Words by Yaman Al-Helo

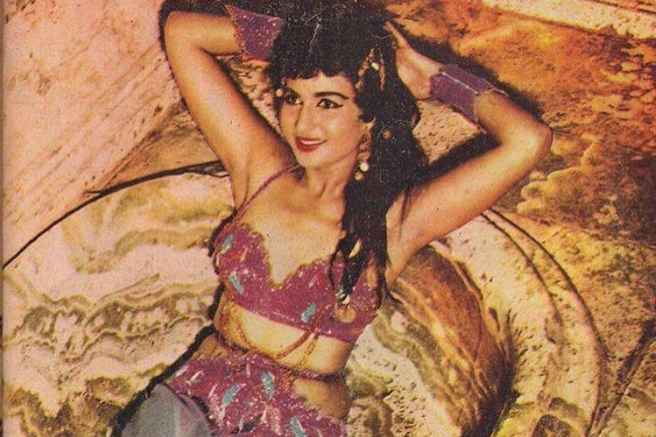

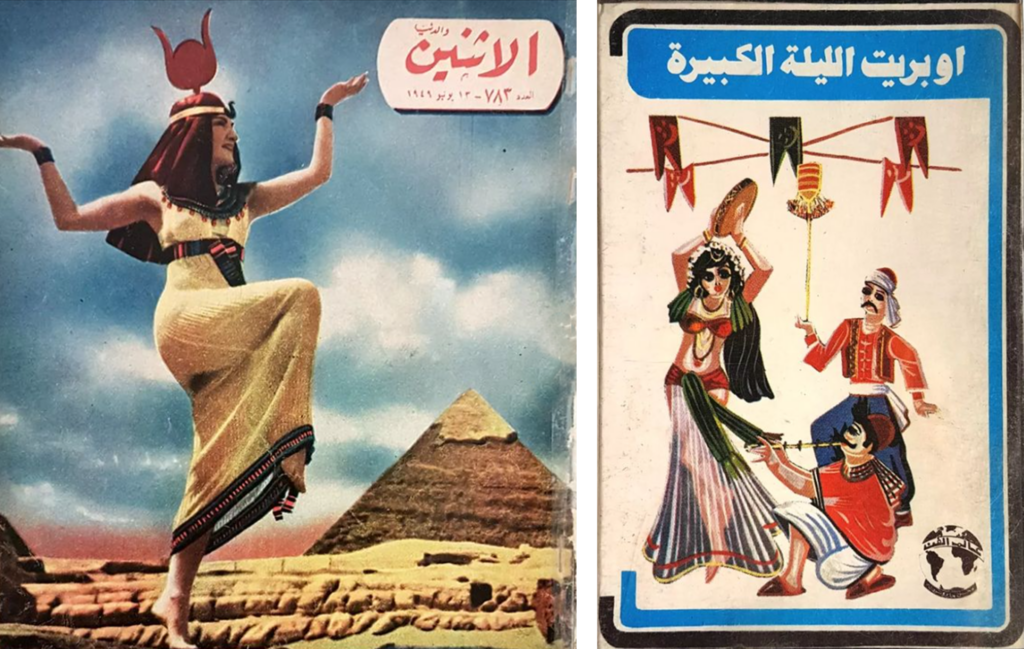

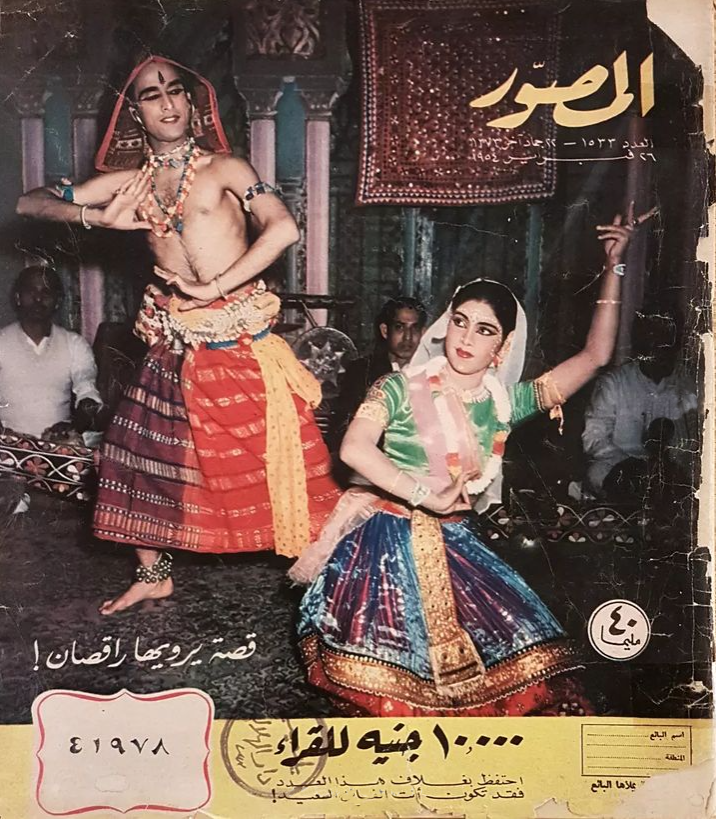

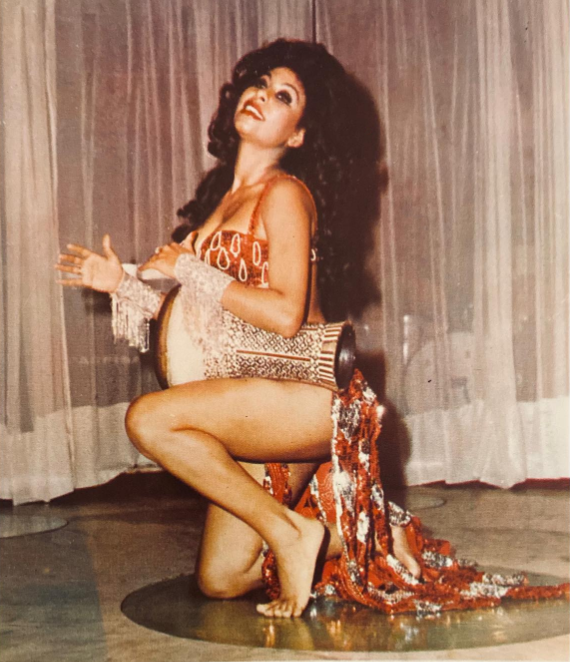

Images from the Cairo Antiques and Dance Archivist archives

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

To whom does the pleasure of oriental dance belong besides men? This question can help us explore the ownership of pleasure in this dance form. In the same context that this assumptive question is asked, some might argue that, apart from men, Western women gain the most pleasure from it.

Long before Western women enjoyed this pleasure, Eastern women were given the freedom to experiment with delicately arranged movements under Islamic authority; gender-separated space served as a fertile ground for this dance to develop into what it is today. Behind closed doors and away from men’s gaze, oriental dance gained its connection with sexuality and temptation.

Long after this dance form took on a sexualized form by Eastern men, and captivated Western men through processes of colonization, it faced further fetishization and sexualization at the hands of Western women. With the twin movements of feminism and sexual emancipation, the figure of the magical nymphs in colorful costumes became not only accepted but celebrated in the sexuality of dance.

The reception of belly dance in Western societies during the 1930s and 1970s points to two contrasting perspectives. In earlier periods, belly dance was often viewed with disdain and as overly sexual, representing an exotic and mysterious “other.” In the later period, there was a shift towards celebrating and appreciating the artistry and cultural richness of belly dance.

It is important to note that, from a Middle Eastern perspective, the distinction between Eastern Europe and Western Europe may be less pronounced, as both are considered part of the “Western world.” But, when we discuss the consumption and perception of belly dance in Europe, it is essential to acknowledge the difference between how it is consumed in different parts of Europe.

Dancers from Western Europe tend to take another path in their careers as oriental dancers, which is largely limited to teaching others and participating in dance groups that present their dances in theaters. But across Eastern Europe, and especially in Russia and Ukraine, it is seen as a prominent art form, and there is a relatively large industry around it, with many dancers and a higher demand for local venues and events. But economic factors also play a role here; many Russian and Ukrainian dancers seek opportunities in Egypt because of its established industry and the potential for higher incomes. Dancers from Russia and Ukraine are heavily represented in Egyptian nightlife.

This is where the examination begins. Below, I tell the story of three fictional characters—Fifi, Shalillah, and Anastasia—whose stories are based on those told during interviews. Each story expands on dancers’ potentially different relation to pleasure through belly dance, and how this is fragmented by class and place of birth. Fifi, an Egyptian dancer based in Cairo who represents local belly dancers working in cabaret, shares the stage with her colleague, Anastasia, who represents the position of dancers from Ukraine and Russia. And Shalillah is a German belly dance teacher, brand owner, choreographer, and the list goes on.

Such comparisons between these hypothetical characters and their stories only look into the specific situation of these performers, professionals, and workers, and the outcomes do not represent the relationship that all people have with this dance form.

Supposing that most paid performers in our current time coming from the West to Egypt identify as cis-women, this limits the analysis to the pleasure of other groups in society with belly dance.

رقصات مش رقصات (Dances… Not Really Dances)

Through choreographies that incorporate Western techniques, someone like Mahmoud Reda in Egypt has attempted to “elevate” this popular form to the level of Western standards of art.

Reda, an Egyptian dance coordinator, is regarded as the father of belly dance performed in the theater. Shalillah, an oriental dancer and teacher who wrote her master’s thesis on psychology and oriental dance and is currently teaching in India, trained with Mahmud Reda and praised his work thoroughly. Fifi Abdou, also the godmother of Fifi the character, held huge respect for people like Reda for spreading oriental dance practices around the world, though she also maintained a critical view of the effect this has on foreign women replacing Egyptian dancers.

Images from the Cairo Antiques archive

Reda, with all his good attributes, is still a “self-exotifier” in many ways. According to Edward Said, such individuals “native” to the origin place of these dances utilize orientalist representations, many of which originated from Western sources, in their embodied and enunciated performances.

The historical context of belly dancing in Egypt reveals the diversity and evolution of the art form. According to Bigad Salama, the 1920s marked the beginning of an evolution that led to the golden years of belly dancing in Cairo during the 1940s and 1950s. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were many types of belly dancers in Egypt, namely the Ghawazi and the Awalem. Though neither style had standard choreography or standard movements that characterized the Reda group in the late 50s, each form was associated with different movements and settings.

Both Ghawazi and Awalem used to perform in public prior to the wave of Islamic fundamentalism that eventually pushed belly dance out of the public space by the 1970s. The two held very different social roles, as the Ghawazi dancers in the Egyptian semi-caste system are (Fala7een) villagers, used to perform in weddings and public celebrations whereas the Awalem dancers performed, mainly during religious festivals known as moulids. In addition to their ability to sing, Awalem dancers were considered less seductive in their movements, and they performed in the city (al-Meden).

During this era, Egypt was part of a diverse empire that witnessed the migration of multiple ethnic groups; its belly dancers were not exclusively ethnic Egyptians but also Roma people in rural Egypt, as well as Armenian, Greek, Jewish, Balkan, and Southern, and Eastern European. While Ghawazi dancers were mostly foreign at that time, today, local dancers like Fifi are more known for their sensual choreography, which is deemed less suitable for public performance and less respectable. And, while local dancers used to dance in the more “respectable” Awalem choreography, now it is foreign dancers based outside of Egypt like Shalillah who have the status of al-Awalem of the past and its association with upscale and professional forms that are appropriate for higher cultural tastes.

Thus, we see that while this dance form has been segmented historically, the groups associated with the “high” and “low” have flipped, impacting both the perceptions of these groups and their relative opportunities. One could draw this reversal to the Reda Troupe of 1959, which received recognition from Western high-art academics. But rather than going to the roots of the dance practice, these academics placed higher artistic significance on the modified, orientalized version of the dance that the Reda brothers developed with the support of Abdel Naser and the Egyptian state. When it toured, drawing on the Awalem credibility, it opened the doors for foreign women like Shalillah to take over these higher-status performance roles.

أسماء مش أسماء (Names… Not Really Names)

“Around the time I started dancing, my friends and I made the then-popular decision to come up with catchy stage names for ourselves,” said Shalillah. The name she chose, however – an ancient Egyptian stage name – raises red flags about the orientalist impulse behind this choice. Such selection has become a common tradition. Until recently, most European and American belly dancers picked names that were romantically suggestive of Arab or Persian culture rather than common names: Zaheret, Chandra, Samisha, Samaweyyah, Chantel, and Mahala.

Selecting these names enhances the fantasy or allure surrounding the dancer’s performance, as they carry connotations that evoke images of harem girls or other archetypal figures often romanticized in pop culture. And, these names seem to add further enchantment to the dancer’s persona, linking them to a sense of history or cultural richness of the imagined ancient form. Lastly, there is also a pragmatic layer: Shalillah said her given German name was too difficult for announcers to pronounce, and that her chosen name was more recognizable in the industry.

Image from the Cairo Antiques archive

Western-sounding names have always been common to use in the industry, though for different reasons. Recently, Slavic-sounding names have become more favorable for work in nightlife, and many “Anastasias” have decided to keep their original names. Egyptian belly dancers have also been pushed to self-identify with cheeky Western names like Fifi, Dina, or Lucy. These names are seen as “sexier” and are thought to draw a crowd, while also helping dancers maintain their personal safety.

Like many other dancers in Egypt, Fifi’s choice of name is driven by the market’s demands in Egypt and the Gulf that have been drawn to Western-influenced elements. This trend extends to pop singers. For instance, pop singers like Alissa (Alissar) and Rouby (Rania) have altered their names that resonate more with audiences. This (re)naming is about more than just names; it reflects a cultural shift where Western traits are seen as stylish or attractive.

أوضاع مش أوضاع (Conditions…Not really Conditions)

Dancers face dramatically different realities in Egypt’s current industry, which can be understood in relation to their access to things that might enhance their opportunities. For example, Anastasia, who comes from a cabaret industry in Ukraine and is currently leading in Egypt’s, has financial capital that enables her to buy better costumes, access plastic surgeons, and secure better contracts than local dancers like Fifi.

Nonetheless, she, like many Russian and Ukrainian dancers, still faces many levels of exploitation as part of their work contracts in Egypt. Anastasia works under a long contract and is continually underpaid by her agency, despite gaining more fame throughout its term. She also faces issues like having her passport taken away and living far from her family, and she has to manage being continually sexualized and faces blackmail to marry and pressure to engage in sex work with someone in the industry. This is a “cost” of being publicly perceived as a talented sex worker. Anastasia additionally faces the risk of being jailed if she doesn’t participate in bribery culture and has issues obtaining legal dance licenses, leaving many foreign dancers with no option but to work illegally.

Shalillah, as an international artist who avoids performing in Egypt, faces a radically different reality: she has a high education about the psychological benefits of “oriental dance” and has some financial privilege in the industry. She participates in festivals, workshops, and weddings and runs her dance academy, which 90% of its participants attend online. And, with the help of her clothing brand that sells dance costumes, she has a higher income than what she would earn in Egypt (on average, 1,000 USD per month).

Anastasia and Shalillah’s financial situations and position within the industry are impacted by the geography of their work. Shalillah enjoys financial security that allows her to remain in Europe, while Anastasia needs to move to Cairo, the center of belly dance for Russian and Ukrainian dancers for the last decade, to have a financially viable career. Here, Anastasia benefits from the low value of the Egyptian pound, allowing her to gain a leg up against local dancers like Fifi; she can pay to get the “goddess” physique now favored within the industry.

Image from the Dance Archivist archive

Customers and club owners often promote certain “physical standards” in cabaret settings: breast implantation has been a popular procedure to do as a dancer in Egypt, and lately, tummy tucks have been on the rise as we see the beautiful rolls that have led the French to call the dance belly dance disappearing.

The pressure to undergo these procedures to stay competitive, either by choice or by being forced by managers, leads to further segmentation between dancers. Shalillah is somewhat protected from such pressure, she is not judged based on the size of her natural breasts, but on her skill set that is at the center of theater or private events.

This fragmented environment—one rooted in geography, financial inequality, and beauty standards—impacts not only how one gains status but also the chance that one can gain pleasure from such practices.

Where does this leave Fifi? Competing against the privileges of competitors like Anastasia, she is alienated from the dance form that originated in her own region. In an industry with multiple realities, ones in Egypt and ones outside of it, Fifi’s biggest inequality is her passport, which limits her to only the Egyptian local dance circuit, where she stands as the second-best option after Anastasia. Unlike Anastasia, who can theoretically leave the industry at any point while maintaining or even expanding her credibility in Europe and elsewhere, the stakes for Fifi are much higher. Fifi is somewhat bound to Egypt, where she learned, performed, and will teach dance. While she may be able to perform elsewhere, she is limited to the same circuit of nightlife performances, and her reputation will follow her.

حلل يا محلل (Analyze your Analysis)

Dancers’ financial gain and social status beyond the dance world may also impact how their perception of their work and what kinds of pleasure they may experience in or because of it. Even looking at a single day, we can see the tapestry of experiences that shape how Fifi, Anastasia, and Shalilleh come to the stage.

THE 15TH OF AUGUST 2023

Shallilah has long-awaited this date, the day of the Yallah Dance festival in Berlin, where she is expected to give an Iraqi dance class for the first time. She wakes up with menstrual cramps, a reminder of the natural rhythm of life, but, undeterred, embarks on her busy schedule leading private dance classes. By lunch, she’s had two falafel wraps and a matcha latte. Despite her discomfort, she conducts her private classes and leads the Iraqi dance workshop as planned. But as the day progresses, she decides to forgo presenting insights gained from her master’s thesis, instead offering to share it over a WhatsApp group. Everyone was understanding, and she called her husband to pick her up.

Anastasia wakes up in Sahel, feeling the weight of a foreign dancer in high demand. A morning joint and glass of orange juice quell the remnants of her vodka-induced hangover. Seeking solace from the heat, she spends the days indoors in conversation with her Ukrainian friend in Germany and her mother, taking brief interludes by the pool. Evening approaches, and Hassan – her manager, friend, substance provider, and sometimes lover – picks her up. She takes the spotlight at a lavish wedding, captivating the audience for hours. The night concludes with a familiar ritual of drinks and camaraderie with Hassan and his other friend. She weaves continuity through her transient lifestyle.

Fifi wakes up to an urgent phone call with Hassan, who is furious that she hasn’t opened the door for a new Anastasia, who had been waiting outside their Cairo apartment. Fifi’s bookings have slowed down since she confronted a disrespectful and handsy customer at the Ali Baba cabaret; the customer went to the club owner, who spread the word that she has an “attitude.” To make ends meet, Fifi has been assisting Hassan in coordinating performances with other dancers in exchange for crashing on his couch and access to his friend. She eventually opens the door to a tall, blond, blue-eyed Anastasia; neither speaks English well, so Anastasia goes to her room to sleep. Later that day, Fifi goes to her friend Dina, another dancer, but upon arriving, finds the door lock broken. Inside, she discovers her friend on the kitchen floor, clearly in a state of distress. Her cousin had tracked her down through an Instagram story, followed her home, and confronted her, causing her to collapse in a state of fear. Both reaffirmed their plan to run away to work in Dubai or Turkey.

***

In examining the diverse experiences of Fifi, Anastasia, and Shallilah, we notice how factors shape their possibility of finding pleasure from belly dance. The 15th of August 2023 serves as a snapshot of their live and how their careers, social status, and personal circumstances intersect with the possibility of pleasure.