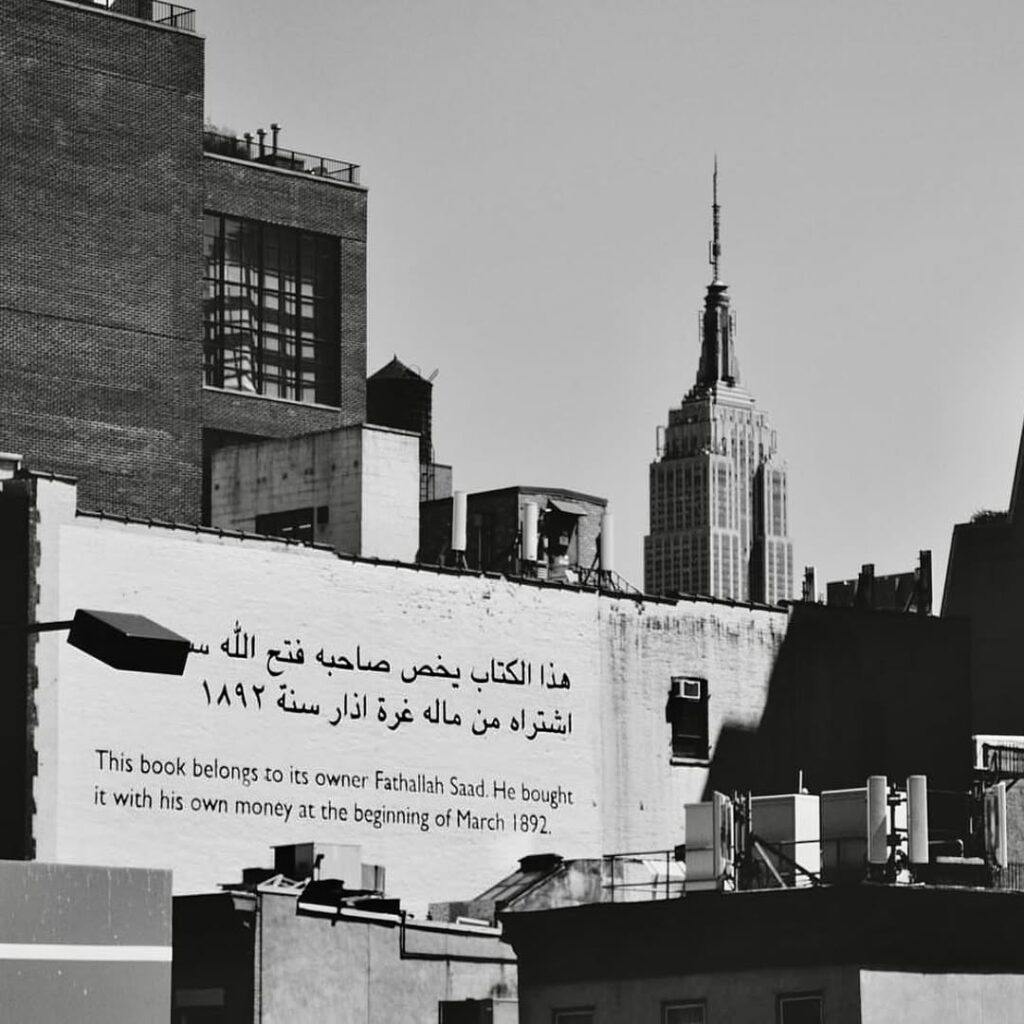

We look to memory under siege: in Emily Jacir’s Ex Libris project, which insists on the return of looted Palestinian books as a fight against historical erasure; in Bahia Shehab’s graffiti, from Cairo walls to the defiant Blue Bra murals during the Arab spring in 2011, where public surfaces become a forum of resistance, transforming shame, censorship, and violence into messages of collective memory and solidarity. We look to the media itself as a battleground, in Writers Against the War on Gaza’s The New York (War) Crimes, which exposes how narratives of war are manufactured, sanitized, and sold back to us.

Together, these works ask not only what art represents, but what it does: how it records when archives are destroyed, how it speaks when speech is policed, how it gathers when assembly is forbidden, how it imagines when futures are foreclosed and imagination is policed.

For this issue, we invite submissions that treat art not as decoration or metaphor, but as a practice of disruption, as a tool for witnessing, surviving, remembering, and re-worlding. We are interested in works, archives, gestures, and experiments that emerge from within struggle and refuse the comfort of neutrality and commodification

This is an invitation to think with us, to swim up the stream: to look closely, to reference widely, and to expand to an art capable of confronting systems profiting from death, extraction, and erasure.

(Link to submission form) – Deadline December 16, 2025

Reference Constellation

Youssef Nabil, My Friend in the Skies – Zikra, 2000 — A portrait haunted by an unresolved death, patriarchy, and the violence faced by women artists.

Mustafa Abu Ali, Scenes of the Occupation from Gaza, 1973 — Revolutionary cinema as counter-archive.

My Kali / Project: Manifesto, Label Protest! — Class, gentrification, and the violence of luxury. Here Widad Shafakoj Photographed by Agnes Montanari.

Yasmine Hamdan, Balad, dir. Elia Suleiman, 2017 — The citizen as performer of dissent.

Safie Eddeen, Sisi Emojis, 2016 — Satire as survival under authoritarianism.

Sinead O’Connor, SNL Performance, 1992 — The moment dissent shattered spectacle.

Laila Shawa, Where Souls Dwell, AK47 series — Weapons turned into sites of artistic refusal.

Myriam Klink, Klink Revolution, 2012 — Pop provocation amid political collapse.

Yumna Al-Arashi, “My body is political” — The body as archive and battlefield.

Heiny Srour, Leila and the Wolves, 1984 — Feminist time-travel against colonial history.

Emily Jacir, Ex Libris / Fathallah Saad, 2014 — Cultural theft and the fight for memory.

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–2011 — Migration as testimony.

Mona Hatoum, Keffieh, 1993–1999 — A national symbol undone and reconstituted through the intimacy of hair, where adornment becomes exposure and gender slips through the fabric of resistance.

The New York (War) Crimes, WAWOG — Media as a site of confrontation.

Bahia Shehab, Cairo graffiti, 2011 — Street as collective voice.

Ramy Essam, Balaha, 2018 — A viral protest song that weaponizes satire against the cult of the strongman, transforming pop mockery into a direct confrontation with state power and exposing how ridicule can fracture authoritarian spectacle.

Laila Shawa, Disposable Bodies 4 (Shahrazad), 2012 — A violent collision between Orientalist fantasy and contemporary warfare, where the archetype of Shahrazad is overlaid with the iconography of terror, exposing how Arab women’s bodies are repeatedly aestheticized, eroticized, and rendered expendable under empire. Shawa’s work combines sensuality and the aura of threat, it suggests the value(lessness) of feminine lives in a patriarchal society that demands purity and conformity of women.