Words and artworks by Laila Demashquieh

Introduced and facilitated by Eliza Marks

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

What happens when we look more closely at coalescence and divergence, at processes and fluxuations, at textures? What do we feel? What starts to unravel? What new might come into frame?

In what follows, Amman-based visual artist and arts educator Laila Demashquieh discusses the deeply-personal production and curation of The Space Between Spaces | ما بين الثنايا. Engaging topological processes of erosion, fragmentation, collision, and formation, the collection of black-and-white monoprints draws a dialog between the delicate and the bold, demanding viewers to critically engage with not only the forms before them, but the world they live in. Discussing her ever-evolving practice, her approach to creating holistic and sensory exhibition spaces, and where she believes the power of art lies, Laila encourages us to imagine what an ecosystem that encourages artistic risk-taking and a plurality of ideas might look like.

To start, can you introduce yourself and share a bit about your background? How did you find your way into visual arts?

I am Laila Demashqieh, and my experience through the world of art spans almost two decades. So far, I’ve explored a diverse range of mediums, with a special emphasis on printmaking, etching, lithography, and, most recently, mixed media.

From the earliest days of my childhood, I’ve been utterly fascinated by art. The allure of colors, shapes, and the boundless space for imagination drew me in like a metaphysical force. Growing up, I often found the real world to be somewhat dry and discolored, particularly in light of the inevitable suffering it carried. In art, I discovered a sanctuary where my mind was free to flourish, where I could infuse the mundane with enchantment, and where I could breathe life into the seemingly lifeless. This enduring fascination with the transformative power of art has been a guiding force throughout my journey, motivating me to explore its many facets and harness its potential for both personal expression and positive change in the wider community.

Beyond my artistic pursuits, I have spent over a decade as an art education and community development specialist, working at various schools as well as in the non-profit space. Most recently, I am privileged to have co-founded a community development initiative called Alolbah, in partnership with the remarkable Jordanian artist Rand Abdulnour. The core mission of this initiative is to bring art back to the people — to mainstream essential artistic and creative skills through easily accessible and premade kits.

How would you describe your early work, and were there any key experiences or events that led you to start working toward producing a full exhibition?

My early work in art can be described as a journey of self-discovery and exploration. It was deeply influenced by my fascination with the interplay of human connections and the way our past shapes our present. I often sought to use the power of art to unravel the intricate threads that make up our personal histories and identities, which also meant that my style underwent significant evolutions throughout.

The culmination of both my personal and artistic growth led me to host a full exhibition. I realized that my vision had evolved and matured, and it demanded a more comprehensive platform for expression. This was reinforced by the feedback of trusted friends and mentors who witnessed the development of my work within my studio and saw the potential for a coherent and powerful artistic statement.

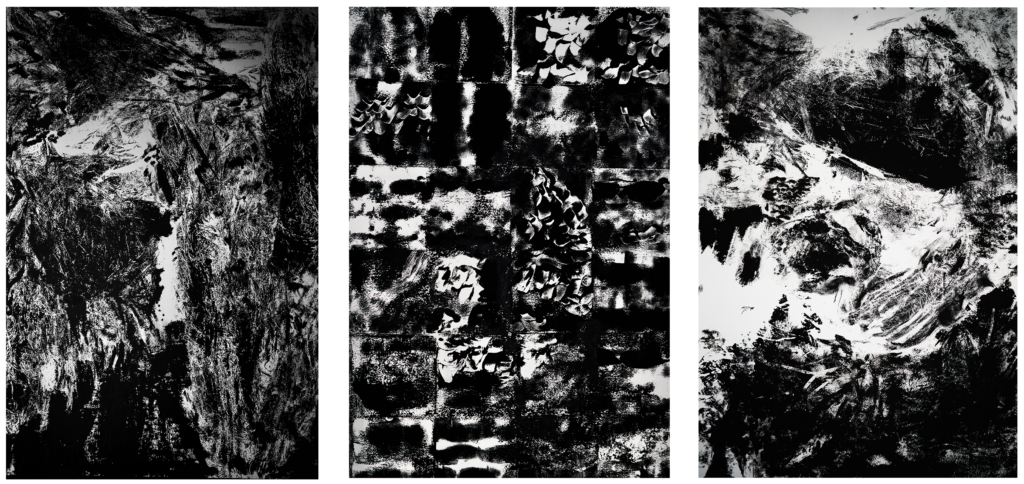

Formations 8, 6, and 7

Two years ago, I began the body of work that later became The Space Between Spaces, which was born out of my fascination with the perpetual state of flux that defines our lives. This concept, which has captivated humanity since we became self-aware, resonated deeply with me, and it demanded intensive research, experimentation, and emotional introspection. As the body of work began to take shape and coalesce into a unified narrative, it became clear that a solo exhibition was the ideal way to present the complete experience to a wider audience.

The decision to exhibit this body of work marked a significant milestone for me, as I’ve always been averse to the spotlight. It allowed me to delve deeper into the themes that had always fascinated me, while also pushing the boundaries of my creative process. It was a transformative experience, not only in terms of artistic expression but also in terms of personal growth and self-discovery.

The exhibited works were supported by a very intentional design from start to finish – from the creation of the visual identity to the limited-edition booklets and supporting papers, to the space itself to the sound that filled it. How did you envision each of these elements/details that play in supporting your work?

Upon the completion of the body of work, a paramount concern emerged: how to convey the exhibition’s essence effectively and comprehensively to every visitor, including those who may not have much experience with art, starting from the very moment they set foot in the gallery. At the heart of this endeavor lay the holistic comprehension of the viewer’s experience, which revolved around the very gallery space itself.

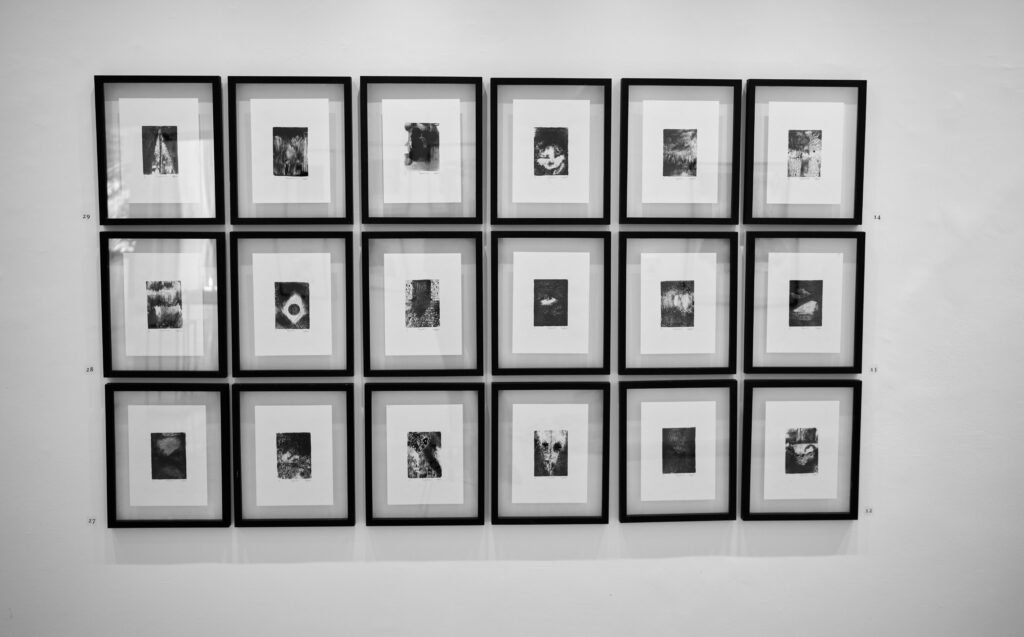

Extensive care went into curating this exhibition, with the aim of allowing visitors to grasp a key concept in the overarching narrative: the idea of emptiness. Foresight Gallery, recognizing this vision, generously allowed me to adapt the space to complement the artwork. The viewer’s journey began upon entering the gallery, guided by strategically placed wall text directing them to the heart of the exhibition, which was divided into four main sections: Erosions, Fragments, Collisions, and Formations. To enhance the emotional impact, we also included a carefully curated playlist that guided viewers through an immersive and sensory experience. It was also essential for me to incorporate graphic design into the experience, which is also why I partnered with Eyen to help create some of the branding and marketing materials for the exhibition.

More importantly, the exhibition was designed to engage all the viewer’s senses, with every aspect thoughtfully curated — from the renovation of the space to the selection of background music, down to the precise placement of each item on display. The result was an immersive environment that enveloped visitors while subtly disorienting them. This comprehensive approach encouraged viewers to wrestle with the abstract nature of the concept behind the artworks, fostering a deeper connection between the observer and the exhibition’s central theme.

The pieces are jarring in some way, moving beyond the “art-as-beauty” impulse to also invoke something from the viewer. Was there a specific thing you were trying to make the viewer feel?

Throughout the annals of history, art has served as a powerful instrument for documenting, preserving, and interpreting our intricate relationship with the world. My primary objective was to encourage viewers to embark on an introspective exploration as they engaged with each piece, delving deep into their own perceptions. I aimed to prompt them to scrutinize the works, to unravel what lay beneath the surface, and to contemplate the collective unconscious that gave birth to them. This intention was driven by a desire to challenge viewers to question their preconceived notions and perceptions, and to beckon them to examine the memories, experiences, and emotions stirred within them by the encounter.

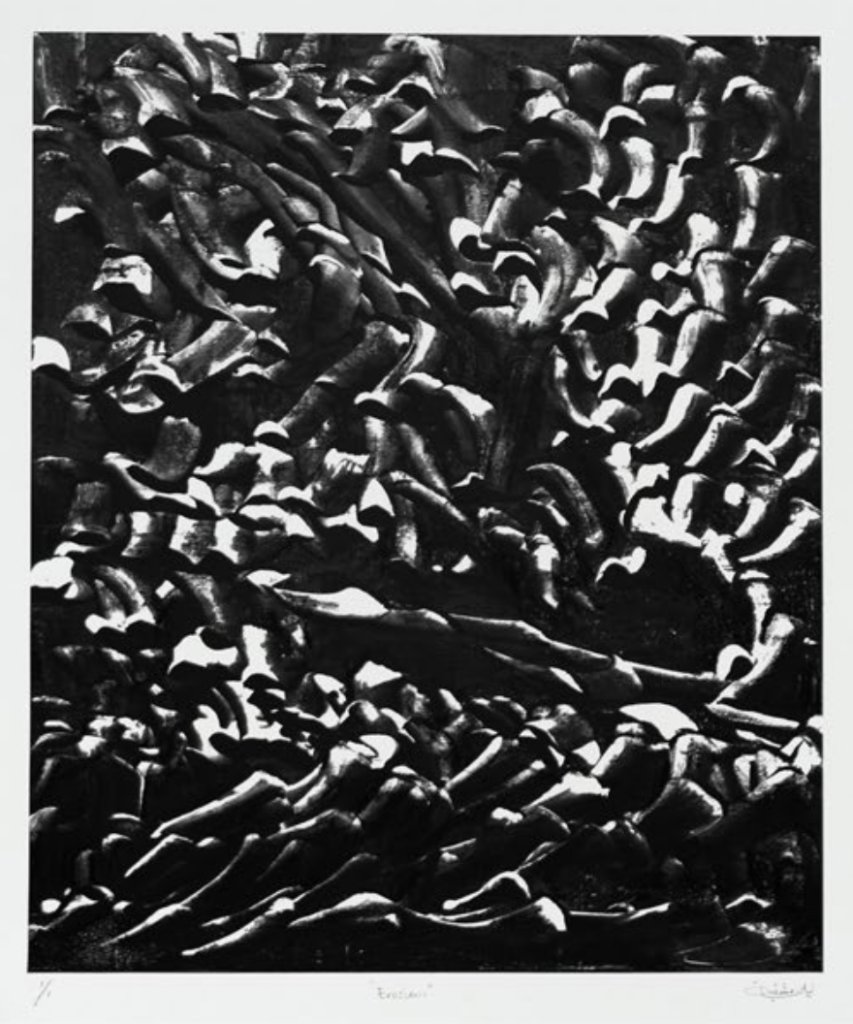

When I was an undergraduate student of fine arts, a professor characterized my art as “ugly art.” I felt both challenged and intrigued, and I pressed him for an explanation. He likened the lines in my work to bold and assertive strokes that often subvert conventional expectations, especially given the darker and monotone color palettes I tended to prefer. There, I was, confounded by a blunt characterization coming from a teacher with a longstanding and academic background, where the most celebrated works often featured delicate female subjects who conformed to prevailing standards of beauty. It profoundly influenced my artistic development and educational philosophy, pushing me to explore the boundaries and conventions of what is considered ugly and beautiful in art. It awakened me to the rigid shackles that tradition places on our perceptions, and made challenging norms a cornerstone of my creative development.

Erosions VIII

This experience also sparked a deeper exploration into the historical context of beauty in art. Throughout history, the concept of beauty has been redefined numerous times. For instance, the Renaissance ideal of beauty, epitomized by artists like Botticelli and Raphael, gave way to the more dramatic and emotionally charged works of the Baroque period. Later, the Impressionists challenged academic norms by focusing on light and color rather than precise representation. Then came the early 20th century, which saw further radical shifts with movements like cubism and abstract expressionism, which completely departed from traditional notions of beauty. Artists like Frida Kahlo and Helen Frankenthaler created works that many initially found jarring or unconventional, but which came to be celebrated for their emotional power and innovative approach. Kahlo’s raw, unflinching self-portraits challenged societal norms of beauty and femininity, while Frankenthaler’s bold, abstract color field paintings pushed the boundaries of artistic expression.

Understanding this historical context helped me appreciate that my professor’s view, while rooted in a certain tradition, was part of a much broader, ongoing dialogue about aesthetics in art. It encouraged me to push boundaries and explore new territories in my work, rather than confining myself to conventional standards of beauty. I tend to agree with John Keats’ famous statement, “beauty is truth.” If a work of art captures a genuine experience, it carries an inherent beauty that will resonate with viewers, even those who may not be inclined to its particular style.

This evolution has not only influenced my artistic practice but also my approach to art education. I strive to encourage students to question established norms, to find beauty in unexpected places, and to understand that art’s power lies not just in its aesthetic appeal, but in its ability to provoke thought, emotion, and dialogue.

Something else that really set this work apart is how you made it accessible to those who were not able to attend the exhibit in person through Instagram – the various posts and videography let viewers get a sense of your process, the exhibition space, key works, etc. How do you imagine these two ways of exhibiting your work – in physical space and digital space – compare or support each other? How did you curate these experiences differently?

I find this question very interesting, as the primary objective of the digital content I curated was to encourage audiences to experience the work in person. During this process, however, it became clear that incorporating a digital media component into the process allowed for certain aspects of the work to shine through, particularly the finer details in some of the artworks. After all, the very nature of ink is organic and mercurial, particularly when it comes to the way it seeps into the finer grains of the medium to create something beyond what was intended. When viewed at the different angles and focal lengths allowed through photos and videos, the shapes coalesce and diverge to give various impressions, all colored by the viewer’s subconscious and brain chemistry.

Ultimately, I came to regard these digital products as extensions of the overall experience, and while I believe this body of work is best experienced in person, there is something to say about the opportunities digital platforms give artists to showcase their work and re-discover it in the process.

Amman can be a tricky place to produce this kind of work that encourages critical engagement. This sort of experimentation does not seem as widely accepted in the current art world, and there is a limited number of galleries willing to invest in this style. After having produced and exhibited your first collection, do you have any reflections you can share with others who are trying to do this sort of work in Amman or in the region, more generally?

When I began creating this body of work, I had some initial hesitations about how it would be received. These hesitations weren’t so much about the art scene in Amman or the Middle East, which has its own rich history of innovative artists, but more about the specific nature of my work. The use of dark palettes and the abstract exploration of emptiness as a concept felt like a departure from what I had previously seen exhibited. I was aware that my work might be challenging for some viewers, not because of any lack in the art scene, but simply due to its introspective nature and the demand it places on the audience to engage critically. Art that requires this level of engagement can be demanding in any context, regardless of location.

However, I was fortunate to have the support and encouragement of various trusted individuals and mentors who recognized the originality of the work and the concept behind it. Their belief in the project was pivotal in motivating me to exhibit it. From this experience, I’ve learned that if you have a well-developed body of work, underpinned by a concept supported by research and a clear vision, the right opportunity will eventually present itself. I also believe that artists should feel empowered to present work that resonates with their artistic vision, as this contributes to the diversity and richness of the art scene. In Amman, and across the region more generally, there are galleries and institutions that are open to diverse forms of artistic expression. It’s about finding the right match and timing for your work.

What do you think individuals or cultural institutions/initiatives/entities can do to support the growth of such projects? What shifts in context could allow for the cultivation of such works?

Supporting art projects that challenge traditional values or embrace non-traditional approaches in Jordan requires a multifaceted approach. One fundamental area for improvement is art education in public schools. The current curricula being taught throughout the kingdom often relegates art to a supplementary and less significant domain, and doesn’t fully encompass contemporary art practices, limiting young people’s exposure to diverse forms of creative expression.

Our cultural institutions could play a significant role in addressing this gap. Partnerships between these institutions and schools, offering workshops or residency programs, could bring practicing artists into classrooms. This would provide students with firsthand experience of various art techniques and ideas that push boundaries. Galleries and museums could also contribute by embracing artistic diversity. Dedicating more space to works that challenge conventional norms, even if they’re not guaranteed crowd-pleasers, would provide artists with a platform and help broaden public perception of what art can be.

Funding also plays a critical role in supporting innovative art projects. While some funding opportunities may exist, there appears to be a communication gap, with many artists unaware of some of the resources available to them. This gap can hinder the growth and development of non-traditional art forms. Private individuals and businesses have been instrumental in providing grants for innovative art projects, but the inconsistent nature of this funding presents challenges. A more structured approach to communicating existing funding options and potentially establishing new, sustainable funding sources could significantly benefit artists exploring new territories in their work.

Jordan does have some spaces for artistic collaboration, but these could be further supported and expanded. Government allocation of more funding to help these spaces thrive could enhance their potential. These collaborative environments, whether simple community centers offering studio space or complex interdisciplinary art labs, allow artists to share ideas and resources, potentially leading to more groundbreaking work.

The incorporation of diverse forms of public art into urban planning has been attempted by local governments, with thought-provoking sculptures and installations occasionally appearing in public spaces. These initiatives have shown the potential to make art a part of everyday life and expose the public to new artistic concepts. However, the inconsistency of these efforts has limited their long-term impact. A more sustained and systematic approach to integrating public art into urban landscapes could foster a greater appreciation for diverse artistic expressions among the general public.

Most importantly, in a region currently being ravaged by war and other forms of political instability, art can be seen as a luxury that is completely disconnected from the realities of the masses. However, historically, art has been a vehicle for powerful sociopolitical transformation and must be supported as such, particularly in our region.

These changes require time and collective effort. Creating an environment where artistic risk-taking is encouraged and new ideas can flourish, while still respecting and building upon our rich cultural heritage, is a lengthy and often frustrating process. It requires fostering an ecosystem that supports, values, and integrates diverse forms of expression into the very essence of our society’s cultural identity and daily life.