In conversation with Rheim Alkadhi

Photography by Natalie Halaseh

Make-up and styling by Samara Qamar

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Raed Ibrahim has long existed a few steps ahead, in humor, in expression, and in his navigation of the shifting social and political terrains that have shaped his life. His presence, whether in Amman, Beirut, or elsewhere, has always carried the ability to disrupt the familiar: a sharp, charismatic wit and a way of unsettling the assumptions of behavior and identity in the region. His artistic practice channels this instinct, transforming personal history and absurd political circumstance into intimate, incisive visual language.

This feature marks a renewed chapter in a conversation that began over a decade ago, when Raed and artist Rheim Alkadhi first met in Amman during a formative cultural moment of the early 2010s. Rheim, whose practice deeply engages with displacement, identity, and the urgencies of our present, found in Raed a counterpart equally attuned to the politics shaping their daily realities. Their friendship emerged through long walks, improvised “flower tea,” and shared efforts to decode the cultural and geopolitical absurdities surrounding them, a quiet method of survival in a region in constant flux. Though their paths later diverged across different geographies, they remained connected by a mutual insistence on imagining life beyond borders and inherited despair.

When we resumed this dialogue in late 2024, the stakes could not have been more urgent. As genocide continues in Palestine, and as Dahye (Beirut) was under ongoing bombardment, where his mother lives, the question of what it means to speak, create, and insist on presence became central once more. The conversation that follows is shaped by this reality: intimate, reflective, and grounded in a commitment to a liberated future.

Through Rheim’s thoughtful engagement and Raed’s ever-evolving practice, this exchange becomes a window into a friendship rooted in resistance, tenderness, and a persistent search for transformation, always a few steps ahead. It is a conversation that sits at the heart of My Kali’s Sana Wara Sana issue: looking back to move forward, and insisting on possibility even in impossible times.

You moved around a lot throughout your life: you were born Palestinian in Saudi Arabia, moved to Beirut in the midst of the Civil War and studied fine art at the Lebanese University, and have lived in Jordan since 2006, but continue traveling regionally and abroad for trainings, residencies, exhibitions and the like. What significance do these stopping points have for you, whether they are temporary or feel like home?

Growing up in Saudi Arabia, moving homes was very common; memories change as places change. Later, I wished I had a childhood neighborhood or house. In Lebanon, we had a family home that was normal, except for the war. When I started to leave for travel or work, I had other temporary houses.

When I came to Jordan, I thought I could build a home here. I have this idea of having a place that is forever, even though I always rent apartments. I first came as an adult, visiting for a family occasion, and came again later for my undergraduate research – there was no internet yet. A few years later, I did a residency at Darat Al Funun. I left Amman to do an MFA in Switzerland – I wanted to teach at university, and it was a good opportunity to read more and discuss – and started teaching when I returned.

Alongside your own work, you also teach art at the university level and mentor and curate exhibitions of younger artists. Have you always wanted to teach?

I don’t remember at what point in my life I developed that desire or longing for teaching, maybe through some of my professors, but I see it as an extension of my practices and vice versa. Working with students gives me the opportunity to talk about ideas and discuss related or unrelated topics, most of which go back to the point of how to express yourself and see reality. Fresh-minded people are amazing… sometimes (laughs). There is a useful idea or discussion, even when it comes to simple techniques or solutions to a detailed problem. We as artists need to be immersed in the learning and development process.

“Even when I lose optimism, I hold on to the belief that things can’t stay the way they are. Liberation isn’t an idea, it’s the daily, invisible work of survival.”

Photography by Natalie Halaseh. Make-up and styling by Samara Qamar.

You’re also delving into the archives of regional artists from past generations. As you gather and organize documents and ephemera, do any new or key points emerge regarding the history of art in the region?

Working in the archives is a good way to take a break from my work and look at things from a different perspective. It’s a great chance to reconsider the recent history, events, and ideas through the worlds of this or that artist. It could be through the articles they collected, or sometimes a clear written statement or artwork that comments or directly reacts to a certain event. Most of the artists whose archives I work on were born in the age of the [Palestinian] Conflict; they’re exactly the age of the [recent] history of the region.

We often have to separate and make decisions about what to archive and what to leave out, what’s public and what’s personal. The process of archiving individual artists, making them available to scholars, and seeing the outcomes of that scholarship is long. Only certain artists agree, and we only have what they kept, they represent themselves through what they save. One artist kept a full catalogue of images and magazine clippings, and captioned each with the date and everything. He was documenting his legacy and history. These archives tell the stories of their lives, but is not everything. It could be deceiving if an archive is taken individually.

While researching histories of art in Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, it always seems to start at the same point: somebody went to Italy or France or Britain and came back as an artist and/or art educator. Those are our “pioneers.” Many were also very rooted in and believed in producing something that looks like their culture. There is something in between, though. For example, when I was working on the archive of May Muzaffar, I came across a study she did, called “100 Years of Arabian Art.” In it, she mentioned how colonialism shaped the definition of art, reinforcing the idea that “real art” began with it, while all the artistic traditions, crafts, and artisans that existed before the white man were primitive or inferior. We believed that for a long time, and some still do, until the very same colonial man decided that it’s all art, and we repeated, yes, it’s all art. Like the borders that Europeans drew in their over 150 years of occupying and colonizing the region, not just Palestine, we act as if the line between what is art versus craft according to Western criteria is a given or established. We need to take initiative to find our own ways.

Has working with the archives of other artists changed how you organize your own records of making work?

Technically, it changed my ways of organizing, filing, saving, photographing or digitizing my work. It’s affecting the order of my archive or items, and I believe slowly I’m becoming more conscious about what to keep and sometimes what to delete. Hopefully, I’ll manage to find my method and way before it’s too late, and someone else will come and decide for me.

I know you are hesitant to assign years to your work. Why is this?

I don’t feel comfortable when I date my work, even on my website, because I think about it for years before actually doing it most of the time. Even when I finish my work, I often keep changing it. Each work is one idea that develops through time, and where it reaches is not necessarily where it began. It’s only now that I’m working with archives that I see dates as a very essential element, because it’s difficult to see an artwork or document without context.

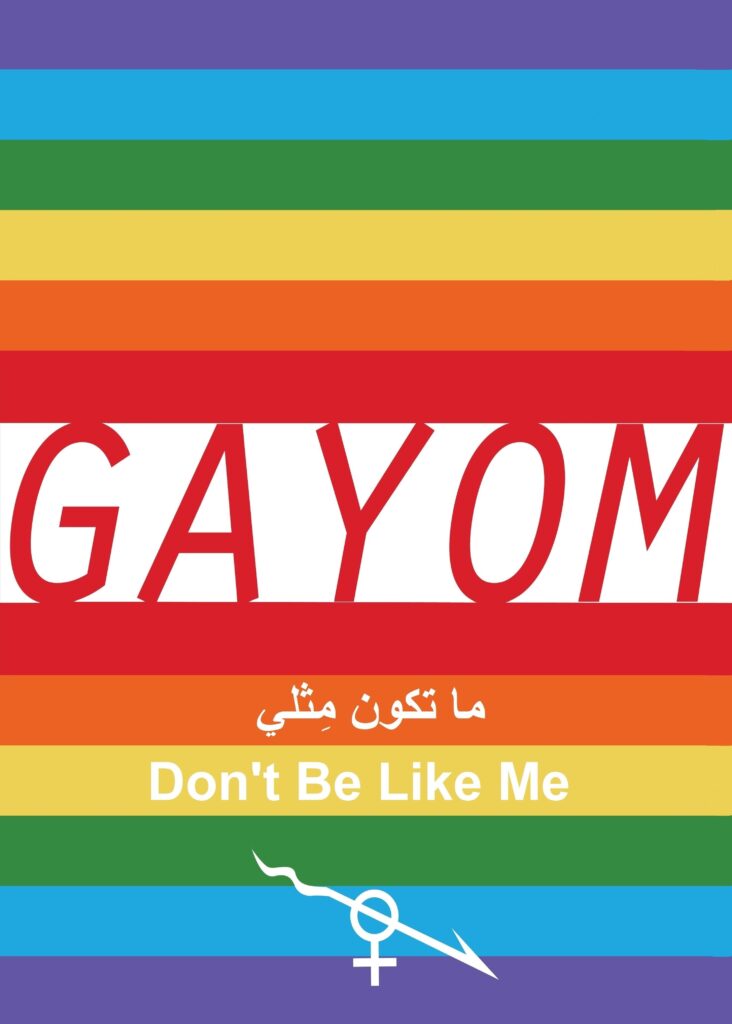

GAYOM poster, print on paper, 2009. HABIBI – The Revolutions of Love, IMA, Paris (2022–2023). Photo ©Alice Sidoli

Let’s turn to For Every Ailment, There Is a Remedy (2008). As a grouping, the objects speak like parables to the viewer, with a specific pharmaceutical-industry or market aesthetic. How does it fit in the timeline of your artmaking and thinking? Does it mark a shift in your method?

This work is significant for me because it marked a shift between painting to more conceptual work that uses different materials. It opened another horizon to my work, and from then on, I was more liberated in terms of materials and interpretation of ideas. I could be more direct and maybe literal, which I felt was needed in those times and circumstances. Now, I’m reconsidering that approach and longing to paint and draw, they are very fine mediums to communicate and reflect.

For Every Ailment, There Is a Remedy has many elements: design, writing, visuals, objects, leaflets, that allowed me to say what I wanted to say about political or social issues without necessarily being held responsible. With each social or political ill, from discrimination and homosexuality to normalization with Israel, there are these medications that solve the “disorder.” Like the writer of a storyline whose character has a controversial opinion, it’s the character, not the writer, who bore the weight of the message. The medication gave me distance to claim neutrality as an artist, allowing me to provoke without pushing the authority’s limits too far. At the same time, I was still able to guide the narratives in an indirect way and share this application with the participants, as if they knew that we are participating in this game.

Series For Every Ailment There Is a Remedy, 2009. Paper, plastic, glass, and stickers. Solo exhibition at Makan Art Space, Amman.

How does censorship or self-censorship factor into your work?

Self-censorship is part of growing up in the region. Both in Saudi Arabia and after I moved to Lebanon, talking about forbidden things was not accepted. Now, it’s different. I have this desire to work on projects that I believe have to be done, even if they are not showable. There are amazing examples of artists spending their whole lives doing what they want without showing anything, like that American outsider-artist Henry Darger, or even destroying it afterward. I’m fascinated by this idea. At the same time, I want to show my work, but am not sure if the public is ready to accept this type of work or me doing it.

Your work is multidirectional, but there are continuities in your approach. For example, The State of Ishmael (2009, ongoing) is a suite of objects and ephemera from the “occupation” of a town in Switzerland. It includes accessories for establishing a state: flags, citizenship, maps, coins — artifacts considered to “prove a prehistoric right” to a place. It follows the grouping-format of For Every Ailment, in some ways, but was geared toward an audience in the Swiss context. The work is a clear reference to Zionism, but how was it perceived in Switzerland?

It was in Aarau, a very beautiful town in Switzerland. There, I used various elements as you mentioned, which establish a nation even if it were invented or fake. But I feel that, as I explain my intentions, I’m also adding a layer to the work that was not there in the first place. If, for example, I say it’s a reenactment of what happened in Palestine, what does that add? I wish that there is something in the work itself that would convey the perspective. I want the work to be so direct that it doesn’t carry these double interpretations, because the situation we live in is so intense and so close, that you can’t be metaphorical or poetic about it. To answer your question, it was perceived well, and people were nice and polite. For me, it was done from the moment I installed it and maybe after a few photos. I wasn’t that interested in the reactions, or maybe that is just what I think now. Anyway, it was great to start it there, and I continued to develop the project over time and take it to different places.

The State of Ishmael, 2009–2010. Mixed media installation in public space, Switzerland–Jordan.

Your work Towers (2020) dives into a deep consequential abyss. It is literal and yet far beyond reach. All your references are open, and with them, you propose a deconstruction of politics, religion, materiality. There’s a harshness or garishness, like black smoke in the lungs; a viewer might find it difficult to submit, but it looms and enters the subconscious. It’s what I find surprising: the possibility to gain understanding of your artistic intention, of the world, through your work over time. It’s very rewarding. At this moment, five years on, how do you feel about Towers?

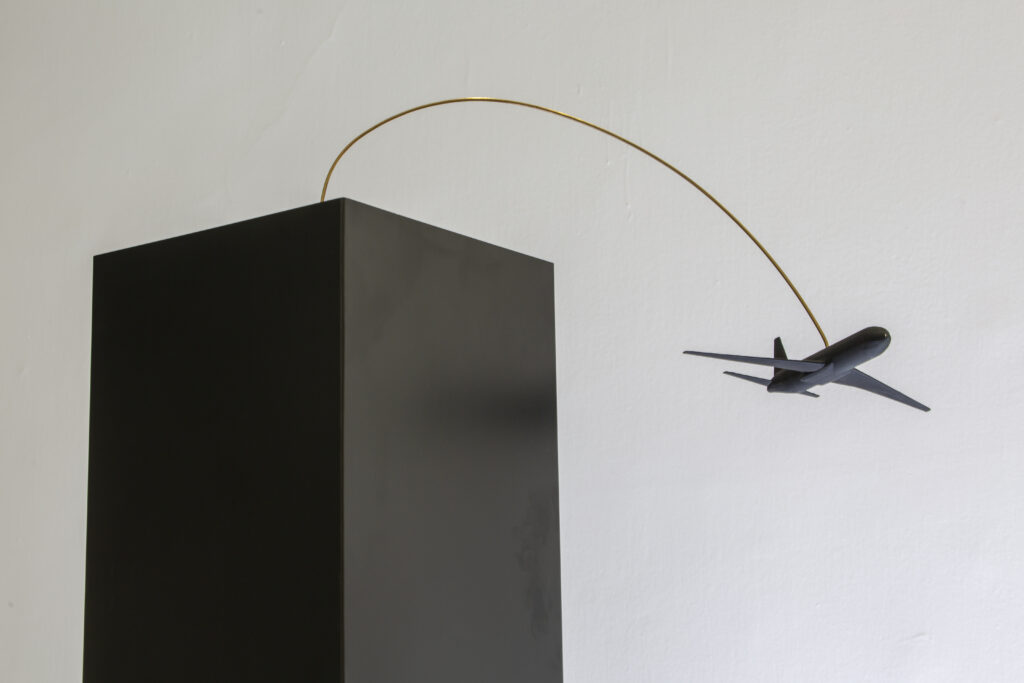

This work has been with me since 2001. I was in Amman at the time, and the collection of buildings and structures tried to take form many times in different ways. I had sketches and smaller-scale structures, doing a few towers throughout the years in different settings. I tried not to have too much input; they are almost the same proportions as the World Trade Center towers – even the proportions of the plane going into it. I just added the golden stripe of the Kaaba to one, so it’s clear where it came from. In some ways, I feel it’s too simple, almost monolithic. And with the cigarette, I wanted it to be so big that you feel small and almost want to bow down to this amazing American column with smoke on top.

Tower with airplane, 2021. Painted stainless steel, electrical motor, thermoplastic. Exhibited at Darat al Funun.

I’m so loyal to the imaginary image that I don’t understand what it means or why. I want to be honest with myself, and I have enough experience that I know I have to trust my feelings about something, even if I don’t understand why. Even if I don’t, I continue anyway and hope it brings out something meaningful or relevant. This gets back to what I was saying about shifting from painting to working with objects, how liberating it was to feel that I was coming closer to the things I imagined.

From left: Tower with golden stripe (painted stainless steel, electrical motor, gold leaf); Marlboro cigarettes (mixed media); Tower with airplane (painted stainless steel, electrical motor, thermoplastic); and Scaffolding (wood, jute string). Exhibited at Darat al Funun, 2021.

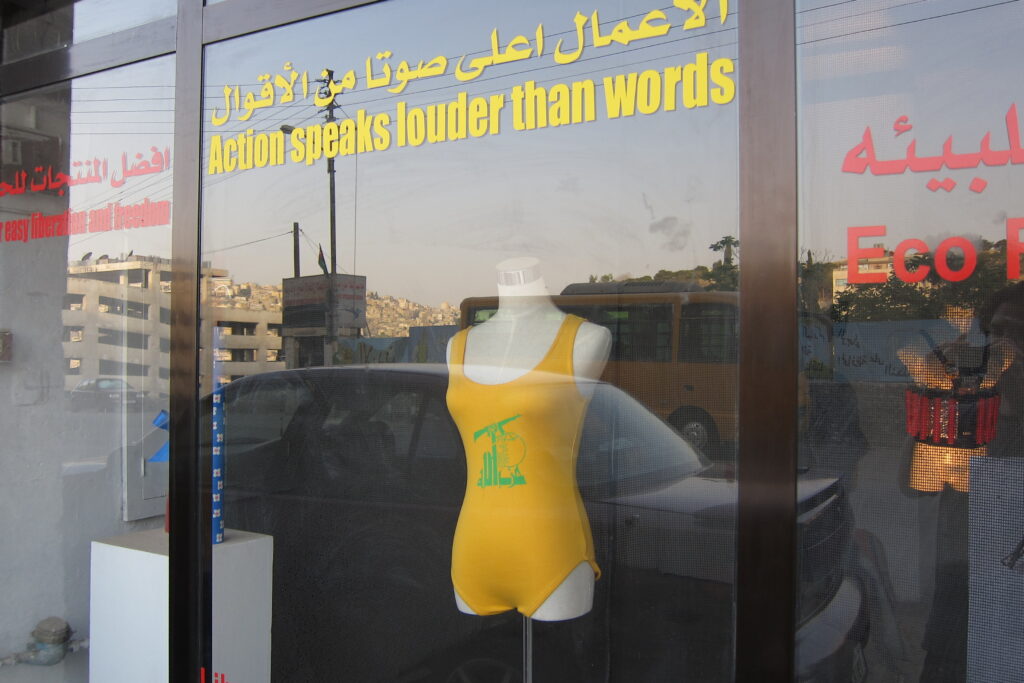

Can you talk about your project from 2012 with the yellow bathing suit?

In 2012, I created a ‘shop’ installation at a newly opened art space in Amman, ‘Why Not Sneeze’, which was formerly a car mechanic’s garage in Jabal Al Lweibdeh. It was after the revolutions of 2011 in the region, and the display had materials that were recognized as revolutionary; blank signs, Molotov bottles, spray paint, eggs, etc. One of the sculptures was a yellow swimsuit imprinted with the logo of Hezbollah, displayed on a mannequin.

The work emerged from a live speech that Sayyed Nasrallah gave after the war in 2006. Many supporters who were not from the ‘usual crowd’ came, including Christian people wearing the cross while carrying Hezbollah’s flag. It was striking. The majority Christian group Tayyar Al-Watani had come to an agreement with the Islamic party, showing it was a political issue rather than a religious one. The yellow bathing suit came about by combining this liberal thinking with a liberation movement.

The Dissent Boutique, 2012. A mixed media installation, exhibited at Why Not Sneeze, Amman.

I often think about how fearless and brave you are to push what might be, depending on where the work is seen, dangerous social buttons.

I might look brave when I do things like you described, or I like to be seen as a brave person, but I don’t feel brave. This is not in my nature. It’s very difficult for me to be in a war zone, or feel a physical threat. Doing art or being verbally brave, sometimes by mistake, or out of excitement, is not on the same level as people who put their bodies in public space to protest or go to war. I can’t pretend I’m doing my share in this tragedy through art; it will never parallel those who lose their lives or families, or get injured or lose their house/home, or even their neighborhood.

We live with shame and guilt constantly when others are killed and homes are being wiped out. The only really useful act is stopping the war. Art can be somewhere in the back, trying to support or help understanding or something like that. When everything is fine and there is peace, then my State of Ishmael can appear as an out-of-fashion project (laughs).

I’m contradicting myself all the time. I’m hearing the news while going out for coffee, then having an intense discussion about the situation in Palestine and Lebanon, going back to the studio to work, watching a movie at night, waking up to a new disaster, it’s not natural, or that 126 civilians killed in Gaza, while having my coffee. Then I do an interview about my work and my perspective about art and life.

IsraAid – from series For Every Ailment There Is a Remedy, 2009. Paper, plastic, glass, and stickers. Solo exhibition at Makan Art Space, Amman.

Within this challenging context, where many of us struggle to make useful contributions, what are you working on?

The “working” is there. What changed is the feelings while working, something related to the interpretation of what I produce. It seems like I’m doing the same type of work I always do, but in another state of mind, like it was always there but only now I can see it. We have been in a state of war almost all our life. But I don’t know what else to do. I feel it’s a luxury and doesn’t match action. It’s not fair. I’m still working, because it is my craft and I have the urge or the desire to make something. I work in my studio, there are always things to do, but I am not pretending it’s something else. What we do is imitate reality, somehow, or interpret and reproduce it.

I started a project in Singapore, where I do very simple paintings on colored paper, urban sites, and I draw on top of them once they dry. It’s the idea of drawing or painting a perfect city, but on top of it is another reality. In the process, I realized that it’s not about the city but how I see things, to complete the image, you have to tell your own narrative or perspective. At times, I layer different scenes, and by accident almost, it gave me a way to discover two ways of seeing and layering them together. It’s a way for me to engage and be occupied with an idea or visual.

My life has been this cityscape of urbanicide and destruction. The result of this destruction is very revealing, the edges and contrasts it brings out, in that it makes it possible to make the world that reflects feelings. If you concentrate on the image, for example a photograph or a video, the features condense into the feeling of that image. I then try to match these, to concentrate on the lines and shapes and colors to reenact or reproduce them.

Photography by Natalie Halaseh. Make-up and styling by Samara Qamar.

Your tools are not limited to the art/objects you create, but also the way you speak and present yourself and your political analysis, and how you propose new outcomes. As a final question, if we can’t effectively “work” at this time, what is the alternative?

Honestly, I think it’s hard to talk about “alternatives” when everything feels blocked or falling apart. But I also know that not being able to “work” in the usual way doesn’t mean we stop being artists or thinkers or people who care. When I can’t create or build or move forward with projects, I try to observe more, listen more, or just get through the day. Maybe that’s the alternative: to stay connected to what’s happening, and not to perform productivity just for the sake of it.

I don’t always feel optimistic. But I do believe that things can’t stay the way they are. Liberation isn’t just an idea, it’s something I think about practically, because it’s connected to survival, to justice, and to people being able to live without constant fear and loss. So even when I’m not making art, I’m still thinking, processing, and trying to stay grounded. That’s work too, maybe not visible, but real.

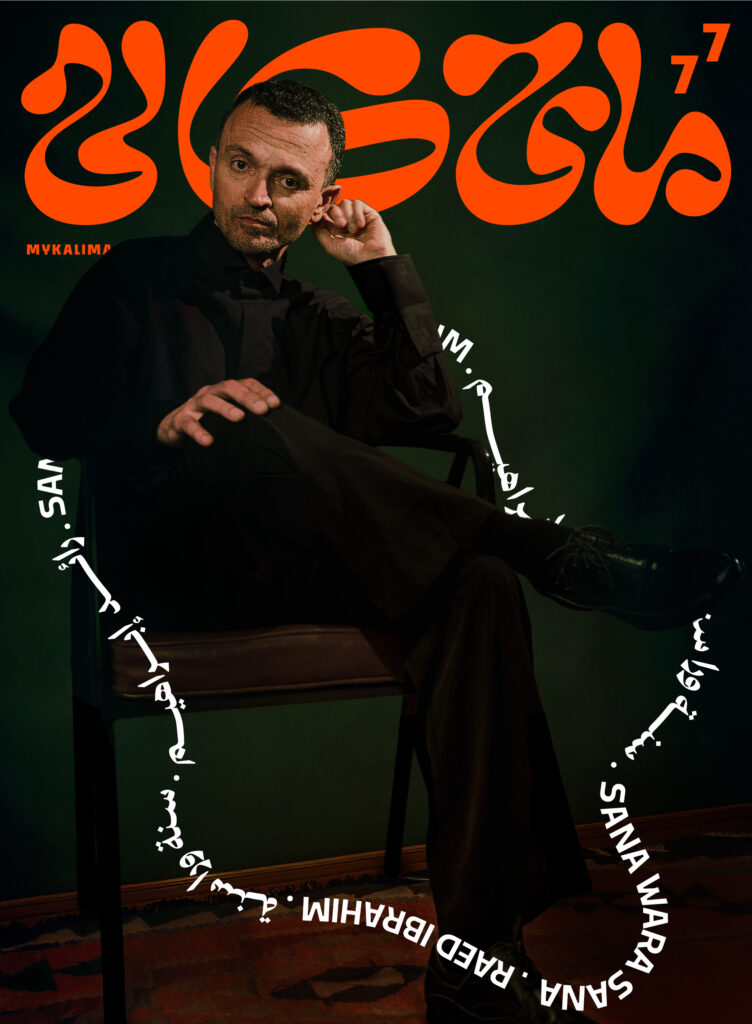

On the cover: Raed Ibrahim

In conversation with Rheim Alkadhi

Photography by Natalie Halaseh

Make-up and styling by Samara Qamar

Cover design by Morcos Key

Cover design assembled by Alaa Sadi

Editor in Chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue