Words by Khaled A.

Artworks by Mloukhiyyé

This article is part of the “The Wawa Complex” issue

I grew up on the internet. The abundance of information there answered almost every question and curiosity I had, like when will High School Musical premiere on MBC Max? The internet also made the unfathomable possible. One of the many possibilities it introduced me to men who have sex with other men. For the longest time, I thought (or, rather, forced to believe) queerness was limited to attraction and not acting on it. All it took was scrolling on Tumblr to realize that men do, in fact, act on this attraction.

While I was in awe of the scenes of men being intimate with other men, what materialized on screen still felt distant – that it was only feasible for this to happen in far away contexts, not in Saudi. Shortly after, I found that the internet offered tools “for us,” ways that Arab men could find each other and cultivate intimacy (in person and virtually), while also maintaining the safety of full anonymity. It also enabled them to explore economic avenues like digital sex work that could’ve been impossible without this safety.

Finding Each Other

Though widely used, most dating apps are either banned or dangerous to use in many Arabic-speaking countries. Pop-up messages asking, “Are you sure you want to show your profile in this location?” open when you open Grindr and Tinder in Saudi, reminding users of these risks every time they open the application. Social media platforms, on the other hand, provide a safer way for people to meet. Because they aren’t explicitly for the purpose of finding partners, this pathway can shield users from random inspectors or police. And, they are more accessible and more customizable; aided by hashtags, users are able to narrow down what they’re looking for to the highest degree of accuracy.

The first post listed a number of keywords and physical traits: city, age, body type, sex position, ability to host, etc. A 35-year-old man from Hafr Al Batin posted it; his username was a combination of random letters, and he had few followers. The profile photo was a stock image, and his posts were all reiterations of a similar post. He was asking people who matched the description of the post to DM him; his DMs were open.

This kind of post is standard procedure in this system of finding your match. First, you search for keywords, looking both at what users are looking for and what they offer. The next steps differ slightly. Some exchange body pictures or ask where specifically each other lives. Some share their family name or images with their face based on comfort level, while others prefer to meet in public first.

Though the process varies based on who’s meeting, these exchanges ensure the potential partners get a sense of each other’s identities without revealing any “traceable” data that could be shared with a friend, relative, or someone else. Rather than taking this as simply a limitation, we should see it as pursuing a connection on their own terms, one that maintains their level of comfort.

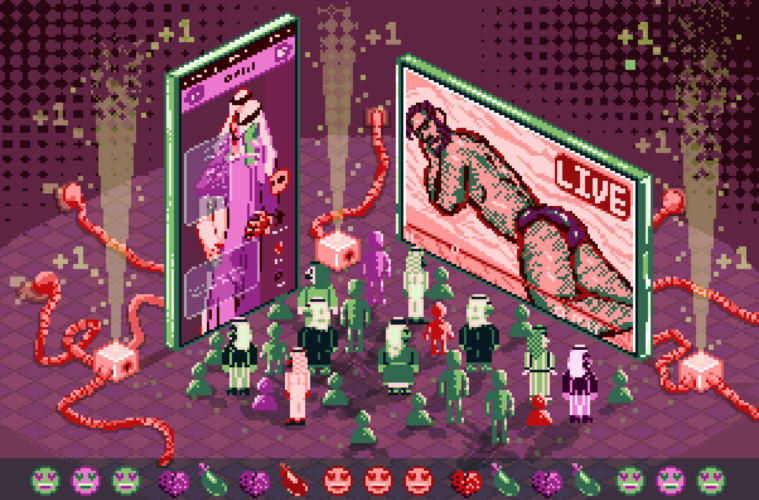

Artwork by Mloukhiyyé

Online Matchmaking

I came across a matchmaker who has 65K followers and a backup with 6,000. They don’t share their personal pictures or information, but instead, use the account to post about men who are seeking to connect, videos users find or receive, and polls like, Which number in this picture represents your dick? To participate in this audience engagement (whether it’s posting a caption or sending them pictures), you simply have to DM them.

Like the individuals posting on social media, these posts rely on a series of keywords. But here, visual aids (i.e., body pictures, nudes, videos, either of themselves or the type they’re looking for) are required to expedite the matching process. Endless torsos and videos of partial bodies appear as you scroll through these accounts. Men – from Morocco to Egypt to Iraq to Qatar – connect based on their relative proximity, and, if they are distant, whether there was a possibility of a visit or video call. Nothing about these interactions is traceable; the information shared is vague, and the videos usually don’t include a voice (whether spoken words or moaning).

Some users only engage with this visual content, with no intent to meet up or reach out. The pleasure is in sharing and viewing. The videos follow a similar formula – not exceeding 50 seconds, they show bodies in the midst of the act (either without faces or the faces obscured). A few of these are traceable back to nationality. Of course, this system isn’t perfect, and some videos or personal information leak. One Egyptian user found a video that he’d made seven years ago circulating across multiple accounts; he had no idea how they found it and spread it so widely.

Sex Work on Screen

Platforms like OnlyFans offer a third route to engage with queer intimacy. Some users capitalize on these videos, collecting “rare” or “never-before-seen” videos and uploading them to a streaming service. They’ll even post a list of instructions to access the often-banned pages. Oftentimes, these archive older videos that have been leaked and others online. One account with over 25K claims to offer the “largest library of real Arab porn.” Maybe the “realness” is what keeps subscribers following and engaging with content; followers find it relatable and reflecting the circumstances of their sexual experience.

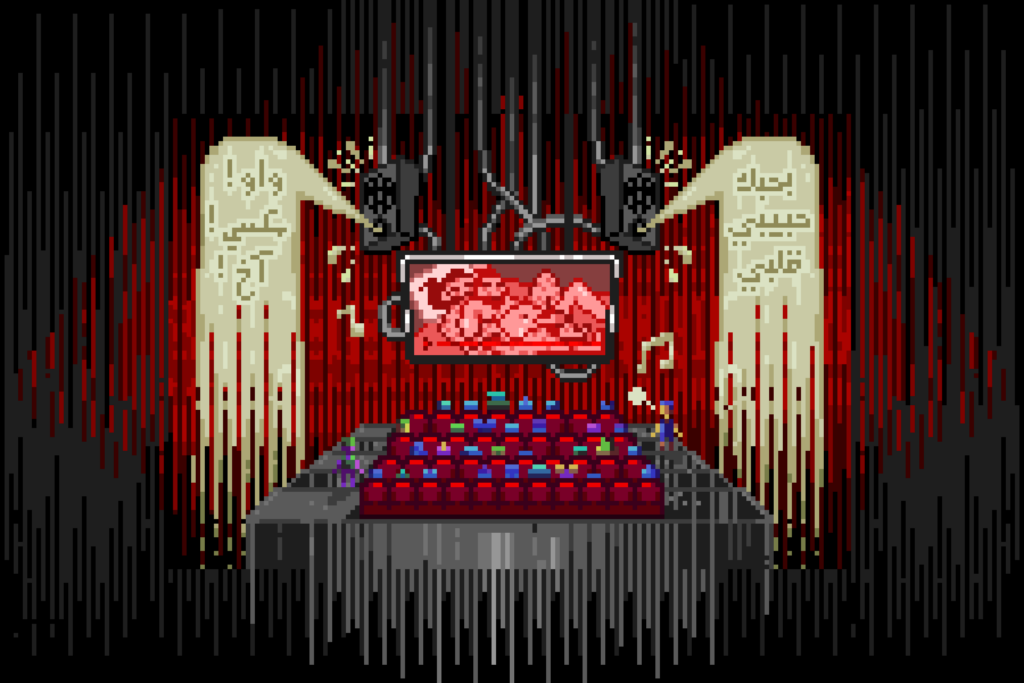

Artwork by Mloukhiyyé

Other users create and share original content on these platforms, and there is a rising demand for content that is both original and relatable. One Saudi creator with over 48K followers, who lives between Riyadh and Qatar, posts videos with consenting men and women who want to meet. He’s uploaded over 200 videos, each with its own clickbait title and culturally-specific scenario, which add another level of relatability. Meeting a man at an azooma1 but ending up topping him, and another shows a guy flirting with another on his soccer team. On a similar account with 44K followers, an Egyptian creator produces relatability by wearing a galabeya2 in his videos. Other creators – like a Syrian creator with 10K+ followers based in Turkey – film not their experiences with clients rather than their meetups, including those with tourists.

Exceptions and Cultural Specificity

While anonymity is the general standard in the region, some do show their faces and obscure those of their partners. Due to the risks, however, this is more common with Arab content creators living abroad. Their audience is still Arabic-speaking men in the region. You can tell from the language used in the videos and captioning practices, even when having sex with non-Arab men. Others, still, circulate porn produced in Western countries but adapt them to the context using captioning and culturally-specific scenarios similar to those from the region.

These diverse forms of “culturally-specific content” make us wonder what it is that appeals to the user – is it the image depicted, the scenario, the language, or a mixture of all of them? While there isn’t a clear way to answer this without extensive interviews, it’s likely that familiar contexts (or contexts reframed or reimagined) allow viewers to engage differently, and that the use of Arabic makes the content more accessible through keyword searches.

Conclusions

Of course, there are many ways that queer Arab men in the region connect, both on the internet and beyond, and there is a history of men-having-sex-with-men and being empowered in their identities. But, the presence and circulation of these images and forms of intimacy online provide an alternative way to seek pleasure and intimacy, and show us the creativity that people develop to navigate the constraints of censorship and safety.

Instead of relying solely on dating apps and the risk they might impose, queer Arab men have utilized social media platforms to create social networks of people that both live in close proximity (who they could potentially befriend, date, or have sex with) or around the globe. They used the features of each platform, such as hashtags, to seek what they are specifically looking for. These individual interactions later morphed into unspoken rules of how, when, and what information and pictures they should and could share on these public platforms and with each other.

“The rules,” which emerge from a specific cultural context, have paved the way for new avenues for queer Arab men to explore, connect, and capitalize on. The rising demand for and engagement with this content – original or archived, social and independent – that represents and resonates with the viewers, reveal both the desires of the people but the shortcomings of the current sex and intimacy industries. In fascinating ways, queer Arab men are producing their own virtual worlds of pleasure and intimacy on their own terms.