Words by Sirine Germany

Artworks by Heba Tarek

This piece is part of the “Frenquencies” issue

Wars, bombings, socio-economic collapse, nothing seems to hinder Beirut’s partygoers from staying up till dawn, often in world-renowned clubs charging exorbitant fees. From laid-back Jazz bars to trendy venues pulsating to electro tunes, Beirut’s nightlife caters to a wide variety of tastes for those who can afford the experience.

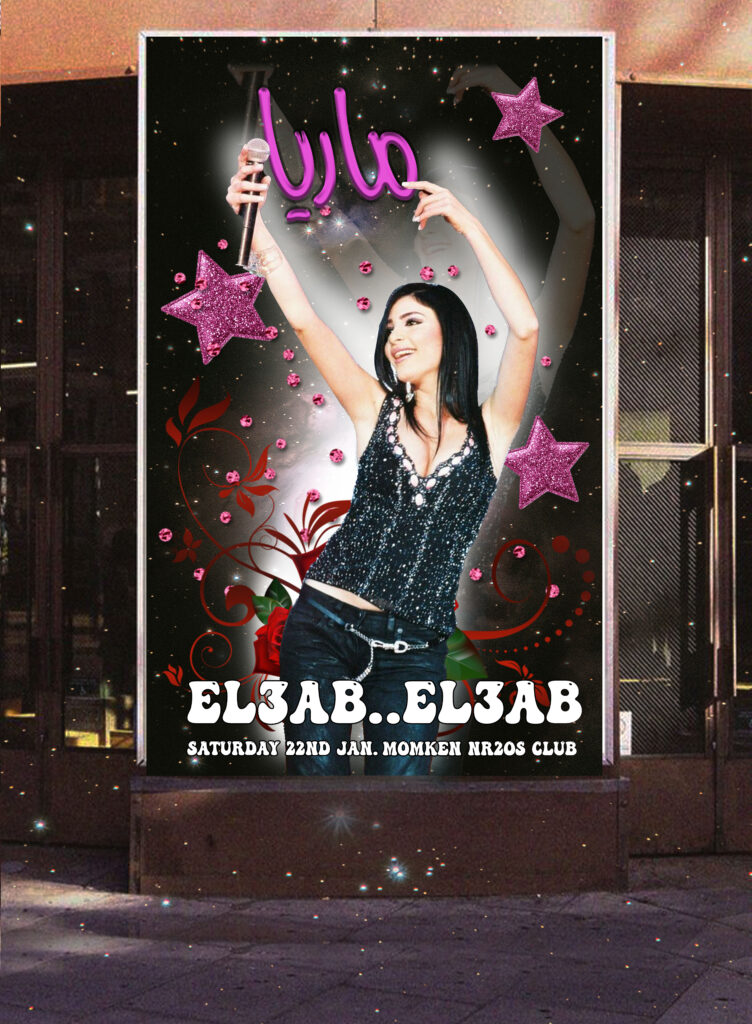

Amongst the opulence of Beirut’s venues, a scattered queer nightlife scene reverberates behind concrete walls of industrial quarters and back alley bars. This nightlife differs significantly from the rebellious underground scenes of cities like Berlin or Paris, as techno and punk take a backseat to Arab pop hits, featuring beloved artists like Haifa Wehbe and Nawal el Zoghbi. The night frequently culminates with upbeat remixes of classics from Umm Kulthum to Sabah Fakhri, sharply contrasting with the Westernized atmosphere of the rest of the city.

In the Lebanese capital, where signs of Westernization are proudly flaunted as a symbol of elite status, the queer community carves out an alternative space. Through the medium of Arab pop music, Arab queers assert their rightful place in a society that has long marginalized them. Dancing to these tunes serves as a powerful tool to challenge societal stereotypes surrounding class, gender, and sexuality while asserting an identity that is unapologetically Arab.

Paris of the Middle East?

Hailed as a “party city” and the “nightlife capital” of the Middle East, Beirut emerged as a center for leisure and nightlife long before it became a jet-set playground in the sixties.1 But even earlier, during the late 1830s, travelers were already describing Beirut as the “Paris of the East.”2 Beirut quickly metamorphosed from a burgeoning center of trade into a thriving port city. Its affluent mercantile class developed a taste for European culture, fashion and art, building opulent new mansions influenced by European architecture, alongside hotels, billiard rooms, and cafés with elegant interiors.3 The city’s cosmopolitan character and relatively tolerant culture, attributed to its mercantile activity, held a magnetic allure for visitors and tourists alike. Commerce and trade require a willingness to mix and interact with “all sorts of people.”4

Artwork by Heba Tarek

Travelers, especially those arriving in Beirut after touring other cities in Syria and Palestine, were captivated by Beirut’s “European” and “cosmopolitan” character. They chronicled the city’s lavish lifestyle and a sense of unrestricted freedom.5 For instance, in 1842, British traveler Frederick Neale praised the stylish lounging bars and Italian locandas. He humorously recounted the evening quadrille parties, musical gatherings, and balls to which “the elite of every religion and attire were invited,” and where the latest polkas and waltzes were expertly performed.6

The orientalist imagination envisioned Lebanon in European terms, as a “heaven of freedom” amidst “barbaric” Arab surroundings.7 Cultural and economic liberalism made it a prime destination for banking and tourism.8 As inequalities mounted, this identity consolidated into “Paris of the East” during the golden 60s attracting international celebrities, royals, and elites to dance the twist in Les Caves Du Roy and indulge in more licentious activities in the infamous Crazy Horse on Phoenicia Street. In 1975, the civil war put an abrupt end to this state of drunkenness.

A consumerist identity in a traumatized society

The Lebanese, who notoriously partied through the civil war, managed to maintain their reputation as careless party-people until 2020. When the turbulent events of that year – the financial collapse, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the devastating explosion at the Beirut port – sent shockwaves through the fabric and psyche of society, it seemed like it would be the final blow to Lebanese nightlife. The national mood darkened, parties became less frequent and more discreet, and extravagant excess was eyed with disapproval.

However, in an absurd turn of events, Lebanon seemingly returned to its old ways in the summer of 2023. Private beach clubs were packed as partygoers flocked to upscale restaurants, bars, and sold-out nightclubs. Night revelers donned their stilettos and Prada bags, vying for entry into selective clubs, where affording the sky-high prices offers no guarantee of access. Deafening electronic beats, valet drivers competing over roaming engines of luxury cars, and frustrated screeches at non-negotiable “not on the list” verdicts were celebrated as a testament to the indomitable spirit of the Lebanese people. Internationally renowned DJs enthusiastically found their way back to Beirut’s clubs. The world-renowned Sky Bar reopened its doors, popping 400 USD bottles of Dom Pérignon champagne to eager, well-dressed customers.9

These alternative spaces are both inclusive and relatively affordable, upending the foundational myth of Beirut’s nightlife as an “exclusive” enclave for Westernized elites.

In most societies grappling with uncertainty, economic instability, or political unrest, one would expect the impulse to amass and flaunt material wealth to disappear.10 However, Lebanon mirrored its postwar self, as the taste for lavish spectacle grew again.

During the war, Lebanese people became desensitized to violence, moral indifference towards violence grew through the “othering” of the groups at its receiving end,11 such as protestors, refugees, or queer folk. In the face of attrition, people reasserted communal (sectarian) solidarity12 and by seeking solace in the consumption of an ever-changing array of material goods, experiences, and cultural products. The penchant for extravagant displays of wealth became a defining feature of national identity, offering a shield against the vulnerability of a fragile collective bucking under the weight of constant threats.

Carving queer spaces and resisting class narratives

An alternative queer scene emerged after the civil war, running parallel to Beirut’s mainstream nightlife. Acid, a renowned LGBTQ-friendly dance club founded in 1998, pioneered a space for the queer community to dance to the rhythms of Samira Saad and Warda’s “Batwanes Beek.” The city experienced a surge in queer-friendly spaces during the reconstruction period, including iconic nightclubs like Orange Mechanic, ROH, Mint, and more relaxed hangouts like Wolf and Sheikh Mankouch.

Although the forceful closure of Acid in 2010 marked the onset of a series of events that would significantly reduce queer-friendly spaces, those that remained continue to be sustained by popular Arabic music and culture. These alternative spaces are both inclusive and relatively affordable, upending the foundational myth of Beirut’s nightlife as an “exclusive” enclave for Westernized elites.

Artwork by Heba Tarek

Through this music, Lebanese queer folk can carve a space for themselves and reclaim their place in a society that has long silenced them.13 Acts of listening and dancing together to Arab pop music upend the prevailing discourse that portrays queer communities as the product of “Western” values to justify violence against them. Every drumbeat of “Shik, Shak, Shok” or the tearing vocals of “Mandam Aleik” becomes a vehicle through which the marginalized and increasingly oppressed queer community asserts its rightful inclusion in a society with which it shares similar expressions of love and heartbreak.

However, this demand for inclusion should not be misconstrued as a desire to conform to the oppressive moral norms of gender, sexuality, and masculinity that were imported and enforced by colonial dominion. By dancing to popular Arabic music, the queer community pushes back against the foreign, prudish, and intolerant norms14 that deemed the act of men practicing oriental dance a threat to Western Victorian morality.15 This dance revives parts of their pre-colonial heritage, where homosexual sensuality was integral to “Arab” culture and art.

Defying threats to Beirut’s diversity

Beirut’s queer community forges a unique identity that proudly embraces Arab culture while resisting its oppressive norms. It counters both local and foreign threats to its eroded cultural identity and reclaiming integration into the contested public spaces of the city by carving out alternative inclusive spaces.

Amidst rising austerity, Beirut is witnessing a worrying surge in violence, exemplified by recent homophobic attacks on a queer-friendly bar16 and protestors of a “freedom march,”17 leading to a series of cancellations of queer-friendly events throughout the summer of 2023. Rooted in a sustained history of marginalization, members of the LGBTQ+ community, particularly the most vulnerable, have increasingly been pushed to secluded spaces at the outskirts of the city. These spaces are evolving into increasingly perilous and violent environments away from public attention.

This surge of homophobia is symptomatic of a broader concern of growing violence and the widening of groups at its receiving end in a city grappling with an identity crisis brought about by economic collapse. Fighting to preserve Beirut’s history of diversity and freedoms, and reclaiming the contested public spaces of the city, requires collective action beyond the queer community alone, especially as the recent events worryingly echo sectarian undertones of a yet unresolved civil war.

- Samir Khalaf, Lebanon Adrift: From Battleground to Playground, (Saqi Books, 2012).

- Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf Volney, Voyage en Syrie et en Égypte, pendant les années 1783, 1784 et 1785, (Volland [et] Desenne, 1787).

- Khalaf, Lebanon Adrift.

- Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon, (Pluto Press, 2012).

- Samir Khalaf, Lebanon Adrift: From Battleground to Playground, (Saqi Books, 2012).

- Frederick Arthur Neale, Eight Years In Syria, Palestine and Asia Minor V1: From 1842 To 1850 (1851), (Kessinger Publishing, 2008).

- Volney, Voyage en Syrie et en Égypte.

- Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon.

- Raya Jalabi, “‘It’s cool to have money again’: wealthy Lebanese party out the crisis,” Financial Times.

- Khalaf, Lebanon Adrift.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John Fiske, “Shopping for pleasure: Malls power and resistance,” in The Consumer Society Reader, eds. Juliet Schor and Douglas B. Holt, (New Press, 2000), 306-328.

- Joseph Massad, Desiring Arabs, (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- Alphonse De Lamartine, “Souvenirs, impressions, pensées et paysages au cours d’un voyage en Orient (1832, 1833),” in Œuvres complètes, tome 7, (Paris: author’s editions,1861).

- Lebanon drag show derailed by crowd of angry conservative men

- Lebanon: Investigate assault on Freedom March protesters