Interview by Elias Jahshan

Photography by Mohsen Othman

Styling by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Stylist assistance by Marie Khx

Editor-in-chief: Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

Palestinian pop artist Bashar Murad made waves across social media in Spring 2024 for participating in Söngvakeppnin, the annual Icelandic contest to determine who will represent the country in Eurovision. While “Wild West” – co-written with Einar Stef of Hatari, the Icelandic band that held up the Palestinian flag during the 2019 Eurovision final in protest of its being held in Tel Aviv – narrowly lost the contest, the bid sheds light on the contested politics of performing in such events.

Hailing from Jerusalem, Bashar has a longstanding commitment to music and Palestine. Son of Said Murad, founder of the pioneering Palestinian band Sabreen, his career started in 2015. It wasn’t until 2019 when he participated in Globalvision (the live-streamed concert in protest of Eurovision, Tel Aviv) that he attracted global attention. Soon after, Bashar released his first EP, Maskhara (2021), which included the viral track “Antenne” produced in collaboration with Palestinian hip-hop icon Tamer Nafar. He’s continued to gain momentum since, singing the closing track for The Gaza Weekend (2022, dir. Basil Khalil), releasing his second EP, Nafas (2024), and dropping new singles from his yet-to-be-released debut studio album, most recently “ITSAHELL.”

In this interview, Bashar talks with Elias Jahshan about his Söngvakeppnin experience amid the Israeli genocide in Gaza; the role of language in his music; and why he rejects essentializations of him as a queer Palestinian artist.

[This interview was edited for brevity.]

Full fit; Christian Ye. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer.

How did you, a Palestinian, end up performing in Söngvakeppnin?

In 2019, I connected with Hatari, who participated in Eurovision in Tel Aviv with the intention to make a political statement. We stayed connected, released the song “Klefi/Samed” together, and performed together a few times in Iceland and other countries. That whole time, I kept thinking of Palestine in Eurovision and the legacy of my parents. [They led a campaign to include Palestine in Eurovision in 2007.] I was in Jerusalem at the end of Covid and I messaged Einar to ask if you have to be Icelandic to participate – we learned that the performer’s nationality doesn’t matter, but at least two-thirds of the songwriters must be Icelandic. He immediately got the hint and was like, shall we write a song?

I flew to Iceland. We were only planning to work on one song, but had amazing chemistry in the studio and ended up working on a whole album. One of those songs was “Wild West” – we wrote it in May 2023, and I submitted it for Söngvakeppnin in August.

I always try to find different avenues and platforms to project my voice, and it was important to show why a Palestinian needed to go to another country for the chance to compete in Eurovision [though “Israel” is technically included]. I wanted to highlight the many obstacles we face because we’re excluded from many mainstream platforms. Palestinians don’t have the opportunity of showing their art, culture, and everyday life that those in other countries do.

Can you say more about the Söngvakeppnin experience, especially considering that it took place amidst the Gaza genocide?

It was one of the most memorable experiences of my life, but at the same time, it was very surreal and conflicting because of the context. The plans were already in motion – I had submitted my song, had meetings with the TV network – and then October 7 happened and everything suddenly changed. My entry became extremely politicized before it was even public.

My passion is music, art, and performance. In one sense, I was doing what I love – to create a three-minute song using fashion, music, visuals, dancers, and my voice – but in the worst context. And there was always this feeling of guilt, because I get to live my life and my dream but when I open my phone, I see news of the Flour Massacre and other horrors.

This was a genuine intention, and I felt that my presence as a Palestinian with a dream and a voice was important. I’ve lived under occupation for 30 years, and I’ve been radicalized to want absolute freedom. I’m trying to achieve this using tools the universe has given me: my music. I want to break stereotypes and show that the Palestine we are dreaming of is not a monolith, it’s diverse. I’d have felt differently if I’d decided to compete after the genocide had started.

Zionists hate to see us thriving, and they hate to see us as humans or people with dreams. They want to see it as thugs, terrorists, shredded limbs, and gore, to kill our voices and silence us. Their reaction to my participation motivated me and reassured me that I was doing the right thing.

Hoodie; TOO DARK TO SEE TOMORROW. Skirt; Trashy Clothing. Shoes; Untitlab. Glasses; Balenciaga. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

Less than a week after you came runner-up in Söngvakeppnin, Israel’s song entry for Eurovision was officially accepted. Their first two submissions were disqualified for lyrics being “too political,” and calls to boycott Eurovision intensified after their third successful attempt. If, hypothetically, you had won Söngvakeppnin, how do you think you’d have navigated that?

This is an answer that we will never know. I never saw participating in Söngvakeppnin as a problem because it was a local Icelandic competition. At the core, I believed what I was doing was a form of protest. My presence created so many problems with Zionists and so much discussion, and that was just in Iceland. I think that being in the actual Eurovision competition would’ve had a huge impact, but I understand the pressure could have gotten to me.

And honestly, when I didn’t win Söngvakeppnin, I had a sense of relief. I was like, okay, so now I don’t have to deal with anything. I got to perform, piss off Zionists, and then left. I did what I needed to do.

Explain the concept behind “Wild West.”

It was all intentional. I wanted people to think, why is a Palestinian singing country? It’s about a person who makes it to the West with this big dream, but once there, nothing is what it seems. It’s a commentary about the West and how anyone who’s not from there is demonized, but at the core, it’s about dreams and yearning to be free from boundaries and borders.

I should also add: I released my song before Beyoncé released Cowboy Carter. [laughs]

Dress; EMERGENCY ROOM. Shoes; Untitlab. Wig Hat; Christian Ye. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

Is there a reason behind your shift from Arabic to English in your songwriting?

I only wrote in English when I was younger, and started writing and performing in Arabic after college, after coming home and living life in Palestine. I did this for years, but shifted to English with the idea of participating in Eurovision. It reopened my world.

When I was singing in Arabic, my audience was my people and I talked about internal things: internal frustrations (including the Occupation) and also the social things we go through as a community. In English, I address a wider audience and I have the opportunity to talk about things that haven’t been talked about, especially in [global] pop music.

Your Maskhara era sounds so different to the darker Nafas era. Why?

My music is always a reflection of how I’m feeling, and sometimes a reflection of the times. The Maskhara era was about turning ugliness into beauty and dressing up this harsh reality. I was also into the concept of protest and resistance taking many forms, and the need to penetrate all spaces and disrupt everything. That includes pop music and the dance floor. Just imagine the power of performing “Intifada on the Dance Floor” at some festival in Europe.

But with Nafas, I couldn’t do that anymore. I couldn’t keep dancing. “Ya Lel,” for example, I wrote after Israel’s assault on Gaza in August 2022 – I had the hook for years, but developed it at that time. It was about reality being so brutal that you can’t even look at it anymore. It was a reaction to seeing our own people being dehumanized and murdered. It also came after a time of having some hope. The Sheikh Jarrah protests brought hope that change was coming, then it was squashed. Hope was killed so quickly.

Left: Shirt & trousers; EMERGENCY ROOM x SILIQONE. Shoes; Untitlab. Right: Dress; Céline Ching. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer. Makeup by Tamara Hanna.

Your latest single “Stone” not only samples music from Sabreen, it also features a soundbite of Ghassan Kanafani talking about Palestinian freedom from a famous 1970 interview.

Yeah. I always wanted to sample a song from Sabreen, but I was very cautious because Sabreen’s music is what I grew up on. It means so much to me, and I really wanted to introduce it to a younger generation, within my art.

I gave Einar a couple of songs, and the sample he used led to “Stone.” We had come up with the concept early on and what it symbolizes for Palestinians: our homes, our land, the struggle, the apartheid wall, and more. Some parts of the song are sad and depressing, and others are beautiful and hopeful. That’s really our experience: it’s hope and hopelessness, like a ride that we can’t get off of.

And including Ghassan Kanafani’s words, with that specific quote – a hunger for freedom is really the mission statement in all of my music. I also don’t think there’s a lot of Palestinian music in English that talks about the struggle.

Full fit; Christian Ye. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer.

As a queer Palestinian artist, you’re politicized for being queer and for being Palestinian, not to mention the pinkwashing. How do you navigate that?

I don’t. [laughs] I live my life the way I want to, but obviously, it’s a lot to think about. Sometimes you’re put in a spot where you have to choose one identity over the other, and to me, I don’t think of any identity as separate.

But it affects the way I talk about these things, because of all the pinkwashing and how our identities are weaponized against us as queer Palestinians. I always know how my words will be used against me.

I’m just sick of occupiers and murderers coming to school us about what freedom means. I think that the Occupation and its pinkwashing tactics are actually creating more homophobia. They are so closely associating the queer identity with the rainbow flag and Israel. But this is a dated strategy. The timer on pinkwashing was running out even before the Gaza genocide started, and everything they’re doing now has been like the nail in the coffin. It’s like, Thank you for illustrating it. Now we don’t have to talk about it, because you’re just showing us with pictures.

The Zionist entity has been suffocating Palestinian society, the Palestinian people, Palestinian culture for a long time. Our identities have become this constant smoke screen to distract and to take the conversation somewhere else. I’ve reached the point where I don’t even want to engage in these discussions of trying to prove why we are worthy of not being murdered on a daily basis.

Full fit; Christian Ye. Photography by Mohsen Othman. Styling by Wassim Lahmer.

When people label you a ‘queer Palestinian artist’, do you find that a blessing or a curse?

I’m many things. I’m Palestinian, I’m queer, I’m an artist, but I’m also many other things. But those identities specifically are highlighted because there’s a need for them. It’s necessary to be visible.

Yet at the end of the day, I don’t even like the label of ‘queer artist’ – I prefer ‘Palestinian artist’. Palestinian is something that brings me pride, and when your identity is under attack, when it’s under constant denial, you want to claim it even more.

But I still don’t want to be pigeonholed. I’m aware that ‘Palestinian artists’ is now a buzzword and it’s benefiting a lot of people. But there’s a genocide. Yes, I am Palestinian, but I also don’t want to take advantage of that, or the cause.

I want to penetrate spaces because of my talent – not because of labels. My music may reflect my identity, but ultimately I want to be appreciated for my art.

Bashar Murad’s new single “Itsahell,” from his forthcoming debut album, is out now.

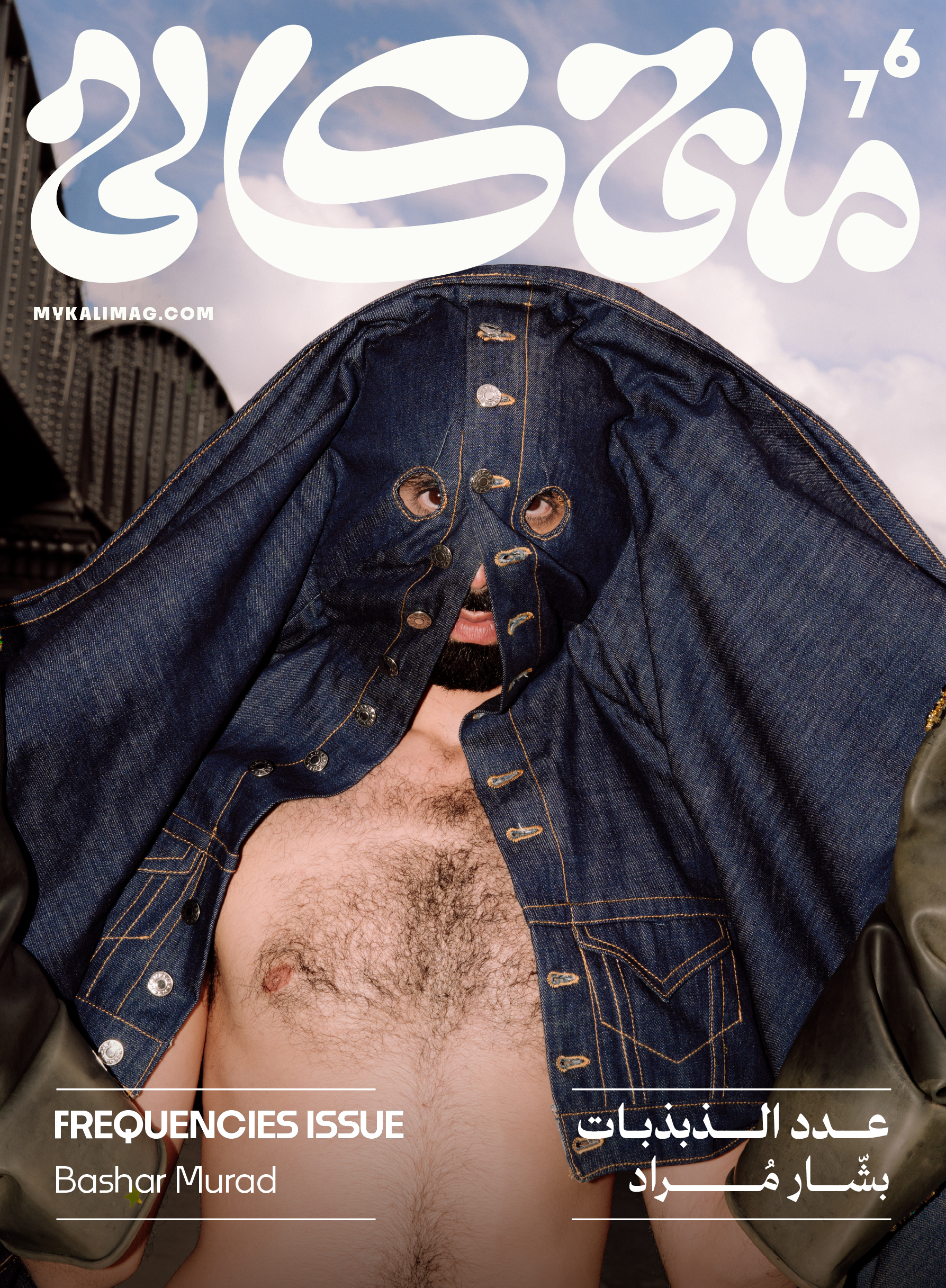

On The Cover

On the cover: Bashar Murad

Photography by Mohsen Othman

Styling by Wassim Lahmer

Makeup by Tamara Hanna

Stylist assistance by Marie Khx

Interview by Elias Jahshan

Cover design by Morcos Key

Cover design assembled by Alaa Sadi

Editor-in-Chief Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue