Words by Aya Ahmad

Photographs by Ali Asfour

This piece is a supplement within the “Frenquencies” issue

Street art – including graffiti and commissioned murals – is often framed as an important form of expression that gives a voice to the voiceless. From the streets of New York to the Apartheid Wall in Palestine, this art form has become a way for artists to communicate their thoughts and feelings with the public.

In Amman, Jordan, street art is a rather controversial subject. Street art became more common in the wake of the Arab Spring, when public walls across the entire region became canvases for political expression and resistance. Ammanis took to the streets with their paints and brushes, inspired by the revolutionary energy and bursting with ideas of freedom, anger, and justice, to weave images of resistance and resilience into their city’s cultural fabric.

Soon after, street art became increasingly institutionalized and incorporated into urban planning and beautification projects, aligning with the government’s mission of turning Jordan into a popular destination for cultural tourism. And while using street art to boost the country’s strained economic climate isn’t necessarily a negative thing, we must raise an important question: What role do these commissioned murals serve in our streets today?

Based on a series of interviews, surveys, and image analysis, this article asks: What is motivating street art in Amman today? How have NGO and state agendas changed this streetscape, and whose interests are represented in “public art”? And, how do street artists navigate censorship and inconsistent policing to take back the walls and reflect the people’s thoughts and needs?

“Public” Art: The politics of commissioned street art

Vibrant murals cover the Amman’s walls, and are concentrated particularly in areas with high visibility. At first glance, it seems that Jordan’s public space is a haven for artistic expression and freedom, but these images are part of a more complex story of urban transformation and competing agendas. We have to ask, who controls the narratives of the streets, and how public is public space, really?

Many Ammani street artists have turned away from making explicitly political art in recent years, focusing instead to collaborate on larger projects that will bring color to an otherwise monochromatic city and foster positive community. But as these projects grow in scale and garner the interest, funding, and support of foreign governments, NGOs, and municipal authorities as a tool of development — and as more artists seek to build careers out of street art — they become more entangled. While these commissions undoubtedly project important messages – for example, promoting cultural tourism or public health campaigns – they often reflect the funders’ interests and priorities rather than what matters most to the artists and people living between those walls.

Further complications emerge even in cases when murals are commissioned to produce commentary on issues that deeply connect to the cultural experience of local communities. In some cases, the funder’s lack of context may create further misunderstandings; and in others, they may curtail the expression of commissioned artists who have that context (whether it be in aesthetic or topic) based on their priorities or vision. In either case, artists are forced to navigate interests of funders and communities to complete their tasks. This growing pressure of external agendas raises critical concerns about who controls the narrative in Amman’s streets. As these commissioned works multiply, street art risks becoming less about self-expression or representativeness, and more about promoting institutional goals. Restrictions on the kinds of messages and styles permitted on these walls, as well as artist’s financial dependence on sponsors, leaves less and less space to address sensitive social issues, including questions of identity or resistance.

Images by Ali Asfour

Engaged Street Art: Ambiguous Policing and Censorship

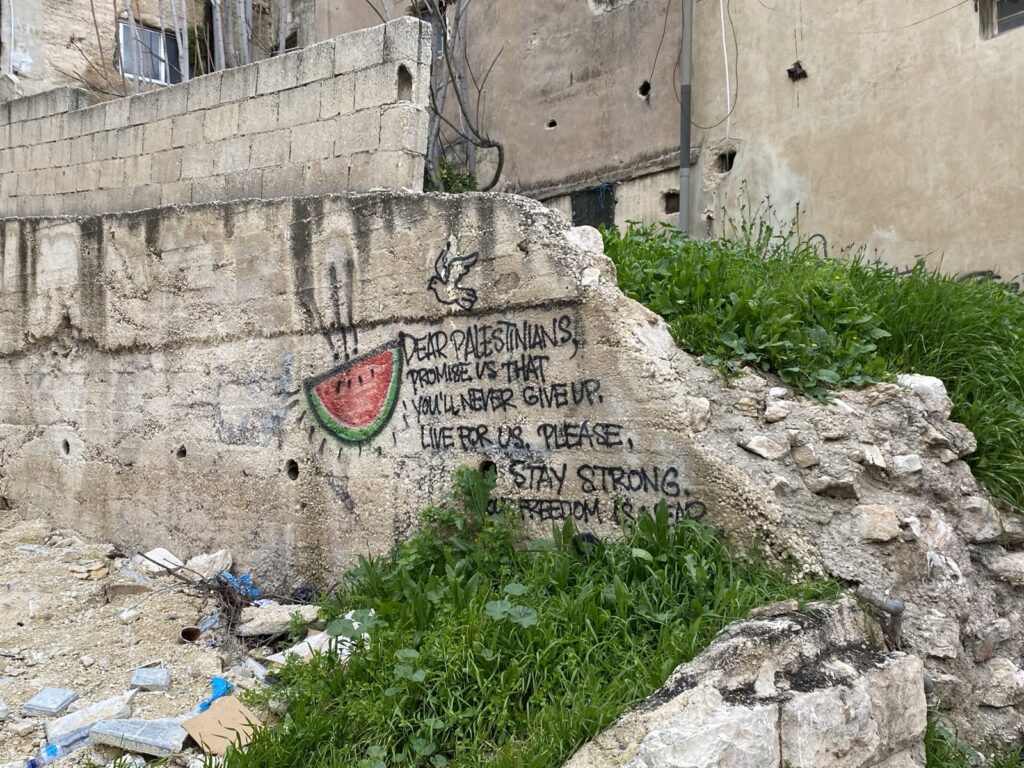

As researcher Kyle Craig discusses in his 2022 article, “The Challenges of Palestinian Solidarity in Amman’s Street Art Scene,” Jordan’s streets filled with passionate and angry citizens in Summer 2021 to protest Palestinians’ forced displacement from Jerusalem and the bombing of Gaza Strip. Young Jordanian street artists’ feelings of responsibility broke them free from the usual constraints and expressed their solidarity with Palestine by creating politically charged murals. Craig quoted a muralist in her mid-twenties, who remarked, “There’s energy around Palestine right now. It’s less scary to make art about these things when you’re not alone.”

However, once the protests cooled down, many street artists went back to non-political projects in fear of censorship and conflict with authorities. On one hand, the consequences of breaching the country’s “red lines” – including criticism of the government and its political allies, references to religion aside from abstract celebrations of coexistence, references to social justice issues, or expressions of non-Jordanian nationalism – could mean artists’ facing interrogation by authorities for years after their murals or graffiti were erased. On the other, there’s a lot of vagueness surrounding what those “red lines” even are.

In many instances, policing is inconsistent, leaving artists confused about where the line actually is. Some murals and graffiti about Palestine are left untouched by the police, while very similar ones get painted over. One street artist created a mural featuring a toddler being photographed for a mugshot, criticizing Israel’s child detention practices. While the nature of this mural isn’t dangerous or promoting violence, it was swiftly erased. Yet, in Jabal al-Weibdeh still stands an untouched mural of a masked figure holding the Palestinian flag and a Molotov cocktail, a direct symbol of Palestinian resistance.

Another layer of ambiguity comes when the public’s pushes for the erasure of street art, often in the name of public morality. Misinterpretations of murals and graffiti, even those that promote a neutral message of solidarity, may be reported to authorities and painted over. For example, authorities quickly painted over the mural commemorating Egyptian LGBTQ activist Sarah Hegazi featuring her face with the rainbow flag, and a quote from her final letter, “but I forgive.” Was it the rainbow image or her significance as an activist that triggered such a response?

When authorities attempt to cover murals, they often do so haphazardly, leaving parts of the mural peeking through the black or white paint. More than just a means of erasure, this black and white paint becomes a message in itself, the true “writing on the wall.” It symbolizes the country’s attempt to control public narratives and the limits of public expression and civic engagement, revealing more about the political climate of the country than the murals themselves.

Navigating this Streetscape

Navigating funding agendas, censorship, and inconsistent policing has not silenced artists, but pushed them to get creative to reclaim public space through indirect symbols and subtle language, staying under the radar of authorities and unwanted public attention. @wawi9_1‘s tribute mural to British-American rapper, MF Doom, is an excellent example of this, incorporating references to Palestinian rapper Muqata’a that were only legible to those attuned to the struggle.

Image by Ali Asfour

This reminds us that the street is a powerful domain for communication, resistance, and connecting people, and that resistance is alive despite being constrained.1 Thus, the contestations around controlling street art in Amman and the images on the walls – whether commissioned or popular works, murals or graffiti, celebrated or blotted out – points to a larger struggle for autonomy and civic space that represents the people.