Written by Anwar Bougroug

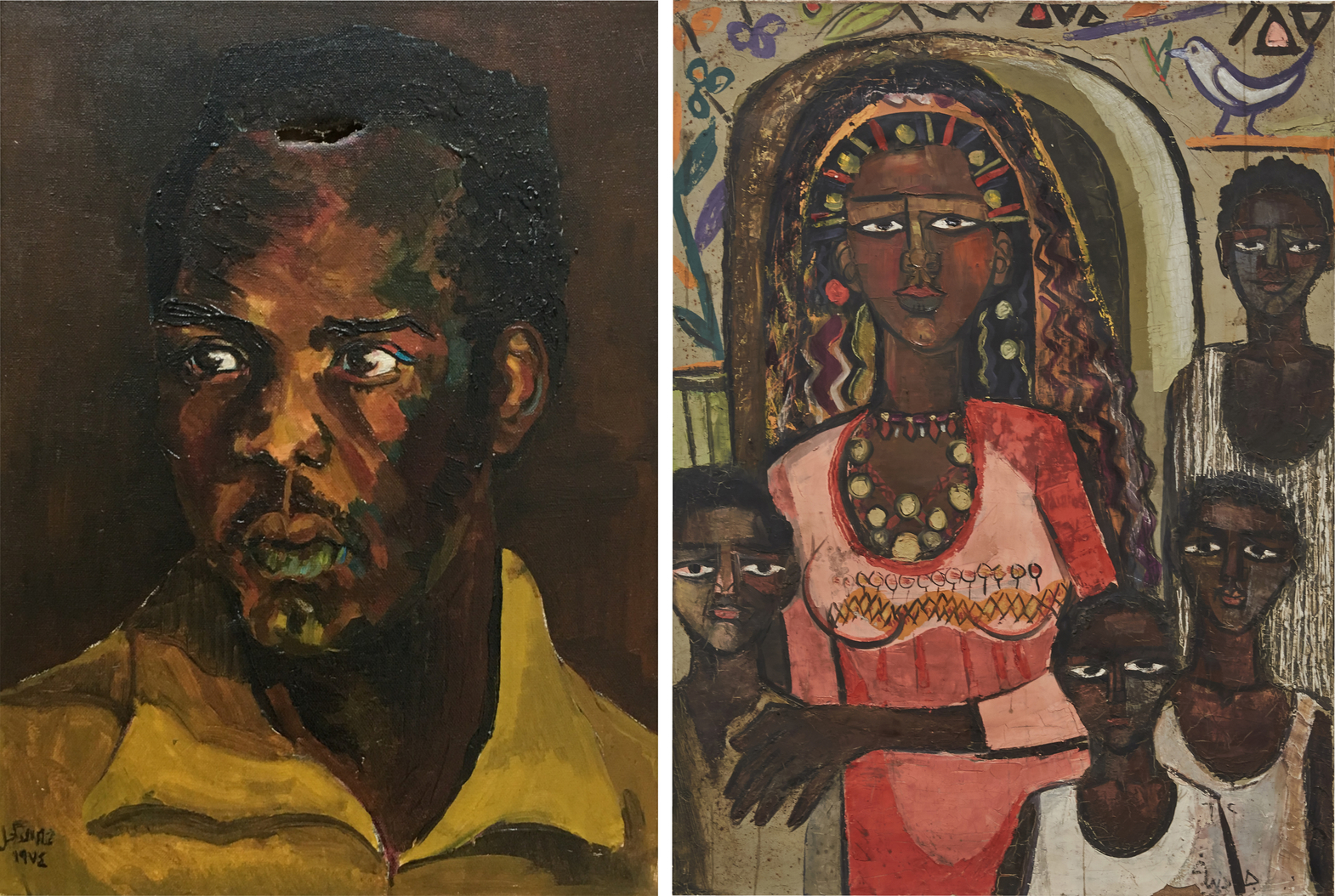

Featured Artwork: Sliman, 1974 by Tammam Al-Akhal (Palestine, b. 1935). Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

We are at a juncture in which the world is demanding justice for oppressed and marginalized communities: the end of anti-Black racism in the West, and a sexual revolution is beginning in the Arab world. On May 25th, four Minneapolis police officers killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man after an employee at Cup Foods, an Arab-owned store, called the authorities on suspicion that the African-American customer was trying to pass off a counterfeit 20 dollar note. In the grief following Floyd’s murder, one might assume that members of the Arab LGBTQIA+ community and its allies would show solidarity and take a pro-Black stance, but this is unfortunately not the case.

I first want to take a moment of outrage and morning to recommit to the vital work we must do in our own communities to fight Anti-Black racism, both as the cultural and systematic devaluation and discrimination of Black life. Despite the gravity of anti-Black racism in the Arab world, the issue remains inadequately addressed, and most of us are probably too familiar with anti-Black slurs and attitudes within our communities. We must collectively work to eradicate anti-Blackness and racism from anywhere it persists within the community.

What can we do to raise awareness and fight anti-Blackness in the Arab world?

History and Present of Anti-Blackness in MENA

Racism in the Arab world covers an array of forms of intolerance against non-Arabs and Afro-Arabs. It’s our responsibility to learn how non-black Arabs historically profited from, contributed and promoted anti-Blackness. Denying racism in the MENA-region is ignoring history.

In North Africa, the Sahara serves as a natural buffer between the two races. But at the southern edges of the desert, where the populations come together, relations are often tense. A spokesperson from Moroccan LGBTQIA+ rights and feminist organisation Nassawiyat said, “As North African we have a huge history of slavery and a big problem towards black people coming from other countries and want to reach Europe but are stuck in Morocco because the EU give money to the Moroccan state to keep migrants in her soil.” Sub-Saharan immigrants also suffer daily from verbal attacks and other forms of discrimination. Many black non-Arab immigrants often end up house-less due to lack of priority of public aid for refugees arriving from the southern borders of the North-African nations.

Most of Iraq’s black population still lives in Basra where they were brought as slaves from Africa more than 1000 years ago. Yet, to this day, some tribal Sheiks still keep blacks as slaves. Basrawis are also not as welcome in Basra’s political, commercial or educational life.

In Libya, during the Libyan Civil War in 2011, black people were massacred for their skin colour according to an Amnesty International report, and till this day, Sub-Saharan Africans fleeing war and persecution are captured and sold as slaves to “white Arabs” when arriving at the Southern border of Libya. Muammar al-Gaddafi was criticized for being a ruthless dictator and ruling with an iron fist, but even he acknowledged and apologized to Africans for their enslavement and gruesome treatment during the Arab slave trade. “On behalf of the Arabs, I’ll like to condemn, apologize, and express deep sorrow for the conduct of some Arabs – especially the wealthy among them – towards their African brothers (…) We are ashamed, along with our African brothers, when we recall this. We are ashamed of those who behaved in this manner, and especially the wealthy Arabs, who viewed their African brothers as inferior slaves.”

Painting ‘Nubian Girl’ by the Armenian-Egyptian artist Ervand Demerdjian. Images courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah

When celebrities in the Arab region wanted to express solidarity they didn’t leave the standard racist practice of blackface1, a practice that has roots in both the US and MENA regions. The particular racial history and ideologies of each is reflected in their respective media cultures. Lebanese singer Tania Saleh on Monday posted a photoshopped image of herself with an afro hairstyle and darkened skin captioned, “I wish I was black, today more than ever… Sending my love and full support to the people who demand equality and justice for all races anywhere in the world.” Moroccan actress Mariam Hussein also posted a photoshopped picture of herself with darkened skin, but later said she would delete the post after it received criticism on social media. Lebanese singer Myriam Fares’s 2018 music video for song ‘Goumi’ got plenty of attention online, showing singer in a faux jungle setting, and in blackface.

These posts are not the first instances of Arab celebrities being criticized for doing blackface, but are recent and salient examples of the denial and lack of acknowledgement of the slave trade and the anti-Blackness in the region. Examples like these show that racism in Arab media has been normalized, as has the ridiculing and dehumanising black people, and make evident the exclusion of black actors in the entertainment industry. The use of blackface reflects paternalistic attitudes towards blacks in the Arab world, who are seen as soft targets to mock, while also being regarded as violent and hyper-sensitive when they protest against racism.

Anti-Black oppression in institutions and the everyday

Racism appears in the Arab world on both institutional and systemic levels, and in everyday practice. Institutional racism, also known as systemic racism, is a form of racism expressed in the practice of social and political institutions. It is reflected in disparities regarding wealth, income, criminal justice, employment, housing, health care, political power and education, among other factors.

One example of deep-rooted systematic racism in our region is the kafala, the controversial employment framework governing migrant domestic workers in the Gulf, Lebanon and Jordan, where domestic workers often are treated like slaves, sexually abused, oppressed and exploited, and even denied their basic human rights. The system has long been criticized by human rights organizations because it legally binds a worker to their employer and without their employer’s permission, a worker cannot leave the job, change jobs, or exit the country.

A second example is that in our communities, we often quite bluntly refer to black people as “aabid”, “hartani”, “iswid” and “aazi.” People overlook or try to explain away the fact that these terms are offensive and have their roots in slavery and colonial rule in Africa and are derogatory terms in Arabic meaning “slave”, “servant” and “second-degree citizen.”

Malab Alneel, the media coordinator at Shades of Ebony in Sudan said, “Growing up in the Gulf and being more visibly black than visibly queer I experienced way more racism than I did homophobia, but what’s frustrating about this particular gulf brand of racism, unlike how openly and comfortably homophobic the society can be, is that a lot of the time it’s not seen as racism by the person or group making that remark… They make anti-Black remarks and ‘jokes’ but they don’t see them as racist, just funny or at times even facts, and when trying to explain how this is racist they’re quick to squirm, deny it, and blurt out the ‘I have black friends’ statement of the Arab world. ‘Bilal was the first muezzin, and he was black.’”

Malab reflected that, “It is aggravating that we need to educate the people around us about how they are insulting us and being disrespectful but I’m afraid that’s where the fight against anti-Blackness in the Arab world is right now, people need to be educated on their biases and that their jokes are not jokes at all.”

A dark-skinned Cairo-based writer, Abdul, said, “As a black Arab, I don’t have problems with people using ‘asmar’ or ‘khal’ to refer to a black person. In my opinion, ‘Aabid’ is just as derogatory as the N-word. I know a few non-black Arabs don’t mean any offence by utilizing it, nevertheless, I prefer not to be reminded about the history of the slave trade and the non-stop discrimination we experience as black Arabs.”

We also need to recognize the flip side of this. The embeddedness of racial ideologies also means that some Arabs also benefit from racial privilege connected with having Caucasian features and appearing as white-skinned. Otherwise known as racial passing, “white-passing” is when a person of color belonging to a marginalized community “passes” to identify as white, allowing them to have access to a certain amount of white privilege. Though they may face other kinds of discrimination, white-passing Arabs benefit from this racial hierarchy by not being recognizable as “other.”

On the Left: Sliman, 1974 by Tammam Al-Akhal (Palestine, b. 1935). On the right: Portrait of a Nubian Family, 1962, by Gazbia Sirry (Egypt, b. 1925). Both Images courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

Interlocking systems of oppression

What many members of the Arab LGBTQIA+ community perhaps aren’t aware off is the fact that modern queer liberation took place after the Stonewall riots, a series of rebellious violent demonstrations of the LGBTQIA+ community in New York City on the 28th of June, 1969. Thanks to a Black trans woman, activist and pioneer Marsha P. Johnson, who played a central role in the queer movement, we can today have pro-LGBTQIA+ debates in the Arab world as a result of the liberation in the USA.

Johnson’s legacy was reinvigorated on social media 30 years later after her death and a monument dedicated to her will be unveiled in New York in 2021 as a symbol of queer liberation all over the globe. It’s time we acknowledge that the queer movement in the MENA-region as we see it today owes a lot to a Black trans woman.

“For a person to maintain an anti-LGBTQAI+ stance while claiming to be pro-Black, they need to be ignorant of the movement they claim to champion. The Civil Rights Movement and all the movements that have pushed for the advancement and rights of the Black community have been too intertwined with the movements that pushed for the same for the LGBTQAI+ movements,” said Vincent Desmond, editor at Nigerian queer publication A Nasty Boy. He continued that, “The leaders of these movements have far too often been both black and LGBTQ for someone to come now and attempt to support one while pushing for the oppression of the other.”

Despite the intersectional discrimination on the basis of race, sexuality, and gender, anti-Black discrimination is still a predominantly reality for the queer Black community in the Arab LGBTQIA community. “People openly write they don’t want to meet any black people on their profiles on dating apps. It’s hard to navigate in the dating scene with Arabs, as people either see you as this extremely sexualized creature or as a dangerous criminal, which makes it nearly impossible to meet a non-nlack as a black person in Morocco,” said Ibrahim, a queer male based in Casablanca.

Finding a path toward collective liberation

“As an intersectional feminist and queer organisation we are against racism and we can’t fight for queer liberation if we don’t fight against racism,” says Nassawiyat.

Today, you can’t be anti-Black and pro-queer, and you can’t be homophobic and transphobic and pro-Black. Racial, ethnic, sexual and gender prejudices and discrimination are societal issues all intersect, and by understanding this and reflecting on why humans are discriminatory in the first place, I think we are able to understand the struggle. As Arabs, we face racism and hatred as we’re often linked to terrorism and Islamic extremism. As queer and non-gender conformists, we face oppression for not following gender norms. We should be able to understand the damage and violence caused by anti-Blackness.

The real pandemic the world is suffering from at the moment is white supremacy.

I hope that people can identify, whether it is from their own experiences of discrimination or not, how these systems of oppression overlap and empathize with those who face similar kinds of discrimination for different reasons. Rather than following the lead of Sofia Talouni, who used her position as a trans woman to encourage hatred against cis-gender, queer men, we must pull strength from these similarities to understand and find solidarity with the grief that Black communities around the world face.

“These experiences – being queer, being black, being marginalized – are far too often similar and far too often intersect with each other that attempts to extrapolate one to advocate for are pointless. If you are pro-Black, you must pro-everyone black, not just cis-hetero black people. If you are pro-LGBT, you must be pro-everyone LGBTQ. Our histories, our experiences play into each other too much for otherwise,” commented Vincent from A Nasty Boy.

I’m a strong believer in intersectionality, allyship, and building bridges between discriminated minorities. We have to recognize that change will only come when our allies and supporters rally together for our collective liberation. Collective liberation and intersectionality requires not just policy and legal change but the shifting of attitudes in our society, understanding history and claiming the value of Black lives. To shift the culture, we must do intra-community work, where we together liberate one another. We have to educate ourselves and our communities on what racism is and how we can tackle it, and you have racial privilege, or any other kind of privilege, make sure you understand that you’re lucky, and try to use that in order to be loudly anti-racism within your community.

Anti-Blackness is a widespread problem in the MENA-region and not exclusive to the US. We must have crucial conversations together with our friends and families about the things we can do to ensure we actively do anti-racism work. It is our responsibility to confront our households, neighbourhood, and places of worship when they perpetuate anti-Blackness.

As explained by American activist and author Angela Davis, “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anti-racist.”

Until Black people are liberated, until they are free from injustices and oppression, we will never be liberated. I hope we take this time to educate our communities to be more tolerant, open-minded and inclusive.

Black Lives Matter.