Words and images by Studio TRQ

This piece is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

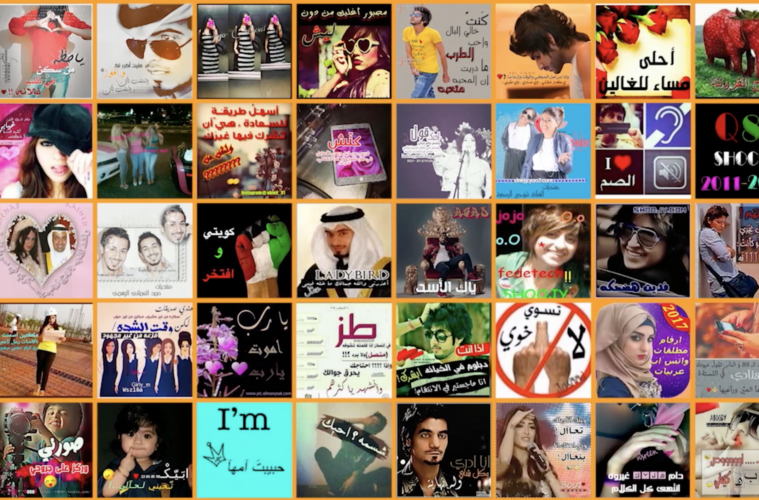

Cringeworthy Blackberry memes, bedazzled floral stickers your elder relatives lovingly (and incessantly) send via WhatsApp, early 2000s HTML forums/“muntadayat.” For years, it was an aesthetic I took for granted, but once named, I realized it encompassed an idiosyncratic visual style that reflected the post-oil Arab world.

The term “Gulf Graphics” was first coined in 2020, with a satirical Instagram account of the same name @gulfgraphixx. The account posted a collection of vignettes and memories from the Arab World’s digital past: BBM selfies with duckfaces, low-quality Bluetooth videos of Bedouin “darbawiya” boys in their Toyota pickup trucks, and garish advertisements and posters for Kuwaiti plays and television shows.

“Gulf Graphics” points to an aesthetic rooted in the extravagant, the experimental, and the unapologetically camp in the true post-oil Arab fashion. The zeitgeist proved receptive; Gulf Graphics inhabited a cultural space that rapidly evolved from the introduction of (and clash between) modern Western marketing and traditional design sensibilities.

Owing in large part to a rich history of artistic traditions, the Arabic-speaking world has always valued dynamic and expressive visual art. As the Internet arrived in the region in 1991, a cultural revolution unfolded. Early blogs and online forums became fertile ground for new ways to communicate and represent Arab identity.

What began as scattered digital experiments evolved into a coherent aesthetic language, what we now recognize as “Gulf Graphics.” This style, born from the intersection of Western pop culture and Arab sensibilities, draws on the gaudy and conspicuous aesthetics of the 2000s such as Y2K futurism and McBling, paired with technological advances in digital editing tools.

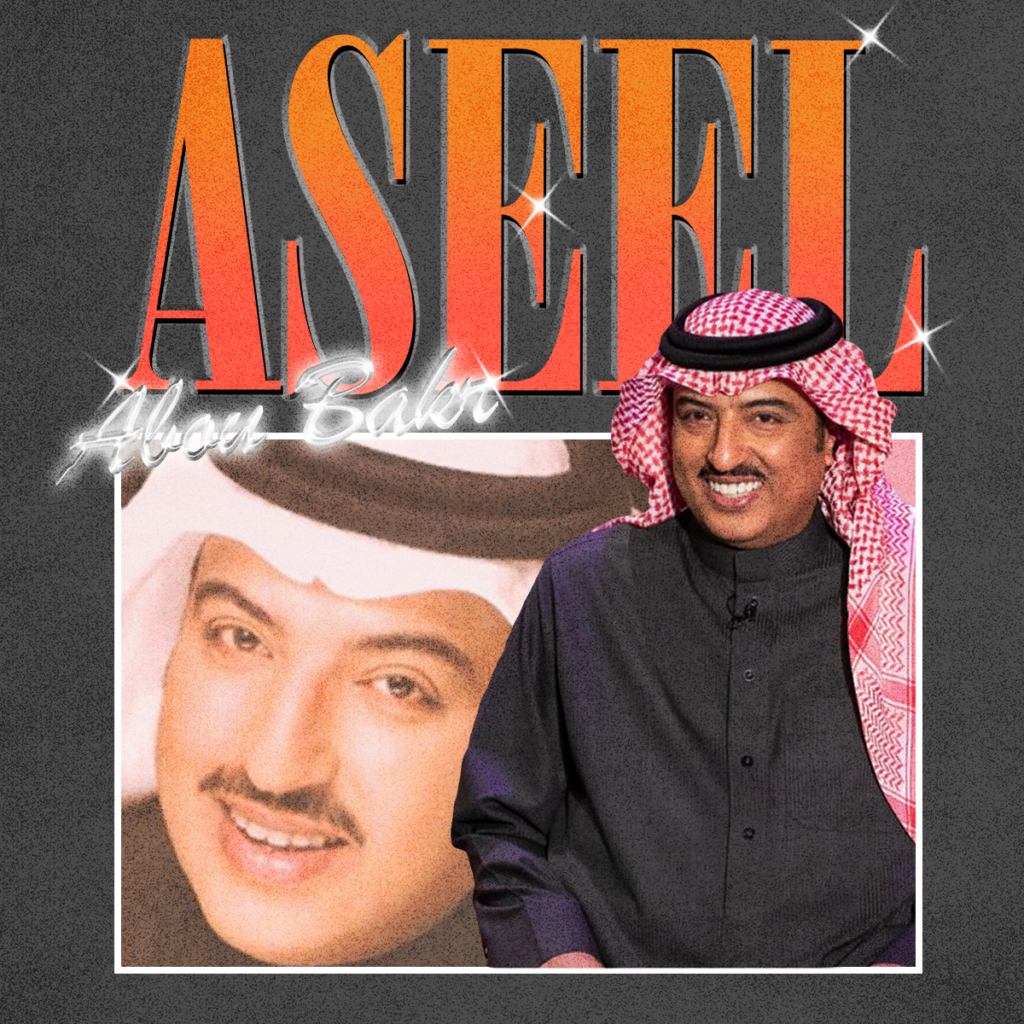

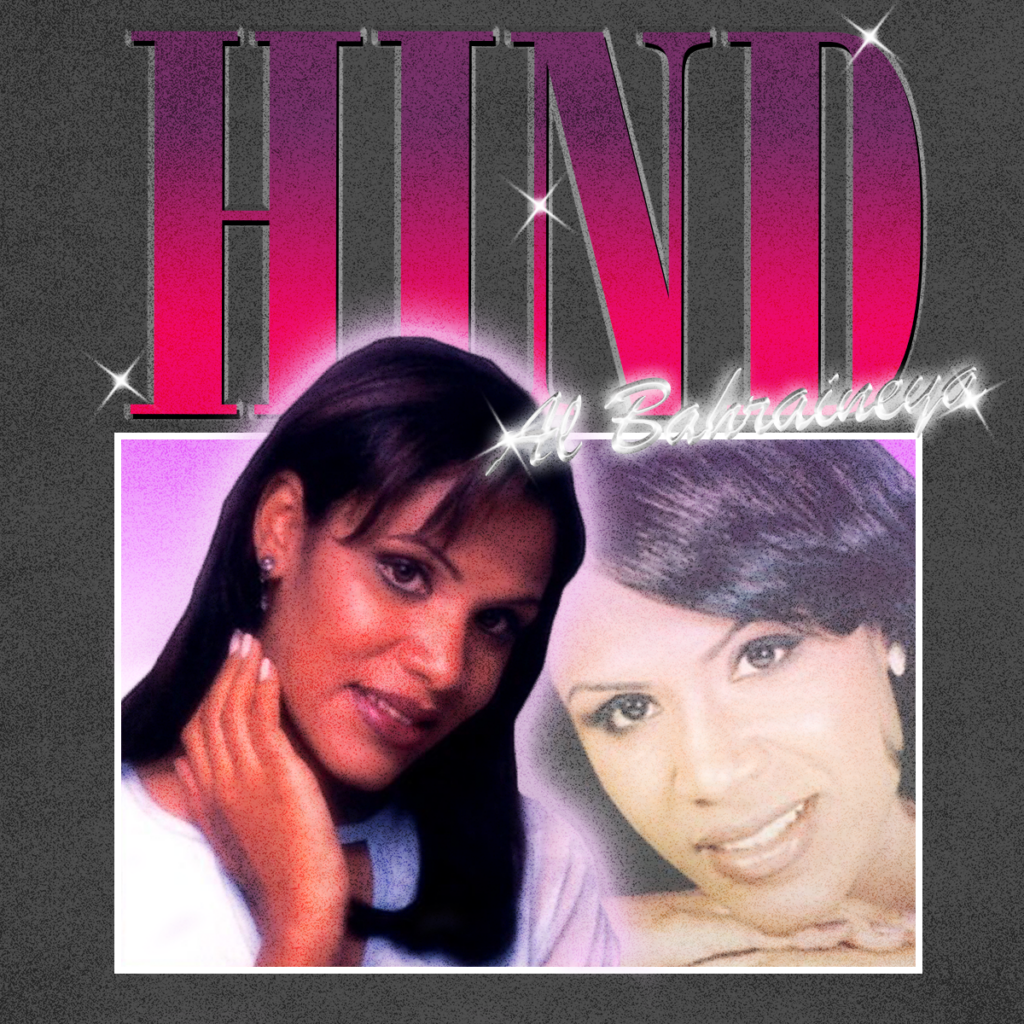

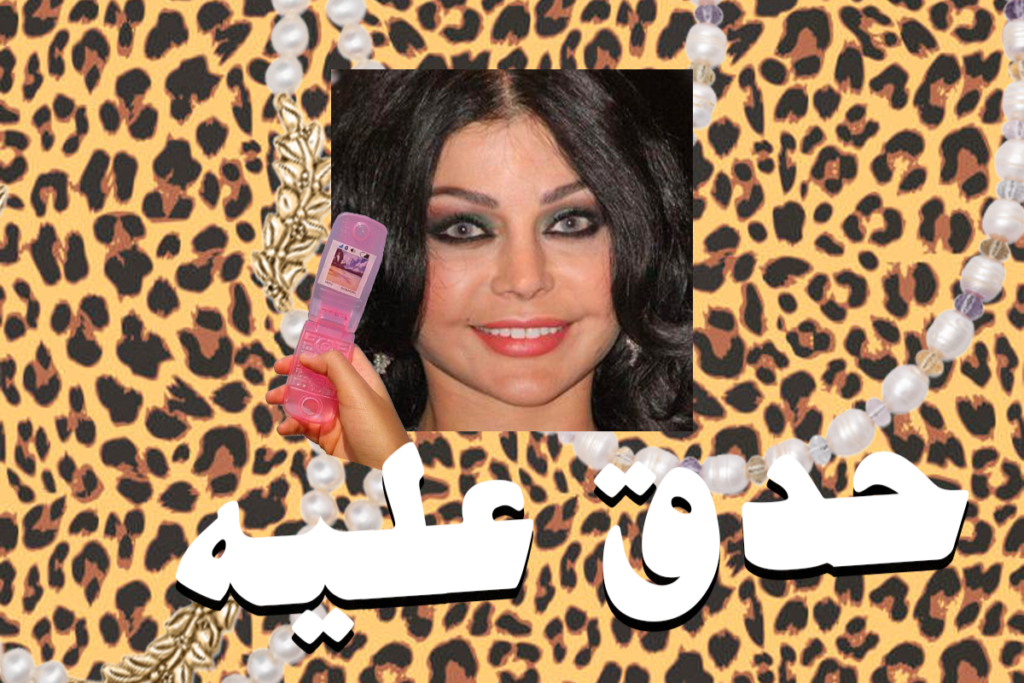

At its core, Gulf Graphics embody the kitsch and camp that Susan Sontag defined in her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp”: “the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” The designs exude a boldness that embraces imperfection and licentiousness. Camp, as Sontag notes, is art that takes itself seriously but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is “too much.” This perfectly encapsulates the spirit of Gulf Graphics: album covers adorned with shimmering text, amateurish photo edits layered with stock image backgrounds, and visual chaos that somehow feels deliberate.

Growing up in Kuwait, I had seen this aesthetic everywhere: on Kuwaiti commercials, on CD covers of Khaleeji, Egyptian, and Lebanese pop divas, and even on flyers advertising local events. To my untrained and childish eye, I never thought of this design style as an aesthetic in its own right, let alone an “Aesthetic” deserving of or qualified for academic study. It was just the visual noise of my middle-class daily life.

Having recontextualized “Gulf Graphics” as an adult, my renewed analysis of it felt like finding a piece of my own cultural history that I had overlooked. Adapting “Gulf Graphics” into my thesis was an attempt to give this intentionally haphazard design style some academic and cultural merit, lest it be lost to the digital ether (as most websites of that era, unfortunately, did, built on crude HTML CSS or now-defunct Adobe Flash assets that refuse to function on Wayback Machine). It further galvanized me to protect and platform it as much as I could: an exploration, elevation, and preservation of a bygone graphic design cultural era.

Part of what made Gulf Graphics so fascinating was its accessibility. In the early 00s, as computers and software like Photoshop became more widespread, design tools were no longer the exclusive domain of trained professionals. Ordinary people began to experiment, creating their own marketing paraphernalia, wedding invitations, and memes. This democratization of design led to an idiosyncratic visual style that was raw, unpolished, and deeply personal. The Gulf Graphics aesthetic was a mode of communication as much as it was an art form, a way for people to navigate a rapidly modernizing world while asserting their proud Arab identities.

Take, for example, the use of typography in Gulf Graphics. Fonts often appear stretched, distorted, or outlined in gaudy metallic Photoshop presets, colors intentionally clash, and textures like animal prints or glitter backgrounds are layered indiscriminately, yet the result feels cohesive in its chaos. These elements reflect a society negotiating the pull between tradition and modernity, between global influences and local roots.

Gulf Graphics also intersected with contemporary gender discourse, particularly in portraying femininity. Female Arab pop stars like Haifa Wehbe became icons of this style, their art saturated with sultry poses and dazzling effects–the shift was very clear once Wehbe came on the scene. These visuals challenged conservative norms while also reinforcing the idea of feminine artifice, women as glamorous and larger-than-life. For Arab counter-cultural communities, Gulf Graphics offered a form of expression that was simultaneously subversive and celebratory; its campy, exaggerated nature provided a space to explore identities that might otherwise remain hidden.

In today’s social media landscape, Gulf Graphics has found a second life. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok are awash with nostalgia for the 2000s, and young Arab creators have embraced this resurgence as a way to reconnect with their cultural heritage. The renewed interest is not merely ironic; it’s a reclamation of an era often dismissed as “tacky” or “naive.” By celebrating Gulf Graphics, these creators are validating a visual language that once thrived in the margins.

My own efforts at reclamation cross a wide scale from creating t-shirts and designs of Arab artists in the style of 1990s hip-hop shirts that you would now find at Urban Outfitters, and video artwork exhibitions that paired Western music videos and their Arab copycats, specifically Nawal El Zoghbi’s “Elly Etmanatoh” being an almost complete ripoff of Spice Girls’ “Holler” visuals. We’ve always tried to recontextualize ourselves as modern and “hip,” even if it’s to our own artistic detriments, but at least we had fun doing it!

As my own artistic eye developed, I no longer saw “Gulf Graphics” as an aesthetic, but as a lens through which to examine larger societal shifts. It reflects the impact of globalization, rising digital cultures, and the resilience of local identities. It’s a testament to the power of design to capture a moment in time and, in doing so, to shape our understanding of who we are.

Gulf Graphics is a celebration of imperfection, experimentation, and excess. It’s a reminder that beauty can be found in the unpolished and the unconventional. And for me, it’s a deeply personal connection to a cultural history that deserves its space in academia and protection in art history conversations, as it continues to evolve, shaping and being shaped by the digital age.

Gulf Graphics Forever.