Interview by Ayyur

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri

Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson

Stylist Assistant: Nawal

Nails by Pablo Esconails

Hair and Makeup by Inès

Set design & backdrops by Pangea

This article is part of the “Ya Leil Ya Eyein” issue

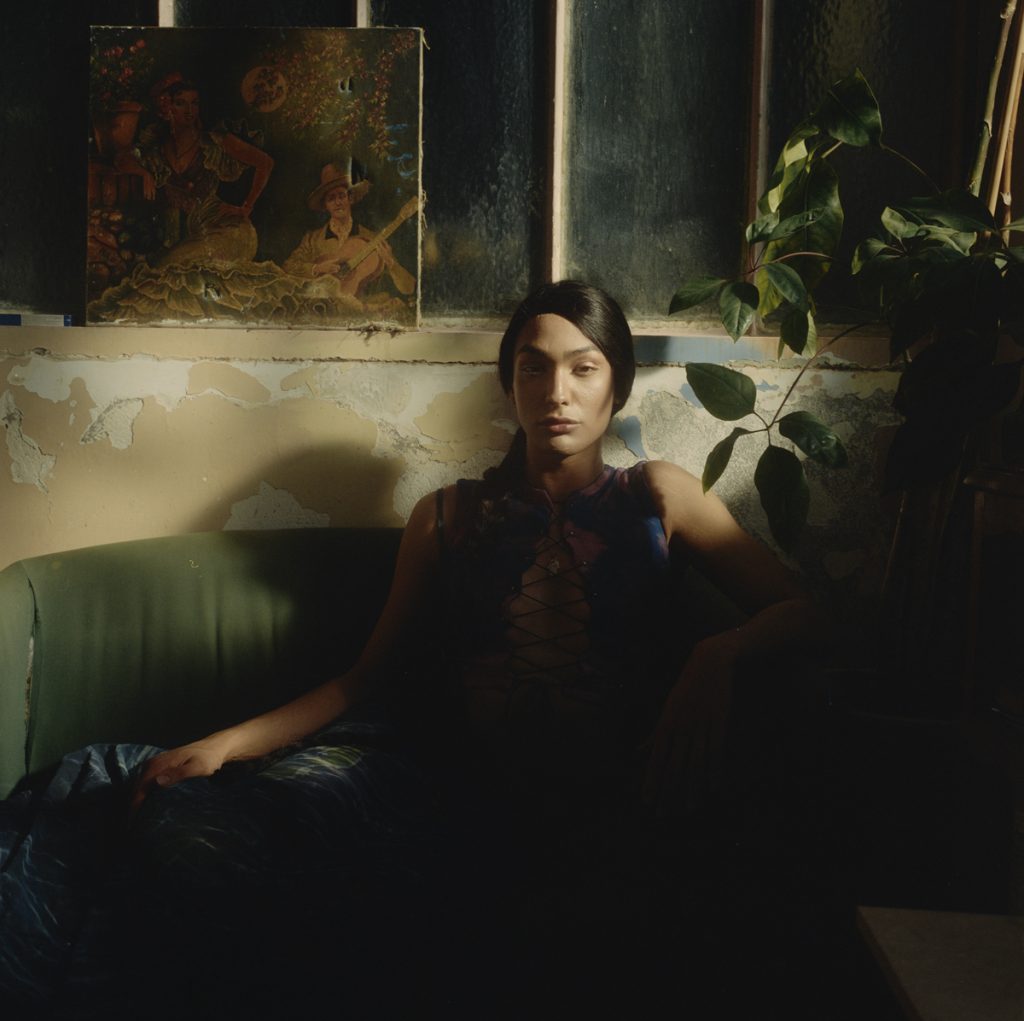

If you get lost in the streets of Paris, you may see this sweet, proud, and radiant woman walking around. A small bag in her hand, a crop top brushing against her waist, hair in the wind, a smile hanging on her lips, Lalla Rami’s commentary and punchlines will both seduce you and give you food for thought.

A goddess of more than 1m80 tall, Lalla Rami grew up in Kenitra, Morocco before beginning her journey here in the City of Lights. As a trans woman who embodies strength, determination, and talent with words, Lalla mixes French, English, and Arabic to craft potent and progressive rap lyrics that blend her position in a masculine universe and her specific path and scars. In her latest single, “Inchallah,” this “rose in the dry desert” dreams of singing in Rabat.

Lalla Rami welcomes us into her space, where music and rap blend and resonate in ways that give us hope as much as shock us to reality.

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri. Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson. Stylist Assistant: Nawal. Nails by Pablo Esconails. Hair and Makeup by Inès. Set design & backdrops by Pangea.

When I discovered your work, the first thing that intrigued me was your name. Does “Lalla Rami” have a particular meaning for you?

I chose this name because “Lalla” is an honorary title dedicated, for example, to the princess that I am. “Rami” refers to the archer in Moroccan Arabic, because I have several arrows in my bow. As simple as that, “Madame l’Archer.”

Lalla Rami was born in Kenitra, Morocco in a house where her parents’ musical tastes clashed. What did your family listen to when you were little?

We listened to a lot of chaabi. My grandmother listened to a lot of Nass El Ghiwane and Oum Kelthoum. My mother loved Toni Braxton and my father the Eagles. And there was my aunt who I was close to and who loved pop music. She’s so queer. She listened to Mariah Carey, Madonna, Janet Jackson, Prince, Queen, and David Bowie. Put all these references in a blender and you get Lalla Rami.

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri. Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson. Stylist Assistant: Nawal. Nails by Pablo Esconails. Hair and Makeup by Inès. Set design & backdrops by Pangea.

And to really finish the recipe, shouldn’t we sprinkle one last ingredient: rap?

Hip hop and rap arrived thanks to my cousins with, for example, “Ladies Night”. I was 12 years old at that time and I already wanted to be a pop star. I told my mother, “yes, I’m going to have to make career choices when I grow up, but I want my impact to be bigger than myself.” I started writing around that time, mostly fiction and later songs in English. They were very bad in terms of English, but the rest could have competed with the ones that were in vogue at the time.

The influence of rap in your musical tastes and in your music has been built throughout a period where we discover and define ourselves: middle and high school. How did this period shape how you lived your music or your identity?

I used to get bullied a lot in middle school. I was very depressed and I used music and comedy to try to get out of it. Music, in particular, was central and represented how I felt – I wrote a lot of songs. Later, during my first two years of high school, I released two mixtapes with titles that were pretty transparent about my mental health state. People stopped trying me when I started to hold my head high and not let anyone step on my self esteem, and I started to be more and more myself. Everything was very linked.

At the end of high school, I had red hair and wore crop-tops and nail polish, but I didn’t go out a lot because I knew it wasn’t safe for “girls like me.” I’m talking about physical appearance – it felt like being in a cage and screaming that I was miles away from how people perceived me through my style. However, I didn’t have the right to exist, and I couldn’t imagine at that time being the woman I am today. It was the limit of my hopes to be Lalla Rami.

Being strong, enduring, and living with this violence at a young age leads many to leave the country. Can you tell us more about the steps in your journey and why you chose to leave Morocco?

I always knew I was a woman as much as others have always wanted to tone down my womanhood, my light because it scared them. I needed to leave because I couldn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. I knew I couldn’t be the woman I am today or get any opportunities whether it was for an everyday job or in the music industry. I got my Visa after getting my baccalauréat and left my home country for France.

At the beginning, I stayed one year in Dunkerque, a city where a lot of people were very openly racist, lgbtphobic and transphobic. I hated it and, paradoxically, I’m glad I got there before Paris because I was able to have a different experience than I would have had if I had come to Paris in the first place.

You went to Paris, the City of Light, from Dunkerque on the advice of a friend. What was your mood when you arrived?

I was thirsty. Now I’m ready to eat.

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri. Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson. Stylist Assistant: Nawal. Nails by Pablo Esconails. Hair and Makeup by Inès. Set design & backdrops by Pangea.

On BrutX, we hear you talking about freedom, writing, and music in Paris. To what extent do you feel safe in the street?

In Paris, street harassment is incredible. I have so many stories and so do my friends.

At one point I lived next to a mosque and men were coming out. A man was coming out of the mosque with the sejada on his shoulder, looked at me and let out a “La hawla wa-la quwwata.” I saw that he entered the same residence as me and I opened the door for him saying “Allah taqqabel A’mi.” When I said that, he gagged – he was shook, destabilized. You could see that he was thinking… “Well, the trans woman that I insulted just asked God to accept my prayers, I’m a piece of shit.”

Whether it’s in these streets or in the music industry, I’m not asking anybody for permission. I’m just myself and if somebody’s got a problem with that they can choke on my Moroccan baguette.

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri. Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson. Stylist Assistant: Nawal. Nails by Pablo Esconails. Hair and Makeup by Inès. Set design & backdrops by Pangea.

Your first EP, Inchallah, is now available, and you played it on the day of its release on the stage of the Bataclan. What does this music mean to you?

I wrote this song at my lowest point. It was pure catharsis – I wrote most of it in like 10 minutes while crying my eyes out, and then I went back and changed and added bars until it felt right. There was nothing intentionally political about it initially – it’s my soul screaming for life. My very existence is extremely political whether I want it to be or not. It’s not a choice, it’s facts.

Performing it at the Bataclan the night of its release was magical – it felt like spreading light, hope and love into something so dark. Since then, it’s been fulfilling to see all of the messages people send about how the song impacted their lives and how much it means to them. It was also heartwarming when, during later performances, people knew the lyrics by heart. I’m not alone anymore, we are all in this together and it’s the best feeling in the world.

Photographed by Giulia Frigieri. Designs and Styling by Leila Nour Johnson. Stylist Assistant: Nawal. Nails by Pablo Esconails. Hair and Makeup by Inès. Set design & backdrops by Pangea.

In Inchallah you claim back your spirituality. You sing “Only to God I give praise.” Why do you need to reaffirm this link and what do you have to say to those who try to deprive you of it?

Faith does not belong to anybody – I don’t understand why this is even a debate in the first place. I felt the urge to talk about God and religion because I’ve always felt so excluded from it and didn’t understand why. I was 9 the first time I heard that trans people and homosexuals burn in hell because of who they are. Family members explained this to me just like you would explain why the sky is blue to a child. It’s something that traumatized me – I didn’t even know who I was but there was so much violence surrounding my existence.

Somehow, it feels like society on a very large scale is more okay with a man being a terrorist or a rapist than a trans woman being faithful, a good person or even existing in the first place. I never understood how men who were violent or rapists or terrorists or ill-intentioned bastards somehow felt legitimate in using religion as an argument to justify the wrong, dark, twisted things they would do. How do people still let that happen today?

To be seen, to release an EP, and to finally be able to live off your passion… What should we wish for you?

More! More love, more blessings, more inspiration, more beauty, more talent, more money, more passions To keep on being as inspired, legendary, talented and beautiful as I am today, forever! Inchallah.