Words by J. D. Harlock

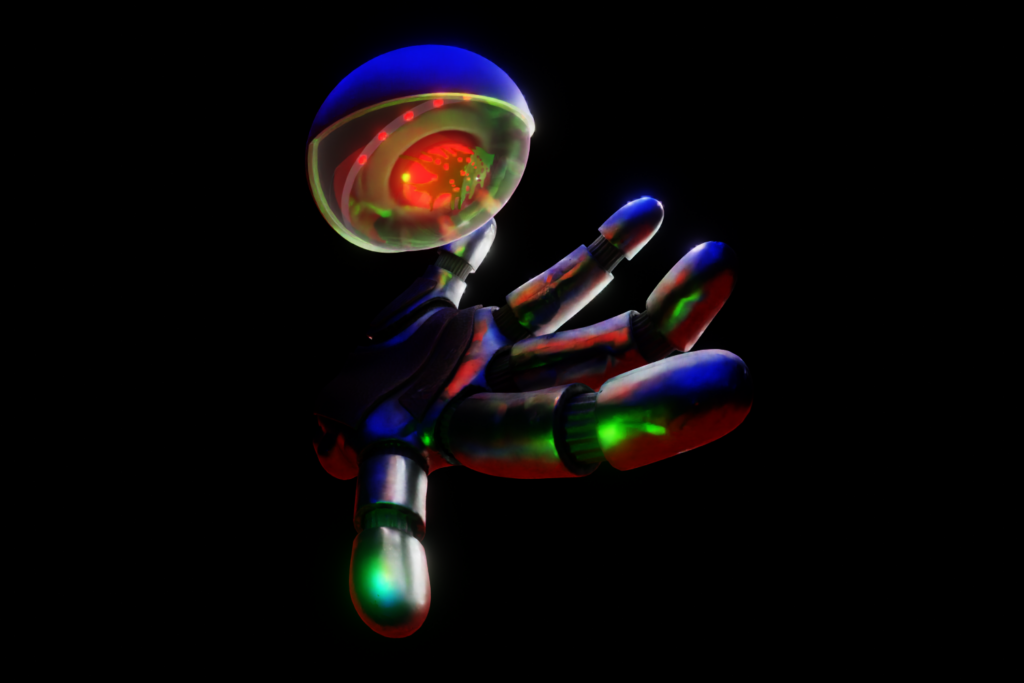

3D visuals by Hescham

This article is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

Growing up in Beirut in the early aughts was as perplexing as it was disorienting. As our elders always reminded us, we were on track to reclaim our coveted title of the “Paris of the Middle East.”

And yet, as the roaring economy under the auspices of Mr. Lebanon1 charged full speed ahead, I couldn’t shake the feeling of an imminent crash. In time, I was not alone in my sentiments. As my peers slowly came to grips with the surrounding reality, many either fled the country at the first chance or drowned their sorrows in a cocktail of drink, drugs, and doomscrolling. Years would pass before our elders realized what we, as a generation, had already accepted.

Regardless, my early revelation should not be attributed to perspicacity or prescience on my part. Big Tech’s techno-utopianism may have indoctrinated the masses, but, by blind fate or fortune, I had been exposed to the reality of low life amid high-tech. Because, as digital entrepreneurs convinced their acolytes that their disruption would help us overcome the problems that humanity was facing, cyberpunk showed me it wouldn’t.

Cyberpunk in the Aughts

What constitutes “real” cyberpunk is hotly debated by aficionados online. Broadly speaking, it is a genre of speculative fiction centered around the transformative effects of computer science (i.e., “cyber”) cast against a radical breakdown of the social order (i.e., “punk”). Cyberpunk had fallen out of favor in the mainstream by the late nineties, as sci-fi aficionados thought its perspective was too pessimistic and predictions too outlandish to be realistic.

Unfortunately, my introduction to this niche science fiction subgenre wasn’t through the zeitgeist, but by being subjected to endless reruns on GCC TV channels. This included the adulterated “adaptation” of I, Robot, essentially a rebranding of an unrelated script slightly edited to cash in on its author’s name recognition. Initially, it invited me in with its aesthetics, but it lacked the storytelling acumen and sociopolitical substance to keep me engaged. I knew something was there, but at the time, I didn’t have the means to delve deeper.

Although Lebanon was infamous for having one of the slowest bandwidth speeds in the world, by the end of the aughts, we could finally afford to forgo dial-up in favor of a broadband connection. This upgrade provided me with unfiltered access to the information highway. For the first time, I could explore all forms of art, entertainment, and media at full throttle, free from the socioeconomic and financial constraints that previously prevented me from possessing this critical material.

Cyber City Beirut

From the Anglosphere, I was exposed to live-action films like Strange Days, video games like System Shock 2, and comics like Transmetropolitan. From Japan, I was exposed to manga like AKIRA, anime series like Texhnolyze, OVAs like Macron Plus, and feature-length productions like Ghost in the Shell. Whereas the works from the Anglosphere tackled complex sociopolitical and economic themes that informed my views on race, gender, sex, and economics, what I could unearth from Japan grappled with existential themes in a cerebral way that forever changed my perception of the human condition.

In hindsight, these works catalyzed my overall progressive views on LGTBQI+ rights, social security, universal healthcare, free education, environmentalism, universal basic income (UBI), and decriminalizing drugs and sex work. Just as my father instructed me to be cautious of our law enforcement agents in an occupied Lebanon,2 Judge Dredd opened my eyes to the threat of an increasingly militarized police force posed to the Lebanese long before the 17 October Revolution was thwarted. Just as my mother warned me against the ills of the internet, Serial Experiment Lain showed me the social isolation a World Wide Web would ensnare us in.

Then it finally hit me: Beirut is in every way a prototypical cyberpunk setting—a city distorted by its obsession with its own techno-optimism that blinded us to our imminent collapse.

Cyberpunk didn’t just inform my views, however; it also catalyzed my questioning of the false narratives being sold to us by the political elite through our impressionable parents, who, despite having good intentions, didn’t realize it was all a lie. In addition to appreciating the genre, I couldn’t help but notice that the contrast of high-tech against social decay was uncannily similar to what I was experiencing around me.

As algorithms hailed in ride-shares that drove us to dates at international restaurants all over the city, kafala – a codified system of modern slavery – allowed employers to trap their domestic workers indoors. While the figurehead of the political oligarchy called out critics of “early marriage” in a tirade against same-sex civil unions, a careless leak exposed us to a state-sponsored hacking operation wherein our spies stole our passwords and pried into our communications.

Even though I had reservations about these tech-driven initiatives, I was still blindsided by how catastrophically technological advancement had accelerated Beirut’s collision with reality. And then it finally hit me: Beirut is in every way a prototypical cyberpunk setting—a city distorted by its obsession with its own techno-optimism that blinded us to our imminent collapse.

Every proposal by the technocrats – a term drilled into our heads – was celebrated as a step in the right direction, and then shortly forgotten as the future it guaranteed moved farther out of reach. Few, if any, of us were concerned that project after project – each pledging to turn our city first into “the old Paris,” then into “the modern Switzerland,” and, eventually, “the next Silicon Valley” – had folded before our eyes as the state piled up more and more debt to cover the bills these ambitious projects racked up.

After promising us that these projects would bring tourists, then deposits, and then, by my generation, seed funding, a tech hub christened Beirut Digital District (BDD) was established right next to the reconstructed downtown, Mr. Beirut’s infamous major urban development policy failure. Through BDD, the politicians took the public’s money to fund their friends’ and families’ dead-end startups. By the time CNN’s Andrew Stevens lauded BDD as the powerhouse for startups in the Middle East, we’d already seen the post-Civil War elite squander any and all investment in our country through a toxic mix of incompetence and corruption.

At the same time, technological developments from the West and Far East that once would’ve taken years, if not decades, to reach a small Levantine nation were now available in physical and virtual marketplaces as soon as they launched. From gaming consoles to app stores, year after year, the lag in releases between us and our relatives slaving away in the GCC continued to narrow.

3D visual by Hescham

Future Shock Syndrome

As one establishment failed us, another swerved in. By then, it was clear to me that the flashing lights of the hype cycle were just another false front for another agenda that never had our interests in mind. The world I was living in wasn’t just moving too fast; it was heading in the wrong direction.

Although growing up, my “radical” views contrasted with those that dominated the conservative environments I was forced into, it was inevitable that others my age grew partial to discussing “taboo” subjects once exposed to new ideas in our college years. This pattern was the same for our parents and their parents, too. However, across age groups and sects in Lebanon during this period, there was an overwhelming anxiety about where these progressive trends were leading. Ironically, this distracted many from the real problems facing Lebanon, in terms of the liquidity crisis and ever-inflating debt from warlords looting the people left and right and in terms of the domestic security crisis created by armed militia.

Others, however, were experiencing “future shock,”3 a psychological state in which we perceive “too much change in too short a period of time” to the extent that it scares us to a halt. If not for my embrace of cyberpunk art, these same fears would’ve paralyzed me — I had braced myself for the impending impact. Unfortunately, predicting the future doesn’t mean you can stop it. Though I was psychologically prepared, there was little I could do to prevent the fallout from the successive crises in Lebanon on my family.

The Shape of Things to Come

Recently, I’ve been revisiting the cyberpunk art, entertainment, and media I grew up with renewed insight. I now realize that it wasn’t just flights of fancy running on the rule of cool, but a prescient warning and worldly preparation from the West and East for the future that awaited Lebanon and, in time, all of us.

And, I’m not alone. In the last couple of years, speculative fiction has finally been embraced by the mainstream. Of course, this unprecedented embrace follows the high-speed technological destabilization we’ve been experiencing collectively in modern times. What we once thought existed squarely within the imaginations of the sci-fi fandom has become a reality. And, for better or worse, there’s much more of it down the road.

With TV Shows in the vein of Black Mirror and video games like Cyberpunk 2077 developing massive fanbases, cyberpunk, in particular, has experienced an unexpected resurgence because of how its ‘preposterous’ prognoses have come to fruition. It is a screen into our futures, offering us a means to cope with technological change while shaping our feelings toward it.

But this process is never balanced. Just as I came to terms with this before many in my generation, and they before many of their elders, the Lebanese and the rest of the middle economies in the Global South will have experienced the full realization of the cyberpunk nightmare before it reaches the “developed” world.

Because the future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.

- “Mr. Lebanon” is the Western media apparatus’ affectionate nickname for the Saudi-backed Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri (1992-98, 2000-2004).

- The “State” of Israel’s occupation of Southern Lebanon lasted for around eighteen years, from the start of the Israeli invasion on the 6th of June 1982 till the Israeli withdrawal on 25 May 2000. The Syrian Arab “Republic’s” occupation of Lebanon lasted even longer, beginning with the Syrian intervention in the Lebanese Civil War on the 31st of May 1976 until April 30, 2005 following intense international pressure and the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri.

- Future Shock was a term coined by American futurist Alvin Toffler in his 1970 book of the same name, defining it as a certain psychological state of individuals and entire societies.