Words and artworks by Habiba Haddara

Featured Salon image by Bushra Mettawa

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

This article is part of the “My Hair My Hair” issue

“Your voice was mine, my hair was yours” (2022) is an ode to the many feelings that have been left unspoken throughout my youth. In this piece, I’m desperately trying to give voice to an indefinable feeling. I question what mother means, knowing that the term will always be open-ended and too large to absorb. In exploring the meaning of mother, I question my own selfhood. I find Audre Lorde’s words on the erotic echoing in my mind, thinking about how I had thought that my strength is derived from its suppression and separation from the public realm and from myself.

Photography by Habiba Haddara with the help of Aisha Azab and Martina Ashraf

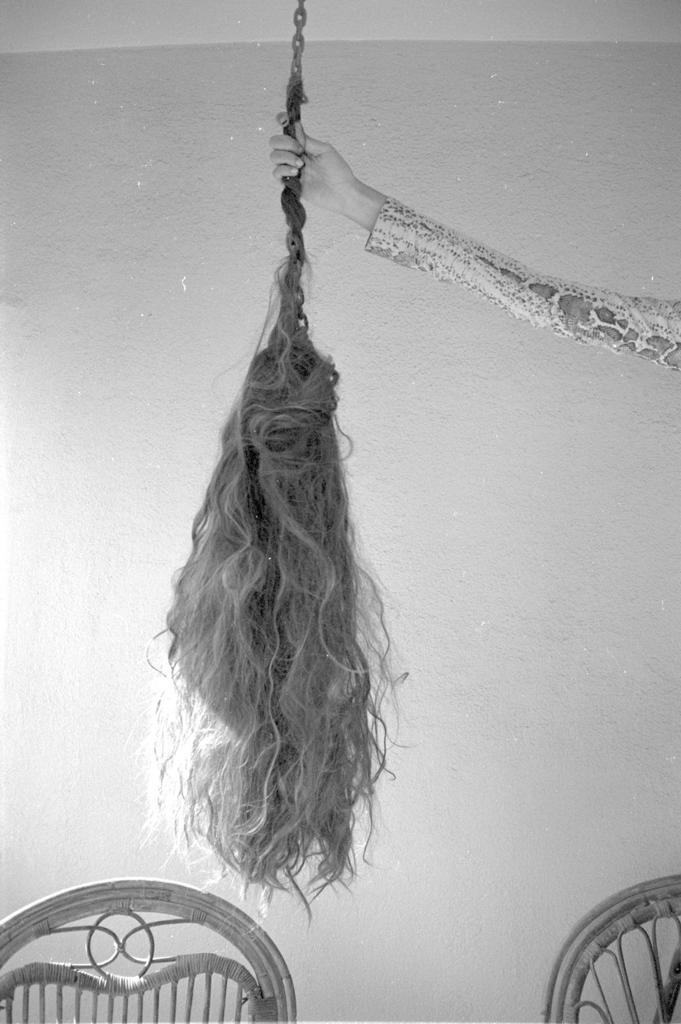

I produced a rug in an attempt to give these unresolved feelings space and to make pain visible. In this piece, told in four chapters, I unravel the story of the hair-sewn rug: braids frame the piece, the blade-like spikes of hair that fill its corners, the roots down near the follicles, and then the draping of achieved separation.

Using hair as the main medium, I played with form to illustrate the inextricable connection between narrative and the body, itself as a form of narrative. In considering the body-as-narrative – and by extension, hair – I also consider the audience entailed in its observation. Building on these concepts and realizations, a story unfolds.

Photography by Habiba Haddara with the help of Aisha Azab and Martina Ashraf

Chapter 1: My Braid

When I was younger, I had deemed myself incapable of any handwork. I watched people learn to braid and felt daunted by the prospect of doing it myself. I felt like others had smarter bodies or more dexterous hands than mine. But still, we all learn to braid eventually. I learned in the backseat of my mother’s car on my way back from my grandma’s house; I thought my hands finally understood.

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

The three strands wove together, and it became like an obsession, fixation, and point of pride; my braiding signaled the intelligence of my body.

Brushing my hair was always a nightmare – it was long, thick, and damaged. Still, my mother would occasionally take pleasure in de-tangling it after I’d shower. I remember the painful process of the hair detangling and slowly coming together to form a braid, her hands moving effortlessly.

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

Chapter 2: Blades

Throughout my youth, I needed to be rid of my hair. I didn’t shave because I had heard that it was bad because the hair would grow back thicker. So I waxed; my mom would buy me Veet wax strips.

The hair was dark and so deeply attached, standing out like sharp blades. No matter what I did, the hair never stopped growing. I deemed myself incapable of getting the waxing process right, so my mother would help me; she would make sure every little hair was removed, redirecting the hair, smoothing the surface, and pulling. No one but her could wax my armpits.

The process was so quick yet so extremely difficult. I remember the violence I associated with the pulling up of the roots. I legitimized it by thinking that the more pain I felt, the more time I had guaranteed without the hair. And then this agony would be forgotten as if it had never happened at all. It was like a self-inflicted, terrible but fleeting pain that I could live with.

Chapter 3: Roots

As my body grew, I learned how to look at myself. I’ve since been working to unlearn this conditioning, but I seem to look more curiously and precisely the more I try to do this.

The more hair feels frivolous or trivial, the more I see. I saw not only how it frames my face when it’s sparse or dense, but also where hair follicles collide and where they separate. I explored where the roots attached and how the hairs grow out, standing closely together.

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

I remember thinking that my entire life, I had been told to brush through the roots. The time I had lice, I had to brush my hair several times a day, starting from the roots until I could feel my scalp water. During my teenage years, in an attempt to avoid this, I would start detangling from the ends and work my way closer to my scalp.

Though they were a point of attachment, I avoided the roots because they could be scary and ugly, and deeply painful. But, in an attempt to see beginnings, this third chapter honored the hair root, spare yet thick, deeply disturbing, yet there nonetheless.

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

Chapter 4: Drapes

As I approached the last chapter, I made it a point to get more comfortable with the untangling of the braid. Understanding that the braid is not an indication of distance, I told myself it was time to separate.

During that time, I slowly started to redefine what distance meant; it isn’t a mental process as much as it was a moment of seeing. Observing my body and the way hair is always present in flux. I made an active decision to leave my braid. Intentionally engaging with the meaning of separateness has been devastating and frightening. I realized how safe a braid is, existence is collective. I know how comfortable I grew with my own braid of sorts. I was begging to leave while simultaneously waiting for the next braid to live in.

CONCLUSION

I realized that there is no final form and that the process of shifting body and hair and identity is not irreversible, in itself. I have come to find that the same form allows for many meanings to (co)exist at the same time and that these meanings continue to shift between the tangible and ambiguous with time. I can comfortably make meaning even when it feels out of reach.

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam

In understanding the aspects that combine to create a braid or undo it, I make sense of the fluidity of separation. I think about Audre Lorde when she said, “Your need to reach down and touch the things that are boiling inside of you and make it somehow useful.”

Photography by Eslam Abd El Salam