Words by Nada Majdoub

Artworks by Sarah Bahbah

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

Creating art that engages with themes of intimacy is an act of sharing. It both enables a transformation of internal intimate discourse into an externalized object of thought; and uses this object of thought as a basis for connecting to other people and for threading a collective experience. Ultimately, the healing capacity of sharing encompasses one’s own being and the ones it’s shared with.

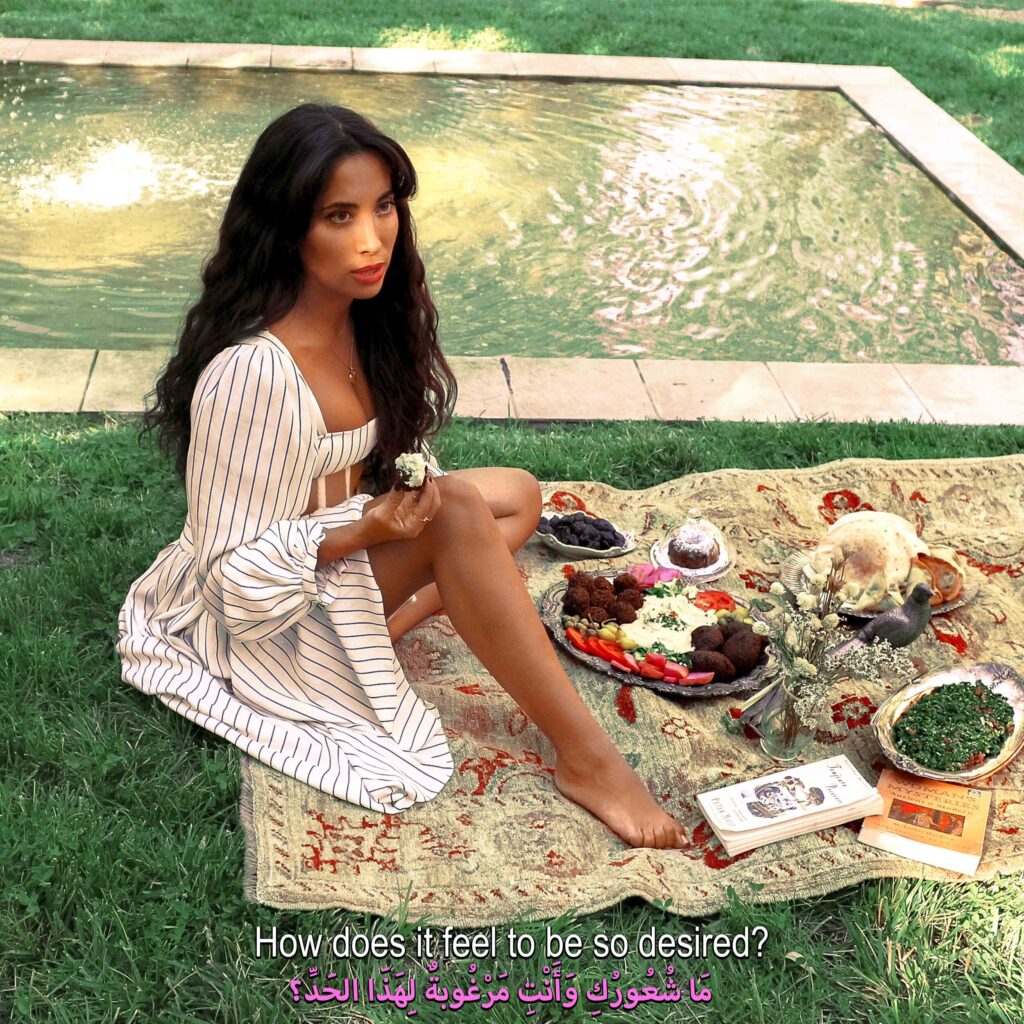

The healing dimension of sharing intimacy is particularly relevant in the work of Jordanian-Palestinian artist, Sarah Bahbah. Conveyed in photographic and film pieces that are shared widely across social media, the images she produces convey the deepest emotional tumult and the artist’s own withheld desires to create a powerful bond between herself and her community. She creates a space for subtle affective and aesthetic identification.

Born and raised in Australia in a Palestinian family that upheld a certain conservative education, Bahbah was confronted with the challenges of performing one’s truthful self at an early age amidst cultural paradoxes and inadequacies. She quickly turned to art as a medium to channel her inner self to the public, most notably on Instagram. Sarah Bahbah’s retro-saturated images, often adorned with witty subtitles and depicting imperfect romances and lustful mise-en-scène, became her trademark and sealed her characteristic style into recognition. Sarah Bahbah walks us through her artistic journey, which is inextricably entangled with her personal one, from her upbringing to the tumultuous passing from her twenties into her thirties. The launch of her first art book, Dear Love, is an occasion to revisit foregone places of trauma and art as a means of survival. This journey, fraught with pitfalls but also with tenderness and love, finally brings her to a more serene standpoint, where a maturing artistic practice and a coming-of-age publication are shaping Bahbah’s new trajectory as an artist and as a woman.

Artwork by Sarah Bahbah

You are a multidisciplinary artist who navigates between multiple identities and reference points. Can you tell us first a bit about yourself? Where do you come from? And where do you live now?

I was born in Australia. My parents immigrated to Australia in the 80s from Jordan, but both my parents are from Palestine, and my mother’s half-Jordanian. I moved to Los Angeles in 2016 and I was quite bicoastal for a few years, moving between LA and New York before I decided to permanently commit to LA.

How do your Palestinian and Arab identities influence your work? Are these filtered through your upbringing in Australia and work in the United States?

Yeah, I actually think the core of my work stems from my identity as an Arab woman. I grew up in a very conservative, strict household with very traditional Arab parents who surveilled me and tried to get me to stick to tradition versus, you know, being influenced by the Western world. But because we grew up in Australia, I was conflicted by my identity. At school and around my peers, things were very Western, and then at home, I was raised within a context of tradition and cultural restrictions. I didn’t really find a place where I belonged.

My art over the past decade is ultimately about me trying to create my own world where I can be both Western and Arab. This narrative is so prominent because it parallels my journey of finding my voice away from my family, whilst also trying to maintain my identity and what I love about being Arab.

Your artistic production includes photography, video, and more recently publishing. It seems that you are comfortable with any medium as long as it allows you to express yourself in a genuine way. Can you tell us about your artistic practice? How did it start, and how did it develop?

I started in high school; I used to do drama and paint. From there, I decided that I wanted to take photos instead of paint. Over the years, that developed into a more refined art.

At some point, I realized that it wasn’t necessarily about the medium that I was using; it was about telling my story. And so I’ve constantly tried to challenge myself to use new mediums to express my message. And so it started as painting and acting, transformed into photography, which then transformed into piecing writing and dialogue with my photographs, which then transformed into film. So it’s a constant push to the next thing. I really love to challenge myself to explore new ways of storytelling.

Artwork by Sarah Bahbah

In your work, you tend to create worlds that revolve around themes of desire and intimacy. Can you tell us more about your aesthetic and artistic influences? How do these inform what you create in your own work?

My subtitled series was inspired by screenshots of foreign films with these kinds of subtitles. In the early 2000s, this style was all over Tumblr. Ultimately, what I wanted to do was to challenge the viewer experience by creating stills that looked like they came from film, but they were actually photographs. It was new, at the time, and it also challenged how users understand the Instagram platform.

The dialogue used in the subtitles is an outlet for me to release my intrusive thoughts and to release my obsessive thinking. Writing these one-liners allowed me to create a space for myself to feel and not harbor any resentment by not being able to use my voice.

How do these elements come together when preparing a series, particularly when you need to work with so many people to produce those images and feelings that are often so hard to convey? What is your process like both leading up to and during production?

When I’m in that process of grief, something that helps make me feel more gentle with myself is to lean into the pain by creating a playground inside my mind and allowing a safe space to express myself. I always do this by romanticizing my exterior and trying to make it feel beautiful even though the protagonist is suffering, even though I’m suffering. You know, if you’re going to be sad, you might as well be sad in a beautiful hotel room, with full service and a bottle of cold champagne. It just makes the experience better and more tolerable on the palate. That’s what I try and depict in my art: I try to create this playground that didn’t necessarily exist for me, but it existed in my mind and helps me get through the situation.

I envision the whole thing before the shoot, and I direct everything during the shoot: every decision, every prop, everything you see, every color, every wardrobe. I’m very particular and, when I work with my team, I work with the best creators out there in my art department. I try to have everything fully fleshed out before hiring the crew so I can tell them what I’m looking for, and then we kind of just discuss the concept and any options. It kind of goes from there.

The models also play an important part in bringing these scenes to life, as the focal point and actor. How do you choose who fits in a particular series, or what might work best?

When it comes to choosing models to work with, it’s never over-thought or too planned. It’s improvised. Sometimes they reach out to me, or I remember them, or I find them on Instagram and am like, who is that really cool person that I saw and wanted to work with, and I take a mental note. When it comes time to present a series, I see who fits the story I’m trying to tell and who’s available.

In the 3eib! series, you feature yourself, bridging the gap between being behind the camera and in its frame. Can you say more about how much of yourself and your experience with intimacy you bring into your work? Do you try to maintain a boundary between your personal and professional understandings of intimacy, or do these domains blend together?

I think, for me, my art is such a sacred part of my self-expression. When I create a series, it usually stems from real grief and pain and suffering. So, when I give my art to the world, I feel like I’m giving a huge part of my essence and my being. That’s also why I’m very careful with who I invite into my space: it requires a lot of trust, knowing that I am giving so much of myself to the world.

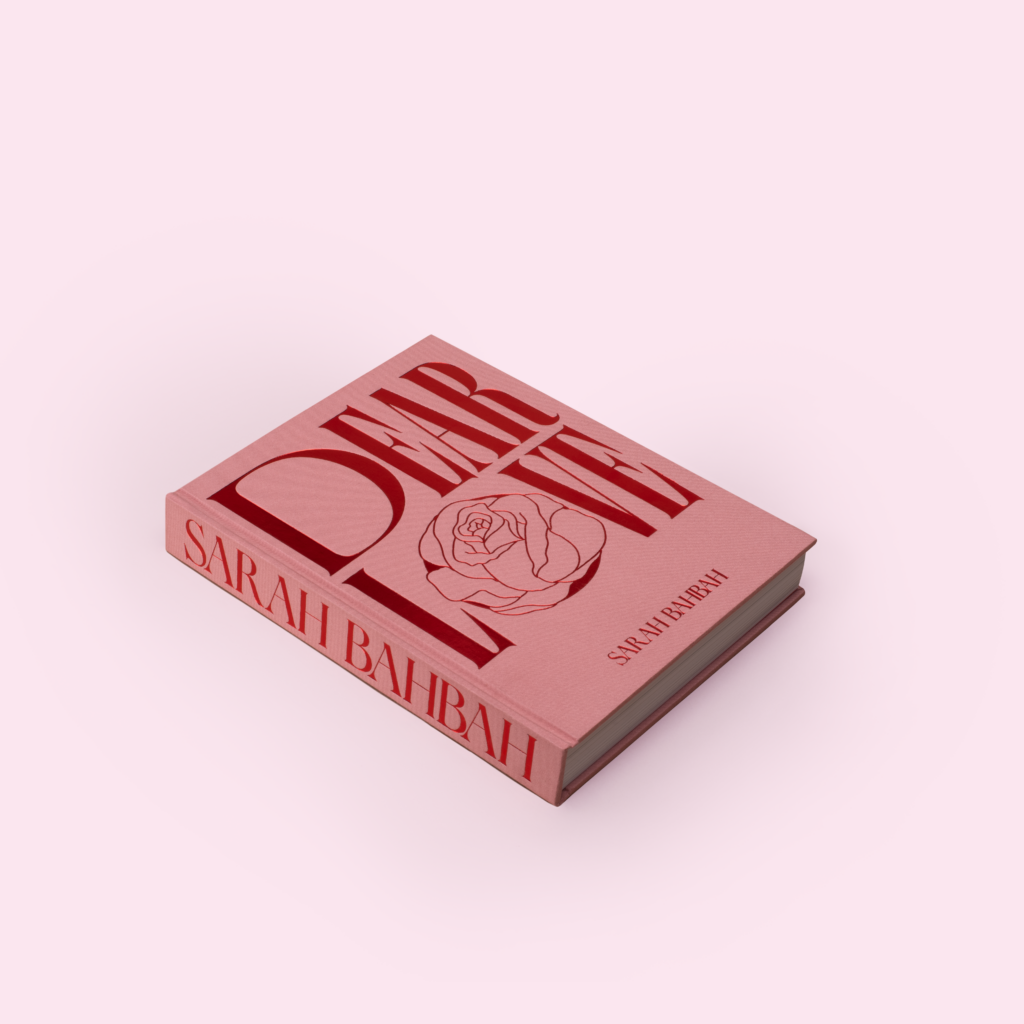

That being said, it wasn’t until my book project [Dear Love (2022)] that I finally dived deeper into what each series actually represents, how each speaks to the depths of my trauma, my heartbreaks, and my experiences at different moments of my life. In this book, I wrote a synopsis for every series, and each is in-depth and revealing. I’ve never done this before, never given a backstory as to who I was talking about or why I was creating the series.

As you mentioned earlier, Instagram is one of the main platforms where you exhibit your work, and many people first encounter your work there. How has your relationship with the platform and social media, more generally, changed over time? What sort of space does social media provide for you personally and for your artistic practice?

I think my relationship with Instagram has evolved significantly over the years. I’ve always tried to ground myself in the fact that Instagram is a tool to release my work and not get too consumed in it otherwise. I used to create only one art series per year. I wanted to develop a practice of creating high-quality art that would take a year to produce and a year to create, rather than getting consumed in creating more content. Instagram was a tool to release it and to just observe.

Over the years, the algorithm has changed and things like Reels and TikToks have become more prominent than static images. It’s kind of, unfortunately, forcing artists to change how they use the platform. If they want to be seen and have that presence online, they have to continuously post content. Right now, I’m trying to navigate and figure out how to stay present and active online without creating shit just for the sake of it. I don’t want to just create content, I want to create art and I want to stick to that. I’m currently struggling with how to do both without giving up a part of myself.

Yes, it’s an interesting balance that artists are forced to make, particularly when so much of their success relies on being visible online. Does this level of exposure on social media impact your private life in any way?

I don’t share a lot of my private life on Instagram. I look at it like I’m curating based on themes. I will share images of me and my partner on a vacation, but I’ll never reveal who my partner is, and I’ll never reveal where I am until later. If I don’t stay present in the moment or in my personal life, I’d get so consumed with trying to prove something to my viewers or just overshare. I’d never have a very grounded life if I lived like that. It’s really important for me to separate the digital world from real life, so what I try to do is give glimpses of my life without telling the whole story.

Artwork by Sarah Bahbah

A lot of your work conveys dynamics of love, sex, and fantasy, but also pain. What has your artistic practice taught you over the course of your career regarding these topics that you would like to share with us?

If anything, it’s made me feel a little bit crazy and unstable. [She starts laughing]. For the longest time, it was almost like I was subconsciously leaning into heartbreak and pain to keep creating art. I didn’t really recognize that I was doing it and that I was intentionally self-sabotaging because the pain and the chaos felt so familiar. So, I kept dating the same kind of people and leaning into bad habits, and I would almost intentionally get my heart broken. As someone who has struggled with dissociation and apathy for a long time, when you get a wave of feelings – whether it’s depression or euphoria – and find a way to access it, you don’t want it to end. As an artist and someone who doesn’t get the luxury of feeling like most people, I would subconsciously try more ways to feel. That runs through all my art.

Can you tell us more about your book, Dear Love, which launched this year? It’s an autobiographical and artistic publication that shows the life of Sarah unfolding over the course of 10 years. How did the project come about and what makes it so special for you?

As you said, it’s a decade of art, it’s all of my 20s in one place. I wanted to create this book to celebrate the life that I’ve lived so far, and the things that I have overcome. I wanted to give people the tools and the backstory as to how I got to where I am now. Who I was in my early 20s and who I am in my early 30s are completely different. I survived a lot, and I was alone for a really long time. What this book does is take the readers and the viewers on a journey of self-discovery. I ultimately speak to how I use my art to navigate my trauma and my pain, and I think that sharing how I did this will potentially give others the tools to do this for themselves.

Do you want to tell us more about your upcoming projects and maybe things that you are excited about? What would you like to do in the near future?

Well, Dear Love is the biggest project right now that I’m most excited about. I spent a whole year working on it. It was 12 to 16 hours a day, every single day, for the entire year. I’m really excited for everyone to experience it and hold it in their hands and learn new perspectives about my art and how each series that they both shared and loved came to be.

Sarah’s Book, Dear Love, is officially available to purchase as of Valentine’s Day, 2023 https://dear-love-book.com/