Words by Leila B

Artworks by Omar

This feature is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

We are in 2015, and I’m sitting in a bar in Downtown Tunis—one of the few “queer” bars back then. I’m wearing an ankle bracelet gifted by my mother, a thread with evil eyes for protection. “It’s a lesbian thing,” said my high school best friends, who are low-key mocking me. It didn’t seem like a thing, but then, from across the bar, a girl with curly hair looked at me, from ankle to eyes, and smiled. Startled, I didn’t smile back; it was the first “gay gaze” targeted toward me.

It’s easy for me to recognize a lesbian. Of course there are variations, but sometimes it’s a cuffed t-shirt or pants; “jorts” or suits, flannels or a dad shirt, funky sunglasses or glitter, septum or labrys piercings. But since “dressing like a dyke” is finally perceived as cool, and camp is no longer seen as grotesque, it’s become difficult to say who’s queer, who’s straight, or who is in-between.

Recently, my partner questioned how my social circle in Tunis could remain so oblivious to my queerness. I told her that I can tone down my signaling, morph into the Tunisian girl-next-door through a different hairstyle or combination of feminine clothing. But still, there’s something in the body that remains outside of this, that stays, that isn’t quite right.

What does it mean, really, to “look queer” or signal queerness in a city like Tunis? How does the city’s atmosphere facilitate or constrain the movement of queer signaling? How has our mundane existence in the streets of Tunis shaped our strategies for signaling? How do we, as women, negotiate the assumptions and misrepresentations about what queerness is or means?

For this article, I spoke with queer women and friends about their experiences navigating spaces by signaling queerness. Though I had a set of questions prepared, I gave them space to speak openly, at times diverging from the central topic.

On Appearance and Signaling in Tunis

I’m not the only queer to observe the mainstreaming of lesbian fashion. Scholars, social media theorists, and our community have engaged in this discourse for decades. Art historian Reina Lewis,1 wrote about the challenge of appearing fashionable and remaining aligned with evolving trends while still conveying a lesbian identity. She remarked, “At one time, it was relatively simple: you wore whatever you wanted and paired it with large shoes or boots. But then, everyone started wearing Doc Martens, and the lesbian coding of footwear was compromised.” These shifts challenge the concept of the “hanky code” that queers around the world developed to signal their identity without being at risk.

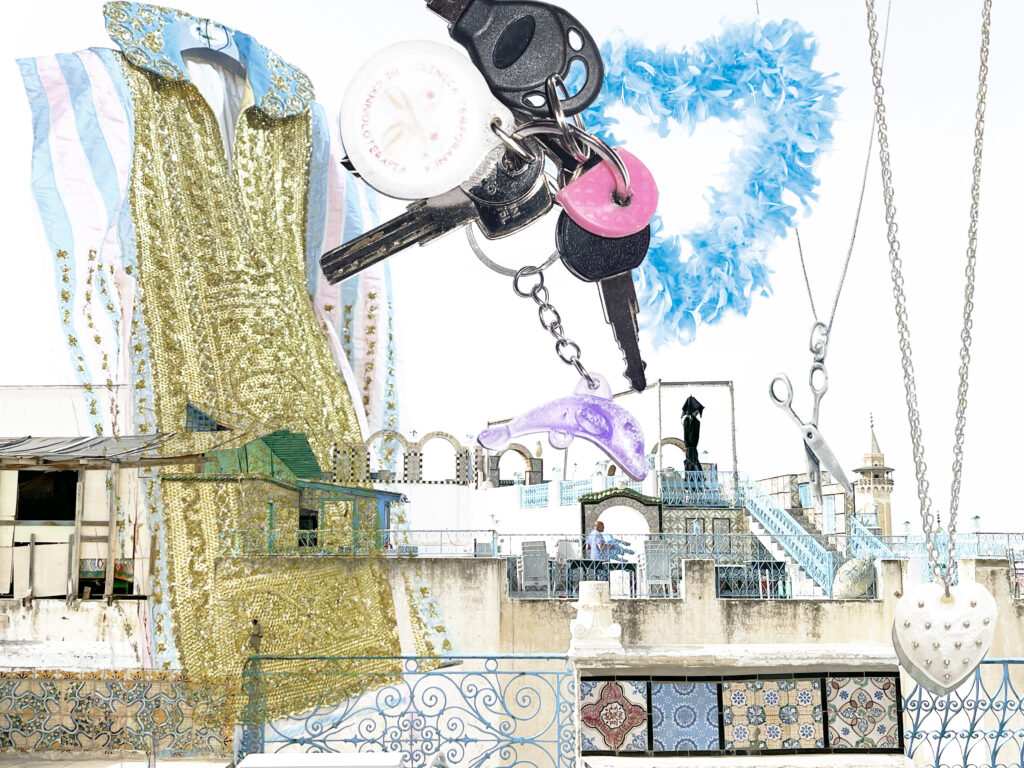

Artwork by Omar Khlif

I wondered if we had such practices in our communities in Tunis, where being queer is still criminalized.2

When I talked with Z over the phone, she said that signaling requires a certain awareness. “Not everyone is aware of who the queers are or how they dress. When I signal in Tunis, I feel like it’s targeted to other queers – if it’s subtle. People are not necessarily aware of queer codes, or queer pop culture.’’ Z – who dresses in a way that attracts queers while not alarming those who hate them in Tunis – continued, ‘’I’m lucky because I seem to have a ‘“non-concerning style.’” I like to wear baggy stuff, keys on my jeans (carabiner), necklaces and rings. Also, not a lot of makeup when I want to be more ‘queer coded.’”

Increasingly agreed-upon international signals of being queer (i.e. cuffed pants, tote bags, bleached hair) have become instrumental for recognition within the community in Tunis, in part because many locals aren’t well-versed in the intricacies of queer culture that are filtered through algorithms, which often filters through their interests.

C echoed this, saying it’s all about the mastering of subtlety. She presents herself in a manner that challenges certain heteronormative expectations associated with “femme presenting” women, for example, by not shaving her arms or legs and opting for tattoos and piercings. These choices, for the most part, might not attract much suspicion or draw the attention of the police. Signaling, then, becomes this thin line where you balance how much queerness you can show without attracting the suspicion of the general public.

For some, signaling queerness doesn’t primarily involve appearance, but rather the gaze and communication with others. Q highlighted the unease associated with conversations about hair and clothing as a means for signaling, saying that the butch-femme continuum imposes restrictive categories.

On Signaling in Public Spaces

Building on this, I asked if there were particular spaces where people feel comfortable signaling their queerness. The overwhelming response was the same bars, cafés, and spaces. Z said that there were “queer friendly” clubs, those that are not too “posh or fancy,” and that a lot of arts spaces, underground screenings, and exhibitions were generally safe. C and K agreed, but said that it wasn’t necessarily the place, but the crowd or consumer profile, that made it feel safe to signal. They said they are drawn to places already frequented by other queer individuals, and that the owners’ policies – whether behavior or door policies – lead the way for this.

There’s something beautiful about our marginal communities in Tunisia, which is that all minorities come together. It’s a sort of unconscious intersectionality of struggles: the metalheads, the queers, the atheists, the beer-drinkers – we all come together in this space to be ourselves.

S named a couple of bars where she feels safer being herself, where there is a notable presence of other queer individuals who are openly signaling, particularly through butch or other recognizable aesthetic categories. In these bars, people wouldn’t hesitate to show affection more openly. She says she’s more subtle when with a lover in the street, reducing the “flirtiness, because it happens behind closed doors.” I chuckled, remembering the adrenaline rush on a warm night in July, when I kissed a girl in one of the bars S had mentioned.

Most women I spoke with mentioned the issue of class, regardless of their background. Growing up in an upper-middle class milieu, I never felt like my queerness was an issue, as long as I signaled in a “toned down” way or didn’t completely embody a queer stereotype. But wealth generally protects people from a lot of risks that lower-class queers encounter. The safer you feel, the more willing you are to engage in riskier conversations.

Signaling queerness may also be an urban phenomenon. There is a sort of ephemerality or fleetingness to these “safe spaces.” The city is ever-changing; permits and bar licenses are not always renewed, especially when authorities get intel that are frequented by queer crowds. It feels like queers have to be nomads in Tunis.

Artwork by Omar Khlif

In Europe, there are often tensions around who “can” or “should” frequent gay spaces, reflecting distinctions made between gay individuals.3 In contrast, many respondents shared how welcoming Tunis’ community was, that these spaces felt less exclusionary. Q said, “As a matter of fact, I never thought about this question or felt unsafe in Tunisia. Queerness between women has always been normalized in my mind, and in my environment’s mind… There’s something beautiful about our marginal communities in Tunisia, which is that all minorities come together. It’s a sort of unconscious intersectionality of struggles: the metalheads, the queers, the atheists, the beer-drinkers – we all come together in this space to be ourselves.”

On Signaling and Relations to Place

Is there something about our culture, our appearance, or ways of moving our bodies that is inherently queer, or inherently erotic, even? Last summer, while sipping a lemonade at a seaside bar with sweat beading on our foreheads, Younes said “There’s something so erotic here, in the air. Something in my skin activates. I feel more queer here.’’ ‘’Maybe it’s just the heat,’’ I replied half-ironically.

Queerness can sometimes be perceived as antithetical to our identities as North Africans or Muslims. But when looking at Arab Pop Culture footage – whether music videos, old films – some content is reminiscent of camp aesthetics, if not queer ones.4 Intentional or not, these representations existed long before flannels or viral queer outfit TikTok videos.

In a voice note, S told me that she feels like she’s white passing or passes as a tourist. “I feel like white people get a pass for being weird, or passing differently or dressing differently to the culture.” Not originally from Tunisia, she said she doesn’t encounter negative attention while navigating the streets, and isn’t burdened by the weight of religious expectation. Still, she hesitates to display her queerness or bear international “gay symbols” like rainbows. Her caution isn’t specific to Tunisia, but stems from her will to not be defined by stereotypical gay representations that have been co-opted by liberal queers around the world.

This also hints at queer individuals’ in Tunisia’s relationship to visibility and “coming out,” which is not always feasible or desired. Being openly queer, in the public eye, can be equated to Eurocentric norms, and also may not resonate with cultural or historic contexts. One respondent reflected that, on the one hand, she doesn’t feel like her queerness was affected by Tunisian culture because she “grew up on the internet” and was “exposed to every type of queer expression from a young age.” But, on the other, she feels like it’s impacted her notion of safety and, as a result, how she expresses herself. So, it’s not necessarily culture that impacts choices of how we signal, but connections with or accessibility to mainstream international queer culture.

Artwork by Omar Khlif

The question of how we, as women from the Global South, relate to these viral queer aesthetics is an interesting one. Do we want to look like other queers? Do we approach these aesthetics with disdain once they are co-opted by the queer international, who we differ from so much? Or, is it something in-between?

Signaling in a city like Tunis is a dynamic process. As the city changes, bars close and open, and queer people gather in new spaces, and as signaling becomes an issue of navigating the desire for recognizability or risk, we find ways to negotiate beyond the borders of our community.

- Reina Lewis, “Looking Good: The Lesbian Gaze and Fashion Imagery,” Feminist Review, no. 55 (1997): 92–109. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1395789.

- Ramy Khouili and Daniel Levine-Spound, “Article 230,” 2019. https://article230.com/en/article-320-eng/.

- Tyler Baldor, “No Girls Allowed?: Fluctuating Boundaries between Gay Men and Straight Women in Gay Public Space,” Ethnography 20, no. 4 (2019): 419–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26785600.

- Aya, El Sharkawy, “Another Camp or The Second Testament on Camp,” Kohl 6, no. 3 (December 17, 2020): 256-268. https://kohljournal.press/another-camp.