In Conversation with Karim Kattan

Photography by Mohsen Othman

Styling by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Hair by May

Nails by Mathilde Guyot

Stylist assistance by Justine Schwaab

Editor-in-chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

In her documentary work, French-Palestinian-Algerian filmmaker Lina Soualem explores the complexities of her multi-layered identities and family histories. She creates polyphonic work from silenced or scattered memories. Inviting her relatives into the frame, she opens spaces where they can remember, speak, explore and enact their histories. Her films empower her grandfathers, grandmothers, aunts, her mother and father —and herself— to reclaim and reinterpret their personal narratives, which are deeply rooted in the traumatic legacies of colonized Algeria and Palestine. Though intensely political, Soualem’s work carries a poetic sadness, a gentle longing and wistfulness tempered by sharp humor, that transcends the immediacy of political struggle, revealing delicate portraits of yearning and the intricate labyrinths of dreams and desires.

Whether filming her Algerian grandparents in Their Algeria (2019) or her Palestinian mother, grandmother, and family in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023), Soualem weaves political and intimate voices into vibrant tapestries. Her cinema is collective and personal, vulnerable and resistant, energetic and meditative. The resulting images form colorful, striking vistas of inner and outer landscapes, capturing the lives of men and women navigating histories of power with strength and agility. In a time when the destruction of Palestinian life is on full display, her work feels like a quiet, stubborn response: a refusal to disappear or be summed up in a neatly framed category.

When we met to discuss her work in Paris, Lina spoke at length about the responsibility that comes with this work, the methods she used to create space within the frame for her family, and what the process of uncovering memories or making sense of scattered stories can mean for the filmmaker, her subjects, and the audience.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Coat; Ho Tin Albert Chan. Shoes; Acne Studios. Glasses; Dior.

Photography by Mohsen Othman.

Your work often explores the theme of transmission, as we see in Their Algeria and Bye Bye Tiberias, each in its own way. As a filmmaker, you engage with women in your family, trying to break the silence for various reasons and ensure that something meaningful is passed on. If you could pass something on to future generations or other communities, what would it be?

I think the answer is in your question. When I capture the memories of people in my intimate circle, my family, I know it’s not just for me. It’s not just about reactivating my own story, but also about connecting to a collective one. The intimate stories I capture contribute to collective memory, enriching the histories of Palestinians and Algerians that are often erased or forgotten. For Algeria, it’s colonial trauma; for Palestine, ongoing colonization and deliberate erasure.

Intimate and collective memory are intertwined for me. Through my films, I’m exploring this connection and what personal memories reveal about the collective story. Transmission is like a circle: by capturing memory, I aspire to preserve something to transmit, a proof of existence.

A film today is a digital object that can’t be erased, unlike physical film. I think this could be my legacy.

Top; ESTHE. Blazer; Valentino. Shoes; Acne Studios. Bracelet; Acne Studios.

Photography by Mohsen Othman.

Speaking of legacy, and turning to both films, you’ve recently completed Bye Bye Tiberias. To me, there are clear differences between Their Algeria and Bye Bye Tiberias. I’d love to hear from you—how do you relate to Their Algeria today?

Their Algeria will always be my favorite because it was my first, spontaneous act of capturing memory, filming, and telling a story—taking risks and exposing my vulnerabilities. I filmed people who had never shared their stories, unsure if they ever would. I had no idea they would eventually open up, or that their silence came from deep pain and uprooting. It taught me about exile, transmission, and so much more.

It connected me to my Algerian grandparents, especially my grandfather, who I had always felt distant from. In the end, I felt close to him, and it gave me hope that you can understand someone, even later in life. He was 85 when I started filming, and I only truly got to know him in his last three years. Without Their Algeria, I might have always seen him as a hard, strict man and never understood him.

Now, when people tell me they’d love to film their grandmother or have conversations like this, I always encourage them to try, even if it doesn’t work out. I was lucky my relatives shared their stories with me; some might not. It was essential for my understanding of myself and my place, even in France, where I was born.

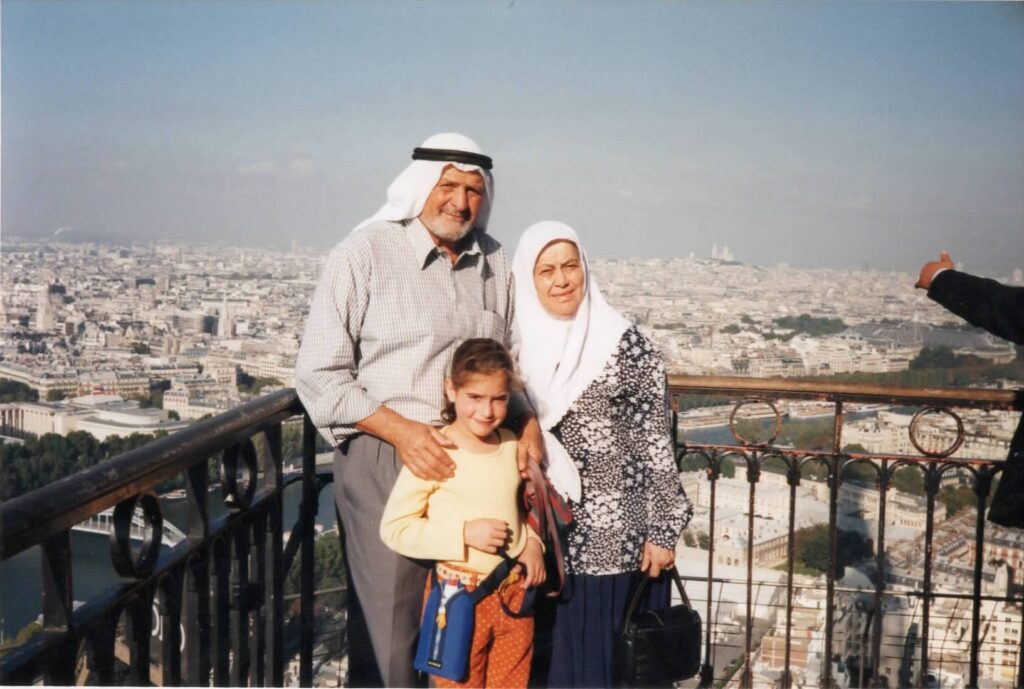

Paris – 1990’s – From left to right, Said Abbass, Lina Soualem, Neemat Tabari.

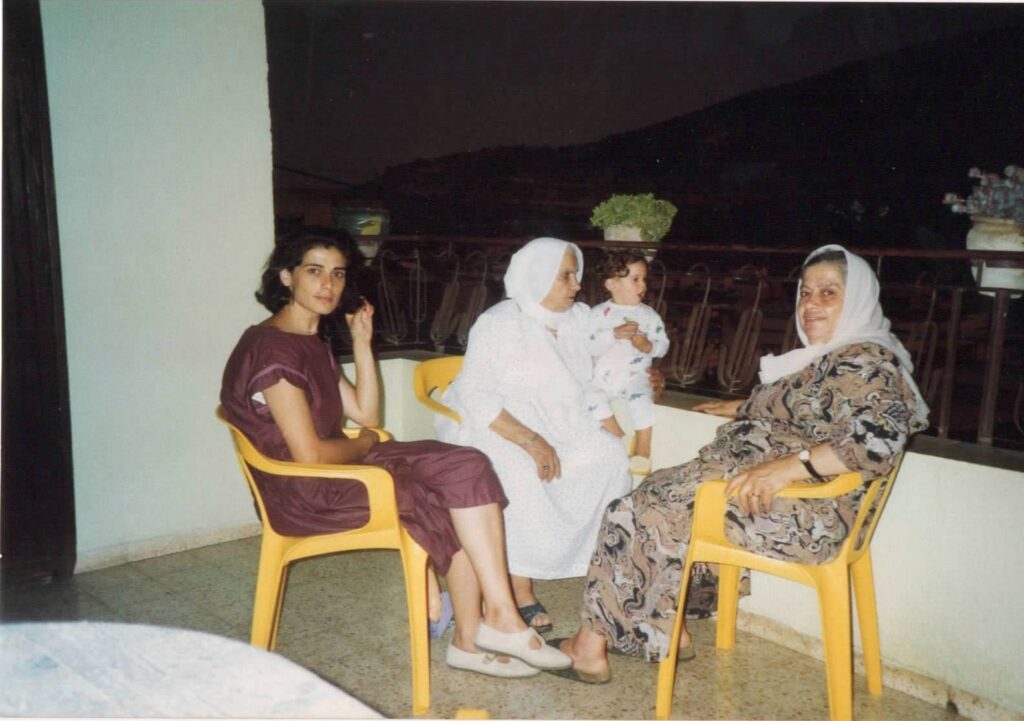

Deir hanna – Palestine – 1991 – From left to Right : Hiam Abbass, Um Ali Tabari, Lina Soualem, Neemat Tabari

On this note, how do you transition from Their Algeria to Bye Bye Tiberias? Both films, I think, share a preoccupation with silence. If I had to describe them, each finds ways to undo the silence surrounding traumatized bodies and minds and to reactivate memory—but they’re still very different films. I’m curious, how did that transition happen?

At first, it didn’t feel like a choice. I never planned to make a second film while working on Their Algeria, because I wasn’t even sure I could make one at all. I filmed not knowing if it would become a film, what it would look like, or how people would respond. It actually felt natural to start filming my grandmother in Palestine while working on Their Algeria, as if I couldn’t help but film her. I had become aware of the risk of losing family memories and stories if they weren’t passed on, especially as I saw my Algerian grandparents aging while filming them. I saw how easily these stories could disappear if I didn’t act.

When Their Algeria was released, many asked if I would make another film about my Palestinian family, and at first, I said no. It took me a while to finally commit to making the second film. For a long time, I kept saying, “I’m trying, but I don’t think it will work.” I was afraid of diving back into painful memories and of facing the women in my Palestinian family, especially my mother. It felt more challenging and frightening to expose another part of my identity—one that has always been denied and not recognized.

You mention the common theme of silence, but for me, there’s a difference. Their Algeria was about breaking silence, while Bye Bye Tiberias was about gathering scattered stories and creating a sense of continuity after exile. In Their Algeria, I didn’t know what lay behind the silence, but in Bye Bye Tiberias, I did.

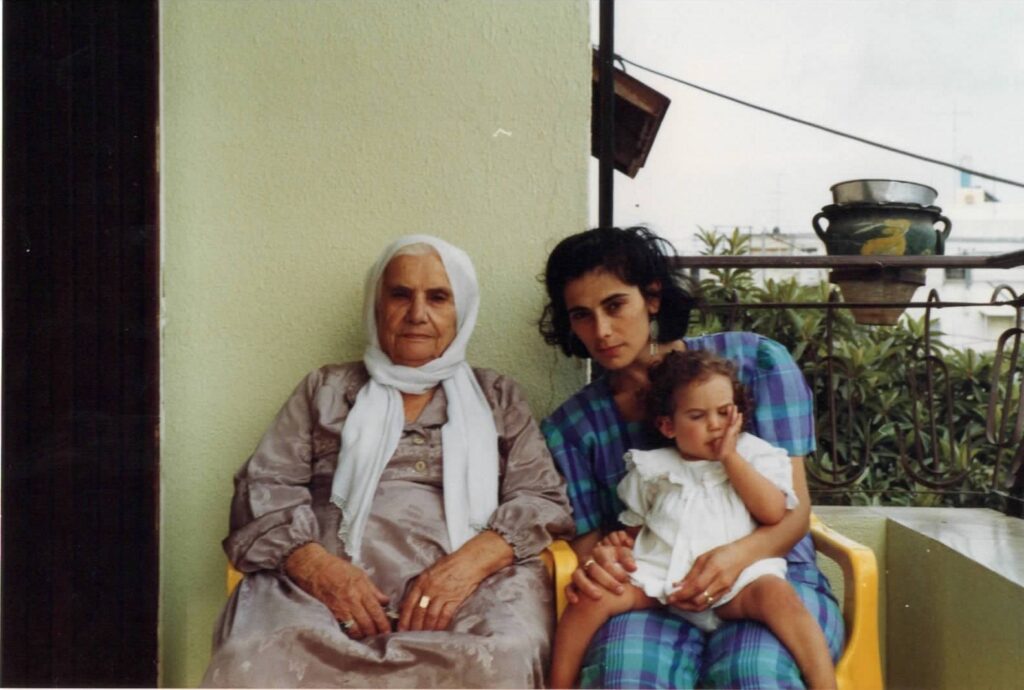

Deir Hanna – Palestine – From left to right, Um Ali Tabari, Hiam Abbass, Lina Soualem; 1991

Both your grandmother and your mother ask you a similar question while you’re filming them— something along the lines of, “Why are you doing this? What are you looking for?” They ask this of both their granddaughter/daughter, but also of the filmmaker facing them. I imagine it felt very different filming people who had never been on camera before, bringing them into the world of the image, compared to filming your mother, who is an actress.

It was much easier for me to film my Algerian grandparents. The camera was like an extension of my body; it became invisible to them. They weren’t worried about how they looked on screen because they weren’t as aware of it. But with my mother, it was much harder. She’s used to film sets, familiar with the camera, and very conscious of what she was saying, responding to me as if I were a journalist. She had to stop addressing me as a stranger, and I had to find the right way to address her, not just as the daughter trying to understand, but as a woman and director.

On the left: Coat; Ho Tin Albert Chan. Shoes; Acne Studios. Glasses; Dior.

On the right: Top; ESTHE. Blazer; Valentino. Shoes; Acne Studios. Bracelet; Acne Studios.

Photography by Mohsen Othman.

You also had some strategies that you used, right?

Because she’s an actress and more comfortable with acting, I used moments from her youth—stories she had told me or ones I knew from others—and asked her to re-enact them, to step into the shoes of her younger self at a specific time and place. There are two scenes, one in Haifa and one in Jerusalem, where I asked her to reenact moments from her twenties. To help her reconnect with that younger version of herself and feel what she felt back then, I needed her to be in the same places, with people who were there at the time. I also wrote for her, asked her to read my words back to me.

Why did you do this?

I originally planned to collect the stories through my grandmother’s account of the Nakba and what my mother would tell me. But my grandmother passed away during filming, and I realized my need wasn’t just to collect their stories—it was to tell them through my own lens. I wanted to share their stories and how I felt about them.

It wasn’t just about gathering their words and putting them on film. It was about reflecting on what they told me, imagining what I didn’t know, and the questions I could never ask. Having my mother read these texts was part of reactivating the transmission: she told me about the women in our family, and read my words about them. It felt like a transmission in a circle, where both of us were active in this process.

It’s a dialog and a polyphony: different voices weaving the stories together.

It embodies our stories, gives complexity to our shared experience, and allows our questions, contradictions, fears, and the reality of exile to exist at the same time. This is the consequence of our loss—so many gaps and fractures—and the need to tell our stories. If we hadn’t lost so much, I wouldn’t have needed to make this film this way. The form of the film is an answer, a reflection of the Palestinian story, which is scattered, unofficial, and unrecognized.

Bye Bye Tiberias is like an archipelago of disrupted and fragmented territory. The stories are deeply touching and often sad, but it’s also a very funny film. There’s so much playfulness, not only in the strategies you use but also in your conversations with your mom, and between your mom and her sisters. Both films have a humor to them. It feels like a reflection of you, too—your sense of humor really comes through.

Yeah, it comes from the people I film. In Their Algeria, with my grandfather, the humor is more cynical, while with my grandmother, it comes from shyness. She’s funny without trying to be. I think her humor stems from having to remain as innocent as the 17-year-old girl who was married and brought to France, surviving a life where she had no choices, lived under colonial rule, and was denied her identity and freedom.

In my Palestinian family, though, humor is more conscious, a mode of survival and communication. It comes from love and complicity, a way to keep going. I feel my aunts had more choices in life, so their humor is more empowering. This humor is common in many Palestinian families; it’s a way to cope with reality, but it comes from intelligence, not despair. It’s how they connect and keep the force of life alive. Even if it’s through cynicism or irony, humor is a form of resistance.

When I capture the memories of people in my intimate circle, my family, I know it’s not just for me. It’s not just about reactivating my own story, but also about connecting to a collective one. The intimate stories I capture contribute to collective memory, enriching the histories of Palestinians and Algerians that are often erased or forgotten. For Algeria, it’s colonial trauma; for Palestine, ongoing colonization and deliberate erasure.

Blazer; Acne Studios. Shirt; Sara Vukosavljevic. Tie; Dries Van Noten. Tights; Calzedonia. Shoes; Acne Studios.

Photography by Mohsen Othman.

It’s very irreverent… How was the documentary received by them? In our cultures, there’s a particular sensitivity around private lives and intimacies, so making films about one’s family is a bold gesture. First, could you share a bit about how your family reacted when they saw the film?

The scariest part for me was showing Their Algeria to my Algerian grandmother, especially since my grandfather passed away before seeing it. I was afraid she’d feel shy or uncomfortable. But after filming her for three years, I knew she trusted me. I was filming people I love, and I would never want to make them uncomfortable. Still, I was nervous. When my grandmother saw the film, she reacted exactly as in the scenes—laughing at the same moments, making the same comments. It was incredibly powerful to feel that I had captured her reality. Afterward, she was eager to share it with others. My Algerian relatives wrote to thank me for telling their story, which had never been told—the hardship of exile and the impact of French colonization in Algeria through the eyes of an immigrant family. They thanked me for bringing their memories to life and making them visible.

This gave me the confidence to do the same with Bye Bye Tiberias, being mindful of the limits I didn’t want to push. Filming my aunts in Palestine was tricky at times—they sometimes shared personal things they might not have wanted in the film. But their trust in me, allowing me to ask certain questions, made me feel supported, even before they saw it. When they finally saw it in Amman in July 2024, it was beyond my expectations. They were moved, proud, and even wanted to tour with the film. They attended screenings in Jerusalem, Haifa, and Nazareth, doing Q&As afterward.

Even my mother, who was initially reluctant about the film, has since expressed how proud she is. During the tour, she told audiences that she’s proud her family’s story is immortalized on film by her daughter. She even shared something she’d never told me before—that she had always dreamed of filming and telling the story of her grandmother and great-grandmother.

Did your Palestinian family see Their Algeria?

They did, during the festival Palestine Cinema Days in 2019. They were moved because they connected the story of French colonization of Algeria with the story of the Nakba. They connected the silence of my Algerian grandfather with the silence of my Palestinian grandfather.

And did your Algerian grandma see Bye Bye Tiberias?

She came to Paris especially to see it when it was released last year. She loved it.

On the left: Blazer; Acne Studios. Shirt; Sara Vukosavljevic. Tie; Dries Van Noten. Tights; Calzedonia. Shoes; Acne Studios.

On the right: Full look; Acne Studios.

Photography by Mohsen Othman.

You’re working on a feature fiction film now. What is it about? How does this process differ from your previous work with documentaries?

I’m excited to work on something new, though it’s still about the same themes that I explored in my previous films: finding your place in your family’s story, balancing personal aspirations with family duties. I want to tell the story of an Algerian family living in Spain. It’s important to shift the way we view Algerians, beyond the French colonial perspective or contemporary Algerian perspective. Moving to another country allows characters to be more complex, free from the usual stigmas. The stereotypes around Arabs, Algerians, Palestinians — I want to fight these stigmas.

Documentary can be a lonely process—Their Algeria was just me and my editor, Gladys Joujou. With Bye Bye Tiberias, I collaborated more, with Nadine Naous, Gladys Joujou, you, for the writing and Frida Marzouk for the image. In fiction, you need a bigger team. You need to exchange visions, make decisions together. That’s what I love about cinema — the collectiveness.

What would be the one thing that you think all the women in your family — your grandmother, your mother, your other grandmother, your aunts — have taught you?

They are a miracle. The way they’ve been able to pass down such incredible values and so much love to their children and grandchildren, despite being deprived of everything, feels truly miraculous. It’s a profound responsibility—and also a great privilege—to have received all of this from them.

On the cover: Lina Soualem

In Conversation with Karim Kattan

Photography by Mohsen Othman

Styling by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Hair by May

Nails by Mathilde Guyot

Stylist assistance by Justine Schwaab

Cover design by Morcos Key

Cover design assembled by Alaa Sadi

Editor-in-chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue