By Moussa Saleh

Translated by N.H.

Copy Editor: Eliza Marks

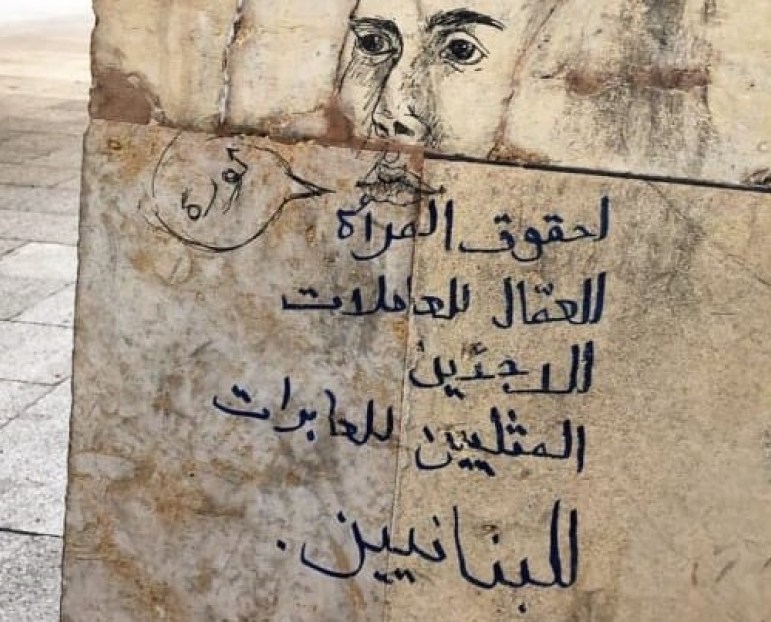

Images: Downtown Beirut, Lebanon

About 35 people set out from near the Riad al-Solh1 statue in Downtown Beirut, but by the time they returned after two hours of marching through the capital’s main neighborhoods, that number had grown to thousands. The movement expanded quickly to include road blockages and protests in the suburbs of Beirut, which further increased the determination of the protestors downtown and throughout the country. These protests were unlike any Lebanon had witnessed since the end of the Civil War. Tripoli united with Baalbek, Akkar with Nabatieh, Tyre with Beirut, Aley with Chouf, and many other areas. They all came together to form a tapestry of revolutionary protest against the sectarian regime, which has long exploited the resources of Lebanon and its residents to increase its oppressive power.

This article examines the ways in which the LGBTQ community participated in the protests in Beirut, and explores the link between the demands of the LGBTQ community and those of the revolution.

Downtown Beirut, Lebanon

LGBTQ Presence in the Revolution

A civil, non-sectarian revolution like this is new to Lebanon. In addition to successfully destroying barriers of fear and intimidation constructed by sect leaders, the revolution has witnessed a large LGBTQ presence, unashamed and unafraid. Their presence was not due to the fact that Lebanon is a so-called “liberal society” that supports personal freedoms in the region, an image that some LGBTQ organizaitons export to neighboring countries and worldwide. Rather, LGBTQ presence in the revolution was driven by copious amounts of pent up anger, an extension of the collective anger of the Lebanese people.

Some people attempt to reduce the suffering of LGBTQ people to discrimination on the basis of gender and sexual orientation. This notion is both evident in peoples’ mentality and reflected in how they relate to social and political matters to identity, for our different preferences, identities, and sexualities are political issues. But people with non-normative sexualities face more than just everyday discrimination and state-sponsored hatred—especially since the implementation of Article 534 of the Lebanese Penal Code, which criminalizes “unnatural sexual relations”2. We are also refugees, differently-abled, poor, domestic workers, foreign workers, sex workers, and we have different academic capabilities. We do not face oppression only because we belong to the LGBTQ community. Our political issues are all connected under a socio-political regime that must be brought down.

Downtown Beirut, Lebanon

Is Sexuality a Priority in the Lebanese Revolution?

There were many phrases written on the walls of the city, Riad al-Solh Square especially, that stood out: “Sodomite is not an insult,” “Gays for the revolution”(which one protestor later erased), “Lesbians against racism.” One corner of the square was adorned with the words, “Transgender people for the revolution.” Some were brave enough to express their identities and sexualities inside the square. One of the driving forces of the revolution are bold claims like these that call for visibility of and space for LGBT peoples, and the claim that they, too, are an essential part of Lebanese society. We are revolting against a patriarchal and corrupt system, and our battle will not be successful or complete without the presence of all segments of society.

This seemingly basic point — that all segments of society are essential to its identity — has always been a topic of debate, whether in the square through continuous discussion circles, social media platforms, or the officially banned gay dating app “Grindr”. Some believe in the importance and necessity of visibility, while taking all security precautions of course. Others argue the opposite, saying, “No, this is not a priority. We want economic and political demands. As for our identities and rights as non-normative individuals, that will come later.”

This second position is common to movements that advocate for marginalized groups, such as the feminist movement or movements that demand the rights of foreign workers. They say there is no room for this now, but we exist on all fronts, defending our livelihoods, education, health, future, and sexuality. But there is no room for compromise or focusing on some issues over others. As the intersectional feminist movement in Beirut says, “Every issue is a priority, and solidarity is the solution.” In other words, those who prioritize demands related to livelihood, fighting corruption, or overthrowing the regime without recognizing that sexual and gender rights are part of that, are bound to fail.

Downtown Beirut, Lebanon

Multiple Issues, Unified Struggle

These demands are all connected in their struggle against patriarchal, capitalist, colonialist systems, and in their attempts to destroy those systems through cooperation and solidarity. For example, failure to conform to traditional ideas of state-approved gender is enough to be denied job opportunities in Lebanon. As for healthcare services, there is a whole group of people whose right to hormone treatment is disregarded. If you further consider the racism of Lebanese state discourse, which reproduces systematic mechanisms that control the discourse of the people, you will find that femme male refugees and butch female refugees are among the most vulnerable groups. They are subject to torture, harassment, and ridicule in official state institutions. All of this is to say that sexuality is not separate from revolutionary demands for fair job opportunities, free healthcare, and the elimination of corruption in state institutions.

Sexual and gender identities and expressions (before the emergence of labels), whether innate or a choice, must be protected and honored by the law that regulates our society. Diverse sexualities are “natural” and form an essential part of our daily lives and struggles against our families, society, and religious and political establishments. These concerns must be a pillar of the revolution that should not be trivialized or deemed “negotiable”.

The moment the Lebanese people rose up against a sectarian regime—one that revolved around convincing the masses to follow leaders who espoused religious and sectarian beliefs based on references and traditions that criminalize non-normative sexualities—they chose to head in the direction of a secular civil state, one that does not leave room for discrimination against people because of their sexual practices or gender presentation. The society we seek is a secular, feminist, civil society based on respect for others without exception. It is a society that is inclusive of refugees, protects the rights of foreign workers, and respects the civil and political rights of individuals without any discrimination or persecution.