Words by: Ahmed Awadalla

Illustrations by: Qaduda

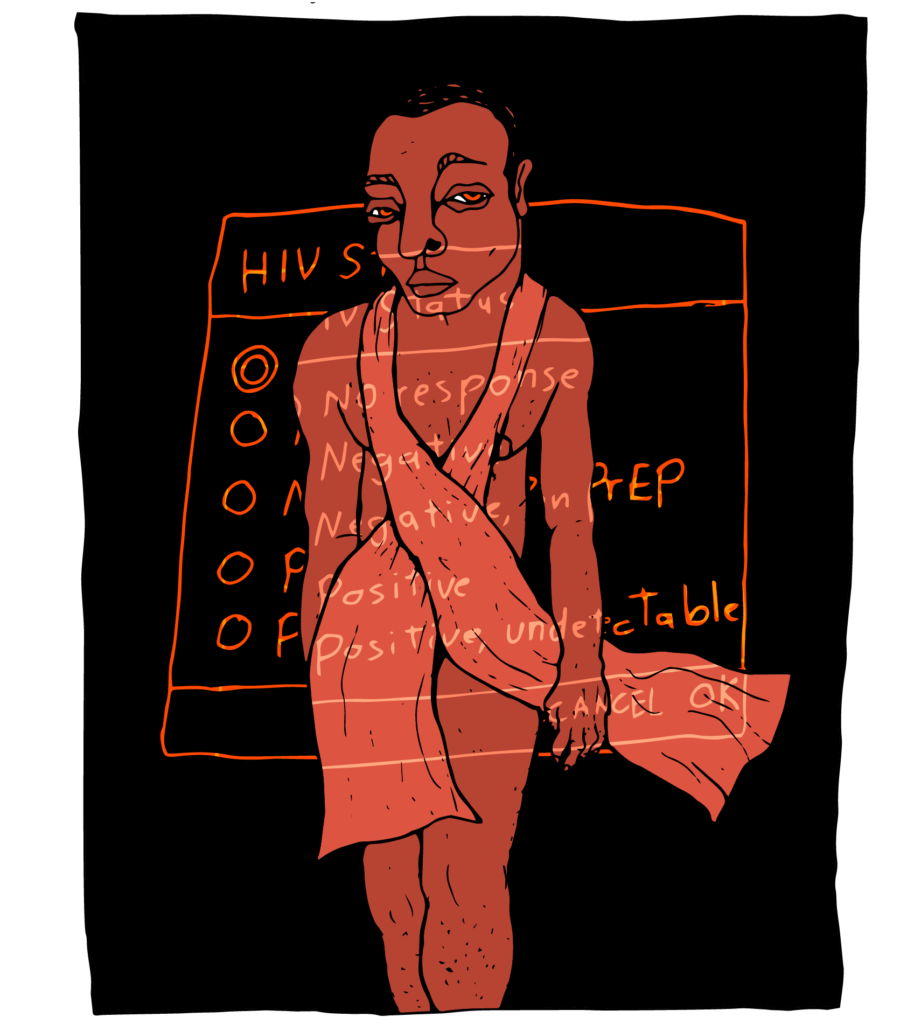

I was lounging on my sofa, flipping through Instagram stories. Vivid images flashed before my eyes – beaches, sunsets, topless men, cat videos – until a story from an acquaintance caught my attention. It was a screenshot of an Instagram story in which a person was accusing another person of infecting him with HIV. Many of the details were camouflaged and there was no way for me to know the backstory, but one thing was clear: somebody was using social media to make claims about another person’s HIV status and the circumstances of the transmission.

Yet, in this bizarre social media moment, something felt very familiar. It was reminiscent of fake profiles on dating apps like Grindr in Egypt, created under the pretext of “warning” other users against having sexual relations with allegedly HIV-positive. Defaming these people using their real pictures, these posts even call on the community to shun them. In some cases, these profiles also include claims that the individual was intentionally spreading the virus.

I believe these statements on social media are an example of how fear of disease clouds our judgment or be weaponized to disgrace enemies, therefore reinforcing stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV.

I started working in the field of sexual health in Egypt in 2008. For my family and many of my circles, it was a deviation from my original career path as a pharmacist. However, this line of work was the core of my passion for health; I have been obsessed with questions of well-being and body function since I was young. Seeking an education in health affairs was about ensuring that people have access to health information and services, especially those on the margins of society. I have no doubt that my queerness shaped that interest; I knew what it was like to be left out and how biased our societal discourse about sex and sexuality was.

But disease panic opens the door to practicing racism and prejudices against marginalized groups, feeding the need to point fingers at and scapegoat others.

Sweeping things under the rug seemed to be the general attitude toward HIV/AIDS in Egypt. People living with HIV could access treatment through government programs, however a comprehensive package of care was lacking, and patients often complained of ill-treatment at the hands of healthcare staff. Moreover, the legal context complicated matters. The criminalization of non-normative sexuality, and sex work, in particular, hindered prevention efforts. For instance, if the police found condoms during a random instance of stop and search, a person could be prosecuted under what is known as debauchery law. The situation in the SWANA region is more or less similar as the multi-layered stigma prevents people living with HIV from speaking openly about their situation, a crucial step in the fight for equal rights.

Illustrations by: Qaduda

In the first training I received on HIV/AIDS, participants were asked to role-play. We were asked to imagine a scenario in which two strangers were about to engage in a sexual relationship, one of them HIV positive and the other negative. We were assigned the role of a friend of the negative person who knew of the other person’s HIV status. The facilitator then threw the question at us: “As a friend, what would you do?” The responses were varied, some said they would immediately inform the HIV-negative person of the other person’s status, while others showed some hesitation about outing someone’s personal information. The facilitator stressed the value of confidentiality and made the point that engaging in safer sex practices must be a mutual responsibility between both partners. The responses were intensely emotional. Many were alarmed by the suggestion of doing nothing about the situation. Others were uncomfortable about how to deal with such a delicate position.

I learned a valuable lesson from this exercise: working on HIV will come with difficult ethical questions. I also learned that the rights of people living with HIV could be infringed upon in the name of protecting others from contracting the virus.

When the virus emerged in the 1980s, governments became concerned with controlling the epidemic. Several measures were introduced to prevent further transmission, including awareness efforts and condom education programs. However, some of the policies that aimed to contain the epidemic were problematic and furthered stigma and discrimination against people living with the virus. One example of such policies was the introduction of travel bans for people living with HIV; according to UNAIDS, 48 countries still have restrictions that include mandatory HIV testing and disclosure as part of requirements for entry, residence, work, and/or study permits. In many countries around the world, including our region, migrants, refugees, and tourists are subject to deportation if they turn out to be HIV positive. Those restrictions, criticized as human rights violations, are based on the dangerous and misleading idea that people on the move spread the virus.Another example is the criminalization of HIV transmission. In 1987, HIV criminalization laws began to appear across the United States. These laws spread around the world with 75 countries with criminal laws that specifically mention HIV. Some versions of the law dictate that people living with HIV have to disclose their status, even if they use condoms or are undetectable. There are several problems with these laws. They lag behind current scientific evidence which states that people living with HIV who receive antiretroviral treatment are no longer infectious. Moreover, they ignore the concept of mutual responsibility and place the burden and blame on the person living with HIV, reinforcing the negative stereotypes about people who live with the virus.

Most of these laws don’t differentiate between intent and negligence. In practice, it is hard to prove how and from whom the virus was transmitted with certainty. This opens the door to false accusations and wrongful judgments, such as the accusations I witnessed on dating apps in Egypt. It’s no wonder that these laws are used disproportionately to target minorities and marginalized groups. In the United States, the black population is not only more impacted by higher HIV rates, but also higher rates of conviction and incarceration in HIV criminalization cases.

This correlation indicates that the fear of disease is not the only motive for criminalization. Clearly, everyone wants to avoid disease. But disease panic opens the door to practicing racism and prejudices against marginalized groups, feeding the need to point fingers at and scapegoat others. This is evident in other cases in which diseases and epidemics have been associated with particular migrant or ethnic minority groups, as we saw with discrimination against groups of Asian descent during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Governments have historically excluded HIV activists from the conversation and decision-making processes, leading to the creation and persistence of these problematic and stigmatizing policies. A large number of rights groups around the world protest such discriminatory laws and lobby for their overhaul.

Illustrations by: Qaduda

I became familiar with this racialized pattern of accusation and criminalization after I moved to Berlin in 2014 to work as a counselor and educator in a sexual health center. There, I encountered narratives of discrimination in intimate relationships and at the state level firsthand. Numerous people came to have an HIV test after a sexual encounter with someone of a minority group, a person of color, a transgender person, or a sex worker. They would reveal their reasoning in their counselling sessions, which were often rooted in stereotypes about these groups; it was their partners’ identity that ignited their concern. These “concerned partners” were similarly more likely to report such incidents to the police, and, the authorities were more likely to condemn partners who belonged to a marginalized group. The most famous case of HIV transmission in Germany involved a celebrity singer in the music band, No Angels, in a highly publicized media spectacle. She was also a woman of color.

These dynamics were particularly clear in a case I managed in Berlin when a client came to seek advice after he contracted HIV from a sexual partner. Their sexual encounters took place before the partner who lives with HIV began his medical treatment. Having felt remorse about not disclosing earlier, he later divulged the secret to the client. When the client arrived at the center, he was outraged, angry, in pain, and wanted to punish his ex-partner. For him, that meant reporting him to the authorities. It was an ethical dilemma. I personally object to the existence of these laws and joined several initiatives that demand they’re overturned. At the same time, I had a duty to respect my client’s choice. I shared with him my principled objection while simultaneously providing information and referral to relevant legal services, should he proceed.

I often think about this case when I see posts defaming a person for their HIV status on social media. I believe that disclosure is the best way forward before engaging in sexual relationships with partners. At the same time, the fear of stigma and rejection stands in the way of open and honest communication. In addition, queer intimacies don’t follow the classical patterns of normative intimacies, which creates situations where communication is not possible, such as casual encounters with strangers. I remember the logo at a Berlin bar that said: share the blame. The burden of communication should not lie on the person living with HIV. It is everyone’s responsibility.

Observing HIV transmission from a transnational perspective between Egypt and Germany, two countries that are different in political and cultural contexts, reveal various forms of discrimination against people living with HIV. The context in Egypt is marked with systemic neglect and denial while in the latter discrimination is codified in the law. Granted, access to HIV treatment and services is well established in global north countries, but HIV transmission laws belie the myth that global north countries have already done the work needed to address HIV prevention.

I focused in this text on HIV transmission as a gateway to discuss how misinformation and bias permeate our attitudes. However, we need to address the different forms of serophobia, which is defined as the fear of, dislike of, or prejudice against people living with HIV. Serophobia manifests itself in acts of violence, shunning, and exclusion which take place at the hands of institutions, family members, or even intimate partners.

We need to create societal discourse and spaces where people can exchange views on these matters in a non-judgmental manner. A free and healthy sexual life means access to information and services for everyone.