Words by Eliza Marks

Artwork by Haitham Haddad/Studio MNJNK

This piece in a collaboration with Cinema Alhambra

⚠️This piece contains conversation related to sexual violence, gender violence, and homophobia.

As the war on Gaza rages on, alongside other colonial campaigns throughout Palestine, the “unprecedented” has been livestreamed through our mainstream media and social media. Throughout this most recent intensification of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, we’ve witnessed the indiscriminate killing, abuse, and starvation of Palestinians; gross bombing and destruction of infrastructures and institutions in Gaza and the West Bank; abduction and detention of many without just cause or charge; and advances in the seizure of homes and land, among other offenses. These actions have occurred alongside the unapologetic display of genocidal actions and intent of Zionist leaders, military, media, and “civilians.”

We’ve also witnessed the largest scale of centering of Palestinian voices, through citizen journalists, lawyers, academics, civilians, and activist pages; international solidarity activism with Palestine; and actions that are shaking capitalist and political systems. And, while it may have only symbolic significance, we’ve seen Israel being called to account by South Africa’s case at the International Court of Justice. This is a rupture.

As Israel flails to win public international support for its colonial project, the pinkwashing strategy it’s used for decades has crumbled. In its 2020 article, “Beyond Propaganda: Pinkwashing as Colonial Violence,” alQaws argued that pinkwashing is a symptom of settler-colonialism, a propaganda effort and branding strategy that “aims to rebrand Israel as a liberal and ‘modern’ state in the face of the growing Palestinian solidarity movement” by characterizing Palestinian society “pathological homophobia,” and therefore “undeserving of solidarity.” Not only does it further the aggressive settler-colonial project, but it seeds divisions within Palestinian society that “compels queer Palestinians to view themselves through the lens of victimhood and powerlessness.”

This article with Haneen Maikey1 and Musa Shadeedi2 reflects a conversation that took place over the span of two months. It seeks to analyze particular cases where pinkwashing was invoked (and failed) since October 2023, and to frame it as part of the larger colonial project’s targeting of bodies. In the process, it reflects on the utility of “identity politics” in organizing today, and what this period might mean for organizing in the future.

This conversation is edited for brevity and clarity. Still long, below are the sections to make it easier for you to navigate:

- Identity Politics and the Colonial Project

- Shifting Valuing Around Gender and the Body

- Problematics of Solidarity Politics

- Values and Organizing “At the Time of Genocide”

Eliza: Before starting, Haneen, what do you think analyzing pinkwashing at this current moment can show us? How did you experience and confront this particular side of the colonial project?

Haneen: In this painful context, amidst one of the most evil colonial acts and genocide in our history, we are seeing the discourse and framework of pinkwashing – alongside sexual and gender politics, in general – used in the ugliest ways possible by Zionists. It would be useful if the act of debunking pinkwashing during this genocide could also present a way to talk about us, our experiences as queer individuals and communities living in Palestine.

Queer communities in our region (and other places) have always been weaponized during wartimes by imperial powers. We saw this happening in Iraq, Palestine, Afghanistan and other places. Today, there is no doubt that pinkwashing, as well as LGBT rights, transform into direct tools for the killing of Palestinians. Pinkwashing discourse is being used at this moment of history because it serves the colonial aspiration to erase Palestine, Palestinians, and our history. Nothing new to the Zionist project.

For me, being Palestinian and/or queer means always living inside the tension of what is more urgent, and I intentionally do not use “important.” And now, with the total breakdown of liberal frameworks like Human Rights, LGBT rights and inclusivity, as well as identity politics, I believe this tension is where things are created and potentially liberated, and not just a sight of “confusion.”

Pinkwashing was always part of the Zionist colonial violence, and this is why decolonial aspiration — both in discourse and praxis — was always an important part of alQaws work. We prioritize politics over identity because that was our lived experience, and de/anti/colonial praxis centers this and aspires to build a living movement. Maybe it is because of this approach that Palestinians organizing through other lenses (feminist, human rights, political) have found it challenging to express solidarity with us. Feminist movements have ridiculed us for organizing parties to build community, saying we weren’t “political enough,” and some have ignored our political activism, repeating the myth that we were not part of our society. Everyone seemed to have an opinion about our activism.

But from the beginning, we saw how pinkwashing works to isolate queers from their communities, though many of us have already been deprived of our families and community. Pinkwashing, as a colonial tool, is evil.

IDENTITY POLITICS AND THE COLONIAL PROJECT

Eliza: To get into the issue of “identity politics,” maybe we can discuss the image of the Zionist soldier standing atop the rubble of Gaza with a rainbow flag, with “In the Name of Love” written on it in English, Hebrew, and Arabic. It has circulated heavily throughout the early months of genocide. What does this image invoke for you? How has “identity politics” been capitalized upon here and in other colonial projects?

Haneen: Previously, Zionist’s pinkwashing was based on “human rights” – suggesting they are progressive or democratic, or care about the “gays” – while at the same time aiming to depict us as backwards, victims of a set of imperial myths stating that homophobia is rooted in our culture. Now, they use pinkwashing while stepping over every human right framework or value. Through their genocide, they have completely destroyed the basic framework in which their pinkwashing claims to be based on.

Pinkwashing, in this image, conveys the idea that “We – as Israeli gays – are proud colonizers. We are proud of dancing in your blood and to be part of the Zionist killing machine.” Their pride of being gay has transformed into pride of being “killer gays,” active participants in one of the horrors of the century. The real meaning of this sign is not the love, but simply “In the name of Genocide.”

Musa: In some ways, this image reminds me of the American army in Iraq, which claimed that part of its project was to liberate “gay Iraqis” to justify its invasion. For me, the rainbow flag and what it represents is colonial from the beginning, not only because it’s an Israeli soldier holding it now in Gaza. And, when it’s raised in colonial embassies across the region, it triggers violence against non-normative local people like Karar AlNushi, who was assassinated in Iraq one month after the US consulate raised the rainbow flag in June 2017.

After the invasion, we saw Western identity politics being imported, taken up, and used against local populations. HRW published a 2009 report in which they interviewed 24 people who did not identify as mithleen or mithli – they identified themselves as gays, an identity that entered Iraq after the invasion in 2003 – and argued that the US occupation authorities “tacitly supported” some militia attacks. We saw an example of this with the corpse discovered with mithli inscribed on it with a knife around that time. Militias used the raising of the flag, the term “mithli” and US pinkwashing to justify the “gay” violence and killing campaigns.

I wonder if Western identity politics around sexuality and its symbols were more beneficial to the Iranian-backed militias in Iraq than to their “victims,” whether it has made it easier for militias to determine who to attack and kill, and how to justify it. I explained the risks to western officials and NGOs, but they didn’t seem to care, and they continued to raise it again and again across the region.

Even people raising the flag at Palestine solidarity protests cannot decolonize it. Joseph Massad notes that anti-imperialists continue to adopt imperial epistemologies and ontologies,3 but, as Audre Lorde wrote, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”4 While the tools of the colonizer can be helpful, they can’t cause any radical change; we can’t decolonize the products of colonialism.

Haneen: We should stop using identity politics after this image – it’s the lowest use. That Israeli queer communities ran to declare loyalty isn’t surprising, and it exposes their active role in the killing machine all along. Hebrew-language media has been praising gay soldiers, suggesting they will win a place in society after the war. But it’s not about gay rights and acceptance; it’s about proving loyalty and playing an active part in the Zionist machine. Previously, we saw these actions through propaganda mainly, and now this image roots pinkwashing in the actual killing and genocide, further showing how pinkwashing is colonial violence.

Building on your example in Iraq, we can see how identity politics in Palestine is used by the colonizers, first, to declare loyalty in the name of that identity, and second, to “label” and “paint” resistance forces and male Palestinians in the most homophobic way. It exposes a deep contradiction in the psyche of the colonizer, gay or otherwise: the same identity politics used to boost their pride in being Israeli and Zionist is used to shame Palestinians. Pinkwashing is homophobic, outdated, and backward. And, the ways that Zionist queers are capitalizing on this contradictory logic to show “we can also kill” is a gross statement that their gay identity is more important than humanity. Imperialists will use every identity we have to isolate us from our land and our own communities, and to further make us vulnerable and “easy victims.”

SHIFTING DISCOURSES AROUND GENDER AND THE BODY

Eliza: We have also seen numerous images and testimonies evidencing the stripping, abuse, torture, and slaughter of Palestinian bodies, and the way that are “put on display” by the colonizers. Such actions are not new, but the surrounding narratives certainly are.

Musa: The behavior of photographing naked prisoners without their consent is weird, but the imperialist soldiers seem interested in it when they invade or occupy any place in the global south, as we saw with Abu Ghraib. It must be fulfilling a psychological or psychopathic need. I assume it affirms to themselves that they’ve achieved a high level of humiliating others, or that the taking of these images is part of the act of humiliation. Bernard Haykel explained that, “being on top of each other and forced to masturbate, being naked in front of each other” was part of the systematic torture, and when asked about committing these behaviors, one of the soldiers said simply that “this is how military intelligence wants it done.”

Haneen: In most of these images, it’s clear they want only to further humiliate Palestinians. Humiliation and stripping of bodies is a colonial routine in Palestine, but thinking more generally, it shows how gender and sexual violence is inherent to the colonial project. Pinkwashing is more than propaganda; it’s gender and sexual violence inflicted on us.

Over the last 20 years, we’ve failed with talking only about infants, women and elderly, and left male bodies to the side. With the exposure of this sexual and gender violence during this genocide, we are seeing a huge shift in reclaiming the relationship to these violent and chauvinistic acts with statements like “we love our Palestinian men.” We are reconsidering the positionality of bodies, and with that, how they are valued. This shift is historical. People are telling men that “it’s not humiliating” and “we don’t think less of you” because of it. Like the inefficacy of pinkwashing images we discussed above, people are doing the opposite of what I assume these images and acts intended to do.

When political Palestinian organizing and liberation struggles say you should hide these things, rather than saying we love you despite it, they’ve failed. There’s hope that society will, at some point, say that about queers and about any other identity, choice and behavior that was labeled as shameful. It’s more complicated than simply talking about “acceptance,” but maybe resisting the shame and pressure to hide is where we need to go when pushing for liberation.

Musa: This shift is apparent in the testimony of a man released from the Naqab prison, about sexual torture, harassment, rape he witnessed there. While men are more able to speak of these things, lately, there is also documentation of Zionist sexual torture of Palestinian men even before the establishment of “Israel.” For example, in his 1938 testimony, Palestinian political prisoner Subhi Al-Khadra wrote about Palestinian prisoners being sodomized by the soldiers.5 This reclaiming of narratives does not minimize those tortured but the torturer, who is using homosexuality as a punishment. These actions seem like the most directly homophobic expression of colonial power.

Haneen: While female prisoners have written many books and given testimonies about sexual violence in prisons, now – as the genocide is being livestreamed – what’s changed is how we are dealing with and understanding it, and how we are standing against the stories they try to force on it. Like you said, claiming to “save” women and gays while using these strategies reveals that all of this is empty statements and politics.

PROBLEMATICS OF SOLIDARITY POLITICS

Eliza: Queer solidarity actions have multiplied amidst the larger wave of solidarity with Palestine. I’d like to think about a couple cases of “queer solidarity” through a critical lens to reflect on what meaningful organizing and solidarity looks like.

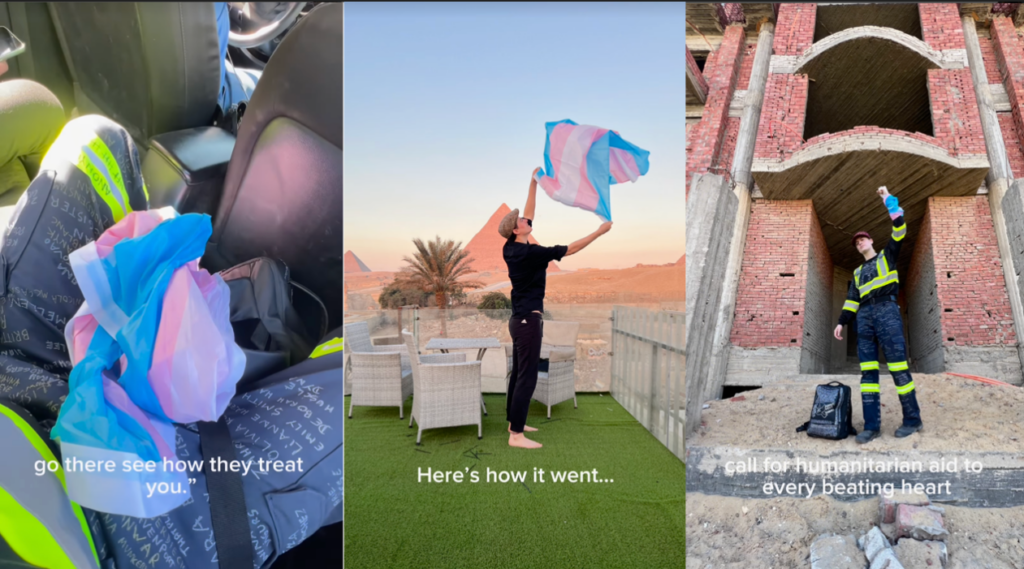

To start this conversation, and because we already spoke about the rainbow flag, I’ll mention a video in which queer activists and allies – from the region and American – went to Egypt to distribute aid to Gazan Palestinians, trying to debunk the claim that “Gazans will kill queer people” and other pinkwashing tactics.

Haneen: I have always felt any reactionary solidarity is limited and, though it seems harmless, plays on the same frame of pinkwashing that centers “homophobia” as the measurement of progression and backwardness. That people are surviving genocide is now measured by homophobia is insulting and irrelevant. And, the propaganda elements of countering Zionism in this way also “denies” the homophobia that exists in my society. I consider these actions as a distraction to our endless work to combat Zionism and pinkwashing.

Musa: In some way, this shows that pinkwashing in the West is changing. During Sheikh Jarrah in 2021, there were these pictures of an Arab/Palestinian man wearing the keffiyeh kissing a Jewish man in a kippah, the sort of “love is love” idea that depoliticizes the Zionist occupation. Now, pinkwashing has become an invitation for genocidal support; so we see LGBT movements that are explicitly for Palestine, but again, you can’t decolonize identity politics. This rise in LGBT solidarity with Palestine is a response to shifts in Zionist rhetoric, which transformed pinkwashing from a politics of covering crimes to a politics of justifying them. But (Western-style) solidarity politics is always tied to visibility. The resistance has taught us something about passing politics – whether through tunnels or with masks – as an effective tool of gaining liberation. Along these lines, we are seeing the ways in which visibility politics, while effective in some cases, has its limits. We are entering a new age of passing politics.

Haneen: The queer community in Palestine was never outside the colonial context. Another myth that pinkwashing paints is that Palestinian queers have access to Israel, or they could be accepted despite their Palestinian identity. Like a friend says, “does the Wall have pink doors?!?” There is a fantasy of crossing colonial barriers and then reality hits: even if you can cross, nothing will change, the colonizer-colonized dynamic will still be at the heart of it. Israeli LGBT groups proactively reached out to gay Palestinians with delusional promises that ended up stripping our community further away from our own society, and at the same time failing of course to changing the reality of violence.

When people contacted us, unlike some Israeli groups, we never made promises. We weren’t neglecting queer Palestinians, but being realistic in admitting that we have no power as an anti-state, anti-colonial organization. And, as a political stance, we can’t work with Israeli Zionist groups, or worse, the intelligence forces. Even if you were able to cross colonial borders to flee some horrible violence, the next steps are more horrifying. Basically, Israeli LGBT groups – who claim to help and save Palestinian queers – are working closely with the shabak. After you were cleared to be helped by some LGBT groups, the next step is an interview about their experience with their families. They would then out people seeking assistance to their families so they would never be able to go back, and when the residency permit ran out or never came, they’d never be able to return.

Eliza: More problematic than the above example, I wanted to mention the Tel Aviv International LGBTQ+ Film Festival, which ran in December 2023. It actively incorporated the work of some Palestinian directors while vehemently denying the resistance, saying “These are not freedom fighters, these are abominable killers.” Obviously, they are deeply implicated in pinkwashing campaigns, but I’d like to discuss the politics of participating in such events, especially at this time.

Musa: First, I want to address the claims in the statement. Freedom fighters are throwing “LGBT people off rooftops” while shouting “Allahu Akbar”? They should just “reach out for peace”? It is Islamophobic, and simply assigning what ISIS to Hamas. It misses what freedom fighters, all over, are fighting for and the means they use. It draws on the names of so many groups that are fighting for their freedoms, while denying the occupied and oppressed peoples’ right to resist. And lastly, they bring in many unrelated and unproven points.

It’s unfortunate that this cinematic pinkwashing uses Palestinians – characters, directors, staff – as a tool for their pinkwashing both in the festival and media. They gave a prize to a queer Palestinian director this year, amidst the genocide. And in 2017, Palestinian directors Maysaloun Hamoud and Samira Saraya, who participated in the festival in different capacities, were cited by Israeli media to defend the festival against pinkwashing allegations.

Haneen: TLVFest, the international LGBT film festival, is an example of the hypocrisy of LGBT Israeli organizations and groups. They are not worthy of any attention, but historically, they’ve had a major role in pinkwashing. We were the first to challenge them in an organized campaign calling on international LGBTQ filmmakers to boycott it. Since then, the first sentence of the opening statement of their website is about how much they care about Palestinian queers. Their work over the last decade and their statement about October 7th demonstrate how backward, Islamophobic, and racist their leadership is. They are not just genocide deniers, but the ultimate liberal, soft Zionist project leading propaganda.

Two additional things are worth mentioning here. First, they actually organized their festival during the genocide, claiming their hearts are broken to what happened on the 7th of October. They repeated the backward propaganda you already mentioned while demonstrating indifference to the tens of thousands Gazans killed, including queers. Second, they gave a special prize to a Palestinian queer filmmaker. I keep thinking about this situation: how on earth could a Palestinian filmmaker accept such an invitation and prize during “regular” times, let alone during a genocide? This shows us that queerness is an empty identity when there aren’t common political commitments.

When someone told me Cinamji hosted the same filmmaker who participated in the recent TLVfest earlier in 2023, I thought about withdrawing from this engagement. This feeling will never go away. The argument of screening every film, even if we do not agree with it, is politically outdated. I think that choosing to host Israeli-funded films despite our calls for boycott, and then claiming to screen them because they talk about Arab queers and discussing them through an anti-colonial lens, distorts what decolonial praxis is and indirectly promotes pinkwashing.

Musa: I agree that organizing programming around the “Arab queer” identity is orientalist. There was a problem when most of the queer organizing entities in the region – until 2017 or 2018 (when Cinamji was formed) – were focused on the Western queer films that they agreed with, and mostly without discussions. This gave the false representation that non-normativity can only exist in “the West,” and didn’t allow them the space to develop a queer regional criticism.

But I think it’s important to screen films – particularly Arabic-language ones related to sexuality and gender, and even the ones we disagree with – and have discussions to feminist, queer, and anti-colonial modes of analysis and critique. These forms of knowledge are so limited, particularly in Arabic, and this format allows viewers to reclaim power over the screens. Screening Israeli-funded Palestinian films in these settings, where the goal is to discuss and develop critique in a (semi)private setting, saves us from inadvertently protecting these tools of pinkwashing. This doesn’t violate the boycott, in my perspective, but it enriches the arguments of the call, overall.

I don’t know how, but I still have hope for change and believe we need every voice to liberate and decolonize local desire. I hope this Palestinian director finds his place in this struggle, and I know many people have (intentionally and unintentionally) participated in projects and documentaries that have been used for Israeli pinkwashing, and later become anti-pinkwashing activists. I learn a lot from this growth.

VALUES AND ORGANIZING “AT THE TIME OF GENOCIDE”

Eliza: It feels like, right now, the world is questioning its values, the meaning of justice and the institutions that claim to represent it, and practices of effective organizing. Considering the above, maybe we can reflect on what anti-colonial, anti-imperialist organizing looks like, moving forward.

Haneen: The most popular “critique” of alQaws was part of the Israeli LGBT movement pinkwashing efforts that repeated the myth that we neglected Arab queers because we were too “busy” fighting colonialism. This was the core of local pinkwashing, a violent tactic of colonialism that contributed to the fragmentation of our movement, especially when Arab queers, activists, academics and artists, repeated this Zionist, homophobic argument. It was as if the people inside alQaws were not queer and oppressed and facing the same oppression. (Interestingly, in other critiques, we were not Palestinian enough.) Some famous academic texts – which are now celebrated in queer circles – are based on this pinkwashing argument.

I struggle with the fact that our discourse may have contributed to the diminishing of core values. During my years of organizing, I was astonished at how quickly groups became “value washed.” For example, when queer communities in Palestine spend hours discussing privacy rather than welcoming new members and committing to outreach. It was as if the idea of safety was more important than respecting people who may just be confused.

In the shadow of colonialism and all of these systems, we need to reflect on our values, how we protect them, and how we resist becoming just projects or discourse. We are humans who are meeting each other and having these interactions, and this should be organized by values rather than political discourses.

Musa: In Iraq, the US said they were liberating gays, but at the end, they said it was “a luxury for the average Iraqi to worry about homosexuality,” denying the series of killing campaigns against them. In 2003, Bush also said there would be no more “torture chambers and rape rooms” in Iraq, referring to the Iraqi regime use of sexual torture in prisons, and shortly one year after, the images from Abu Ghraib surfaced. Colonizers are obsessed with sex, particularly non-consensual “exotic” Oriental sex and “sexuality,” but not with the rights of the people.

I think we need to throw western politics away, or at least draw on it more critically and selectively, to develop a way of organizing that is based on our own history and experiences. This is what revolutionary and liberatory organizing looks like.

Every person or entity that has applied pressure to stop the genocide is important. This caused Israel to declare one of the biggest homophobic digital campaigns I’ve witnessed in my life. But this is only the beginning; Israel ruined any hope for decolonizing queer identity politics when it used it to justify genocide. If we want to make a radical change, we need to change our structures and strategies. We need to go back to our Islamic history to see what has worked and develop new ways forward.

- Haneen Maikey is a Palestinian feminist queer organizer and co-founder and former director of Palestinian civil society organization, alQaws.

- Musa Shadeedi is an Iraqi writer and researcher, who focuses on desire through anti-colonial, Islamic, and queer lenses. He’s published books, including Homosexuality in Invading Iraq (2020), and articles on different platforms, including My Kali, Kohl, and 7iber.

- Joseph A. Massad, Islam in liberalism, (University Of Chicago Press, 2015), p. 256.

- Audre Lorde, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house, 1985), In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, (Crossing Press, 2007), p. 110-114.

- Joseph A. Massad, Desiring Arabs, University of Chicago Press, 2007. 45.