Words by Nour Shtayyeh

Translated by Hiba Moustafa

Transcribed by Nour Shtayyeh

Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar

Styling by Samer Owaida

Makeup and hairstyle/design by Mouna Tahar

Shoot assistant: Ivana Jarmon

Featured image styling credits: Pearls; Vitaly. Orange cardigan; Savage X Fenty. Skirt; Gypsie blu. White top; artist’s own.

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

Music has historically been one of the many forms through which spirituality is experienced, expressed, and shared with others. Centered around elements of healing, storytelling, and expressions of the self, music, and spirituality become intertwined: the musical breeds the spiritual, and the spiritual inspires the creation of the musical.

Egyptian-Levantine artist Mirza Shams, also known as NAXÖ, thoughtfully weaves these elements together through their musical creativity. As a queer, non-binary multidisciplinary producer, composer, sound healer, and multi-instrumentalist, NAXÖ works across genres, fusing Middle Eastern folklore with electronic psychedelic to highlight themes of queerness, migration, and postcolonialism. NAXÖ released their first album, Tesa’a, in 2021, after moving to Chicago from their hometown in Egypt. Now, they continue to use their voice to convey the importance of being true to one’s self and build experience through the healing power of music.

In this interview, NAXÖ speaks about their identity and relationship to spirituality as inspiration for making music, challenging oppressive notions of queer and Arab identities, using language as a tool for liberation, and forging a path for the marrying of politics and liberation. The text has been edited for brevity.

To start, can you tell us a little bit about yourself: your background, upbringing, and how you got into music? What is the significance of the name “NAXÖ”?

I am a queer, non-binary multidisciplinary sound artist and musician. I was born in Egypt and grew up in a very dysfunctional family due to all kinds of distortions that they had held onto. I was forced into parenting myself because my parents weren’t even available for themselves, so how would they be available for me?

I recognized that at a very young age because of piano. I started playing when I was seven, and experimented with a lot of genres, including Eastern classical, Western classical, jazz, blues, electronic, rock, and metal. It became my best friend and helped me unfold parts of myself and provided me with a space that neither my parents, school, friends, or neighbors were able to.

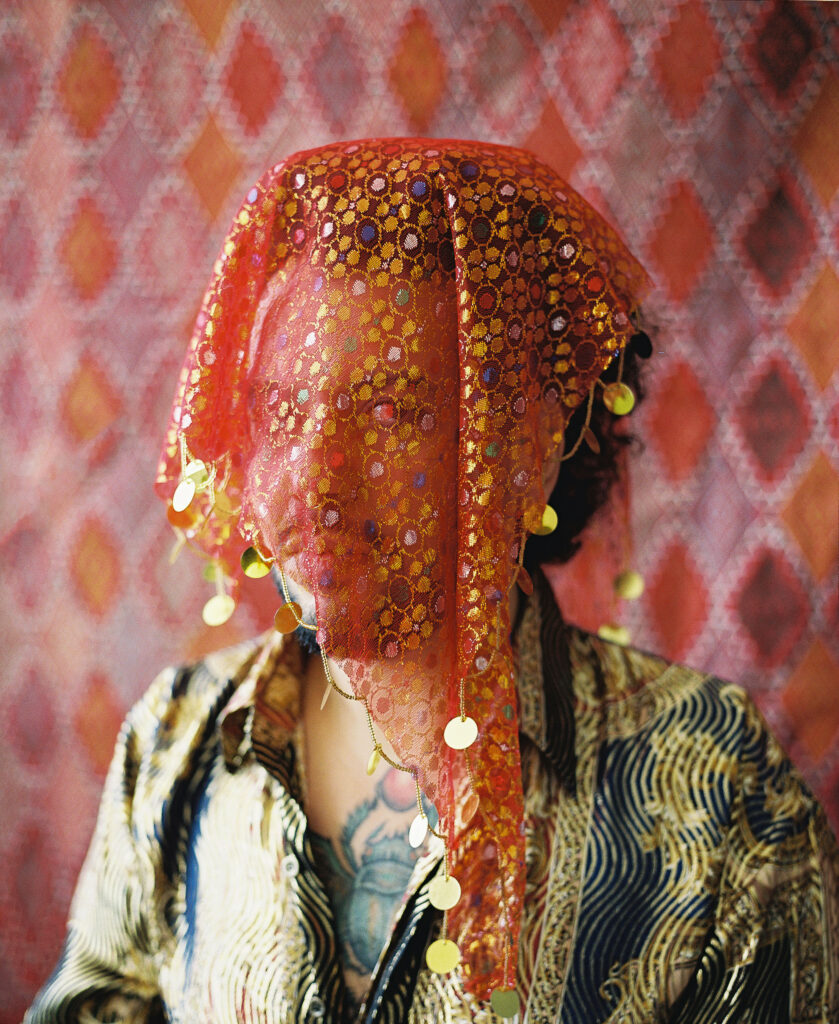

Top; Vintage Onyx. Scarf; stylist’s own. Rug; Tunisia. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

NAXÖ is an amalgamation of multiple meanings. The name is gender-neutral, conceptual, and an embodiment of the queer psyche. It is a reference to embracing the shadows of love practices in a world where the good is bad, and the bad is good. It’s about queer love and pride in our expressions of care, both as I reclaim my queerness through music and try to contribute wholeheartedly to our collective queerness and trans-ness. Another layer is that it’s an abbreviation for “Non-Applicable Hugs and Kisses.” It is pronounced as NAXOH or NAXAH – نكسه.

How did music help you through the journey of self, identity, and unfolding those different parts of yourself?

As a queer person growing up back home, it was very hard for me to explore who I was and exercise my voice, especially in musical spaces. Many musicians and bands were interested in what I had to bring to projects, but outside the studios and stages, there was an incredible amount of homophobia and transphobia. I loved singing because it allowed me to express myself, but I realized I was kind of hiding it and keeping it to myself.

Eventually, it reached a point where I couldn’t hide it anymore, it just had to come out of me. Moving to the United States was such a critical time in my life, because I stopped compromising anything of what made me me. Part of that was being able to sing about whatever I wanted to sing about; I wanted to sing about my lived experience, about reclaiming the parts of my culture that had been hindered or erased.

Like so many people back home, I know how much we are deprived of sexual and gender education and spiritual education outside of Islam. Everything had to be coming back to Islam, or back to “tradition.” I feel like, as much as Islam and tradition are integral to what makes our culture nowadays, I also can’t avoid the fact that interpretations and projections of understanding these have led to all kinds of toxicities, and have contributed to a society that is very traumatized. It’s not only by colonization, the government, and political turmoil, but also by themselves. Many are living a heteronormative, conservative, traditional existence, undergirded in deep trauma and disconnection from self. They are really struggling to root into their authenticity as human beings.

So I wanted to dive back into my ancestry, my own queer and trans heritage that I had not really had access to in this context. I started diving deep, from the inside, and it’s been a journey. Music was my first instrument, and my voice became the second.

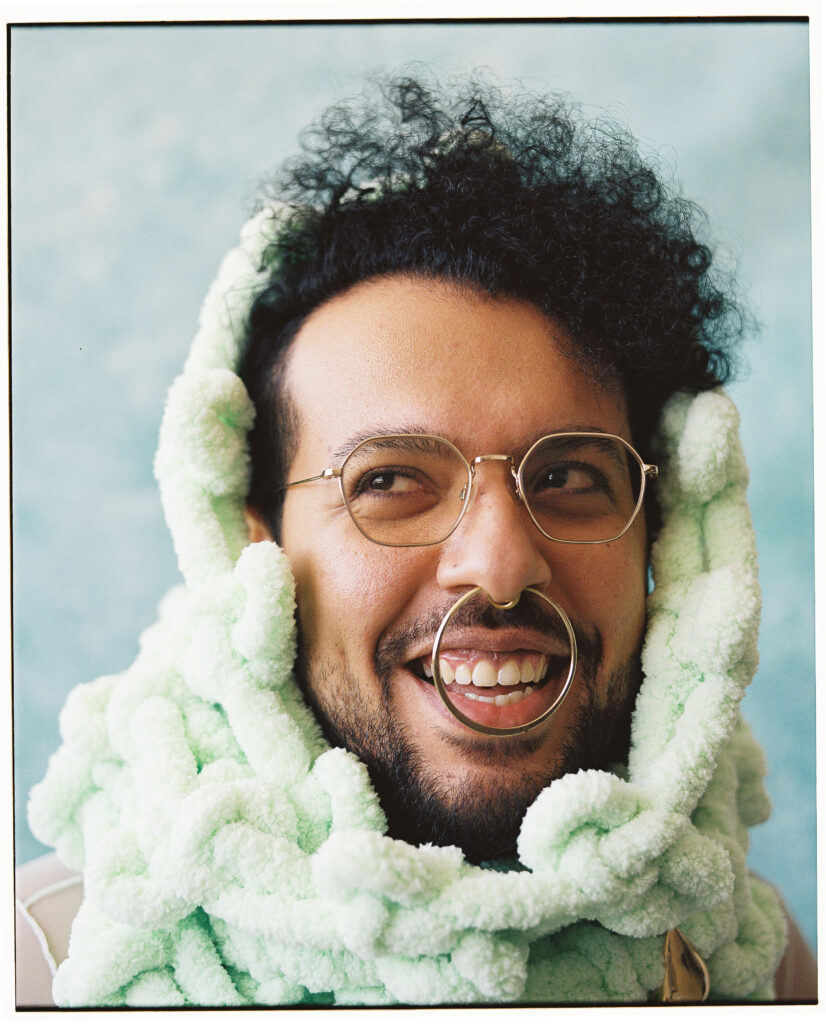

Jewelery; Sayran. Jacket; Yasmine Ali. Kaftan; Devarshy. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

My first song talked about khawal. It emerged out of years of being bullied on the streets, daily, for being who I was. I really felt my most creative self making this project and just going hard for it, saying it like it is. So that’s a little bit about how my music intersected with my sexual and gender journey.

Your songs have some really powerful themes on visibility, (dis)appearance, seeing, and being seen. How do you select and organize these themes throughout your albums and music?

I first picked a few songs, which represent the album’s main elements. I knew it’d be challenging, but also one rooted in parts that I had disconnected from. I started with “Khawal” and a few other songs. One of them is called “Mashtyhoesh,” and the other is called “A’aib.” It began with me just expressing my full self, then I realized a concept was coming together from different angles.

It was the same time as my transition and migration. When I migrated, I had this legal status of “asylum seeker” that I was confined to. The album was based on sexual, gender, and spiritual discrimination, because I come from a Muslim background but am not necessarily a regular Muslim. I have my own thing, a deconstructed spiritual practice that makes sense for me. And the journey, what inspired it, was always rooted in the values and beliefs that aligned with my purpose, mind, soul, heart. This whole journey was about searching and grounding in myself. I kept composing and writing, and it came together organically. I wanted to bring the sound into a place that represented where I was during that time period.

My fate number is also nine, and I connect with it in so many ways. So I began seeing a theme, which is Tesa’a, the name of that first album. It represents the number and the search.

As a sound healer, can you tell me more about this intersection between music and spirituality? How does that feed into the values that you are trying to communicate through your work?

The number nine is the transition into double digits, like the end and beginning of two different chapters. I connect numerology with astrology. My sun is in Taurus and my rising is in Pisces. On the zodiac spectrum, these are the beginning and the end. Pisces are the last in the cycle; they’re the elders with wisdom, who have seen it all and know how to break the ice, and also in deep sorrow because of how much they know about the world. At the same time, the Taurus is very rigid, stubborn, full of life, all about spring, the sun, and big energy. It’s very different.

This album has been a major transition for me. I’m transitioning from being a musician who’s worked with so many bands, who are often homophobic and transphobic and have made me feel the need to silence myself, into doing solo projects and inviting other creators into my process. It allows me to root into my solitude. I know that where I’m going is different, so I feel like I’m moving into the two digits. I feel like I’m more joyous, more at ease, like I don’t have to run, but I can walk.

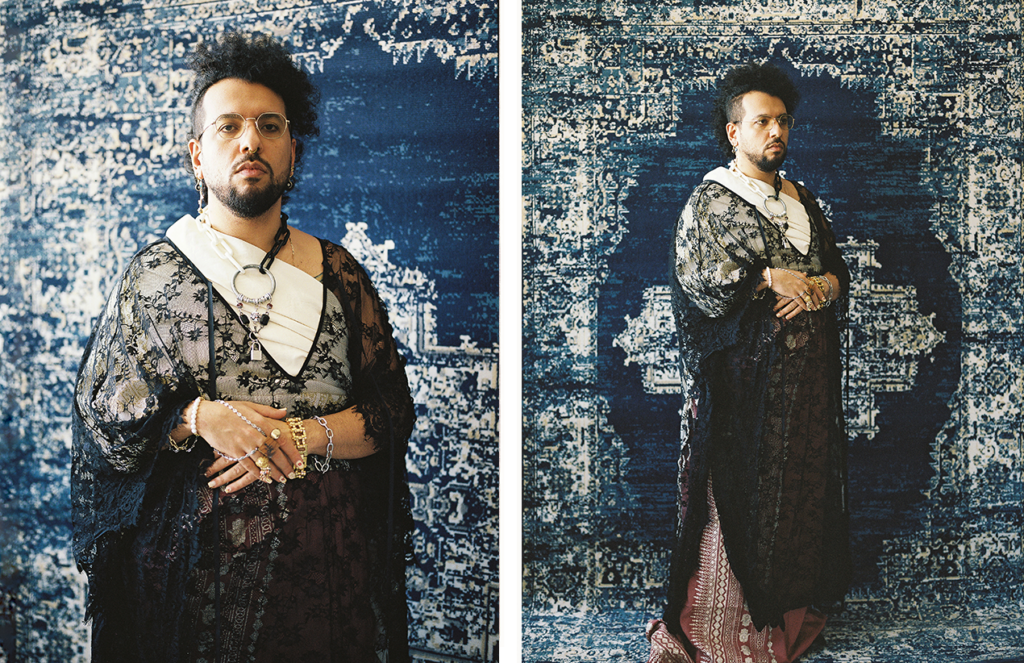

Heels; Syro Jewelry. Jewelery; Sayran. Purse; Kara. Jacket; Yasmine Ali. Kaftan; Devarshy. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

As for my values, liberation is a very important value for me that I center in my music, because we’re all hungry for it. If there’s one thing my people are starving for, it’s liberation. And there are so many types of liberation: of the mind, the soul, the heart, the body.

Another value is focus. It’s very important because we’ve been constantly distracted and displaced. When we are constantly experiencing these kinds of hardships, focus dissipates. Focus is a tool to help us remind ourselves of who we are, to continue growing into the parts that need to expand.

The third would probably be healing. We grew up in a culture that compartmentalized healing into the worst practices. For example, there are so many question marks around mental health. I center mental health in my music because I want people to understand that everything starts from the mind. It roots into the heart and soul, and there’s no escape from it. I speak the truth as it is because I have no filter, and sometimes people perceive it as rude. And this is interconnected with physical health. A lot of us “carry our issues in our tissues,” and it’s important to heal them in parallel.

In one of your songs, “Wogoudy,” you have an interesting lyric – “وطني نفسي وطني ليس مكان ولادتي” (tr. my homeland is myself, not the place of my birth) – which points to the tensions between the self, home, and nation. Can you say more about this tension, personally, and how they intersect?

When I was growing up, I was constantly told that Egypt is my home. And I love my land. I love Egypt, as nature, places, my friends, comrades, and communities that match my wavelength. But I know that my lived experience also included haters, aggressors, and violators of difference and authenticity. I recognized that I was in a state of limbo between belonging and not belonging, and that I actually don’t belong more than I belong.

I realized that I needed to protect my fullness and pour out of my cup. When I moved to the US, the part I disconnected from was the land, my watan. Home was not necessarily the people; it was the food, culture, land, friends and communities, which I was lacking in the US. Now, I carry these parts within me, and realize it was never about the outside that I’m interacting with, but the inside that I continue to carry. I can be who I am without fearing that the police would arrest me for being queer or trans. I can wear dresses and go out. I can now exist as fabulously as I want.

The dichotomy of my lived experience – as both soft, gentle, and loving, and as fierce and capable of standing up for myself – was very visible and non-normative. The more I exercised my queerness, trans-ness, and spirituality, the more I realized that I am my own home.

Scarf; Kara. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

That was one of the reasons why I wrote this song: I wanted to make a prayer as a centering mantra. “My existence is my existence, not your existence. Your existence is your existence, not their existence. Their existence is their existence, not your existence, not my existence.” I was trying to set boundaries through a centering thought, a hypnotizing prayer that goes back and forth and draws lines, instead of it being so chaotic and fused. I end it with the quote that “home is not where you are born, home is where all your attempts to escape cease,” because that’s what happens. People are running after home, but they are running away from everything to chase it. The moment you stop running away is when you are home, when you are settled and nested.

I would like to know more about the fusion of genres in your work, and the way you mix between traditional Arabic rhythms and electronic and psychedelic. Can you tell me more about that?

I grew up playing multiple genres. I wanted to come up with ratios of elements from here and there, creating my own sound and making something that really expressed my interiority. A lot of the music I play is music that isn’t necessarily rooted in our culture, but many rhythms are rooted in and derived from our cultures – Eastern and African. Blues and jazz, for example, draw on these theories and rhythms, and later, Western musicians traveled to our homes, learned the theories and rhythms, and then adapted them. It took a lot of playing and practicing to recognize the similarities and commonalities.

I love our music, but it’s very rooted in cis-heteronormativity and religion, and that made me rebel against it. I kept going back and forth until I realized that I can exist in both worlds simultaneously, without either fully representing me. I wanted to make something that is rooted in my Eastern culture and in navigating sounds and spaces.

Earrings; Sayran. Necklace; Yassin Adams. Shoes; J. Pearl bracelet; Vitaly. Dress; various draped fabrics from north africa, and levant. Black lace dress; vintage. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

I was also sad and mad when I was making that album. I wanted to portray that sense of fighting and resistance against everything standing in my way, but fighting it gracefully. I wanted to tell the world that we’re not the only ones, that there are so many of us carrying our light through the dark. And when we move, we leave parts of the light behind us, creating pathways. I also wanted to make something that makes people feel sexy, flowing through their curves, feeling their body, letting go and opening up. So, that’s how the fusion came together, from the sounds and the concepts and everything else.

You also play a lot with language and words in your lyrics. Is that something you do intentionally?

Yes! Because my music is basically psychedelic, electronic, Arabic pop. The psychedelic is not just rooted in the musical element, but in the songwriting itself. That’s why I like to play with words. It’s also a reflection of me somehow: I’m not only non-binary in my gender, but in everything that makes me me. Even my words. I want to show people that somebody can mean a word in one shape and context, but it could also mean something entirely different as well. It just depends on how you see it.

You’ve said that liberation is one of your core values. Can you speak more to the relationship between spiritual liberation and political liberation?

Politics has always relied on religion, and vice versa – they are so integrated. Stuck between religion and politics, political liberation is an essential part of the process of liberating our spirituality. We need to be able to tap into what politics makes sense for us, what politics contributes to our well-being. And, if someone’s spirituality isn’t right, often their politics isn’t right. If someone’s spirituality is beautiful, usually the way they navigate politics is also mindful.

Do you think there’s hope for the Arabic-speaking world in moving towards spiritual, sexual, and political liberation?

I do think so, because the future is ours and it comes from what we are doing in the present. We have more accessibility now. Our communities have been connecting more with who they are, outside what was offered to them. So I definitely feel hopeful. Even at times when I think I might not see it in my lifetime, when it feels as though we’re living in our own world, I realize that I’m not actually in my own world and that there are many other folks who are living similarly. Liberation might not be in our lifetime, but at least we have tiny bits of it that are growing and expanding.

Red top; Step In Style. Kaftan under top; Lapogee. Boots; Unisa. Jewelry; artist’s own. Photography & creative direction by Mouna Tahar. Styling by Samer Owaida. Makeup and hairstyle by Mouna Tahar.

Are there any projects you’re currently working on, or looking forward to in the coming period?

I have actually been working on a new album, which I’m really excited about. I released a single from it called “Something Blue.” The album has a different sound, a heaviness in the rhythms and tempos. It’s a low tempo album and has a lot of live strings sections. And it’s coming out soon!

On The Cover

Photos and creative direction by Mouna Tahar

Interview by Nour Shtayyeh

Cover design by Morcos Key

Cover design assembled by Alaa Sadi

Editor-in-Chief Khalid Abdel-Hadi

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue