Words by Sami Abd Elbaki

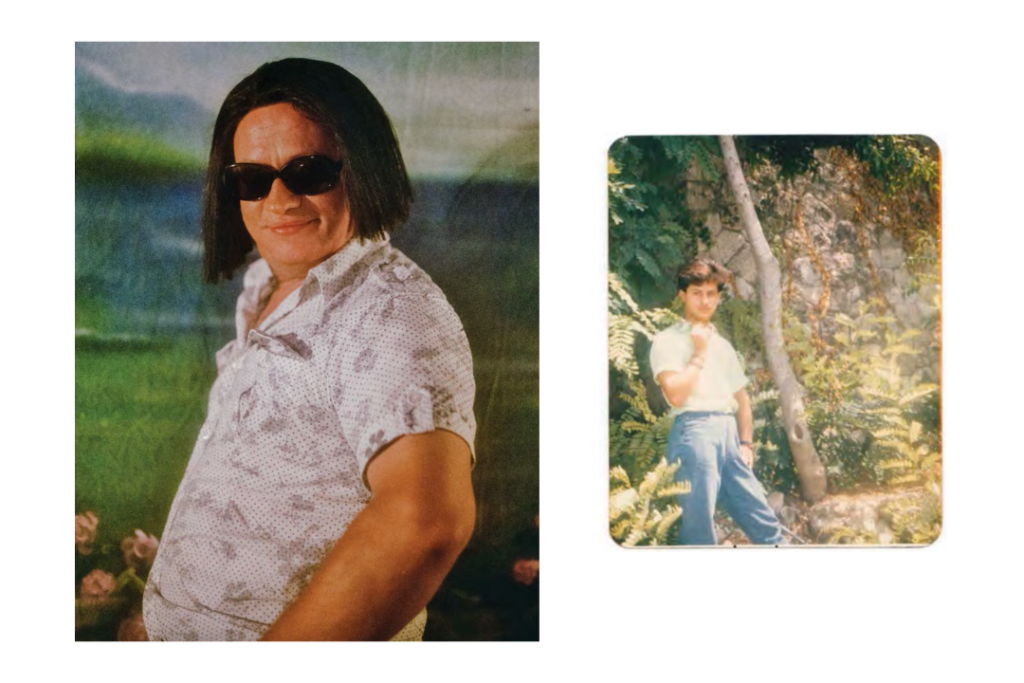

Featured image: Snapshot of Mama Jad – Taken by an unidentified photographer – Date and location unknown

Image courtesy of Mohamad Abdouni and the Arab Image Foundation

This feature is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Lebanese artist, photographer, filmmaker, and curator Mohamad Abdouni is driven by curiosity and a deep commitment to authenticity. Currently based between Beirut and Istanbul, he follows what feels true, allowing his work to evolve organically.

In 2017, Abdouni founded Cold Cuts, a magazine that chronicles queer histories from the Arab world. He describes it as a printed extension of himself and his creative journey. Through Cold Cuts, he explores personal affinities, collaborates with diverse voices, and tells stories often left untold. While the magazine is rooted in queer perspectives, Abdouni resists labeling it too narrowly, preferring to let it remain open and fluid.

The fourth issue, Treat Me Like Your Mother, documents the lives of ten trans women in Beirut. One of the first archives of its kind in the Arab region, it features around 300 images portraying the trans-feminine experience in postwar Beirut during the 1980s and ’90s. The title, drawn from one of the women’s stories, is a plea for respect—and the book delivers stories of heartbreak, humor, resilience, and unapologetic truth.

The project was developed in collaboration with Helem, an LGBTQI+ NGO in Lebanon. Helem played a crucial role in connecting Abdouni with the women, supervising interviews, providing legal guidance, and ensuring the participants’ safety throughout the process. Many of the images featured in the book are personal photographs shared by the women themselves. These now reside with the Arab Image Foundation, which has also contributed images from its own archive—offering a rich resource for researchers and creators.

Though the book was nearly five years in the making, Abdouni sees the journey as ongoing. Since its 2022 publication, Treat Me Like Your Mother has been exhibited internationally—at venues including Institut du Monde Arabe’s Habibi exhibition, MINA Image Centre, the Biennale de Lyon, and Art Basel. The project has also been adapted into a feature film, set for release in 2024, which includes a cinematic score and the recorded voices of the women featured.

We sat down with the mind and heart behind the project, Mohamad Abdouni, to discuss the book—and what comes next.

How did the journey of Treat Me Like Your Mother start?

I got a frantic phone call, very late at night, from Lebanese drag queen and dear friend, Anya Kneez. She’d gone to a storytelling night at Station in Beirut, which now seems quite fitting; Station ended up being the place where we held and organized all the interviews and shoots for the book. And, this is where Anya met Mama Jad, one of the women featured in the book, when she took the stage and started telling stories about her life and growing up in Beirut in the 90s.

Anya was emotional about the stories themselves, and also that she’d never heard these stories despite being very active in the community. It was a mix of emotions. Then and there, we decided to at least attempt to record some of the histories of trans1 communities in Lebanon.

Almost five years later, I realized that my passion for recording these stories was also related to my own identity. I experienced a sense of disconnection with modern political conversations on gender. I felt alienated from these conversations and they confused me much more than they provided clarity. These women simplified things in ways that made me understand myself much more than modern political conversations around gender.

On the left: Mama Jad – Beirut 2019 – Photo by Mohamad Abdouni

On the right: Mama Jad, “In this one, she had just lost the first person in her life. It was about 1983, 1984. She was fourteen maybe going on fifteen. She was asking herself what will become of her after losing this person. I feel like Jad in this photo is just like the sea behind. Nobody knew where she was going or what she wanted. Everyone used to look at her with shame because she brought shame to her family. And she didn’t love herself. She was covering her body in this photo. She was wearing decent clothes. In this photo she wished that a wave would come and swallow her into the sea so she wouldn’t have to go through what she had just been through back then and now. When I look at this photo I think I wish she had died. But I can tell her that I love her, and she had beautiful hair. I wish she could be able to forgive”. Jad kisses the photo.

When you first started documenting, did you have any idea of how the project would grow?

Documenting was the intention of the project, but I didn’t know how it’d grow. I generally just throw myself into something and let it develop into whatever it needs to be developed into. I try to learn first for myself, and then figure out how to package the information in a way that makes sense to others who might also be curious.

When we first started, we just wanted to record those stories so they wouldn’t disappear when these women were no longer with us. Then came the archives. These women started sharing their personal archives with us, so generously, so the publication turned into an open-access archive. Every exhibition that we did around Treat Me Like Your Mother had a completely different curatorial approach, to showcase different things. I tried to play around, to show different archives, to blow some things up and make other things small.

What was it like when you first went through the photos, after hearing the stories?

It was almost unreal, in a way, because the stories themselves were unreal, and especially stories that happened in public spaces.

You think: how, when, where? What are these odysseys you took? What are these myths you are sharing? Then you see photographs, and it’s not like you needed visual proof in their stories, but you see “that’s how.” It added color and fashion sense to those spaces, and a sense of reality to something that just seemed so surreal to hear about.

On the left: Kimo, Beirut 2019 – Photo by Mohamad Abdouni

On the right: Kimo, “I met the guy who took this photo at the Luna Park. Or it was my nurse friend who took them. It was in Harrisa, i think it was, or another town outside Beitut, i don’t know remember exactly. It was around 1989. I used to have long Hair and I would dye it sometimes. I love fashion catwalks and i love posing. I love photos, i have a lot of them. They’re wear torn. When my wife found out about the other man she tore up a lot of my photos”.

Notably, the stories are also written in Arabic and translated into English. What was the thought process here?

We didn’t edit the texts. The book is intended to be read in Arabic, and we struggled so much with the clumsiness of the English. In the end, we decided to keep the clumsiness; it’s not a smooth read in English, but it’s more truthful.

You also took additional photographs for Treat Me Like Your Mother, which almost remind me of old Lebanese photography studios. What role did these play in the project?

The point of those photographs was to give each woman a day of pampering, in a way. We had these racks of clothing that were donated by people in the theater and fashion designers from Lebanon, and Anya helped with the styling. And Andrea, another drag queen from Lebanon, did their hair and makeup. In the end, each woman had complete control; they showed us how they wanted to look.

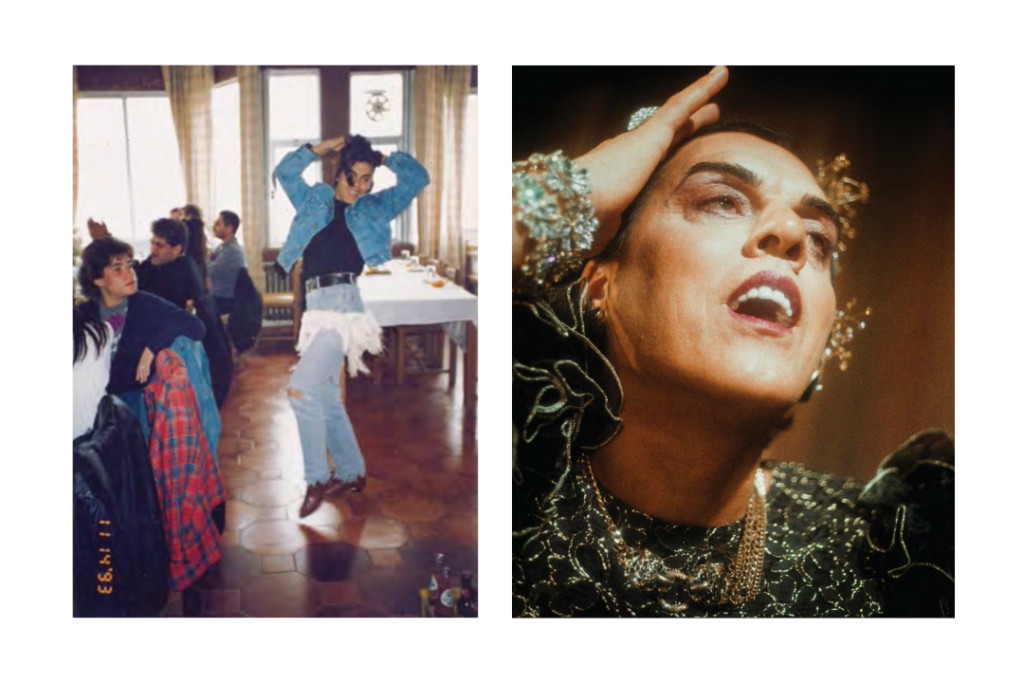

Snapshot of Em Abed at a Halloween night at Saframarine where they won first place – Taken by an unidentified

photographer in 1996 in Kesrouane, Lebanon

On the left: Snapshot of Em Abed at a restaurant – Taken by an unidentified photographer in 1992 in Kesrouane, Lebanon.

On the right: Em Abed – Beirut 2019 – Photo by Mohamad Abdouni.

How did the women respond to the book’s publication?

There were so many beautiful anecdotes. Em Abed has become like an older sister to me since the beginning of the project, and the first time I showed her one of her portraits, maybe four months after the shoot, I went to her house with her portrait framed in A3 size. I showed up for coffee and was like, I got you something. She said they were nice and continued to make the coffee. I thought it was a lackluster reaction. She finished making the coffee and was pouring it, and only then did she realize it was of her. She picked it up, dropped the coffee, and started talking about how gorgeous she was. And then, she complained about why I got it framed and why it was so big. How can she put it in her photo album?!?

I did another project more recently called “Extended Archives,” in which I used AI technology to fill in the gap in Em Abed’s (أم عبد) archives. She had no portraits from when she was 19 or 20. I was born in 1989 and decided to recreate a portrait of her from that year as if I had taken the portrait. I printed it on a 10×15 cm photo paper. Again, with no context, I went to her place for coffee and gave it to her. She just looked at it, looked at me, and went, “See how beautiful I was back in the day?” I was like, “That’s not true. That’s not even you!”

The project also became so immersive, including video and sound. How did these elements come in?

A lot of curiosity from people to hear the women’s voices and how they told their stories. Four of the ten women we worked with on this project were comfortable having their voices recorded and used, so, with their consent, we created an audiovisual installation. We did this first for the Lyon Biennale. We developed an exhibition video installation further for the MINA exhibition in Beirut and had some wonderful people play the score live. They then worked on the score for the film: Fadi Tabbal, Charbel Haber, and Postcards, so Julia Sabra, Pascal Semerdjian, and Marwan Tohme.

It was probably the most magical night of my life. All the women, except for two or three, were able to be there. I just held back tears the entire night. They were like Spice Girls. Each one of them had her posse of fans around her, making them sign books and asking for stories. It was just glorious to see.

From the MINA exhibition, it became clear that people received the project in a completely different way than the book, and it was worth developing it into a feature-length documentary. It will finally premiere in the coming months [early 2024] and do a festival circuit.

When you read their stories, they come across as harrowing tales. But when you hear them tell them, you regain some of the comedy they’ve put into their narratives. Maybe it’s a way of coping or a sign of acceptance, or a million other things. You lose that when it’s just text. But the film, in a way, brings audiences back to the written text, because it features only four of the ten women. The elements all circle back to one another.

Can you say more about how the film score (soundtrack and sound design) developed?

I reached out to Fadi, Charbel, and Postcards to create an entire score, and Riwa Phillips edited it. I gave them copies of the book, and they composed an hour and a half score made up of six or seven pieces. We worked together with such beautiful synchronicity. We took the different sounds and just played with them. Everything was chopped up; it plays like a producer mixtape, or like a very fucked up DJ set.

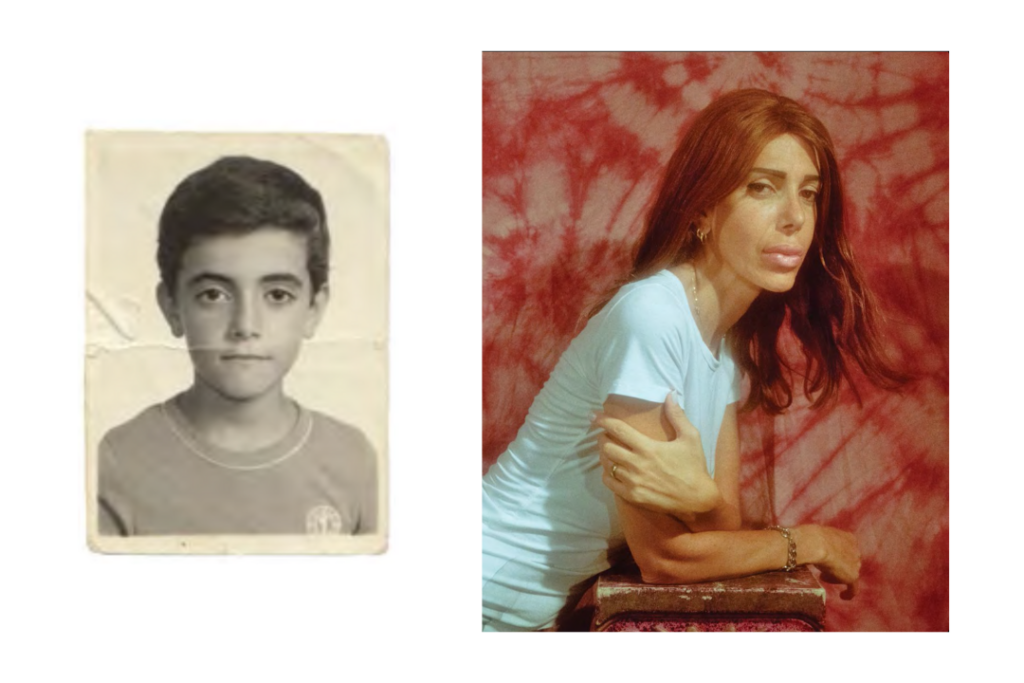

On the left: Antonella aged twelve

On the right: Antonella – Beirut 2019 – Photo by Mohamad Abdouni

You’ve been working on the project for almost 5 years now, and it seems it’s not entirely over. How has your relationship to it developed?

Of course, recording these histories and archives and making them accessible has been really important. But again, there’s a more personal connection; that’s why I’ve kept working on it for so long. I discover more about it as life progresses and I get some distance. My intentions might’ve been purely curiosity, but I’ve been able to learn more about the why.

Are there any other comments about the project that have stuck with you?

I was astounded by how many people read the book the day we released it as a free PDF, including people we didn’t know. There were also an insane number of DMs. We got one long message from an Algerian trans woman, written in Arabic. The profile picture was a cat, and there were no posts or followers. They said they never could’ve imagined they’d see these images or read this book in their lifetime. It also showed how wide Cold Cuts’s following was in the region.

What’s next for you?

The film will be released this year [2024]. And, I’m currently co-writing with Mohamad Yassine, a fictional TV series with ARTE that I’ll also be directing next year.]

Em Abed with Charles and Malek – Beirut 2019 – Photo by Mohamad Abdouni