Words by Fayrouz

Design by Lina A

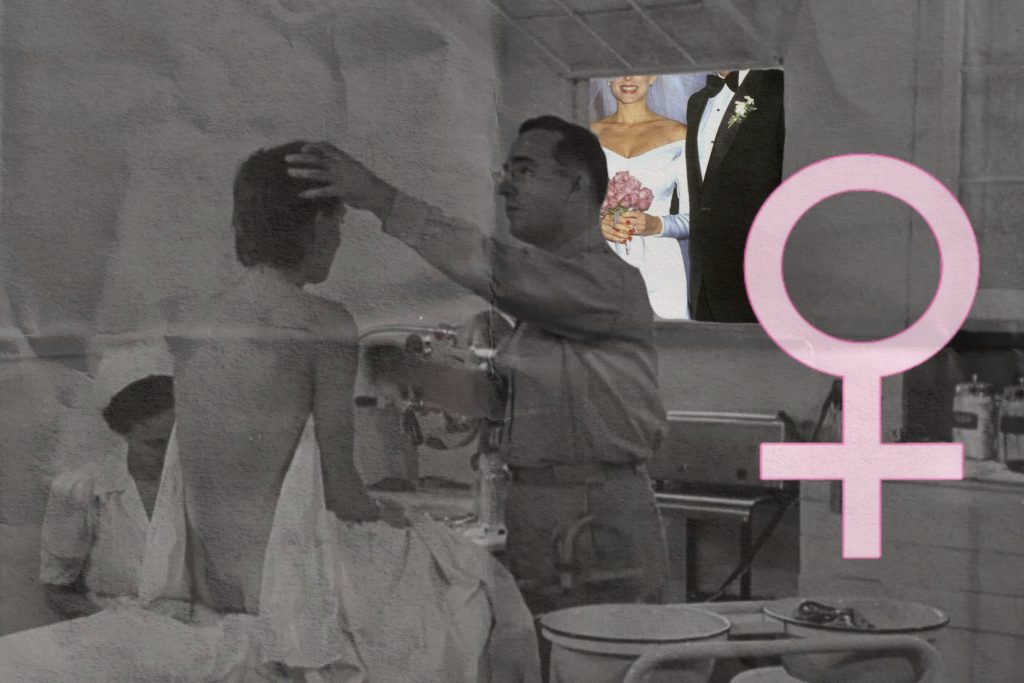

The sexual and reproductive health (SRH) “ecosystem” is made up of multiple institutions, including medical institutions, NGOs, civil society organizations, and medical professionals from varying backgrounds. Though these institutions take a variety of approaches to address healthcare issues related to SRH of women and other disenfranchised groups, they often (re)produce a power imbalance along the axes of oppression that they are trying to counter.

One reason for this is the dominant social and cultural associations of sex, sexuality, and sexual education with taboos or shamefulness. These associations may affect (a) the discursive realm of the SRH ecosystem (how it is spoken about and around, or mobilized in conversations of health and development), by divorcing it from the physiological, physical, and psychological health field and/or other human rights issues, (b) the possibility of inclusive care by medical professionals and practitioners who may not be willing or able to provide resources and services to broad populations, and (c) narrow understandings of and limits on access and just care, and how these materialize (or not) in practice. The discursive and structural issues impact the shape of the SRH system and its precarious position in the medical field, which further perpetuates medical discrimination, particularly against non-normative groups.

My work as a community manager and head of research at a leading SRHR platform in the MENA region and as a research assistant in an NGO focused on youth’s access to SRHR have exposed me to the concerns and needs of everyday citizens from multiple angles. Building on what I have learned about the treatment of two socially-stigmatized groups – women and queer individuals. I will outline some of the gaps between the provided/available services and resources and what they seek, barriers to access, and the implications of these gaps and barriers.

Medical Discrimination, Neglect, and Barriers to Access

Unmarried women seldom have access to sexual and reproductive health services, treatments, and information they require, including proper medical advice devoid of prejudice or microaggressions, contraceptives if they are unmarried, and the availability of resources for issues such as yeast infections, vaginismus, sexual traumas, or issues. Even when women can go to a doctor for check-ups, fear of being shamed about their virginity or lack of understanding about the hymen produce barriers to access; there is a fear that doctors might be able to discern something about their personal lives that the patient doesn’t want to disclose.

Carrying this fear and shame manifests itself both in specific social spheres and in interactions with the medical sphere. Any doctor – gynecologist, SRH medical professional, or otherwise – can discriminate against their female patients. Some doctors belittle women’s pain by implying that whatever the medical concern would resolve when they get married. This was the case for a 23-year-old girl who had hormonal fluctuations and irregular periods, which could be a materialization of so many different health issues that would magically be fixed upon marriage. It was also evident when a 26-year-old who had bronchitis went to a doctor; his first question was “are you married?”. The irrelevance of the question to the overall diagnosis reveals the ways in which societal and heteronormative norms are mobilized against young women and the potential impacts on the level of medical attention they receive.

Women’s marital status becomes central to women seeking medical help. Married women and/or those getting ready to be married are more welcome at gynecologists’ offices to seek services and check-ups. This is not to say that it is still normalized or accepted but it is relatively an easier process if the woman is married. The woman in this case becomes a more worthy service beneficiary than the unmarried woman. Women who are unmarried and seeking care for issues that may signal that they have been sexually active outside of wedlock, invite further judgment or accusations from medical professionals or staff. For example, when women are visiting gynecologists, they are asked, and their medical treatment is influenced by their marital status and a sense of assumed heterosexuality. This heteronormative abjection is normalized through the social and cultural taboos but also draws on the permeance of medical discrimination and the denial of services to women before marriage and to queer individuals. Again, we see medical discrimination in the lack of diagnosis, misdiagnosis, assumptions of hysterics rather than pain in women, and the lack of medications and services for STDs/STIs. While these issues prevail in areas with a general lack of a cohesive and operable medical healthcare system, the way that the SRH system is configured makes it an ever more invasive and life-threatening situation for those marginalized groups.

Queer individuals face similar forms of medical discrimination or lack of care as those discussed above. Queer individuals seeking medical checkups, care, or information about things like STDs and STIs may also encounter potential violence. Some who are “straight-passing” or do not visibly “look queer” may be able to claim they contracted an STD or STI from drugs rather than signaling that they had “non-normative” sexual intercourse, which could seem like a safer alternative.

Through my fieldwork, I saw how common this experience was. Two friends went to the same medical center to get checked for STDs. One was checked by a nurse who was quite helpful. When his friend asked him where to go to get tested, he recommended the same center. His friend, on the other hand, almost got into a fight and was treated poorly. What was different between the two cases was that the former was “straight-passing” so did not raise suspicion about his sexuality, and the latter did not look “straight enough.” This reveals not the failure of community resourcefulness and recommendations, but another case of medical discrimination. This is rooted in individualistic assumptions, judgments, and prejudices so obliterating those requires an appropriate intervention into how ethics can be exercised without resorting to personal definitions of morality or judgment. Interventions within the healthcare system need to address the paternalistic way that this system is configured and then ways to address those altogether.

Of course, status and class also impact the kinds of social pressure and microaggressions that individuals face. Women and queer individuals who are already marginalized and struggle to access healthcare or to conform through “acceptable” behavior socially and culturally can be hit particularly hard by deterrence in SRH settings. Understanding this through an intersectional lens requires us to view how the situation is aggravated when those identities coincide. Less financially capable individuals within such groups are at a much higher risk than those who have the financial capital to go to doctors or to fund their treatments. It is pertinent to understand the discriminatory nature of this situation through an intersectional lens to understand the extent of such social and medical discrimination.

Design by Lina A

Social Silences and (Re)producing Precarity

Social discrimination against both women and queer individuals in SRH institutions is rooted in cultural shame and taboo around reproduction and sexual health, and the impossibility of speaking about these topics in an open or public way. This social discrimination breeds and fosters medical discrimination as it offers a cushioning for such social discrimination to be freely exercised with little to no repercussions or regulations. In areas where there is a lack of formalization within the healthcare system, NGOs usually try to work tangentially to address some of these issues in the forms of awareness campaigns or initiatives.

NGOs often reproduce the silences and moral hierarchies in their own approach to SRH, whether it be in terms of community development or “women’s health,” which can lead to further material consequences for the communities they aim to treat. One example of this is in NGO approaches to “family planning initiatives.” Often sensitized or pink-washed, family planning initiatives are understood as integral to addressing high rates of population growth, overcrowding, rising poverty rates, and regressing social and economic development. For example, when family planning initiatives are introduced as social and economic development campaigns that target reproductive health in rural communities and less fortunate populations (even promoting policies equivalent to the “one-child policy,” at times), they often overlook a major issue these communities face: that people in these areas may not have received a sexual education that addresses the science of reproduction or sex. The nexus between high rates of reproduction, poverty, education, and wealth is also generally overlooked and the normalization of “family planning” without proper grassroots efforts is simply naive.

NGO-centered health initiatives also exclude or draw boundaries around what is “socially acceptable” more actively. “Women’s health” programs play an important role in addressing health conditions from breast cancer awareness to the prevention of female genital mutilation. Though such programming and initiatives are undeniably important, they require health expenditures that can be allocated elsewhere. This allocation could go towards appropriate training of medical professionals and healthcare providers to sensitize their approaches and to delink such bias within medical encounters. This (undeniably) misallocated health expenditure could be allocated for improvements in medical settings, clinics, training, amending school curricula, and addressing the grassroots issues that are repeatedly overlooked and rendered as “sticky issues” that cannot be resolved.

The exclusion of non-normative and marginalized groups is in line with the active social marginalization of queer communities therefore, it does not render generative for efforts to be expended to protect those communities if it doesn’t fit under the guise of family planning.

Because exclusionary assumptions and discriminatory practices are not addressed in these settings, “pragmatic attempts” to address SHR issues end up working within social stigmas and reinscribing the moral hierarchies that already exist. It can also lead to the misallocation of attention or available resources in SRH ecosystems, and inadvertently reproduce inequality in other domains, including harassment, period poverty, marital or relative rape, corrective rape, or violence against women and queer individuals.

Improvisation and Confronting Stigma

Stigmatized communities are faced with medical discrimination and neglect within the SRH ecosystem and are subjected to societal silencing and marginalization. Put in a peculiar position of “fending for themselves,” stigmatized communities use tactics of improvisation to access resources, services, and knowledge. One tactic is to circulate knowledge through informal networks of family and supportive community members, such as information related to remedies, medications, medical advice, and trusted references. Collected through personal experience or another’s visit to a doctor, this knowledge is a crucial way to address deficits in sexual education.

However, when this knowledge is not universally applicable and cannot capture the range of issues around sexual education or health that exist. There is a potential danger that the kinds of information circulated are not specific to the respective individual, which could compound or worsen the issue that it aims to fix. This can result in a cycle of misinformation and misguidance that is formed by and informs a lack of awareness around the complexities of women and queer health. There are potential dangers to sharing this information without the diagnosis or check-up of the doctor for that specific patient and their specific medical issue. Any medical issue or concern does not manifest in the same way so there cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach to such diagnoses. Self-diagnosis then becomes the more readily available option and the easier route for most individuals to resort to. Both forms of diagnosis can ultimately lead to a more dangerous result than facilitate the situation or alleviate the respective concern. One can see the shifting reliance on online and social media sources as an extension of improvisational tactics. Forums such as WebMD or Reddit, and closed groups on social media such as closed Facebook groups have become more accessible. When I was a community manager of one of those platforms, women would comfortably ask about their conditions, ask whether they were pregnant, and what their symptoms could be pointing to, among several other pressing issues. There was always a sense of urgency and worry accompanied by such message requests, which is unfortunate but understandable.

Conclusion

Sexual and reproductive health is often treated as tangential to physiological, physical, and psychological health and there is hardly an integrated approach to addressing SRH within the general health sector. The lack of integrated and holistic approaches; the curation of the SRH system in such a limited, “science-centered” manner that ignores the social, moral, and religious assumptions that underpin it; and the social injustice and discrimination that the system reproduces further highlight how damaging it can be to individuals and non-normative social groups who face discrimination within and outside of the SRH ecosystem.

Many contemporary institutions and social structures that claim to be liberatory end up questioning (and even quelling) the struggle for non-normative existence, well-being, rights, and justice. Examining the inconsistencies and gaps in medical systems and NGOs’ intentions and practices reveals how closely coupled the struggle for existence is with the struggle for medical services and resources. The ongoing lack of communal empathy and regard for the effects of discriminatory and precarious healthcare systems, for the ways that non-normative groups are marginalized, will worsen the social and civil gaps that exist between populations if not interrupted. Addressing issues of access and justice in healthcare and NGO settings is not solely a means to improve the SRHR systems in place. It is also a pathway to countering social inequality by drawing the rights of non-normative groups into the center.