Words by My Kali Magazine

Photography by Malak Kabbani

Creative direction by Youssef El Sayed

Styling by Zahra Asmail

Makeup by Chiharu Wakabayashi

Hair by Masayoshi Fujita

Photo treatment & typography by Hussein Salem

Photo assistance by Taha Izzi

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

British-Lebanese powerhouse, music producer and DJ Saliah, emerged from the drum & bass rave scene in London. At 15, she was mixing vinyls at friends houses, and soon thereafter, landed her first DJ gig. Today, she’s known for her cross-pollination of Arabic pop with UK sounds. Since her legendary Boiler Room debut in 2022, she has sold out every headline show, set a new record at venues hesitant to have all-female lineups, and continues to work behind the scenes on diversity and inclusion in the industry.

We first caught up with Saliah over coffee in London last January, as she was gearing up to play her last headline shows of 2023 after being on strike in protest of the war on Gaza since October. With the war still raging, and the world growing increasingly polarized, things take on different meanings. As venues cancel shows and alienate artists over the expressions of support of Palestinian liberation, parties no longer resonate as mere strings of euphoric moments, but become expressions of our presence, rage, our sense of community.

Let’s begin with your name, Saliah. Is there a story behind it?

Mama wanted to call me Sally, after a Japanese [TV] show that was translated into Arabic and really popular in the Arab region. But it’s also a fairly common name in Lebanon. My Jeddo (tr. grandpa was insistent that – because my last name is a white, Western name – there was nothing to say that I was Lebanese. He suggested Saliah. There’s no meaning behind it, other than preserving the heritage.

I feel like there’ve been some really full circle moments in connection with my Jeddo. He raised nine children with my Tata, and my mum said he never held any of the grandkids. When I was born, he held me all the time. We lost him when I was only five years old – he was at home in the south of Lebanon, when he collapsed from the shock of a bomb that went off nearby during an Israeli bombing campaign. We then discovered he had cancer, and he passed away pretty quickly after. There is something in the fact that I am now international, with my name, that’s linked to him. I feel like there is a calling to it, because he’s the one who wanted me to be strong in my identity.

You first started DJing in the drum & bass scene. How did it all start?

I was part of the UK rave scene from 2005-2018. At that time, the drum & bass rave scene was huge here in the UK. It still is, but back then it was even bigger. My group of friends was interested in it, and when we hung out after school, we’d go to someone’s house that had a pair of turntables, bring our vinyls and mix together, trying to out-mix each other.

I’ve always been DJing on the side since I was 15, and I got my first gig when I was 18 and carried on for 10 years. I took a year and a half hiatus and traveled, and then I got myself a controller. That opened me up to mix with lots of different genres because I had access to more digital stuff, rather than using analogue. And, I was experimenting with Hip hop and Arabic and stuff. It was only about 3 years ago that I started to produce my own music.

Technology changed drastically in those ten years… It was a massive shift. When I started, there wasn’t such a thing as CDJs. We had to learn how to switch from vinyls to CDs and then to USB.

Photography by Malak Kabbani, Photo treatment by Hussein Salem

You were trained as a graphic designer. How does this integrate with or influence the way you make music?

I describe myself as a “creative practitioner for social change.” I was freelancing for most of my life, and I would specifically work with companies that were doing something with a social impact. I really wanted to go into “service design,” which is where you design services for communities, and was always heavily involved in this kind of thing. I was creating art projects to raise money or awareness of some kind (the humanitarian crisis in Syria, the Kafala system in Lebanon, etc.)

This changed at the beginning of 2023 after the Boiler Room was released. I had no choice but to drop graphic design and go full-time. I’ve been on international tour since January [2023].

Can you say more about how this Boiler Room show was a turning point?

Every time I perform, I genuinely believe this could be my last time. I really care about the experience that people have, because people come from different countries to come and see me… it’s crazy. I really want to put out what I want to receive in this world, and not get arrogant. The music industry is so messed up, it’s so full of ego and gatekeepers. I want to dismantle that.

With the Boiler Room set, I thought this might be the only opportunity to share what I do. I worked so hard; I practiced for hours, I thought about every transition with so much precision and detail, I edited every track to make sure I could get that many in an hour. I also produced 5 of my own tracks for that set because I wanted this to be a pivotal moment, something that would be archived as a statement, as a story, as a narrative. I thought, why not show the range of what I can do, starting from Hip hop and finishing on Drum & Bass.

It told a story about my life journey, my identity, and “us.” It had elements that touched on the historical, like Warda’s Batwanes Beek. These things that were important to showcase. I wanted to create an experience like a Mawal, that starts slow and rhythmic and builds into something joyful. And then having a shock-factor drop by incorporating Western sounds – that’s the vibe I wanted.

Can you say more about the feedback or reactions you received, and how you felt about it?

It’s crazy! Obviously, the crowd favorite was “El Hantour.” I’m now slightly fed up with it because I play it every weekend, but when I see people’s reactions, I fall in love with it again. I think this was one of the first ever UK-Bass remixes of an Arabic song, and I feel like I’ve inspired a lot of people to try to create Arabic remixes and styles of mixing.

I’m really trying to introduce this UK sound, but a lot of people mistake it as techno. In Egypt, people thought that I was going to do a techno set because, in our region, people think anything with 135 to 140 BPM, with kicks, snares, and high hats is techno. One female producer friend was like, “I don’t even know, everything for me is techno.” I agree that we can be genre-less, but there is also a history to genres – each has its own context.

Growing up between Kuwait and the UK, you’ve been exposed to a mix of cultural influences.

In Kuwait, we were very heavily influenced by American Hip hop because after the Gulf War, Americans were kind of hanging back, as they do [she laughs]. Kuwait was like a melting-pot with so many cultural influences, especially from African and Indian cultures. One of my favorite bands growing up was Miami Band, an Afro-Arab Kuwaiti band that incorporated a lot of Brazilian samba in their songs. I listened to them more growing up than I did Lebanese music or sha’abi, and that attracted me to different sounds.

When we moved to a really White area in the UK, I felt so disconnected from our [Arab] culture. The community I felt most connected to was the Black community, which contributed so much to the British music industry, to the point that it couldn’t have existed without this contribution. Black-British artists draw very heavily from their roots, whether that be from the Caribbean or from the African continent – you can hear that in Sound system (Jamaican) culture, which is huge in the UK. These influences changed my perspective on music.

You’ve been touring all over the world, do you tailor your sets to different audiences?

In every country I play in, I try to include a sound or a song that the locals would feel connected to. I try to bring in these elements in playful and unexpected ways, because my mixing style is about the shock factor, and I’m always adding new remixes that I work on between performances. I view crafting shows as producing a performance rather than just DJing.

Have you had to deal with censorship in any of these contexts?

I had to deal with censorship in some countries. For example, once I wasn’t allowed to perform wearing my jalabiyya. The organizers said it might cause an issue, and then the police literally said it’s not happening. It’s because I’m a woman – a white guy came and played in a jilbab the week before.

The jalabiyya has such a strong message. I relate to it from a Khaliji perspective, not a Lebanese one. So many Lebanese and Egyptians were like, hatha shi lel beit (tr. “This is something to wear at home”), but from a Khaliji perspective, it’s something you wear lel 7aflat aw lel 3ares (tr. to parties or weddings. You dress up in a bedazzled Jalabiyya.

I feel like I’m in drag when I wear it, and like I’m almost my own superhero. In the context of me performing, it represents something that is freedom or liberation from our patriarchal society. And, it gives me so much strength and confidence, like I’m telling the world so what, we can do things that we’re not expected to do as women. This juxtaposition is so powerful, and it’s stunning how many women show up at my shows – I think they feel safe. The jalabiya I wore in my Boiler Room set has become iconic, and I have a tradition of wearing it the first time I play in a new country.

Photography by Malak Kabbani, Photo treatment & typography by Hussein Salem

You’ve also contributed to a lot of community based projects, including Future Female Sounds, Saffron Records, Haven for Artists, and others. Can you say more about this?

I think a lot about the legacy that I want to leave behind, and I don’t think that I had a lot of role models for myself, as a woman, and especially as an Arab woman in the DJing industry.

At some point, I had a big disagreement with my mentor – to give context, he’s a cis-Arab male. During one of our first conversations, he said, “I’m ok with female DJs, but the problem is that they don’t bring their A-game.” Don’t get me wrong, he is super supportive and acknowledges why what he said is problematic, but this language is a reality for a lot of women in the industry. As Arab women, we have so many obstacles. We’re not afforded the privilege of play, we’re not afforded the privilege of “a3meli eli badik yah” (tr. “do as you please”)… we have to fight even harder to bring our A-game.

Now it’s probably better, but when I was coming up in the music industry, the amount of sexual harassment I faced was ridiculous. Once, I asked a DJ on a popular radio station in the Drum & Bass scene if he had any unreleased tracks that I could play, and he responded, “If you send me some nudes, then I’ll send you some tracks.” These things happened so often. Sometimes, I would literally watch men change as many settings as possible before I came on, because they really want you to mess up. And, for women, there are so few seats at the table that we are pitted against each other.

I don’t want to compete with another woman for this seat. If I can teach you something about the industry and how to get farther, or at least skip ten steps that I had to struggle with, that’s what it’s about for me. It’s about making you feel safe while learning something new.

When I delivered a DJing workshop at Haven for Artists in Beirut, many women told me that a lot of the DJing studios in Beirut were not accepting women or were pushing them out. I had one application from a girl who was applying for her mother to take part. They said their mum’s dream was always to become a DJ and none of the DJing schools in Lebanon would let her in because she’s in her 50s, and they think that she’s too old. I let her in, straight away, and she was so happy. Honestly, my heart was so full after seeing her take part in the workshop.

If we’re not in these spaces, if we’re not making these decisions, then we’re not opening doors. And, we also need to think about how we can open more doors for Afro-Arabs, indigenous people from the region, and North Africans, because so much of our music industry is dominated by people in the Levant.

You’ve also been vocal about the genocide unfolding in Palestine. What responses have you received in the UK and in Europe?

I’ve been very political from the start of my career as a designer and as a DJ. Music is political, whether you like it or not. It is built on the backs of black, brown, indigenous people, usually in forms of resistance, and we have a responsibility to speak about these things. To expect an artist to simply be someone who has no values, integrity, or intelligence, who has no experience of these things, is illogical. For me, my existence, as a human being, is political, period.

Photography by Malak Kabbani, Photo treatment by Hussein Salem

You say more about some of the shifts you’ve noticed, both in the West and the region, since October 2023?

[In Europe], we’re seeing fears about safety, and we’re talking to clubs about extra security, which we’ve never seen before. I’ve noticed a shift in people’s energy. There’s a shared sentiment of exhaustion and need for collective solidarity, even if that is through the form of dance or listening to music as a means of expression. To be in a room where our language proudly plays out and knowing the majority around you share the same grief is bittersweet.

It’s been different performing in Europe vs. our region. If I compare performing in Beirut in 2023 and 2024, the heartbreak and lack of energy is so evident, it’s painful. I walked away from my show in June 2024 feeling even heavier – I had postponed performing in Beirut for so long because I couldn’t reconcile performing whilst my family in the South were listening to sounds of bombs around them, that were so close it was shaking their house. I would often check in with my family in the South to share my concerns with them, and they’d always say, “This is your work, and we have to carry on.”

You joined a Global Strike to call for a ceasefire in Gaza for a couple of months. What made you decide to start playing again, and to bring your politics into performance spaces?

One of the main reasons to go back was that I already had bookings way in advance, and rather than cancel, we thought it would be better to go ahead and use the event to raise funds for local activists. That’s what I did in Milan, and what I’ll do in Berlin and then Amsterdam. If it was really truly up to me, I don’t think I would have gone back, so soon. I think it’s to do with my Muslim upbringing. “Our people” are not used to being in this kind of club culture, right? So our experience of it is not as a form of resistance, it’s a 7afle (tr. party).

I was also grieving so heavily and mourning our people, it’s incomprehensible what’s happening, and it still is. There are phases of grief. Now, I’m in the phase of rage – I want to be loud, and I want to exist, and sometimes I want to stay home and retreat. When I went back and played in Milan, I had actually prepared a really dark energy set, but I felt that the room needed joy – not as in let’s forget, but like a Fuck You! kind of joy. I’m always searching for reasons to continue performing, but as soon as I’m on stage, I’m reminded of its necessity by our audience, our community – for many people, my shows are an opportunity to feel held or heard. We will not allow the Zionist regime to destroy our faith, our community.

Now, I start my shows by speaking on the mic and setting the tone in the space. I remind the crowd that I do not hold these events as an opportunity to forget, but for us to reset, come together, and fight harder against the Occupation and for the liberation of Palestine, Lebanon, Sudan, and beyond. I know the approach isn’t perfect, but none are. We are all learning and doing our best. My team and I have been worked hard in ensuring that all funding and venues are non-Zionist organizations. I’ve done this for years, but we’ve seen some organizations and institutions that we otherwise thought were strong allies take “neutral” stances or even attempt to censor our work – I will no longer work with them. It’s our responsibility as artists to do our due diligence when it comes to where we perform and which lineups we are a part of to ensure our values are aligned.

It’s hard to think of the future while we’re witnessing all this destruction. But, would you like to share any final thoughts about your future plans?

I definitely want to go into live [performance]. I really envisage myself going into this as a performer and artist, rather than simply a DJ. I’m already producing my own music, but I mean releasing more original music. I’m also collaborating with a lot of producers who I really respect, and some of those are coming out next year. There are a few vocalists like Nai Barghouti and Walaa Sbait who I’d like to work with. And there’s Bklava, a Lebanese-Irish singer and music producer here in the UK, and many other producers. I’m hoping that I can present some of it and that my following will just give grace to the fact that our tastes constantly change, and that they’ll come along for the ride. I don’t even know what that ride is, I’m just on it.

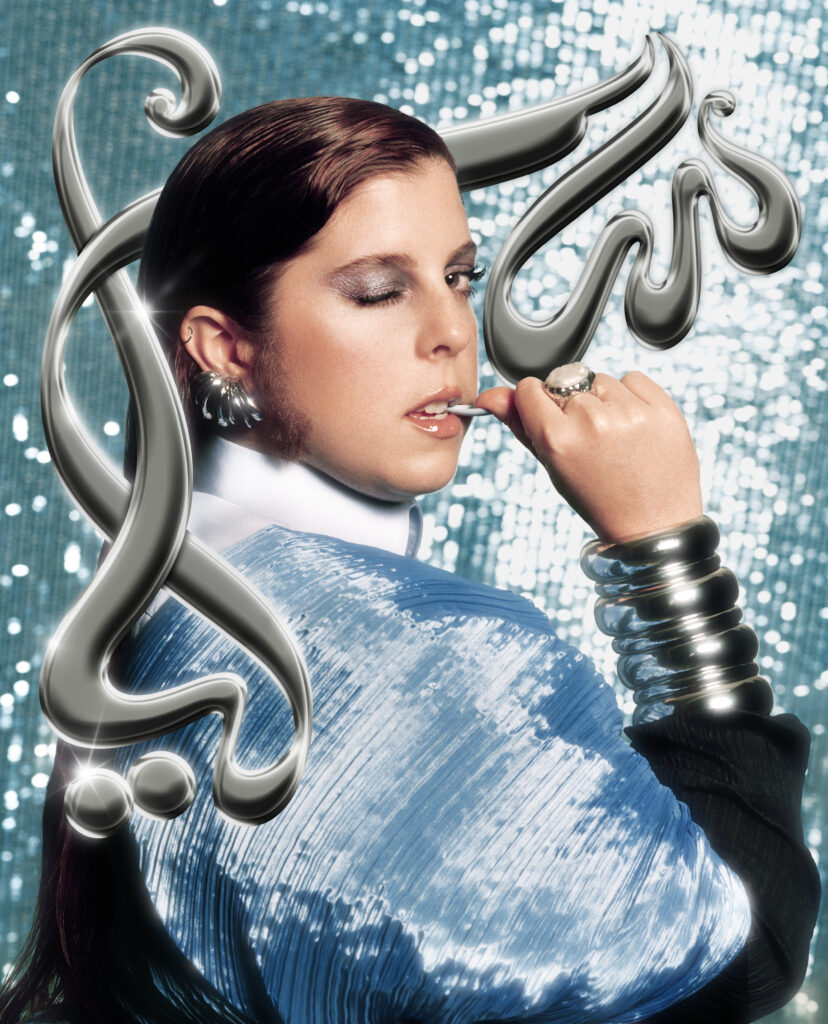

On The Cover

On the cover: Saliah

Photography by Malak Kabbani

Creative direction by Youssef El Sayed

Styling by Zahra Asmail

Makeup by Chiharu Wakabayashi

Hair by Masayoshi Fujita

Photo treatment & typography by Hussein Salem

Photo assistance by Taha Izzi

Cover design by Morcos Key

Cover design assembled by Alaa Sadi

Editor-in-Chief Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue