Interview by Khaled A.

Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe

Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez

Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

Cover design: Atef Daglees

Video cover design: Alaa Saadi

This article is part of the “Ya Leil Ya Eyein” issue

I think of Tim Dean’s work on being queer: Queer not as being about who you’re having sex with (that can be a dimension of it);… queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and thrive and live.

As she was getting in drag in her apartment in New York City, 31-year-old Lebanese drag queen Anya Kneez received a text from one of her friends saying, “Did you hear what happened in Beirut? Is your family okay?” Anya immediately sat down and Googled what happened, not knowing what to expect. From dealing with an economic collapse to handling a pandemic, Lebanon was already going through enough. She was shaken.

At around 6 pm on August 4, 2020, large amounts of ammonium nitrate stored in a warehouse at the Beirut Port exploded, killing around 220, injuring over 7000, and displacing over 300,000 people. The most vulnerable communities were affected. The damage caused by the explosion reached as far as 20 kilometers away from the Port, mainly destroying the Mar Mikhael and Gemmayzeh areas. These were the same areas where Anya had first performed in drag in Lebanon, where many of her loved ones lived and worked. These were also the same areas considered safe for the LGBTQ+ community in Beirut.

Distressed by what her people were going through, Anya looked for ways to support from afar. With the help of her queer family, she was able to organize a fund and raise awareness about the struggles the Lebanese queer community are facing. Anya was familiar with what it meant to be a queer person in Lebanon: excluded and struggling to belong and survive.

In this conversation, Anya delves into the details of this journey: from her yearning for a queer family growing up and pioneering the drag scene in Beirut, to organizing a fund to help LGBTQ+ victims of the explosion and creating a platform that exceeds the limits of social media. Anya’s passion for drag and performance enable her to both escape and confront the reality of living in current day Lebanon. And she’s taking us on this journey with her.

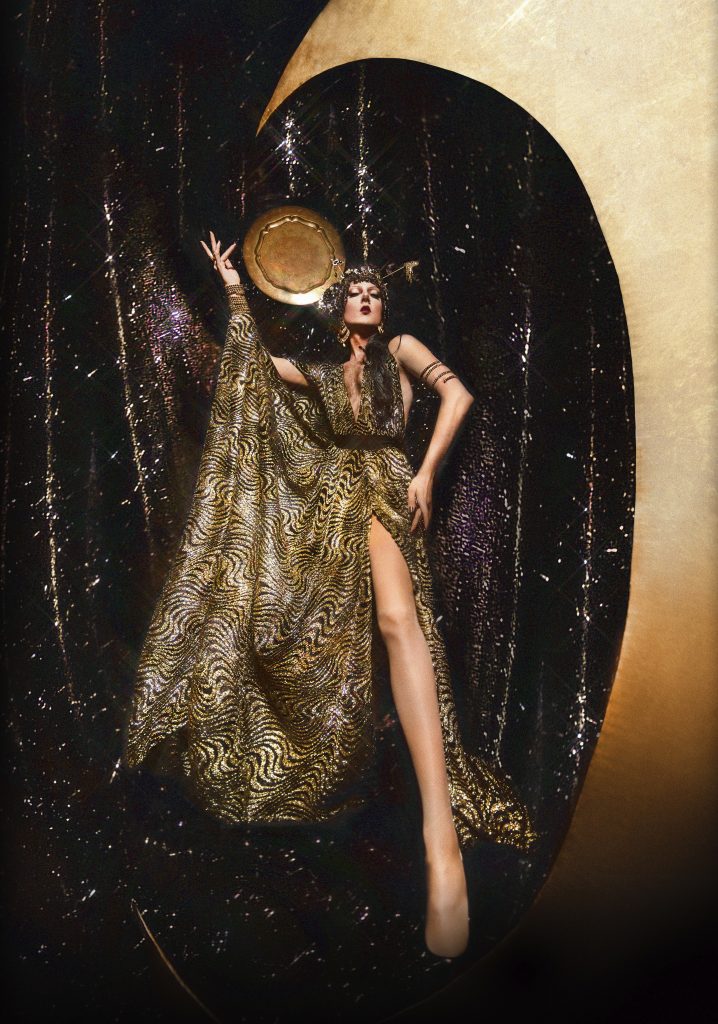

Double slit dress designed by Anya herself. Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe. Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez. Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

Tell me more about your background. What in your upbringing led you to do drag?

I’m originally Lebanese but was born and raised in California. Both my parents are Lebanese and I was raised in a very Arab way. My parents taught me Arabic since I was a kid, which is why I’m fluent in Arabic now. We used to go to Lebanon every summer. They always wanted us to be immersed in the culture. Because they’re immigrants who left Lebanon during the war in the 80s, they wanted to hold on to any sort of Lebanese culture they had left and to kind of bestow that upon their kids as well.

I studied fashion in New York City in 2010 and I moved to Lebanon after my graduation in 2012 to visit my family, who had moved back two years prior. They had been in America for 30 years, but always wanted to return when they retired. I went to visit them but wasn’t planning to stay because I never saw myself living there as a queer person.

I feel like I came into my own when I moved to Brooklyn, where a huge queer scene already existed. I was living with drag queens and that’s how I started dabbling in drag. Studying fashion also went hand in hand with it, and I’ve always had a love for performance art. It happened naturally. I think that once you’re surrounded by a group of people who inspire and push you, you kind of just fall into it.

In early 2012, an NYC collective of Arab and Middle Eastern queers that I was a part of called “TARAB” were having a party, and one of my friends asked if I wanted to help out. So I thought of ways I could lend a hand at the party and I said to him: “Well I have been doing drag for a few months so I can come and perform!” And I did! I always go back to that night because that was the night I feel like Anya was really truly born. Even though I was doing drag before that, that was the night I realized that I can be Arab and queer simultaneously. I had never really experienced my [Lebanese and Arab] culture within my drag or my queerness before, and that was the night that really brought that out.

You’re one of the pioneers of the drag scene in Lebanon. Can you tell me how and when it began?

I moved to Lebanon a few months after my show at the TARAB party in New York. It was as if someone plucked me out of a queer Mecca (this beautiful, flourishing queer scene in NYC) and dropped me into the heart of the Middle East. I went to live with my parents, who I am still not out to. I had all my drag at home (wigs, dresses and makeup), but they never put two and two together. I think because I worked in fashion, they just thought I’m an artist or whatever.

The first few years were really, really hard and I was depressed. I was dying to witness a queer community in Beirut, a community that accepted femmes. There’s still a lot of toxic masculinity and misogyny in the Middle East, especially in the gay community. A queer person who looks feminine was looked down upon. I just wanted to put a wig on and perform and be on stage, but I couldn’t. I was missing a queer scene and I was missing out on drag. I wanted to do all of these things but there wasn’t a platform for me to do that in Lebanon.

There was this moment, though, when I was watching an interview with Susanne Bartsch. She was talking about moving from London to New York in the early 80s, she said she felt that New York was missing something that London nightlife had — the aspect of mixing performance art with nightlife. She said, “If you miss something really dearly, then don’t wait for anyone else to do it. Do it yourself.” I thought, how have I never thought of this before?!

Of course, this is not a one person job, you have to do it with like minded people. That was when my friend Evita Kedavra and I contacted Sandra Melhem, who is the founder of the Queer Relief Fund who also owns a gay club in Beirut called Projekt. We did our first drag show there in 2015.

Dress designed by Anya herself. Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe. Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez. Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

How did audiences and venues respond to this initial wave of drag performances, particularly because they were taking place in an Arab country?

During 2014 and 2015, we were testing the waters by going to private queer parties, someone’s birthday, someone’s event, etc. We wanted to see if people would be into drag and how they’d react because it was something very new for Lebanon. Even Bassam Feghali, who is considered by mainstream media to be a female impersonator, doesn’t call themself a drag queen. They knew they would not have been as successful if they did, and was smart about how to incorporate what they wanted to do into heteronormative Middle Eastern standards of mainstream media.

We felt like people were kind of into it and responding well, so we did our first show in 2015 at the opening night of Projekt. A lot of people were just staring at us and giving us weird looks. Also, I was a bearded queen at the time, and people would come to me and say, “Well, if you’re trying to be a woman, then why don’t you shave?” That night felt like a TED talk and I had to sit people down and say, “You have to understand that I’m not trying to be a woman: I’m not a woman. And I’m paying homage to femininity, in the way of performance art.” It was important to introduce people to what drag was and wasn’t about: it isn’t about trying to be another gender, but playing with gender roles and the idea of queerness.

A week later, we performed at a gay bar called Bardo. I think they had seen our show at Projekt and asked if we could do another show there. We spent the whole summer of 2015 performing, and that was the start of our movement.

How did drag performances help increase the visibility of trans and queer people in Beirut?

Slowly, we started seeing a very young generation of queers (17 or 18 years old) coming to our shows and feeling very inspired and wanting to do it. People were also starting to watch RuPaul’s Drag Race at that time, and were gaining an understanding of drag on an international level. They began to understand that it’s not only about makeup and hair; it’s about performance, it’s about saying something, it’s about unleashing a persona that is within you. These young people would come in heels and makeup, and this was a space for them where they could truly be themselves. I would always encourage them because, for me, the whole point of drag is to create a sense of community. It was fun when we were two queens in Beirut doing it on our own, but it’s not as fun as having a community, a scene, and a group of people to collaborate and create content with.

It took six years since the first show to build a “scene,” which is a very short amount of time. We planted a seed and suddenly all these young people wanted to be a part of it. It made me even more proud to be able to share my love for drag and my love for experiencing queer life to its fullest.

One very important thing is the fact that we are talking about drag in the Middle East. I never thought that I would be able to be queer or to do drag in my home country. I never in a million years thought that would be possible. The fact that we were able to do it and cultivate safe spaces for people was especially important because it’s very difficult in the Middle East.

Safe space is the keyword here. We needed to provide a good amount of safety for people if they were to come in heels or in a little bit of makeup because we could easily be put in prison for something. But have been able to work with people who had connections with the government or were able to pay people off, and to put in extra security measures. It’s important to say this because people often look at the abundance of the queer or drag scene in Beirut and think it’s easy.

Dress designed by Anya herself. Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe. Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez. Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

Despite these challenges, what helped you cultivate this scene?

Social media played a big part of the acceptance of the queer community in Beirut and as queer individuals in the Middle East. I’ve been doing drag for ten years now, but it took me until 2017 to open my Instagram account. I was so scared to post my face as a boy without makeup, especially because it might get to my family. I was always very careful about what to post and made sure that people couldn’t recognize me out of drag. Moving back to New York allowed me to come out on social media and now I couldn’t care less about people seeing me out of drag.

Taking those safety measures was important even when preparing for a show. In Lebanon, I was living with my parents. I had to put Anya into a suitcase, take her to the venue, get ready there for two or three hours, do the show, have a little fun, and then take it all off and then go home as out of drag. I was never seen in drag in the public eye or on the streets. I never took a cab in drag.

I’ve mentioned this many times to the young queens in Lebanon. Because many of them receive so much support on social media, they think that they don’t live in Lebanon. I’ve seen some of them get ready at home and then take a taxi to the event, and that frightens me tremendously. There’re so many police checkpoints in Lebanon wherever you go, so if you get stopped, God knows what they can do to you. I would always tell them to be more careful and cautious

The younger generation in Lebanon is much more courageous than we were 10 years ago, and I think this is definitely because of the people that came before them that made it easier along with a big thanks to social media. They think Beirut is New York, where they can be as out or extravagant or eccentric as they want to be. This is something that we wish we could do in Lebanon, but I think it’s a matter of baby steps if we’re going to continue cultivate this queer scene. Our voices and our presence were too big to keep the scene underground and we slowly moved above ground. But we have to do it first in safe spaces, spaces that we have created before we infiltrate spaces that were not meant for us.

How did you navigate being Arab and queer in the West, and how did this affect your drag?

I definitely catered to a non-Arab crowd when I started drag in New York because that was where I was getting booked. The audience was always American so I would throw in a little bit of Arabic songs or do a little belly dance number to see how people would respond to that. But I also wanted to be relatable to Arab queers. When I was younger, I always wanted to see a representation of Arabness that wasn’t stereotyped as a terrorist or a cab driver. Even more absent was a representation of Arab queerness. I didn’t want the younger generation to go through what I did and have to search for someone to relate to or look up to.

Maneuvering between being Arab and queer has always been a struggle, but through Anya, I have very much overcome that struggle. I surround myself with mostly queer Arab friends in New York, alongside my Arab core family in Lebanon. They get me. They get my culture. They get my references. They get the songs that I do. So navigating these identities is a matter of realizing and accepting them, and finding a way to bring them together.

Dress designed by Anya herself. Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe. Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez. Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

Shifting more to talk about the August 2020 in Beirut, how did you hear about the explosion? What was that experience like?

I was actually in the process of getting in drag. I got a text from a friend here in New York saying, “Did you hear what happened in Beirut? Is your family okay?” These are the kinds of texts you really don’t want to receive as an Arab. The second that you get a message like that from someone, it feels like the end.

I immediately Googled and saw what happened. I had a panic attack. My roommates held on to me as I was freaking out. I grabbed my phone and started calling every single person I know. I called my parents, and got scared because they didn’t answer three times in a row. I called my aunts and uncles and they told me my parents were okay — they live in the suburbs so the glass of their house shattered, but other than that they were unharmed.

Then I remembered that one of my best friends, Andrea, lives literally across the street from the Port where the explosion happened. Andrea is like my baby, she is my drag niece. I started calling her but she wasn’t answering, so I called all my friends and the other queens I knew. I was crying and freaking out on the phone and trying to calm them down as they were also trying to calm me down. It’s crazy to think that anyone has to go through that. Andrea was literally in her bathroom when it happened and her entire building collapsed. Everything is gone. She’s the only one who survived. Someone messaged me that she was okay and in the hospital with injuries, but alive. She had two surgeries. That’s when I could take a breath.

You are not there, but you are. You kind of feel what is happening but obviously you’re not there, so I cannot relate to what it must have felt like. I experienced that with the 2006 War in Lebanon when I was there so I know what it’s like, but it wasn’t as bad as what happened with this explosion.

Seeing my friends and queer family go through that broke me, especially because I wasn’t there for it. For a day or two, I sat across the world looking at the news and constantly making sure everyone’s okay. But after that, I sat myself down, took a deep breath, and realized I needed to do something. I needed to figure out something to help them. It wasn’t just Andrea; so many of my friends’ houses were destroyed, and so many lost everything.

I needed to send some sort of aid but, unfortunately, I don’t have the financial means to do that. But what I do have is a platform. So I sat down and contacted three friends of mine: Dayna Ash, the founder of Haven for Artists; my dear friend Karim Abouzaki, and Mohamad Abdouni, the founder of Cold Cuts magazine. Karim helped me set up an account that people could use to donate and transfer money to the victims. Dayna had gone through the explosion, and the next day she was on the ground cleaning, collecting funds to send to people, and making sure everything was okay. She was the person in Lebanon I could send the funds to to distribute accordingly. Mohamad helped me with putting it all together and gave me advice on how to approach it.

I was shocked at the amount of attention and support that this post got. I was very transparent in the post about how we’re collecting the money and how it’s going to get there. It was like the entire international queer community from the whole world shared it. I had people in Mexico, Portugal, from all over Europe, Australia,Canada etc. contact me and donate.

We were expecting to make around $10K or $15K. This meant that each person that was receiving the funds would get around $500, which meant a lot in Lebanon at the time, which could help people pay their medical bills, fix their apartments, and buy food. But we surpassed our goal and made over $45K in two days! I am someone that didn’t know how to put together a fundraiser but I know how to rally people. I had a platform with only 4K followers on my Instagram and was able to do it with the help of everyone that shared and donated. That showed me the power of social media. It’s a matter of a person wanting to use their platform for a purpose.

We started distributing the money as soon as we got it, moving it through the Western Union to Dayna and then to the recipients. We had a whole excel sheet with everyone’s names and phone numbers, and I knew their stories and what happened to them. We were able to help over 200 queer people, and that is thanks to Dayna who ensured that the funds got to those who actually needed the help.

There were many comments about why this fund was specifically made for queer and trans people, claiming it was inconsiderate as all Lebanese people were affected, not only trans and queer Lebanese people. How did you respond to them?

I received those comments but I don’t like spending time on social media responding to people that are honestly not worth my time. The LGBTQIA+ community in Beirut on a good day already deals with so much oppression and stigma. Now imagine what they are dealing with after an explosion that tore up their city, an economic collapse, and rising cases of Covid. Our mere existence is a threat to society in the Middle East. So, yes, I am going to choose to help the community that matters to me the most, a community that has no rights and is constantly overlooked. There were a lot of organizations raising money to fund Lebanon, but queer and trans people were not going to receive support from those funds. There’s something that’s dehumanizing about constantly having to justify your existence. So keep scrolling hun.

Dress designed by Anya herself. Photographs: Matthew Pandolfe. Styling / Hair / MUA: Anya Kneez. Set Design / Stylist Assistant: Alex Khalifa / The Ballgown Boy / Glossy

Not only did queer and trans people suffer transphobia and homophobia, but it also suffers the consequences of the explosion and COVID-19. Yet it seems like, against all odds, they were able to find hope and joy in drag and performance. Why do you think this is?

That’s honestly the only thing I’ve ever really wanted. I’ve always wanted to belong wherever I was. Whether it was as a gay kid in middle school or a flamboyant gay kid in college or in my queer scene in Brooklyn, I’ve always wanted to find a queer family and belong to it. I searched for it when I was younger and started creating it as I got older.

That’s why I’ve always wanted to create a space for a strong queer community, a strong Arab queer community. We can collaborate, we can make art, we can do things together. I really, truly believe in what they’re doing. Lebanon’s queer scene is very resilient and it has a lot of hope even though their hope has been severely broken down, especially with the explosion. Andrea, for instance, was severely injured, but her face was not touched. She said to me after the explosion, “God loves me because he didn’t touch my face.” That is the kind of resilience and humor that they have to keep upfloat to stay alive. She was in drag again a few weeks later. All of them were. It was their form of therapy and self-expression.

The only thing that really hurts is that the spaces we cultivated are no longer there because of the explosion. COVID-19 meant that all of the people who worked in nightlife lost their work, and then the explosion destroyed the clubs altogether. The community has hope but they don’t have the opportunities. They can do so much more with their drag but many of them are feeling very depressed at the moment, which is why a lot of them are not putting in as much content as they used to.

I think there’s going to be a very bright future for the drag in Lebanon. I started with a friend and now we have over 30 drag queens in Beirut alone, and I think it’s going to keep growing. But I’m very hopeful. Like anything, it’s gonna have its ups and downs. Right now we’re having a down, but I think it’s going to pick back up again. We created this drag scene, we put it on the international map and are uplifting it and then something happens that takes us ten steps back. It’s a constant struggle, but we never give up. That’s what I love about my people. No matter how hard it gets we always find the light at the end of the tunnel.

Video performance by Anya Kneez for My Kali x Yalla! Party Digital party ‘Hopefully Tomorrow’

Looking back at last year, what has changed for Anya?

Honestly a lot, and I think the main factor is that I moved to NYC. Towards the end of my time in Beirut, I began to feel like I have plateaued in my drag career and I was ready for new and exciting opportunities. Thankfully, New York is filled with opportunities. My online presence grew through online performances due to COVID. I think people now recognize me for those music video-esque performances. I work on those videos from beginning to end, and I think that is something people don’t recognize the amount of work that is put into creating a pre recorded performance like that, and I do all of it myself. I am excited to see what the future holds for Anya. I have some projects lined up and who knows maybe Rupaul will finally fly me to LA!

You are currently back in Beirut. How would you describe the changes in the city and the people? How is this affecting you and those around you?

I didn’t recognize the city at all. Not only has it been visibly affected, but the spirit of Beirut is gone. Everyone is trying to live their day-to-day lives but you can tell that they are all hurting. The problem is also that everyone is desensitized to what has happened, everyone is acclimating to the circumstances presented in front of them, but can you blame them? My trip back to Beirut has been an emotional rollercoaster of laughing and crying with my friends and family.

How does it feel to be back home working and performing among your family again?

It feels great to see my family and my queer family again. That was definitely the highlight of my trip. Seeing their beautiful faces again re-energized me and reminded me why I do what I do. I knew I wanted to do a comeback show at Bardo and we did. It was the week before I was about to leave and Bardo gave us a spot on a Sunday night. So I called the dolls (Andrea, Latiza Bombe, Miss Robyn Hoes, and Anissa Krana) and I told them to start prepping. It was an amazing show. The energy in the audience was so beautiful.

I think everyone needed a night like that. People came up to me afterwards to thank me for doing this show because even for just an hour and a half it was a huge escape for them from the daily trauma they are living. I ended the show with a song I have been wanting to do for a while by Majida El Roumi called “Ya Bayrut”. I wanted this to be my send-off song because I had so many bottled up emotions about everything that has happened over there ever since I left. Drag is my therapy and the audience were my therapists. I couldn’t help but cry during the performance and everyone began to cry with me. This is why I love my community. We feel each other’s pain and we stand by each other through thick and thin.

So until we can reunite again… I love you, Beirut.