Words by Hamza Bensouda

Images from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

A step backwards: From postcards to Orientalism

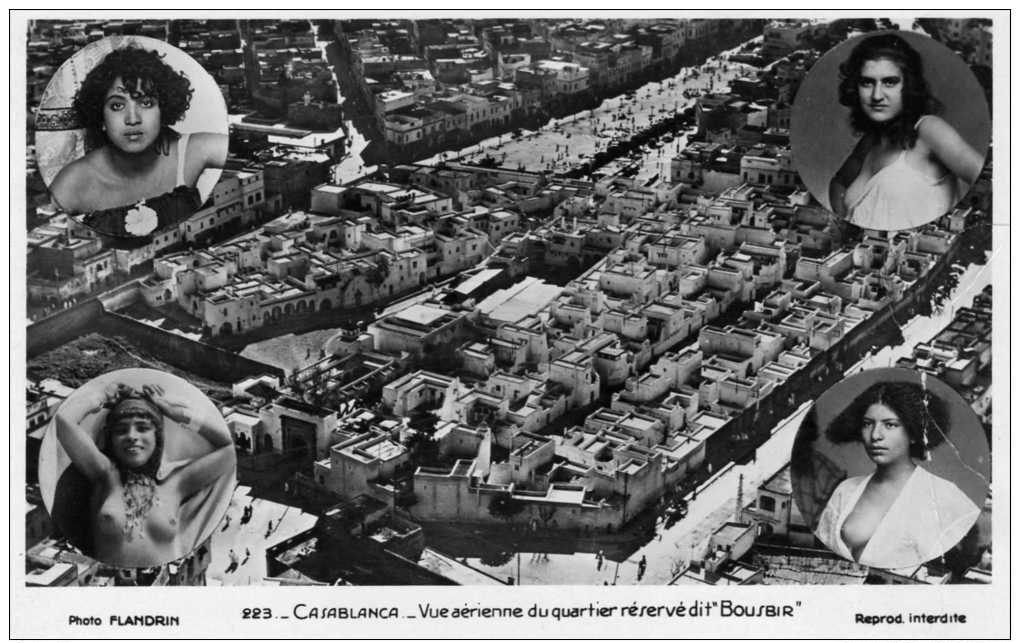

For the French colonists who entered the Bousbir district in Morocco during the protectorate (1912-1956), who got lost in the busy streets of Algiers occupied between 1830 and 1962 or who pined before the vision of the blue ocean joining the sky in the port of Tunis during the Tunisian protectorate (1881-1956), the Maghreb was as much a colorful source of wonder as a space to civilize. This language was configured and mastered in a seemingly unified visual language of paintings produced by eminent artists, adorned with illusions and decorated with the style of Orientalism, and daguerreotypes of travelers to these countries. The circulation of these colonial works of art and image to those afar contributed to the eroticization of the Maghreb, the justification of the French colonial enterprise, and the lightning of tourism in the occupied territories in the direction of the French of the metropolis.

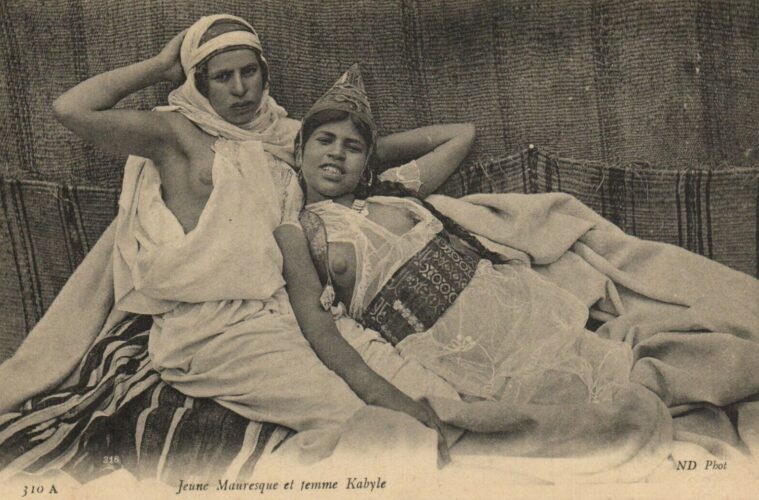

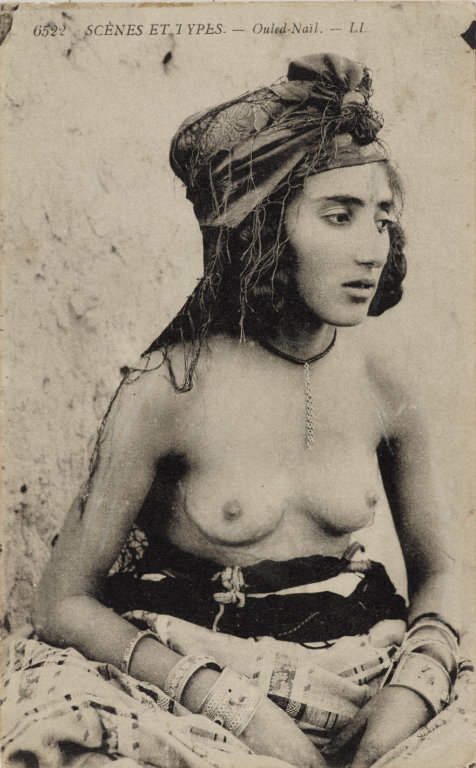

Postcards stand out among these forms of photographs and visual representations. They were used widely to share testimonies of experiences of settlers from the other side of the Mediterranean: declarations of love, like that of a stranger to his lover “I think of you,” and daily anecdotes, like that of Marius to his friend “Always an atrocious heat and an overflowing work” or wishing his brother a “good year and good health.” But on their reverse side, one would realize the disturbance of their subject: there’d be surprise in finding bare-breasted women – sometimes alone and sometimes in groups, sometimes with piercings or decorated with jewels – outstretched, indolent, exposed before the eyes of the viewer

These images, which reveal the gross power imbalances and objectification of colonialism, have become a focal point in postcolonial studies. They tell us not only of the colonial project but also the truth of Orientalism to present.

Distributed throughout the protectorate and back to the metropole, these sexualized representations supported the colonial construction of the Maghrebi women as Arab women – a simplistic generalization. After having carefully unveiling the Kabyle, the bodies of Moroccan and Tunisian women were offered back to the metropole, elaborating an image of Maghrebi women as dangerous, lustful, sexual women to be easily taken by colonial powers and governments. These images endure in Western imaginaries and constructions of the Orient today, though it is now the unattainable women behind her veil who is offered to the western world. The beurette, a pejorative term, the feminine of “beur,” deriving from the inversion of the word “Arab.” Whether in the orientalist paintings of Benjamin Constant in the 19th century or in contemporary searches on pornography1 sites, the idea is the same: the Maghrebi woman is an object of fantasy, a femme fatale, sometimes a witch, sometimes a prostitute, and always easily accessible.

Image from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives

Several have written on the effect of representations like those on colonial postcards on the construction of the image of this “easy Maghrebi woman” in France and the West, including Marnia Lazreg in The Eloquence of Silence (Cambridge, 1994) and Salima Tenfiche and Sarah Diffalah in Beurettes: Un fantasme français (Editions Le Seuil, 2021). However, little attention has been given to the effect of this diffusion of colonialist artifacts, ideas, and stereotypes in the non-European world and, especially, in the SWANA region. Not only are the resulting stereotypes just as widespread as in the West, but they sometimes support legal arguments restricting Arab and Maghrebi women’s rights and mobility.

In the Arab world, Maghrebian sexualization is alive and well

There are many examples where the figure of the Moroccan woman is closely linked to pleasure. The Saudi Series, Chir Chat (2018), shows a Moroccan woman who is “easy to buy,” the target of clients wishing for a night out or “pleasure wedding.” In Dubai, the presence of “Moroccan women” has become a selling point for private parties as a guarantee for pleasure. Similarly, the label of “Moroccan women ” has been taken by some women, for example by Syrian or Lebanese sex workers in Amman. A Jordanian sex worker confided that “the Moroccan label sells well” in the Arab world.

As in the case of colonialism, we no longer speak of Moroccan women but of the Moroccan woman, an essentialist reduction that pleases those who enjoy it and that benefits the sexual capitalism that plagues the region. Moreover, it is the same for the Tunisian woman in the Gulf where she represents “a more accessible woman than a Lebanese too tempered,” as an organizer of a private party in Dubai said it. Thus, women are apprehended like objects of desire and are gradually transformed into capitalist objects to be consumed. Their physique, size, and origins become objects of commentary and fantasies. And like any other object, they are described according to a series of categories putting them in competition and praising the merits of one more than the other, a misogynistic and repulsive colonialist process that is accentuated as other nationalities appear in the Gulf countries.

Image from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives

This image portrayed is not limited to symbolic violence, a gateway to physical violence; its influence is also seen in the laws governing whether Maghrebi women can enter particular territories. In 2019, Mounia Semlali, Moroccan head of the gender justice division of the organization OXFAM, was refused entry to Jordan. At the end of 2021, a Moroccan student, Camelia, was denied boarding to the same country. In both cases, the Travel Information Manual listing the conditions of entry into the country displays a box as specific as it is out of the ordinary: women – precisely Moroccan – between the ages of 16 and 36 need the agreement of the Ministry of Interior or must present themselves with a mahram, a male family member representing her.

The effects of these images are also evident in the ways that people administering these laws objectify Maghrebi women. Testimonies of several Maghrebi women reveal patterns of experiences. One young Moroccan woman recounts being told that the reason she was refused entry to Jordan was “because you Moroccan women have come to prostitute yourselves and upset traditions.” Another Tunisian woman reported being the target of sexist remarks by customs officers in Egypt, “You Tunisian women are sweet.”

Thus, we see that Orientalist, sexist, and sexualizing clichés have moved through the region serving as a basis for discrimination of Maghrebi women whose bodies are as much sexualized in the West as the East and for their infantilization. Forged by colonial legacies and diffused through cultural artifacts and imagery, these dynamics continue to unfold today. However, it is not only Europe or other areas of the SWANA region or sexual capitalism that bears the responsibility for these dynamics; the Maghreb governments also play a role.

Image from the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives

In the Maghreb, colonial legacies still taboo and censored

Called the Disneyland of sex in Morocco, the Bousbir district of Casablanca has long served as a haven for prostitution. It was constructed to satisfy the sexuality of the colonists and was a place where Moroccan women were delivered and encouraged into prostitution. Many colonial postcards that can be found today proudly display this neighborhood. This led two researchers from the University of Geneva to set up an exhibition in Casablanca (2022-2023) to discuss the figure of women during colonialism. However, it was canceled the day before the scheduled opening and the book associated with the exhibition was banned from distribution. No rational was provided. The denial of such discussions is not unique to Moroccan society or government. In Algeria, most postcards have been burned without any discussion of the colonial legacy it represents. Marnia Lazreg noted that, while research on Algerian women during French occupation is “still a vast fertile field,” it is rarely investigated.

The question of the protection of women’s bodies in the Maghreb and their stereotypical representations does come up, but it is so closely linked to colonialism that the Maghreb governments tend to avoid it. Worse still, in the case of visa refusals based on sexist arguments, as in the case of Camelia, diplomatic issues seem to supersede the dignity of the body. No official response has been given despite numerous media statements. If this objectification and sexualization have deep roots in colonial diffusion, its future is ensured by the lack of responses from Maghrebi governments, in which questions of sexuality are often subject to taboos and conversations avoided.

The societal responses to the #metoo movement in Tunisia (#enazeda), the heated controversies around Moroccan films about sexuality (such as Nabil Ayouch), and Algerian censorship around debates about sexuality seem to be added obstacles to discussions about legacies of colonial representations of women. But this censorship can be based on conservative societies sometimes playing the role of censor and interpreting feminist (and queer) debates around these issues as dangers to social peace and completely imported into the country. However, history remembers who sexualized whom…