Interview by Noor Sleiman

Photography by Asma Hamdi

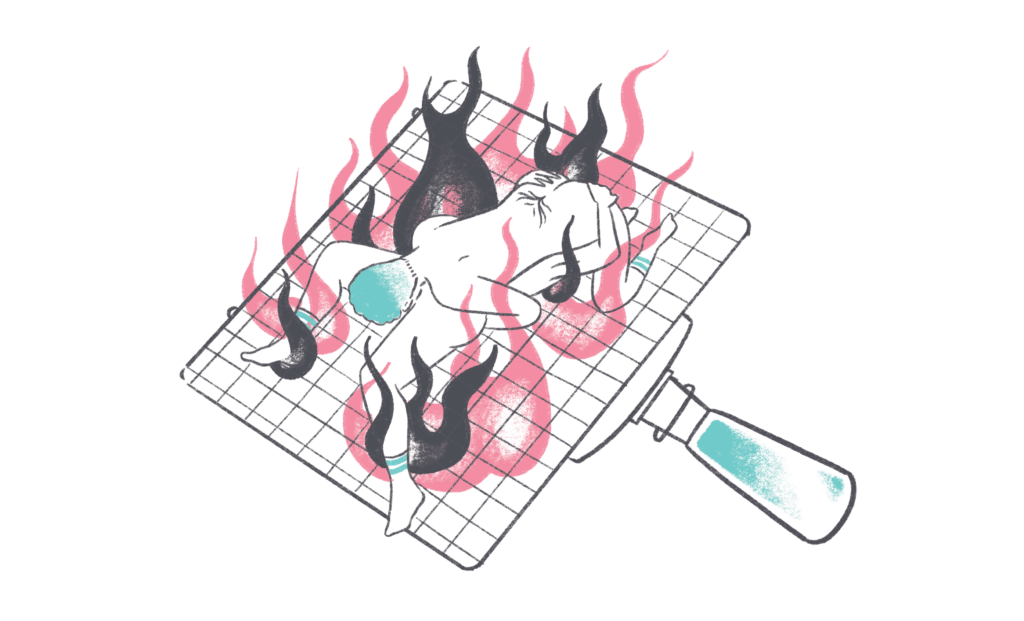

Artwork courtesy of AL Saqi – Illustrations by Haitham Haddad

Translation by Hiba Moustafa

This interview is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

What do words like “bicycle” in Egypt, “grill rack” in Tunis and “pigeon-keeper” in the Gulf mean? What if we dismantled language’s brutality and tried to understand its historical context? How does language intersect with identity? How do we talk to and about ourselves in our own languages?

These are questions that graphic designer Marwan Kaabour dared to ask and tried to answer from a queer perspective by compiling and documenting 330 terms in a single queer Arabic glossary. Kaabour conceived of The Queer Arab Glossary as he was working on Takweer, an Instagram page he launched in 2019 to document and archive Arabic queer culture by researching the archive of Arabic cinema, TV, theater, politics and popular culture.

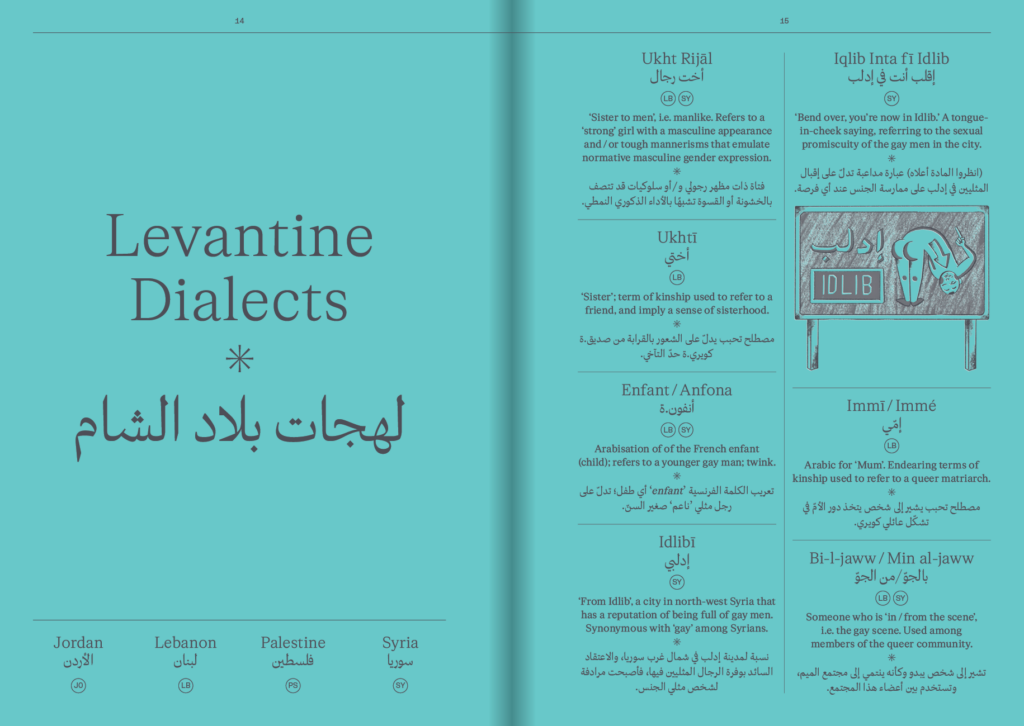

Released in June 2024 – Pride Month – by Saqi Books in London, The Glossary is made up of six sections divided by dialects from the Arabic-speaking region – Levantine, Iraqi, Gulf, Egyptian, Sudanese, and Maghrebi – and each term is accompanied by an explanation and its historical context. The text is complemented by commentaries by eight writers and artists, who share their experiences and readings – including writer Rana Issa, singer and musician Hamed Sinno, poet and associate professor Mejdulene Shomali and writer and director Abdellah Taïa – and is illustrated by Palestinian graphic designer, Haitham Haddad.

In one of Badaro Street’s cafés in Beirut, with so much passion and spontaneity, Kaabour spoke about his experience compiling The Glossary, its goal, and the contradictions he chose to play on, namely that it documents terms that are often used within the context of incitement and hate speech against LGBTQ+ community. In addition, this conversation addresses concerns that some in the LGBTQ+community have about the release of The Glossary amidst the unprecedented genocide that Israel is carrying out against Palestinian people, and how this might further their project of pinkwashing as a way to justify the erasure of Arab and Palestinian identity and memory, and our peoples’ history, art and experiences.

“I wanted to draw a queer linguistic map of the region for us and about us”

How did Takweer play a role in the creation of The Glossary? And who is the target audience?

The Glossary is Takweer’s first project. Takweer has thousands of followers [on Instagram], mainly from the Arabic-speaking world, and I’d seen them using queer terms that I had no idea what they meant. My interest was piqued. I wanted to learn more about queer language and terms, how they differed from one Arabic-speaking region to another, and to understand their historical and linguistic contexts.

I started compiling these terms, asking my followers to send them in without the need for them to be scientific, academic, or politically correct, but rather colloquial and popular. I thought that they would be up to 60, but I received hundreds of them over four years. I decided to draw a queer visual map of our Arabic-speaking region that documents how we talk and the terms we use, negative or positive, and publish them in a book “for us and about us.”

As for the target audience, it’s Takweer’s Arabic-speaking queer followers, anyone who shares their cultural interests, and Arabs and non-Arabs who are interested in queer narratives, including researchers, historians, and writers.

Though it’s a queer Arabic glossary, the introduction, and articles are in English only, while the definitions of terms are in both Arabic and English. Why is this?

I decided to publish the book in English when a bilingual version wasn’t a viable option – I’d wanted it to be. Several publishers told me that bilingual books aren’t popular, and when I suggested having split Arabic and English versions, I was told that distributors in the region wouldn’t be interested. This is why the book ended up having its current form.

This does not mean, however, that the introduction and articles aren’t important. They add political, historical, and cultural dimensions to it, for each contribution has their unique experiences and expertise in different areas. They enrich the glossary. For example, in his article, Adam Haj Yahia explains how the Israeli occupation forces have historically used the criminalization of Palestinian sexuality to justify violence and deliberate imprisonment of Palestinians. And today, they claim that they protect LGBTQ+ people and care about our rights more than our own families.

Illustration by Haitham Haddad

“Here: A History of Harm”

Did you have any doubts or concerns about the reaction of the LGBTQ+ community itself while working on The Glossary?

I want to clarify that the book doesn’t include the secret terms that queer people usually use among themselves, but rather the ones that we use publically in our everyday conversations. So I had no scruples about the project. Basically, it acts as a translation of my interest in language and the linguistic atmosphere of queerness in the Arabic-speaking world and the historical cultural factors that played a role in the creation and usage of certain terms. My goal was to delve into these contexts, publish them and put them into the hands of the readers so they can form an opinion about them.

My intention is no to diminish the harmful impact of these words or the fact that they’re used to insult, oppress, and marginalize us. On the contrary, I’m saying, “Here’s the history of harm and its context.” Harm is a part of our history in the region, and if I overlooked negative words, I’d have offered half-truths. So I decided to tell the whole story and left it for them to decide.

Personally, during the research process, I became more curious about language, how I understand and interact with it as a queer person. I felt like some of the negative or harmful terms that I documented have lost some of their toxicity, as if I was able to dismantle the “scarecrow” standing behind them.

Can you say more about how terms used by heterosexuals as slurs against queer people were taken up to create a queer glossary?

I think it’s strange that we find it easier to use Western or Arabicized words, as if they were the only correct language to express our identities, personalities, and sexualities. Meanwhile, we reject the language that was born in our own societies. I’m not saying that all words are correct, nice, or politically correct, but we even reject the ones used jokingly among queer people because the context, tone, and relationship with the other person affect how a certain word is perceived. We have the right to do that, to control our colloquial language, how we use and judge it.

Photography by Asma Hamdi

My intention is no to diminish the harmful impact of these words or the fact that they’re used to insult, oppress, and marginalize us. On the contrary, I’m saying, “Here’s the history of harm and its context.” Harm is a part of our history in the region, and if I overlooked negative words, I’d have offered half-truths. So I decided to tell the whole story and left it for them to decide.

“Let’s document our stories and make them a part of history”

Lebanon, as is the case in many Arabic-speaking countries, has witnessed anti-LGBTQ campaigns under the pretext that homosexuality is “imported from the West.” How did you refute this through The Glossary?

I hope that The Glossary will be able to refute such arguments on two levels. First, by proving that we’ve been here since the beginning of language. We’ve been using our language to tell our sweet, bitter, happy, and sad stories, particularly that The Glossary includes words with very ancient origins. Second, it does so by addressing the West that claims we’re all born patriarchal homophobes who can neither accept others nor fight for their rights.

It’s an attempt to tell the West that its views of us are very superficial, for our realities and truth are far much more complex and profound.

This conversation addresses concerns that some in the LGBTQ+community have about the release of The Glossary amidst the unprecedented genocide that Israel is carrying out against Palestinian people, and how this might further their project of pinkwashing as a way to justify the erasure of Arab and Palestinian identity and memory, and our peoples’ history, art and experiences.

Photography by Asma Hamdi

You dedicated The Glossary to Palestine, which has been targeted by the most heinous and brutal genocide for the past 10 months. The Occupation often uses pinkwashing to justify its crimes and demonize the Palestinian society. Because The Glossary contains terms that are used in hate speech against LGBTQ+ community, did you fear that it might be used in such a context?

I think understanding the political context and purpose of The Glossary can provide an answer to this question. The Glossary, explicitly and clearly, is based on a progressive, leftist, and feminist thought that speaks about and supports Palestine, addressing the genocide and the right to resistance. This acts as evidence that these principles lie at the heart of our activity, myself and all the contributors. I think this will block the way for anyone who may try to misuse it.

What is happening in Gaza is an act of erasure, not only of people but also of its history, environment, and culture. This erasure allows the occupation to control the Palestinian people’s story, now and in the future. That’s why we must document our stories to preserve them and make them part of history against the occupation’s will. I tried to do this through The Glossary, especially that queer stories haven’t always been at the heart of the popular story, but rather marginalized.

“Stirring the imagination”

Palestinian graphic designer Haitham Haddad did the accompanying illustrations. They look aesthetic in a way that could be seen as softening the harsh and humiliating tone of these terms. Was this a goal? What was the message behind them?

We tried to evoke the complexities and contradictions contained in the words, how we interact with and imagine them. For example, “dūdakī” دودَكي – that is used in the Gulf meaning “riddled with worms,” in reference to the wrong belief that homosexual men have all kinds of diseases – was accompanied by an illustration of a person wearing jewelry made of worms. It was an attempt to bring queer myths or the heroes and villains of our stories closer to the reader’s imagination and to challenge hate speech, as if to declare, “Here I am, celebrating myself and who I am. Despite everything you say about me.”

Illustration by Haitham Haddad

What are your favorite terms and why?

My favorite terms are the ones that surprised me when I learned their origin and history, including:

| Ṭubjī – طُبْجي | It’s of Turkish origin, with “ṭub” meaning artillery and “ji” meaning the owner of something or the profession of someone. It means artilleryman. It’s a slur to refer to any person (usually a man) who has homosexual sex. |

| Ṣaf’ūn – صَفْعون | It’s of Gulf origin, and is used by homosexual men to refer to someone they find sexy or attractive. It’s said to date back to the time of Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir bi’Llāh who had people in his court who were paid to be slapped at the back of their necks by the caliph or princes. They were called Ṣafa’na. |

| Shakar – شَكَرْ | It’s a derogatory word that’s used to describe anyone who has both feminine and masculine characteristics, who is gender-fluid or nonbinary whether they’re transgender, homosexual or intersex person. It is typically said like this, “shakar bakar,” s/he is neither a man nor a woman” that refer to people who are gender-fluid. It may have become known (at least partly) when it appeared in a song by the popular Syrian-Lebanese singer, George Wassouf. It may also be used jokingly among queer people. |

| Shawwāya – شَواية | It means a “grill rack” and refers to versatile gay men who flip during sex, assuming both top and bottom roles – “like meat on a grill.” |

How do you wish everyone who reads the book feels?

Curious, surprised, their imagination stirred and to form a clearer and more realistic idea about the realities of queer people in the Arabic-speaking world and their struggles.