Words by Musa Al-Shadeedi

Adapted from a chapter in The Return of the Colonizer to Youth

Chapter edited by Rola Al-Saghir, revised by Nazir Malakawy and designed by Noura Salem

Featured manuscript picture: The David Collection

Translated by Hiba Moustafa

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

This content may not be suitable for everyone 🔞

The David Collection has the biggest collection of Islamic art in Scandinavia and one of the largest in Europe. It was built around the private collections of lawyers, businessman, and art collector C. L. David. The manuscript contains 209, 22 x 33 cm pages dated 1779, 1780, and 1799. It contains 85 paintings that mostly depict varied sexual practices, ranging from group sex among a circle of men, sex with wild animals, to sex with blind people in a shrine. There are also paintings of women using dildos as they have sex with other women. They were all painted by Sheikh Muhammad bin Mustafa Al-Masry.

In this article, which is a chapter from The Return of the Colonizer to Youth, I will review the miniatures the manuscript contains to explore the idea that led to their creation and their function. I will also try to imagine the target audience and understand the context in which they appeared by reviewing the Arabic texts from which the parts of the Turkish-language manuscript were translated.

Due to the popularity of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish erotic literature at the time, many books, including this manuscript, started to include multiple translations. It is difficult to trace the source or author(s) of many of its passages, but, without doubt, an Arabic book that it contains a translation of is Ruju’ al-Shaykh ila Sibah fi al-Quwwah ‘ala al-Bah (The Return of the Old Man to Youth through the Power of Sex)1 by Ibn Kemal (1469–1534)2, which was translated into Persian and then into Ottoman Turkish. I found a worn-out, unauthenticated copy of the text on the black market; it’s banned by the government as a pornographic book. Ruju’ al-Shaykh is a sex education book that includes pharmaceutical herbal recipes to increase the penis size, tighten the vagina and improve its smell, and increase sperm; recipes for pregnancy and abortion; recipes that encourage lesbianism; and instructions for several sex positions. Most importantly, it was “Compiled and translated into Ottoman Turkish for the first time … for Sultan Selim I.”3 This connection indicates that authorities in the past, unlike local authorities now and Western ones in the past, funded lesbian and gay erotic literature and paintings.

This was not a rare case: Sheikh Nafzawi’s sex manual, The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight was compiled at the request of the Hafsid ruler of Tunis, Abu Faris Abd al-Aziz al-Mutawakkil sometime during the fifteenth century. In 1850, a French general took a copy with him from Algeria to Europe, where all its copies were confiscated and burnt by the Nazis for their “pure pornography”4 in 1939. In the 1990s, the Lebanese morality police banned and confiscated the book after a publisher in Beirut attempted to reprint the text. This has led to more copies circulating in the black market,5 including in Jordan, where I found my copy.

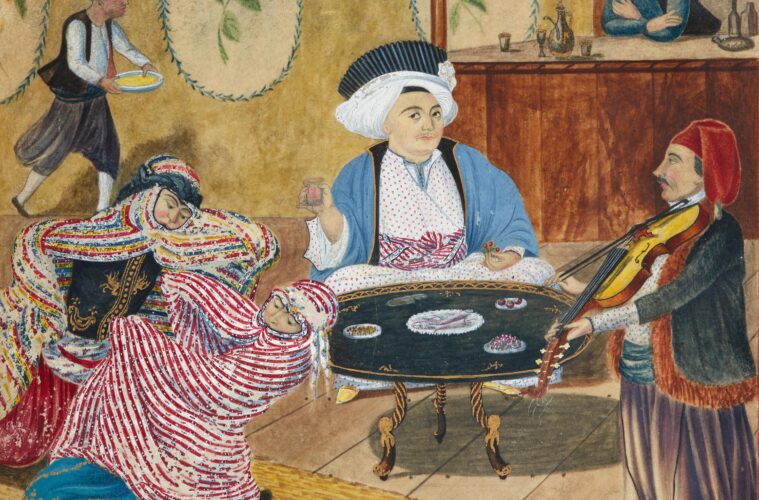

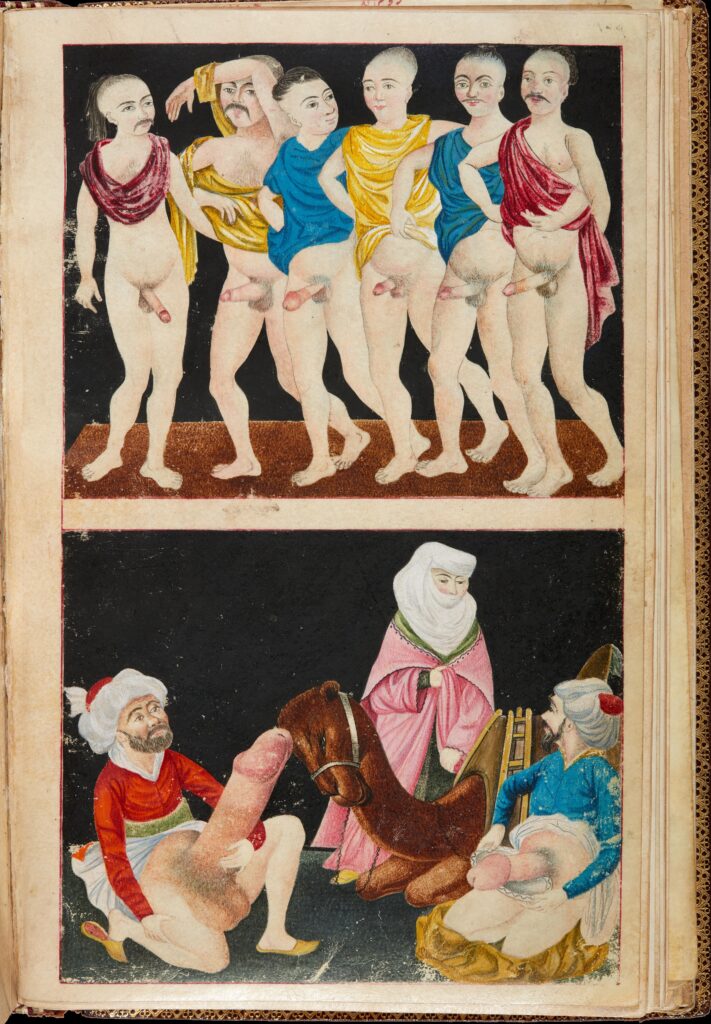

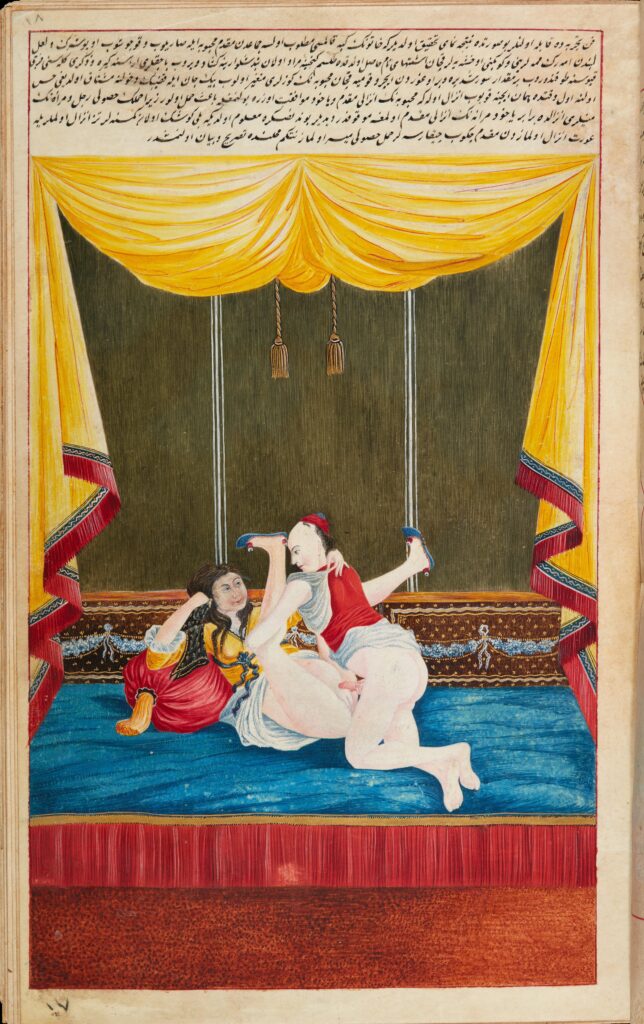

It seems that the manuscript, which was painted by Sheikh Al-Masry and included a Turkish translation, was also funded by an Ottoman courtier. The last page of the manuscript depicts a man in extravagant clothes and a court turban, holding a black handkerchief and a small bouquet of flowers, suggests the manuscript was made in his honor (Figure 1). The same man appears repeatedly in the manuscript’s miniatures. In one, he appears as an old man with a friend of his, a woman, and, apparently, a ghulam (boy) standing between them (Figure 2). The man is reaching out into the ghulam’s shirt, while his friend tries to get closer to the woman, as suggested by his posture and gaze at her. In another, he looks younger, sitting in a bar, while two young men dance and another plays music (Figure 3). And, in another, he looks even younger as he engages in a foursome with three young men (Figure 4). Such portrayals of him at different ages suggest that this manuscript represents his journey back to youth.

Figure 1: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 209r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 2: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 140r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 3: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 34r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 4: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 128r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

The most prominent feature of these books is their focus on sexual pleasure as an essential aspect of health, without reducing health to sexual organs in terms of efficacy or moral purity, as modern Western medicine does. A prominent example is Sheikh Nafzawi’s introduction to The Perfumed Garden,

Praise be given to God, who … has not endowed the parts of a woman with any pleasurable or satisfactory feeling until the same has been penetrated by the instrument of the male; and likewise, the sexual organs of man know neither rest nor quietness until they have entered those of the female.6

Describing Arabic-Islamic knowledge about sex as “ars erotica,” French philosopher Michel Foucault says,

On the one hand, the societies—and they are numerous: China, Japan, India, Rome, the [Arab-Muslim] societies—which endowed themselves with an ars erotica. In the erotic art, truth is drawn from pleasure itself, understood as a practice and accumulated as experience; pleasure is not considered in relation to an absolute law of the permitted and the forbidden, nor by reference to a criterion of utility, but first and foremost in relation to itself; it is experienced as pleasure, evaluated in terms of its intensity, its specific quality, its duration, its reverberations in the body and the soul. Moreover, this knowledge must be deflected back into the sexual practice itself, in order to shape it as though from within and amplify its effects.7

This is presented by Foucault as an antithesis to the way that repressive Victorian, Western culture has treated sex, and its development of the field of “sexology” [the science of sex]. Therefore, the concept of treatment in “sexology” and “erotic art” differs. In the former, the aim is to treat physiological dysfunctions for the purpose of reproduction; in the latter, the purpose is to increase pleasure.

These miniatures cannot be separated from the text for which they were created. They are not stand-alone paintings, but part of the text. It’s as if they were both a visual translation and summary of the text itself; they act as a compass that guides imagination in a certain direction. At the same time, they stimulate it, in case the text was not sufficient for us to imagine the characters, events, and places the text depicts. It seems that writers and painters did not see a duality between text and drawing. Thus, miniatures cannot be studied in isolation from the text in which they appeared.

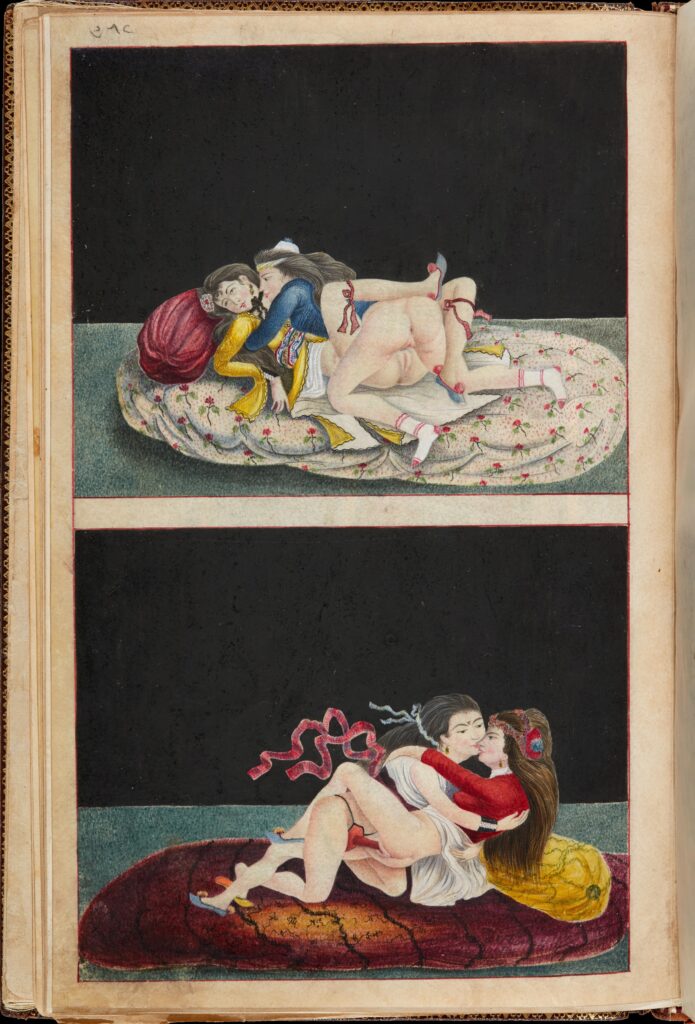

In the next miniature (Figure 5), we see a line of naked men with penises of different sizes and shapes competing over who has the biggest one. This was a central concern that there is an entire chapter in Ruju’ al-Shaykh on herbal recipes for enlarging the penis. And in The Perfumed Garden, Nafzawi explains in “Prescriptions for Increasing the Dimensions of Small Penises, and for Making them Splendid,” the necessity of such prescriptions, meaning that the purpose of these prescriptions was increasing pleasure:

Know … (God be good to you!), that this chapter, which treats of the size of the virile member, is of the first importance both for men and women. For the men, because from a good-sized and vigorous penis, there springs the affection and love of women; for the women, because it is by such members their amorous passions are appeased, and the greatest pleasure is procured for them.8

Below the above miniature, there is another one of the legendary Ibn Alghaz (ابن ألغز), who was described in Al-Raghib Al-Isfahani’s (954 – 1108) Muhadarat al-‘Udaba’ wa Muhawarat Ashueara’ wa albuligha’ (Lectures of Writers and Dialogues of Poets and Rhetoricians) as “The man who, when he had an erection and a camel saw him, it rubbed itself against his penis thinking it was a tree wood.”9 Tree trunks were installed for scabby camels to rub their bodies against them. Sexual knowledge, therefore, was largely focused on the penis and its size. In such societies, effeminate people were fascinated by huge penises, as al-Tifashi says in Nuzhat al-Albab (The Diversion of the Hearts).

However, there were also voices that mocked this frivolous obsession. Muhadarat al-‘Udaba’ tells the story of “Jaafar bin Yahya Al-Sayrafi, the (poor) man who died without having sex with a single woman because of his huge penis,”10 challenging the relationship between penis size and increased pleasure. In another anecdote, it mentions a Bedouin who, mocking this obsession and bragging, said, “that if the size of a penis were a source of pride, then the mule would be the proudest of all.”11

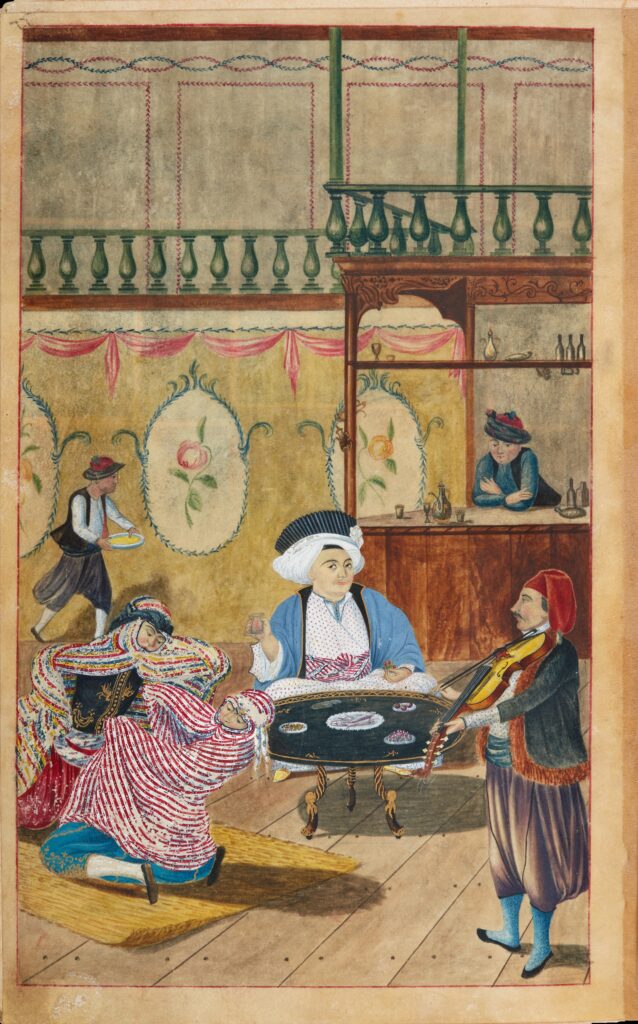

Though most of the knowledge included in this book revolves around penises and penetration, it also mentions lesbianism several times. However, despite lesbianism being common among women, al-Tifashi only made a rare reference to it in Nuzhat al-Albab12 when he wrote, “Talking among themselves about lesbianism, a chief told a lecherous man who asked ‘I wish to know how women practice lesbianism,’ ‘If you wish to know, enter your house slowly on your tiptoes,’”13 hinting that lesbianism was so common that his wife must have practiced it while he was away. Several authors dedicated entire chapters in their books to lesbianism, including Ibn Kemal’s Ruju’ al-Shaykh; Al-Yamani’s Rushid Al-Labib ila Muasharat Al-Habib (A Guide for the Wise on Intimacy); and Muhadarat al-‘Udaba’. However, it is extremely rare to find miniatures that depict lesbianism, making this scripture unique in its depiction of lesbianism in one of its miniatures (Figure 6). It depicts what Arabs called kyrbikh (كيربيخ), a wooden dildo that is worn on the pelvis, which women used to penetrate their female partners. There is an anecdote in Lectures of Writers about a woman who used to wear it to penetrate an effeminate person.

Figure 5: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 184r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 6: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 57v. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Though the author of Ruju’ al-Shaykh asserted more than once that reproduction is the essential purpose of the book, particularly in the introduction:

I did not compile this book with the intention of increasing corruption, committing a sin nor helping pleasure seekers who transgress Allah’s limits. Rather, I compiled it to help the ones whose lust falls short of fulfilling their wishes in halal, which is the reason for populating earth through procreation.14

He doesn’t seem to see anything wrong in reporting anecdotes of sodomy and lesbianism – even though they are not about reproductive sexual practices, and though they are practices he himself rejects – as long as they achieve the goal stated in his introduction: “We mentioned amusing anecdotes and news of female singers that arouse the lust of those who want to have sexual intercourse, increase their appetite and intensify their sexual prowess.”15 He reported sexual anecdotes to serve as treatments like other herbal recipes, writing “Now, I will mention anecdotes, which, if one read them, would stir up his lust and help them fulfill their desire.”16 It seems that the Ottoman translation increased the paintings of these anecdotes by the same principle, that these miniatures represented a therapeutic rather than an artistic significance, arousing the viewer’s lust if needed.

The same logic applies to individual ghilman miniatures that represent the state of perfect beauty. It seems that they were depicted because the painter enjoyed their effeminacy, that he wanted to share the pleasure of gazing at them with his audience and to bring them a state of sexual pleasure that gazing brings. They offer a voyeuristic view into ghilmans’ coquettishness. This has been a central topic in Islamic culture; there have been several debates among fuqahaa (Islamic jurists) about lustful looks aimed at ghilman, which continue today on fatwa websites.

Ibn Kemal acknowledges that these anecdotes and their pictorial depictions, even the sodomist and lesbian ones, serve a therapeutic purpose for anyone complaining about frigidity and lack of pleasure. This contradicts the useless hocus-pocus “treatments” stemming from “sexology” that our societies and authorities prescribe to combat sodomy and lesbianism.17 These paintings are not mere miniatures; they, and the anecdotes associated with them, have a therapeutic nature that is not much different from the herbal recipes prescribed by Muslim physicians.

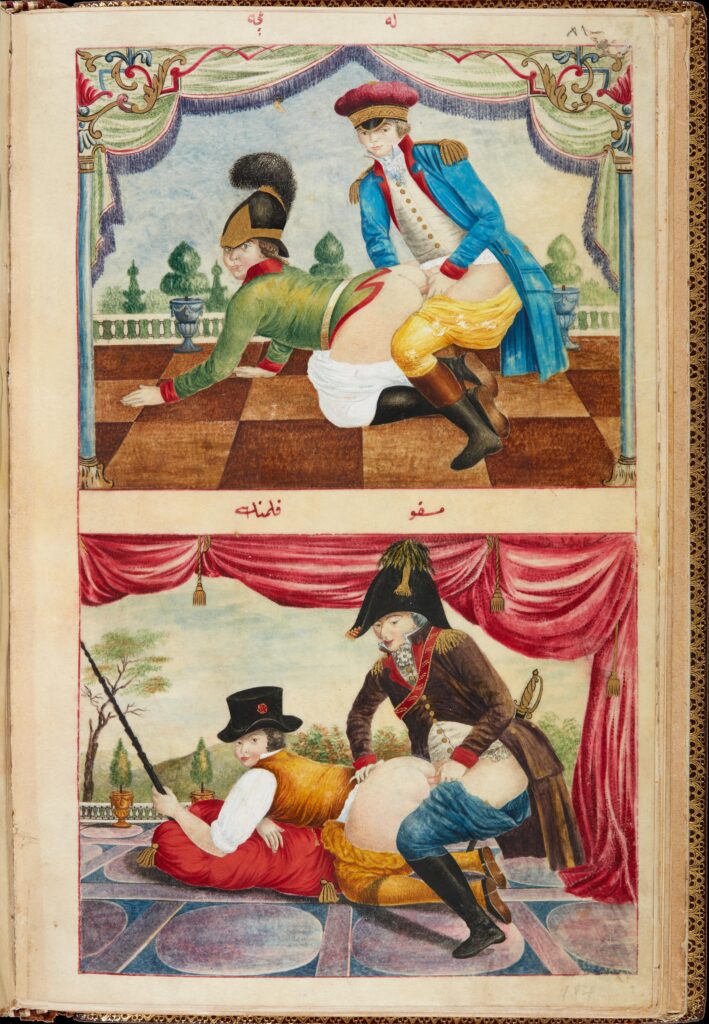

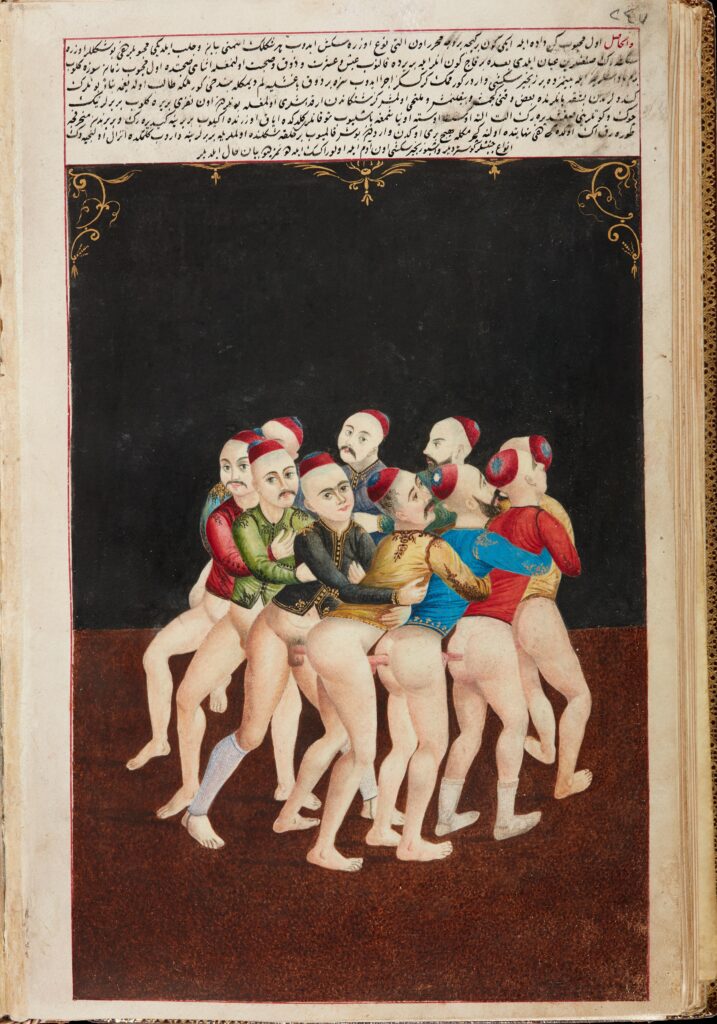

In addition to the various sex positions that Sheikh Al-Masry painted – including missionary style to guarantee pregnancy (Figure 7) and doggie style depictions of sodomy among men from different countries (Figure 8) – we see a miniature of ten men moving in a full circle, fucking each other, each sticking his penis in the one before him (Figure 9). According to The David Collection’s website, this miniature represents the anecdote’s protagonist’s meeting with a young man in the garden, when he begins to explain the joys of having sex with men in sixteen different positions.18 Considering that each position has its own pleasure, the purpose of these anecdotes is to expand the horizons of sex practiced by the readers and the pleasure they reach and to teach new positions. This could add enthusiasm to the individual’s sexual practices, which may have been plagued with boredom after long periods of repetition. After the protagonist explains all these positions in detail, he introduces him to eight friends. Then, they engage in this group sex, forming a full circle where they are all givers and receivers as if representing the state of learning all possible positions. Here, sex roles that generally appear clearly in sexual texts and miniatures are absent, representing an image that casts lust into the heart of whoever sees it.

This, however, doesn’t mean that things were perfect in the past nor there was no hatred, violence, or discrimination. On the contrary, historical texts document these things. And yet, it seems that this hatred and discrimination were not systematic or sufficient to prevent these visual works and sexual heritage from circulating publicly or challenging conservative and extremist views at the time. But the West’s lack of understanding of the difference between their art and our drawings, between their sexology and our “ars erotica,” and their attempts to look at and depict sex in the colonies according to Western ethics and concepts have prevented them from understanding these manuscripts and their miniatures in their own context.

Figure 7: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 10r. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 8: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 41v. Photo: Pernille Klemp

Figure 9: The David Collection manuscript, 1799, 32.2 x 20.5 cm, inventory no. 8/2018, 126v. Photo: Pernille Klemp

- This was confirmed by Sotheby’s when it as auctioned on their website in 2018, e-catalogue, when The David Collection museum bought the manuscript. The title of the book inspired the title of our book, The Return of the Colonizer to Youth.

- George Sarton, and Jamal Juma attribute the book to the metallurgist, astronomer, sociologist, poet and judge Shihab al-Din Aḥmad Al-Tifachi (1184–1253).

- Ruju’ al-Shaykh ila Sibah fi al-Quwwah ‘ala al-Bah, general supervision by Magdy Shoukry, Ibda3 for Translation, Publishing and Distribution, 2008, p. 8.

- The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight, Umar ibn Muhammad Nafzawi, tr. Richard Burton, 1964. P.

- Imagined Masculinities, eds. Mai Ghoussoub and Emma Sinclair-Webb. Beirut, Saqi Books, 2002, p. 245.

- The Perfumed Garden, Nafzawi, tr. Richard Burton, 1964. p. 7.

- The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction, Michel Foucault, tr. Robert Hurley. New York: Random House, 1978, p. 57.

- The Perfumed Garden, Nafzawi, tr. Richard Burton. New York: Castle Books, 1964. p. 117.

- Lectures of Writers and Dialogues of Poets and Rhetoricians, Al-Raghib Al-Isfahani, edited & footnoted by Sajia Al Jubaili. Beirut: Dar al Kotob al Ilmiyah, 2009, v. 3, p. 304.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 305.

- Nuzhat al-Albab, authenticated by Jamal Jumaa for Elrayyes Books in 1992, depends on three manuscripts (nos. Arabe 5943 & Arabe 3055, which are in the possession of Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF). It’s no coincidence that the BnF has these manuscripts; rather, it’s a systemic approach of appropriating the sexual heritage of the colonies.

- Nuzhat al-Albab, al-Tifashi, authenticated by Jamal Jumaa. London: Elrayyes Books, 1992, p. 241.

- Ruju’ al-Shaykh ila Sibah, Ibn Kemal, p. 8.

- Ibid, p. 10.

- Ibid, p. 399.

- Ruju’ al-Shaykh ila Sibah has a recipe for the heartening of lesbianism, and lacks any mentions of discouragement. This means that there was no need or wish to prevent lesbianism, or even sodomy, systemically for medical reasons, though it includes trials to treat hermaphroditism, like the ones included at the end of Nuzhat al-Albab.

- My copy of Ruju’ al-Shaykh includes all of the sixteen penetration positions, but with women. It doesn’t include the ten-men circle. Maybe it was falsified upon publication or it may be that the Ottoman translator added that story during translation.