Words by Tazir

Translated by Hiba Moustafa

Artworks by Samar Zureik

This article is a supplement within the “Frenquencies” issue

In a group of Arabic-speaking queers, only Libyans understood what ti hirkun, alzawz falawl dibyu kambiu wabietali taleu qardasha meant. It was a starting point for a conversation on the different queer languages in their countries. This is not Arabic, but the encrypted queer language in Libya. This conversation pushed me to examine further the peculiarities of these languages, the environments from which they emerge, and their relationship to the queer struggle, in general.

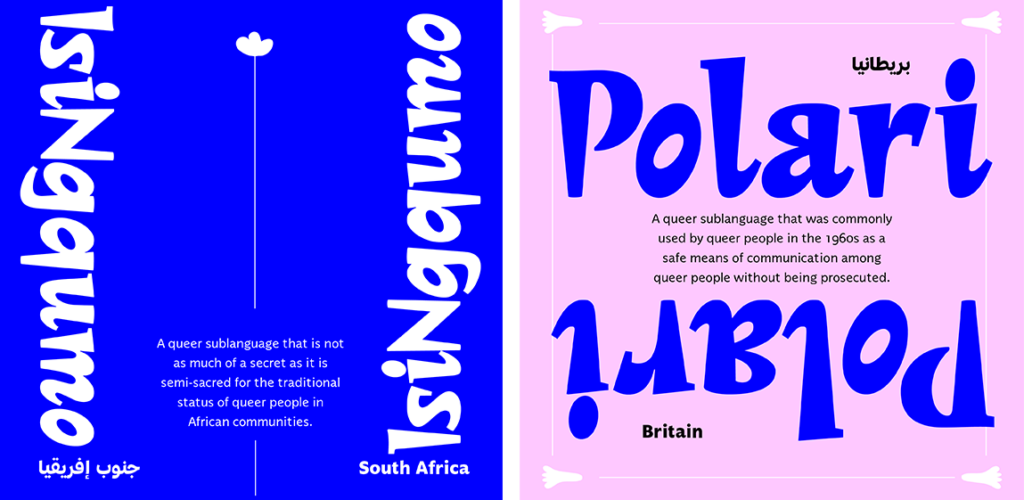

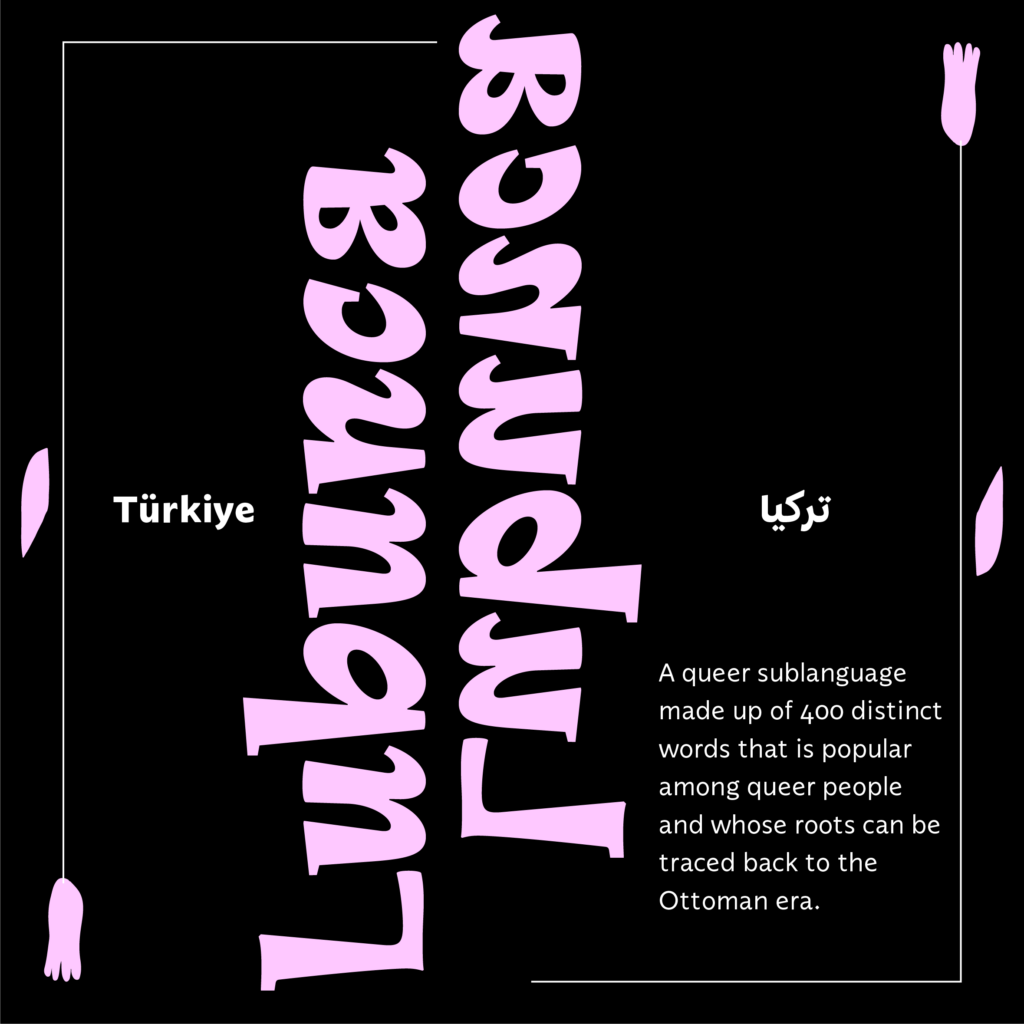

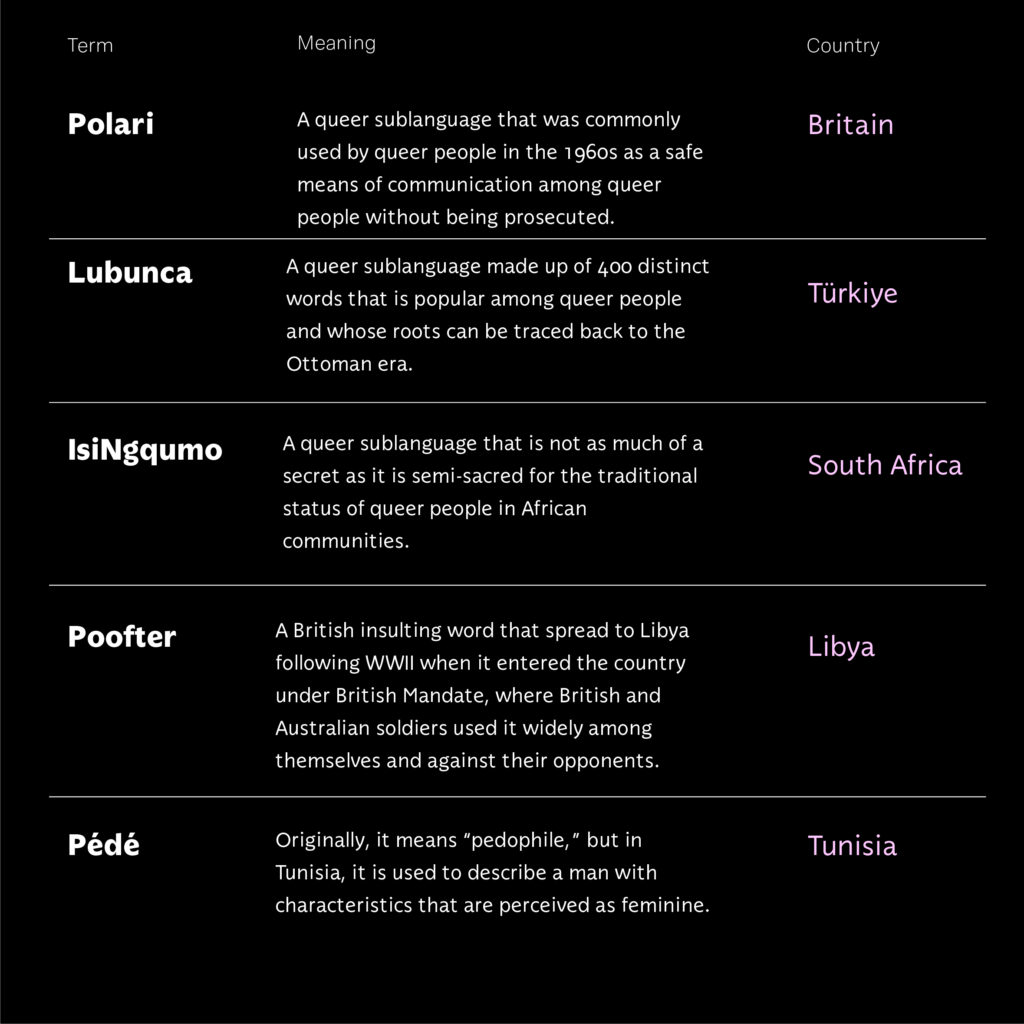

Usually, these sublanguages arise from terms specific to queer groups, and then evolve over time to form a lexicon or language that is distinct from the one used and spoken in society.1 This phenomenon is common in several communities all over the world. Polari was used by queer people in Britain in the 1960s as a safe means of communication among queer people without being prosecuted. Lubunca too, which is made up of 400 distinct words, is a popular language among queer people in Türkiye, its roots tracing back to the Ottoman era. IsiNgqumo is a queer language used in South Africa, but it is not about secrecy as it is about its semi-sacredness for the traditional status of queer people in African communities.

Queer sublanguages vary in size and inclusiveness from one community to another. Some communities might only have secret words and adjectives, while others may have their own highly complex lexicons. This variety shouldn’t dissuade us from studying this phenomenon and looking into the cause(s) of their richness and limitations, as both reflect the structure and history of queerness in a given society. And, despite the differences in cultures and the distance between the societies in which they appear, these lexicons are the result of similar social and political factors: social oppression, closed-mindedness, the need for creativity,2 and other factors inevitably led to the emergence of a clever secret special language.

العمل الفني: سمر زريق

These languages consist of variations or combinations of commonly spoken words – queer people have made up a friendly or safe language from one that is often hostile to them, drawing on permutation, alteration, formation, and shifting the connotations of words. Moreover, it is derived from the local community culture, thus refuting the charge of departing from the traditions of society and imitating the West and its languages that queer people are repeatedly accused of. Indeed, this shows that queer people have held fast to their mother tongues, creating a safe space for themselves instead of adopting foreign languages that their communities don’t understand.

In Libya, the queer lexicon boasts the inclusion of common local languages – including Tudaga, Tamazight, Arabic, and Italian – as our own dialect. This explains why our friends couldn’t understand the sentence mentioned at the beginning of the article, and indicates the most important reason for the invention of the queer language in Libya: safe and confidential communication. This is why I introduced the sentence without explanation, as this could put its users at risk.

This language of ours, and like its counterparts in North Africa, is often ignored. In the few cases where it is acknowledged, its historical-cultural specificity is overlooked. It is seen either as part of a “queer Arabic lexicon” or merely as local denominations that are affiliated to a queer language that is inclusive of the entire MENA or SWANA region.

العمل الفني: سمر زريق

Recently, some activists have noticed that this regional “affiliation” is populist and focuses on quantity,3 and is used to claim the privilege of representing the countries of the region on international platforms and before global donors. Such exploitation draws on the erasure of queer identities in North Africa, which have emerged through a history of interactions among human rights struggles as well as ethnic and cultural dynamics. It is reminiscent of Arab nationalism, which made no real effort to take the diversity of people throughout the region into account.

This is a serious matter, for the queer language encapsulates the culture of this marginalized group, including its needs, social circumstances and evolution throughout history. To be exploited in such a way intensifies its marginalization. Qardasha in Tamazight or delher in Tudaga have different connotations, depending on their ethnic or queer context, and to consider them both as Arabic or belonging to an Arabic queer lexicon is so shallow, considering distinct identities as one and the same. This is similar to the Orientalist approach, which combines different cultures under one classification.

Actually, this affiliation to the East is linked to another form of affiliation that is imposed on queer language in North Africa: the globalized queer model. Globalization stacks different societies under one category, thereby making it easier to turn these diverse groups into a single consumer.4 Queer groups in the Arabic-speaking region and the Global South stand against this, for this affiliation that has resulted from Western domination has led to a “linguistic invasion” of our own queer lexicons, through terms and concepts that aren’t necessarily related to local queer identities. Rather, they are linked to cultures that criminalized queerness in our countries during colonization.5

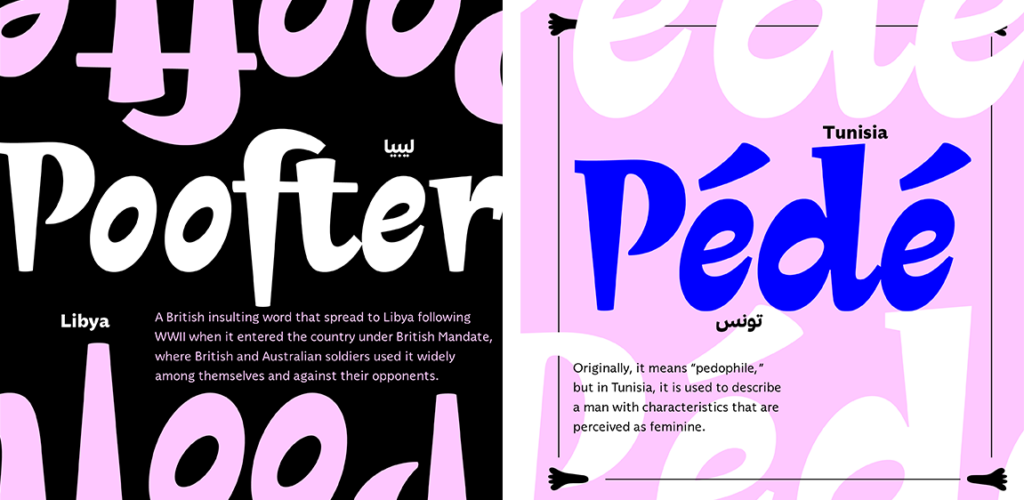

Artwork by Samar Zureik

For examples, insulting words like “poofter” (A British insulting word that spread to Libya following WWII, which entered the country under British Mandate when British and Australian soldiers used it widely among themselves and against their opponents) and “pédé” (an insulting word that the French brought to the countries they colonized – it literally means “pedophile,” but in Tunisia, it is used to describe a man with characteristics that are perceived as feminine) have become attached to gay people in North Africa. Once again, the same Western culture confines them to the LGBTQ term at the expense of local terms, marketing a queer life free from social restrictions and establishing a model of individualism in six bright colors.

This has been very much evident in using pinkwashing to rationalize oppression and occupation, as has been the case with Gaza, or to ignore the abomination of Western support for Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act. And then, there’s the continuing tokenistic6 inclusion of non-White queers in global conferences like World Pride. The common element among these three rationales is that they don’t resemble the Euro-American one, neither in appearance nor in language.

Having different queer languages in our region, therefore, is a testament to the distinctive patterns that make up our individual queer identities. This calls for an examination of their origins and terminology as independent languages, neither as affiliations of regional “Arab queerness” nor as part of the globalized West queerness. Such affiliations don’t necessarily reflect our local queer struggle. Rather, they transform these complex identities into copies that mimic a coercively imposed model. As such, we lose one of the most effective tools for resisting oppressive systems, i.e., our self-knowledge and independent queer roots.

Artwork by Samar Zureik

- Richard Kitterdege, “Sublanguages,” American Journal of Computational Linguistics 8, vo. 2 (Apr-Jun 1982).

- Anna T, “The Opacity of Queer Languages,” E-flux Journal 60 (Dec 2014).

- Focusing on combining the largest number of Arabic-speaking countries to gain support, visibility, and representation.

- For more details, see Rajab Podpus, Against Globalization, 1st edition, (Academy of Mass Thought: 2006).

- Retaj Ibrahim, “The Effects of Colonization on Culture and Gender in the Arab Region,” Raseef22, November 7, 2023.

- It is only symbolic for the sake of creating a fake scene of inclusion and diversity in a specific space, where marginalized groups are only superficially represented without achieving real equality in that space.