Words by: Sarah Kaddoura

Translations by Hiba Moustafa

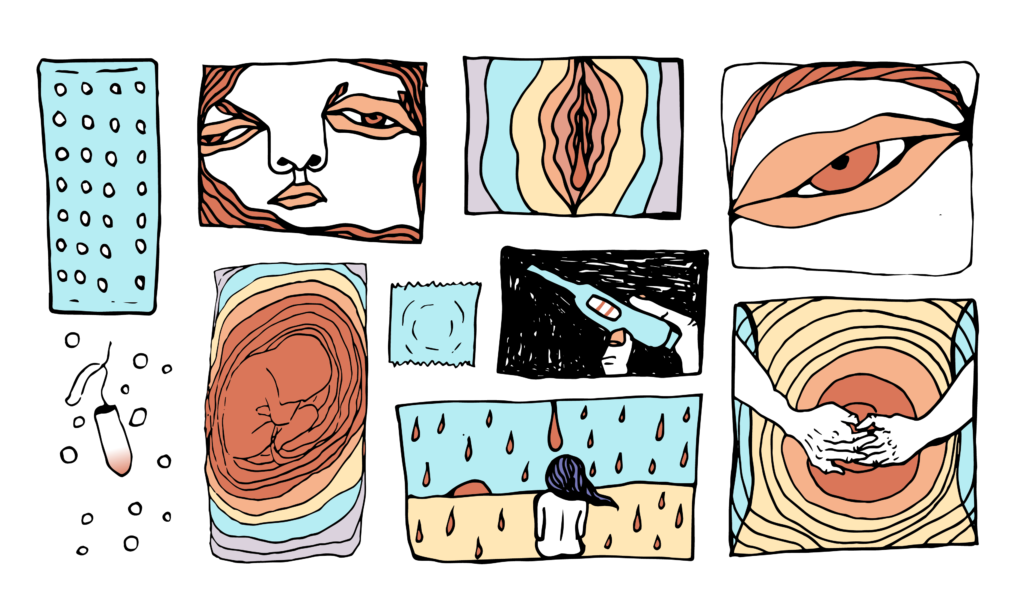

Illustrations by: Qaduda

In the early 1960s, the universal use of the combined oral contraceptive pill (or simply “the pill”) in the Global North contributed to what we call a sexual revolution today; for the first time, not having children became an option for cisgender women. Exactly two decades later, HIV spread basically among men who had sex with other men, and the US government’s neglect towards medical research led to high AIDS-related death rates. In the former case, contraception, despite its potentially dangerous side effects, was a tool for liberation for many women who were at the mercy of their reproductive role. In the latter, the lack of sexual healthcare exacerbated the prevailing ideas that linked sexual pleasure, already demonized, with disease and death.

Sexual and reproductive rights are defined as a set of factors, services, and beliefs that guarantees people’s health and psychological well-being regarding their sexual and reproductive (and non-reproductive) choices. This set includes important conditions that focus on consent and mutual understanding in relationships, the right to access health services, and the right to lead a dignified life regardless of our orientations and sexual lives. Though this set of rights dominates how we conceive sexual and reproductive health, several countermovements have emerged, critiquing its focus on the rights aspect and suggesting to resort to concepts such as justice.

The Reproductive Justice Movement, made up of Afro-American individuals and groups, sought to place conversations about sexual and reproductive rights within their social, political, and economic contexts, for these contextual factors influence our access to rights in the first place. For example, everyone is entitled to reproductive healthcare, but being an unmarried woman in a country where physicians request to see a woman’s marriage certificate before they give her a cervical screening 1 denies you this right. Though sexual health is an essential component of general health, one could be easily denied a medical consultation if they were a trans woman with a “male” marker in their ID. And understandings of what constitutes sexual health and rights rarely include sexual pleasure, for these understandings are influenced by our personal and inherited beliefs, and by the circumstances in which we have sexual relationships.

This article examines the relation between sexual pleasure and our access to sexual and reproductive health and rights in the Arabic-speaking region in the light of a cultural heritage that sees “good sex” as something that happens between heterosexual spouses and only through specific practices that do not violate public morality. Before writing this piece, I distributed a survey to collect the experiences of individuals from around the region, which asked about their personal experiences as well as the information they received about sexual and reproductive health, their beliefs growing up, and the health services that were available to them. 74 people between ages 17 and 41, from 11 Arabic-speaking countries, who identified themselves along a diverse spectrum of sexual orientations and gender identities, completed the survey.

Do I Have the Right To Have Sex?

“Good sex,” as defined by queer theorist Gayle Rubin, is the one that falls within moral standards set by society, where everything that doesn’t conform to these standards is met with disapproval, stigmatization, ostracism, and punishment. “Good sex” differs from country to country and even within the same country. It is influenced by one’s social class, nationality, ethnicity, and other affiliations that have broad definitions of what is acceptable as “proper sex.” In a Muslim neighborhood in Cairo, for example, “good sex” is the one that occurs between heterosexual, married couples behind closed doors and results in pregnancy, children, and family. Meanwhile, in Mar Mikhael in Beirut, “good sex” may be the one that occurs between a heterosexual dating couple or between two young men in a monogamous, romantic relationship; upon leaving the neighborhood, the two scenarios become unfavorable. The farther we move from the concept of “good sex” in one place or another, the more the fears and risks around sex grow.

We hear about, and sometimes witness, honor killings (جرائم الشرف) related to the idea of “good sex” in our region. However, though “good sex” is still based on the ideals and stereotypes of heterosexual marital relationships, a high percentage of the respondents to the survey said that they felt a little pressured to have sex for the first time. This doesn’t necessarily mean they were coerced or deceived into doing it, as is the case for some. Rather, they could face direct and indirect pressure to have sex before they were ready, perhaps by colleagues or acquaintances in certain circles, particularly the ones deemed to be progressive, feminist, and/or queer. One respondent mentioned that she felt excluded from sex-related jokes and talks because she was a “virgin” and another said that she felt she wasn’t really “positive” about sex if she hadn’t done it yet.

it is obvious that knowledge alone is not enough to “empower.” Fear and panic remained evident in the responses that asserted the respondents’ excellent knowledge of STIs, since such knowledge is smeared with stigma and exists alongside a lack of responsive health services.

Vaginismus 2 was common among many of the respondents who were assigned females at birth. Usually, those who suffer from vaginismus are referred to psychotherapists to help them get rid of cultural “residues” and accept that it’s their right to have “bad sex” (though this even happens to women after their marriage). Sexual health specialist Dr. Caroline Osman echoed this in Netflix’s docu-series, Sex and Love Around the World, in the Beirut episode, which largely played on stereotypes of sex and taboos in Lebanon. But, what such analyses overlook is that fear doesn’t always stem from deep-rooted beliefs or violent surroundings, but may be influenced by the lack of treatment options for any unwanted sex outcomes. Decades after inventing the pill, many countries still restrict unmarried women from accessing it. In the UAE, for example, the emergency contraceptive pill (sometimes known as the “morning-after pill”) doesn’t exist 3. In Jordan, it may be easier to order abortion pills online than to find a physician who would agree to give you a prescription or help you get a surgical abortion. In Lebanon, though some STI examinations are available for unmarried women and queer people with less stigmatization, the cost is very high and not everyone can get them regularly as recommended. Even in some European countries and American states, you cannot get contraceptives without a prescription. And, even when physicians know “virginity tests” are a socio-medical hoax, and that the women who resort to seeking “hymen reconstruction” are often in danger, they still request high fees for the simple, yet “deceptive” procedure.

People may overcome the beliefs that they grew up with that link sex with honor, and they may have a considerate and understanding partner who doesn’t pressure them. But, still, knowing that they might find themselves trapped if they got pregnant or contracted some infection could be enough to make them nervous every time they have penetrative sex.

Regardless of whether we have a vagina or have suffered from vaginismus, fears related to lack of access to services go beyond what we want to “treat.”Sexual threats and blackmail were common among the respondents. Family or social norms are not the only concern when we have sex; our bodies and sexual activities may be revealed to society. Sexual blackmail is not exclusive to our region, but the difference is that we are not “supposed to” be having sex in the first place. Some respondents said that they didn’t feel comfortable having sex until they left the places and countries they grew up in, for even if their photos were never leaked without their permission, they would trust neither healthcare providers nor laws that pay not much heed to blackmail or sexual assault.

Illustrations by: Qaduda

What Kind of Sex Am I Having?

Sex as we know it is based on heteronormativity, and attraction is supposed to be between a shy female and an assertive male who wants to satisfy his desires. Some cis-women respondents said that they were not certain about their sexuality. One of them said, “I’m straight because of my surroundings; I don’t know what I’d have been if I had grown up somewhere else.” The prevailing expectation that it is “normal” to be attracted to the “opposite” sex influences the kinds of desires and practices that we are comfortable exploring.

Even when we receive sexual knowledge from non-traditional platforms (for example on the internet, social media, or TV), the main focus remains on heterosexual relationships. For example, Hakeh Sareeh ( حكي صريح), a podcast by psychosexologist Dr. Sandrine Atallah, is one such alternative source for sexual knowledge that was mentioned by respondents, and though it’s one of the few platforms that discuss sex “openly,” it has nothing to offer to those of us whose sexual activities do not adhere to heteronormativity regarding our bodies or relationships. Matters are further complicated for trans people who rarely find information about taking hormonal medications, relating to their genitals, and getting to know their bodies after having surgeries. (Note: no single experience represents all trans experiences).

This gap also applies to discourses on the right to sexual pleasure. A common response to the question, “What was the information that helped you get comfortable with yourselves, that you wished you had known before having sex for the first time?”, was that sex doesn’t revolve around men’s desires. Norms about sex, sexual knowledge, and expectations tend to be gendered in heterosexual ways. One woman wrote about her experience with phone sex, saying that she was asked to moan while he talked about what he promised to do to/with her though it didn’t actually arouse her. But, though she loved giving orders during sex, her partner refused to compromise and obey because he thought it emasculating. Despite many cis-women seeking sexual knowledge on sexuality hotlines like the A Project’s hotline (مشروع الألف), so little is expected of women, their knowledge, or their desires during sexual encounters. And, though many people can only orgasm through oral sex, it is often deemed inferior to “real” penetrative sex and neglected.

Knowledge Is Power?

Knowledge empowers. This is usually the argument used to advocate for including sex education in schools. The reasoning is that the more we learn about our choices, the more responsible we are when we make those choices, or at least this is the most socially acceptable argument in most countries to encourage or discourage having more children. The logic has some truth to it, but even those who received some sexual education in school said it was done in a sex-segregated context, and that the content covered was strictly biological and focused on menstruation and reproduction. Though alternative sources and media have the potential to fill this gap, they do not always take our contexts or fears into account, making it difficult for us to navigate information smoothly, find answers to our specific questions, express our concerns or find something that fits our cases.

Today, some alternative initiatives are emerging in our region, including Podcast: Hakeh Sareeh, TheSexTalk Arabic, and The A Project’s sexuality hotline, and are receiving a lot of engagement. The latter two aim to reclaim the knowledge of “experts” into something close to people’s actual experiences, focusing on consent and pleasure with space for non-heteronormative practices. Other initiatives like Transat (ترانسات) provide information while offering a space for trans people to ask questions and share their experiences with medications, hormonal changes, desires, and living in safety. Though these initiatives are important, they do not make up for the fact that we need a comprehensive sexual education program that is accompanied by access to sexual and reproductive health services.

When respondents assessed their knowledge of several topics related to sexual and reproductive health, it was obvious that most of them trusted their information on matters like contraceptives, virginity, menstruation, consent, and self-pleasure (which can be attributed to recent efforts to spread necessary knowledge). In contrast, their information on topics like STIs, post-rape follow-up, abortion, gender-affirming hormones, and non-heteronormative and kinky practices was scarce. Apart from respondents in Tunisia, where abortion is legalized within limits, fear of pregnancy influences cisgender women’s choices according to the survey. Additionally, people do not look for information on gender-affirming hormones and surgeries unless they are personally invested. Also, some of the respondents’ legitimate fear of rape and sexual assault is even further exacerbated when they know very little about post-rape options and practices, such as medical treatment interventions, precaution testing, and psychosocial support when necessary (if these existed at all).

Yet, it is obvious that knowledge alone is not enough to “empower.” Fear and panic remained evident in the responses that asserted the respondents’ excellent knowledge of STIs, since such knowledge is smeared with stigma and exists alongside a lack of responsive health services. Both context and the way information is provided still affect how we use and deal with it. For example, if the majority of sexually transmitted infections awareness campaigns, particularly HIV, still spread panic and mainly target men who have sex with men or transwomen, then the result will be more panic among these people. Most don’t know that all infections can be treated and a fair number of them can be cured completely. They know, however, that the centers that receive unmarried and/or queer people are few, expensive, and full of judgment, too. One of the respondents provided another example when she said, “My fear of pregnancy or STIs stems from my fear of doctors. Lack of care, judgment, and harsh treatment towards women and oppressed groups scare me. Every time I have to ask myself, “Where can I go? Who do I feel comfortable talking to?”

Knowledge is not enough to have a safe and passionate life, for access to services represents the second half of the equation. Comfort, pleasure, and sexual satisfaction are not mere rights that we get to obtain once we know of them, but experiences that require accessibility, privacy, safety, relief from stress, and an assurance that addressing all of the consequences of sex that we are intimidated by is possible.

- Cervical screening is an examination that detects any abnormal changes in cervical cells that might become cervical cancer if not treated appropriately.

- It is a medical condition in which the vaginal muscle walls get so tense when exposed to any kind of penetration (penis, finger, toys, medical equipment, etc) that they close up partially or completely, barring penetration from taking place or ensuring the process is painful.

- It is a type of emergency birth control that is used to prevent pregnancy following unprotected sex.