By Malak Al-Gharib*

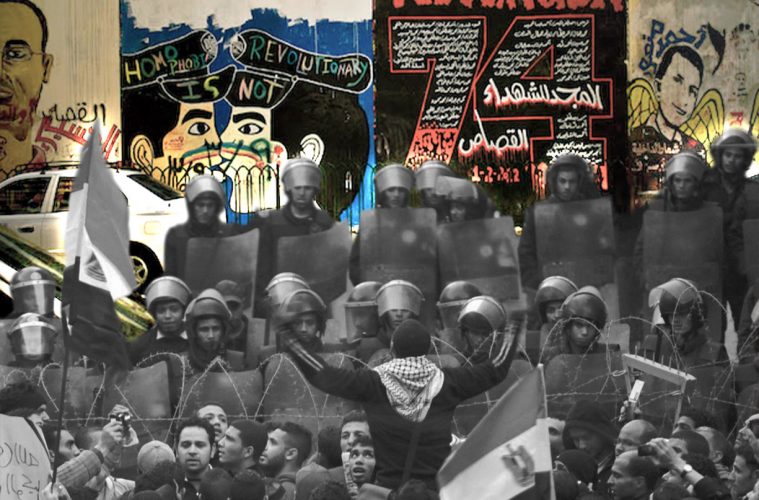

Artwork by Sarah Raji

Translated by: N.H.

Copy edited by Eliza Marks

One of the professors at my university, during his very first lecture, assigned a term-long project that asked us to incorporate what we had learned about media activism with our own ideas and findings. He would then evaluate these projects to gauge our understanding of the entire subject and its pertaining theories. Everything I’d been learning at that point revolved around one topic: “The Egyptian Revolution,” which started on the 25th of January in 2011 and hasn’t yet ended, and this became the subject of my project. In this article, I will tell you our stories, stories that I managed to collect for this project.

History, Documentation, and Memory

One of the participants at a meeting of LGBTQ activists living in Egypt tried articulate the difference between history writing and documentation, but there wasn’t enough time for him to get his point across. Curious, I continued to research methods of oral history collection and the role documentation plays in writing official history.

I realized only then what “history is always written by the victors” meant, that an authority at a specific time writes about a specific historical event within a given set of power relations. This is even reflected in “popular history,” which often reflects the views of the majority, be that a religious, ethnic, or national majority, or of a certain gender of sexual orientation. These versions of history do not necessarily represent all the viewpoints of the people who lived through that specific chapter of history. It only represents the viewpoints of the majority.

What if, however, we tried to look at the experiences of the minorities that lived during certain historical periods? We would be sure to find a fundamentally different view of the events, challenges, and struggles that faced those minorities at that point in history. That is why I decided to talk about myself and my peers from the community (the queer or LGBTQ community), and how we experienced the Egyptian revolution.

We were part of the Revolution since Day One, but many (not all) of the parties and activist circles rejected us later on. They wanted us to participate in the Revolution, but at the same time, they wanted us to remain in our closets to prevent criticism that the Revolution was promoting foreign ideas or ones that opposed societal norms and traditions.

I collected a few stories from these excluded communities, particularly about their experiences of the Egyptian Revolution as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals. I did this as a small attempt at preserving part of our collective memory, which might encourage other organizations, activists, and individuals to participate in preserving this memory on a larger scale. Here’s to hoping for a more inclusive account of the Revolution, one that includes stories from people of all orientations, backgrounds, and minorities, those who participated together in the revolution and who came together, back then, to create a single, indivisible rainbow.

The First Story

I spoke to M.E. on the phone. He was an old friend I had met in 2011, and we had somewhat managed to stay friends. I asked him, “If I were to ask you to tell me about your experience as a gay man during the Egyptian revolution, what would you tell me?”

The question you’re asking is a really hard one. It’s also a sad one. It reminds me of a difficult time. I mean, participating in the Revolution as a gay person! I wasn’t participating as a gay person, though, to be honest. I was primarily participating as an Egyptian citizen. I’m sure my gayness affected my participation and how I interacted with the revolution at the time, but it wasn’t the driving force behind it. Back then, during the January 25 Revolution, when I was going to protests, I hadn’t completely accepted myself yet. I mean, yeah, I knew I loved men, but I didn’t know what ‘gay’ meant or what a rainbow flag signified, or any of that1.

During the sit-ins that started on the 28th of January, almost nobody gave any mind to the differences between us protestors. That started happening after the ousting [of Mubarak] and the years that followed, but you know all that. Whenever I picture my ‘dream guy,’ as they say, I imagine him to be one of the people who were with us there at the square [of Tahrir].

It’s also unfortunate that what happened after the revolution, with the Ikhwan [Muslim Brotherhood] and the army, snuffed out any glimmer of hope when it came to gay rights. As a gay man, I felt that any chance of getting my rights was gone. Living in Egypt puts me at risk, not just because of my political opinions and the fact that I partook in the revolution, but also as a gay man. I could be arrested at any moment for that reason alone. I feel trapped, surrounded on all sides.

After the revolution, there was room to breathe a little. People on social media were talking about homosexuality and gay people, and that helped gay people too. It helped them accept themselves. But in terms of the law, I don’t know if it helped or not. Yeah, gay rights weren’t explicitly on the revolution’s agenda, but when we chanted ‘Bread, freedom, and social justice,’ I believe that the right to our bodies was a part of that, that gay rights and the LGBTQ community were an integral part of that.

“Yeah, gay rights weren’t explicitly on the revolution’s agenda, but when we chanted ‘Bread, freedom, and social justice,’ I believe that the right to our bodies was a part of that, that gay rights and the LGBTQ community were an integral part of that.”

The Second Story

I talked to a friend of mine who’s a lesbian. She welcomed the idea of having her account of the revolution documented and sent me a recorded voice message:

I took part in the revolution since day one, from the 25th of January, and I was there at the sit-ins at the square, as a gay woman, for the entire 18 days. Yeah, we were all in it together, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t get any comments. Even if they were meant as jokes. Comments that I was a bit masculine, especially since I was open about my sexuality. Even before the revolution, I was aware of my sexual orientation and other people knew about it. I’d worked with political parties and movements before, so it wasn’t like I was a new face when I showed up at the square. On the day of the ‘Battle of the Camel,’2 I insisted, more than any other time, to remain in the square and defend it alongside the men. I was emphatically against the idea of the women stepping back and seeking protection from the men. Several people tried to get me to stand back, so I’d be more protected, but I was as stubborn as a mule; I insisted on staying on the front lines, and I fought for that. I hit people and got hit. My leg also got injured, but whatever; I got my way in the end.

I met a lot of gay men and women at the square. They used to come out to me because of how obvious I was about my own sexuality. Sometimes I’d even introduce them to one another, and we’d make tea and stay up late at the square during sit-ins. I continued to meet up with these groups of people for years after the revolution, as friends even. My circle of friends and acquaintances began to expand ever since. Things completely changed two or three years after the revolution, meaning the rule of the Ikhwan and then Sisi’s rule. But despite that, I feel optimistic about the LGBTQ community and gay rights. The younger generation is giving the issue way more attention, and they’re speaking up and raising awareness about a lot of gender and sexuality issues, and that’s a positive thing. Of course, it’ll take time. It’ll be many long years before real change happens, but the path we’re going down seems positive despite everything going on.

The Third Story

This is the story of a trans man who participated in the Revolution:

The Revolution happened on my birthday. My birthday is the day ‘Omar’ was born and the day ‘Gehad’ died. I took part in the Revolution in 2011. Towards the end of 2011, I took off my hijab. In mid-2012, I started taking steps towards transitioning to a man.

The Revolution motivated me to discover more about myself and my identity. I didn’t meet anyone from the LGBTQ community during the revolution, but I did afterwards. On the personal level, I didn’t experience any frustration or disappointment during the 18 days of the revolution, but things became clearer afterwards. There was obviously no place for the LGBTQ community or other groups that were considered to be different. A lot of friends felt frustration and disappointment during the revolution because of what they were told by fellow activists and revolutionaries. They got told things like, ‘this isn’t the right time, and there are higher priorities right now.’

But I think the first real disappointment came on International Women’s Day—the first one to be held after the revolution, and it was on March 8, 2011. I was there, and we were attacked by the Ikhwan and thugs who were still in Tahrir. It was then that I realized that the small percentage of freedom we were under the impression we could get was in fact a big lie, and we still had a long road ahead of us. It’s true that we weren’t attacked because we were part of the LGBTQ community, but the toxic masculinity present there that day made it clear that it was against any freedom of any kind.

This has honestly made me focus more on myself and my personal struggles and problems after the revolution and to work on solutions for them. Being transgender in Egypt already isn’t easy. But the past few years, I’ve been seeing social media campaigns that have been raising awareness about gender and sexuality issues, and that makes me happy.

The Fourth Story

The fourth story is about a trans woman named Jameela:

I was 17 when I took part in the January 25 Revolution. I didn’t just help bring down Mubarak. I also managed to get rid of a lot of the fear I had inside me. My name is Jameela, and I’m a 25-year-old transwoman. Taking part in the January 25 protests was a shell shocking step for me in my personal life. It helped me overcome a lot of my fears, fears that held me back from confronting society, my family, and people in general, with the fact that I am transgender.

The Revolution was a beacon of hope for many members of the LGBTQ community. There was hope that change would come, and that there would be a large capacity for change after the revolution and for tolerance and acceptance of one another. This helped, in one way or another, to increase the visibility of the LGBTQ community in general, whether in activist circles or in civil society. I personally remember meeting a lot of members of the LGBTQ community during the revolution on the streets and at cafes and public spaces. This helped circles expand and increased communication between members of the LGBTQ community.

There weren’t many problems at the time, but many people perceived those who took part in the revolution to be foreign spies who were trying to destroy societal values. Often when a public figure was known to be gay, they were met with rejection from different parties, because they didn’t want them to confirm the assumption that the revolution wanted all Egyptians to be khawalat [fags].

After the revolution, all the different groups that had been united separated to a great degree, especially after the rise of the Islamists and after June 30. Before, we’d been told that the time wasn’t right, and that we should wait till Mubarak was ousted. Then we were told that our rights should wait till the Ikhwan were removed from power. Then it was the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Now we’re being told it still isn’t the right time because of Sisi. This generally pushed the LGBTQ community to work on getting its rights without any solidarity from other political groups.

The Story Continues

The stories I’ve managed to collect during the semester have come to an end, but “our story” still hasn’t. On the contrary, our story continues, and it has extended to other countries, such as Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon, and Iraq. Many queer individuals have participated in our Revolution. In Lebanon, for example, queer participation was more visible. As I mentioned earlier, the aim of this project is to highlight, not document. But I still hope that the project will expand to document the experiences and political history of queer or LGBTQ communities in the Middle East and North African regions in general, especially during historical periods, such as the aftermath of the Arab–Israeli conflict, the first and second Gulf War, and the Arab Spring. I believe that this will play a great role in how our community is perceived, and it will also play a major role in strengthening the intersectionality between political movements and queer movements in the region.

Note: All stories have been modified, including names and some personal details, to protect the privacy of individuals.

Project link: https://soundcloud.com/user-332121482