Words by Dalal Hassane

Featured image: Jableh, Syria, 1997 – My father, pictured right, and his best friend, pictured left

Image courtesy of Dalal Hassane

This piece is part of the “Sana wara Sana” issue

I stood on the border between Iran and Iraq, in the mountainous Hawraman region, which spans across the boundary that arbitrarily carves the lands of my ancestors. A thin, tranquil stream was what separated my feet from one another. It is also what separates two states, two parts of my homeland that should feel separate but couldn’t be more connected.

As my mother and I rode from Halabja to Biyara on the back of her family friends’ pickup truck, the sounds of the Hawrami Kurdish dialect trailed through the breeze, mingling with the traditional Sorani songs blaring from the radio. I thought about how this was not the first journey my mother had taken from Halabja to the border, nor was it the furthest she’d gone. At age six, after the 1988 Halabja Massacre, she and her siblings fled to Kermanshah, a majority-Kurdish city in western Iran. They lived there for three years before returning to the Kurdish region of Iraq, settling down in Slemani after the 1991 Kurdish uprising ended Ba’athist influence in the region.

I write of my mother’s experiences not with authority or certainty, but with a desire to better understand the ways in which her memories trickle into our present.

While my experience with her in Kurdistan brought me closer to a land I’d only heard about from her stories, it also made clear to me the painful reality of my inability to speak Kurdish. Each introduction at a gathering brought my frantic search for my mother, my translator. And, each realization that I couldn’t communicate with the people with whom I share roots in this sacred land made it increasingly clear that a performative and assertive claim to my Kurdishness cannot encapsulate the complexities of my mixed Syrian and Kurdish ethnicity.

I write as someone who in no way believes I have a steady grasp on my identities. It is these binaries that have manifested in the borders that erase my mother’s homeland from the map. Likewise, it is these binaries that have, more often than not, imposed a shallow choice between my Syrian and Kurdish lineages.

Today, the borders that force violent divides in Kurdistan—across Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria—are lands that bear witness to the shed of Kurdish blood. As I write, Turkey is bombing Kurdish civilians in Rojava, Syria’s northeastern region, as it forcibly expands its geopolitical influence in the region. In Iran, Kurdish civilians are being executed for their resistance to the regime after the death of Jina Amini, a Kurdish woman who was murdered by the Iranian “morality” police in 2022. And while Iraqi Kurdistan operates a semi-autonomous government, corruption ruptures its daily life as leaders seal deals with the very oppressors of the Kurdish people. And today, Kurdistan is a land vanished from geographic recognition and instead bears the brunt of colonial and imperialist violence. All of this weighs on how I understand the violence of borders to permeate into family lineages like my own.

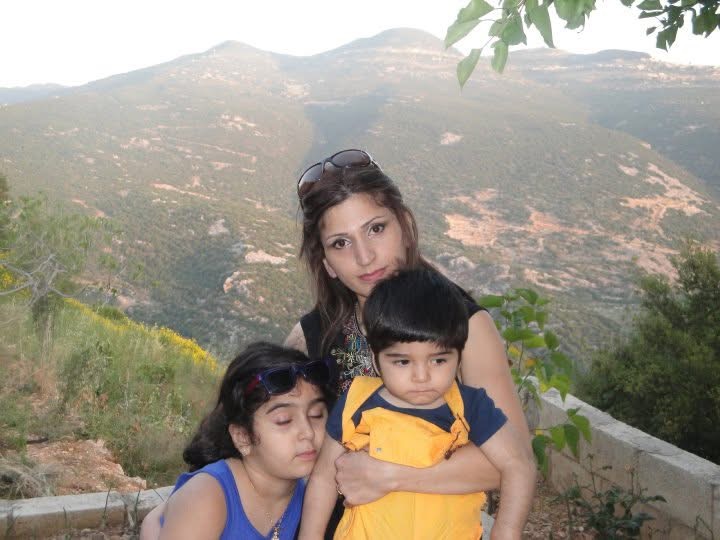

Jableh, Syria, 2010 – My mother, brother, and myself

My father is from the Syrian coastal city, Jableh, a place with endless mountains and beaches. It remains imprinted on his mind despite him not having embraced it in nearly 28 years, not by choice, but to avoid military conscription and decades chained to a bloody dictatorship. The night the Assad regime fell and opposition forces took control of Damascus, one of the first things he said to me was, “Maybe we can go back.”

Overwhelmed with excitement, fear, and uncertainty, like nearly all Syrians living outside, my mind raced with thoughts about the possibility of seeing my father’s homeland for the first time since I was five. I thought about the moment before the blue shores of the Mediterranean come into sight, a moment my father often recounted. I thought about reaching the Qasioun mountains, a sight my parents describe with immense joy and nostalgia.

But each thought of going to Syria brought reminders of the alienation I felt when going to Kurdistan. While I speak Arabic, a fact that many would consider an indicator of seamless integration, my connection with Syria is not an immediate given, much like my connection with Kurdistan.

At first glance, a claim to language appears to be a strong claim to identity. But this does not take into consideration the forces that have prevented my father and I from forging connections to a land subjected to dictatorship for over 50 years. Or, one might assume that my repeated fervent assertions of my Kurdish identity and carrier of my mother’s family histories makes me an unsuspected contender for the title of “Kurdish woman.” But to assume these binaries, as if it is an either-or, is to undermine 20 years of multifaceted reckonings with my roots.

Anthropologist Kirin Narayan writes, “I increasingly wonder whether any person of mixed ancestry can be so easily split down the middle, excluding all the other vectors that have shaped them.”1 An oversimplified expectation to satisfy the labels of either Arab or Kurdish, and never both – which has permeated into many confrontations with my familial histories – has forced a violent divide within my very being.

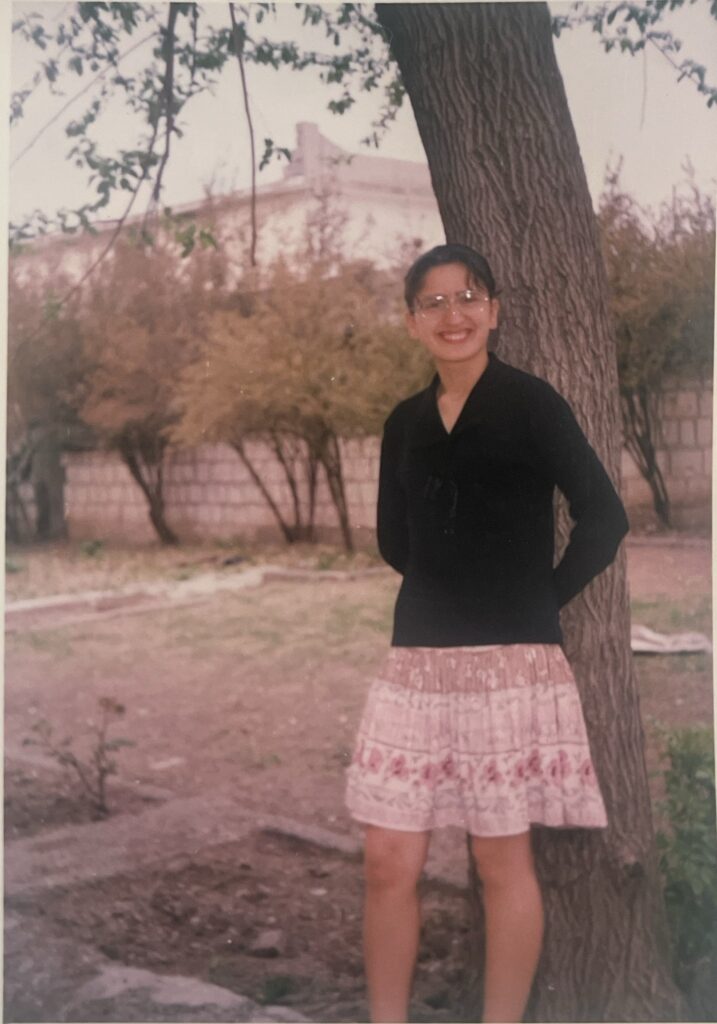

But a supposed divide does not account for what the melding of these identities has taught me about myself, my family, and the lands from which we descend. It does not account for hours of flipping through old photo albums to find photos of each of my parents, years before they met in Syria, their smiles are painted with the youthful embrace of a land that birthed precious memories.

A binary understanding of my identity as both an Arab and Kurdish woman has prolonged this violent cycle of “either-or.” Either I speak Kurdish or Arabic. Either I’m more aware of Kurdish history or Syrian history. Either I’m Kurdish or Syrian.

The supposed binary does not account for difficult conversations we still have, where my two “halves” vie for my pride and loyalty. It does not account for the hours listening to my mother speak of her return to Kurdistan in 1991, when she finally embraced the right to exist as a Kurd in Iraq without fear of persecution. Nor does it account for my father sharing his favorite Syrian songs, which defied the regime’s attempts to sever his connection from Syria.

Slemani, Kurdistan, 1998 – My mother

As I watch from afar as my father’s land reckons with the aftermath of a half century of Ba’athist terror, I’m reminded of my mother’s experience growing up in Kurdistan under the Ba’ath party. More than ever, I realize that my Syrian and Kurdish roots are not mutually exclusive labels to be attached when convenient, but encapsulate a family history between neighboring lands, both of which are yet to be freed from imperialist violence. And, they present a challenge to those who believe a lineage like mine warrants outrage.

People like me should not feel ashamed of yearning for a deeper connection with their homelands, nor a fear of not understanding it fully. My identity as a Syrian and Kurdish woman is one I carried with me when I first visited Kurdistan in 2021, and it is one I will carry when one day I visit a Syria free from Ba’athism. When my father and I catch a glimpse of the sea from the winding roads of Jableh, I will not think of boundaries that sever two precious parts of myself, but of the joyous rides along the Hawrami mountains with my mother, as we basked in the night’s endless sky.