Words and Images by Yasmin Tams

This article is part of the “Sana Wara Sana” issue

Growing up in the old city of Jerusalem, there weren’t any medical facilities due to the occupation. Like many resourceful Arab mothers, my mother was familiar with alternative remedies and would start by treating us at home. When my brother and father got sick, I would go with her to the attar to gather ingredients to create our own remedies until we could seek further medical treatment, if needed.

20 years later, at the peak of Covid, I watched people all over the world try to (re)cultivate their indigenous wisdom of remedies, trying to combat the illness in any way possible. But with no luck. In Palestine, most of this wisdom was transmitted orally – no written documentation, much lost to time. We suffer from what I call the “hakawati effect,” where we pass stories through word of mouth. While this form of transmission was effective in previous generations, the word often died with the last practitioner. Furthermore, each village and family genealogy has their own twist on these remedies, each daughter putting her own spin on it. No two are the same.

Following trends of globalization, many millennials and Gen Z lost touch with their Arabic and Palestinian roots – they were deemed secondary in Western standards. This created a generational gap in the collective wisdom, where older generations like Gen X carry on this wisdom, but younger people are out of the loop. In a culture that documents orally, the loss that we face as a culture is great.

In recent years, as people continue to raise awareness about Israeli attempts to erase Palestinian tradition and heritage, the younger generation has started to reconcile with their heritage and attempt to rekindle lost information. As a designer, I felt it as a duty to contribute to this effort, not only by documenting that heritage, but also by facilitating the access to that wisdom.

The complexity of transmission

Many local Palestinian remedies come from herbs local to our villages and cities. So, the north, south, and central each have their own remedies for the same illness, with key ingredients like olive oil shared across them. These remedies take root and transform organically. Perhaps the remedy was passed down through the family, or heard that it worked from someone else, or it was an experiment. This local variance adds a layer of complexity in documenting the subject.

These remedies and techniques are not typically considered part of our Palestinian heritage, and perhaps not protected, preserved, or mapped with the same rigor. Still, they remain out of necessity, for example, when Western medicine isn’t accessible due to the occupation, or when treatments or medications are not available. They are a way to treat oneself, to find relief from common ailments.

These are not simply “placebos,” nor are they separated from Western medicine practices in Palestine. Rather, this is part of the holistic treatment prescribed by doctors across the region. These local herbs are seen as part of Western medicine, as we know it. For example, doctors often tell patients to drink or incorporate alongside modern medicine to achieve the best results, from curing stomach aches with miramiyeh to drinking chamomile for dry coughs.

Designing products for self-administration and comfort

My project came to focus on three techniques used to treat the most common of winter illnesses. I wanted to create products that allowed for easier administration, for young adults and adults who are living alone and far away from our traditions and culture. These products are meant to be a vessel of connection, which reminds the users of their mothers’ warmth and presence in a time when she is needed most. They also incorporate a series of design elements, stories, and amulets that preserve cultural traditions.

Compress

When I was sick with a cough, my mother would bring large cotton sheets, lathering them with lukewarm olive oil that she heated prior and placing them on my chest. She’d ask me to put my pajamas on top and would tuck me in, praying over my head in hope that I would sleep and feel better when I awoke the next day. When she removed the compress, she rubbed the remaining olive oil into my chest. The logic was that the olive oil was a lubricant to the lungs that would soften them, so the cough was less dry and hard.

This inspired the first product: a compress made of natural wool fibers, which would maximize the amount of oil that was transferred to the desired area. It can be worn as a necklace, fastened around the neck and able to be adjusted to the appropriate length. I incorporated tatreez motifs of an olive branch as an ode to my mother, and a written amulet that is often told to those who are sick: b3eed il shar 3ank (tr. may evil be far from you).

Therapeutic Cup

Like a collective memory, it seems that every Arab remembers their mother making them an herbal tea for their sickness, with specific herbs being used to cure each illness. In fact, they are used so often that some people even say they can no longer drink a specific herb without being reminded of being sick. Inhaling steam is another common remedy, which is believed to help unclogging and clearing out the nostrils and sinuses.

This product brings these two important treatments together. Initially, I designed a cup with a strainer, as many teas and blends are loose-leaf. When I created the prototypes, I realized that the steam from the tea as it’s brewing could also be wafted toward the face, acting as a mini inhalation system.

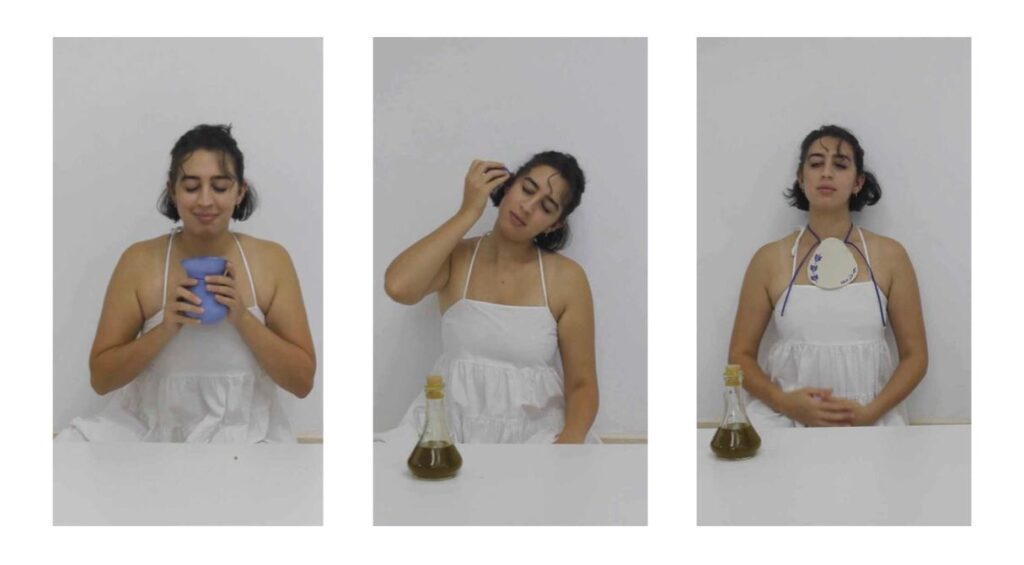

Darina Jabr demonstrating how to use, from left to right, the therapeutic cup, liquid dropper, and compress.

Full video here.

It contains two ceramic parts – the cup and a stackable strainer. The shape of the strainer is an elevated teardrop, allowing the localization of steam toward the face of the user. The holes of the strainer are arranged in a Palestinian tatreez motif for a flower, symbolizing the herbal blends that should be used. The inner rim is engraved with another spoken amulet that mothers tell their children when they’re ill: yrou7 il shar 3anak (tr. may the evil leave you). And finally, the mug is molded as a hug mug, which allows the user to warm their body as they wrap their hands around it.

Liquid Dropper

Middle ear infections are one of the most common winter illnesses. From a young age, I remember my mother heating some olive oil and attempting to drop it into my ear to ease the pain. But it often got everywhere before entering the ear canal, leaving a mess in its wake.

I never found a product to aid the struggle of its administration, so I designed this dropper. It helps with each step of the process: it allows you to measure the amount of olive oil or liquid needed (too much can be quite dangerous), it can be heated, and its curved shape and spout make it more comfortable to pour the liquid into one’s own ears. The dropper is also inscribed with a spoken amulet, ma tshouf shar (tr. may you never see evil).

From left to right: liquid dropper, compress, and therapeutic cup.

Preserving the whispers of generational wisdom

This heritage seems to be vanishing rapidly, forgotten, with people either unable to retrieve such information or disregarding them as “unsafe” or ineffective. However, when Covid struck, and then the war, shortages of medicine forced people to recall and remember this multi-generational form of wisdom that remained as whispers in the back of their minds.

Like all elements of our heritage, keeping this wisdom safe is important. As Palestinians, I think it’s a duty to take these remedies seriously; the rich blend of knowledge they embody remains relevant across generations. And yet, these remedies are often overlooked in our collective project of preservation, perhaps deemed too intangible to prioritize. We need to push back on this, to work to document all forms of heritage, tangible and intangible, so they are not erased or forgotten in “modern life.” They hold a significant place in our tradition and everyday lives.

This is more pressing as we consider how knowledge is transferred between generations today. These products are a physical way for the current young generations, who might lack the presence of their mothers and grandmothers to guide them when they’re sick, to carry on these practices. These functional tools are vessels of wisdom, bridging the past and present to ensure that these traditions remain alive and accessible into the future. They not only preserve the practice of Palestinian folk remedies, but, by facilitating self administration, they also empower younger generations to reclaim these practices and integrate them into their daily lives.