بالعربي

Words by Ola Haj-Hasan

Translations by Hiba Moustafa

Design by Lina A.

This article is an outcome of a writing workshop conducted by My Kali magazine

Men in the Sun (Rijāl fī al-Shams) (1963), a novel by Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani, follows three Palestinian refugees seeking to travel from Iraq to Kuwait, where they hope to find work. The novel is loaded with symbolic details and hyperrealistic elements. So, too, is the film version, The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un) (1972), produced by National Film Organization in Syria and directed by Tewfik Saleh, which stays generally true to the novel, except for some differences that my review will highlight.

The main characters of the novel and film represent three generations suffering from the continuation of Nakba in their lives. Abul Khaizuran, the driver who smuggles the three men in his lorry’s tank, symbolizes Arab and Palestinian leaders who enjoy a relative prosperity, benefitting from refugees. His castration by shrapnel of a Zionist bomb in 1948 is often interpreted as a metaphor for a state of socio-political impotence that leads Palestinian youth to their death.

This review aims to revisit these interpretations by placing the novel and film into a wider context.

Men without Fathers

Starting with the title, Kanafani presents his characters primarily as men, introduced by their age. Each has his own chapter that bears his name, tells his story, and explains his position in the family system. The film, however, strips the characters of this classification and introduces them simply as “dupes”. It opens with the title, The Dupes, displayed against a backdrop of a barren desert with a skeleton lying on the sand, followed by the verses:

My father once said:

He who has no homeland

Will have no sepulcher on this earth

And forbade me to leave!

These lines, quoted from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s “My Father,” foretell the characters’ destiny even before their journey begins. On one hand, it destines their project to failure, and, on the other, it judges them from a paternalistic point of view. The film sets us up to meet not “men in the sun,” but deluded ones straying from the father’s advice.

The question, however, is which father could have advised these men/dupes? One of these men/dupes, elderly Abu Qais, is himself a father who decided to take risks to provide for his children. Another, Assad, is an orphan whose uncle lent him money to travel from Amman to Baghdad so that he will eventually marry Nada, the uncle’s daughter. In the novel, Kanafani describes Assad’s situation, writing:

Who told him that he wanted to marry Nada? Just because his father had recited the Fatiha with his uncle when he and she were born on the same day? His uncle considered this was fate … Who told him that he ever wanted to get married? Here he was now reminding him again. He wanted to buy him for his daughter as he buys a sack of manure for the field. He tightened his grip on the money in his pocket and got ready to get up.

We can feel Assad’s revolution against the father’s authority and his rebellion against fatalistic customs, traditions and culture represented by his uncle. He goes as far as rejecting the institution of marriage in its entirety. The film rearranges these ideas by attributing them to Assad, who says them to his older brother, a character that does not exist in the novel. The brother respondes:

Stay here, Assad. This is your place; don’t run away. Oh brother, don’t run away. Complete the path we took together. The case requires a lot … None of these problems will be solved from there. Problems will not be solved on their own; one must not escape from them.

The older brother character in the film embodies the ideology that opposes refugees’ immigration in principle, seeing it as a running away. This is consistent with the film’s overall portrayal of the characters as deluded smuggled men. The older brother, here, also plays a role in imposing paternal dominance and guardianship on Assad; he preaches Assad, holds his hand as they talk, and then catches up with him when he gets up, putting his hand on his shoulder.

As for the third man/dupe, Marwan, his father married Shafiqa and moved to her concrete-roofed house, leaving Marwan, his mother and his siblings behind and relinquishing his responsibility towards them. This responsibility became Marwan’s when his brother stopped sending money from Kuwait after he married. In the novel, the weight of this responsibility was only lifted when Marwan called his father a “despicable dog” in a letter he sent to his mother. This is how Marwan rebels against the father’s authority; he does not want to cross out his rebellious words “not only because his mother would see the crossed-out words as a bad omen, but also, quite simply, because he didn’t want to.” In the film, the letter is replaced by Marwan’s words, “My dad’s deed was a dirty one,” which do not inspire the same power he gained through his declaration and breaking the father’s image in the novel.

It is worth noting here that Shafiqa had lost her right leg during the bombardment of Jaffa, and she is the second character in which dismemberment manifests itself as a metaphor for loss. But, unlike Abul Khaizuran’s castration, her amputation neither has moral consequences nor leads to suspicious life choices. Her only problem, from her father’s point of view, is that men do not want to marry her.

The Castrated Leader

Abul Khaizuran’s castration is a turning point for his moral compass. He was a fighter when he stepped on a bomb that castrated him in 1948, and after the incident, he became a smuggler across the Iraq-Kuwaiti borders. Even before knowing of his castration, we know his philosophy: “Money comes first, and then morals.” Once the castration is revealed, his greed is presented as a psychological need rather than an intellectual attitude. When Assad asks him why he is in the smuggling business, he answers after an attempt to evade it, “Shall I tell you the truth? I want more money, more money, much more.”

We can interpret his interest in money as a phallic obsession through which he tries to compensate for his lost manhood. This is further illustrated in the sequence of his thoughts as he recalls the moment of castration:

There was a woman there, helping the doctors. Whenever he remembered it, his lace was suffused with shame. And what good did patriotism do you? You spent your life in an adventure, and now you are incapable of sleeping with a woman! And what good did you do? Let the dead bury their dead. I only want more money now, more money.

In the novel, the castration incident is introduced by a spontaneous question. Assad, “Tell me, Abul Khaizuran. Have you ever been married?” to which the latter loses himself in his thoughts, feeling a terrible pain between his thighs and imagining his legs tied to two supports that kept them suspended, and evades giving an answer. In the film, Assad’s question takes more precise terms, “We have laid our destiny in your hands … You’re our leader. We depended on you like, I don’t know how to explain it … are you married?” These words are centered on patriarchy, which seems essential in the way the director handles the text, for the leader is the father and the father is the leader. And the question about marriage here is a key to talk about legitimacy and the extent to which responsibility is taken.

The film depicts Abul Khaizuran too as if he, in Darwish’s words, did not have a father to forbid him from traveling. He recalls a conversation he had with a friend – a character that does not exist in the novel – who tells him, after the castration incident, “Does running away ever solve a problem, Abul Khaizuran? Running has never solved a problem.” It is not clear whether what he means by “running away” is being in smuggling business, or, as in the novel, leaving the hospital before he is fully recovered. Leaving the hospital would represent a state of denial or, more accurately, a state of rejection. The novel is keen to distinguish between the two: “Hadn’t he accepted it, or was he incapable of accepting? From the first few moments he had decided not to accept.” This gives Abul Khaizuran a kind of agency the film denies him.

This additional character, like Assad’s older brother, rearranges the ideas offered by the novel’s monologues. It also adds a level of guardianship, as is seen with Abul Khaizuran’s friend starting his lines on a dark screen then guiding viewers from darkness to light by lighting a lamp. Abul Khaizuran kicks him after he says, in a shaky voice and a performance that tells of weakness, “What have we gained? Manhood is lost and everything is lost.” Unlike the film, which presents Abul Khaizuran’s castration within an aura of despair, the novel opens the way to interpret it in an angry or sarcastic tone: “For ten long years he had been trying to accept the situation? But what situation? To confess quite simply that he had lost his manhood while fighting for his country? And what good had it done? His manhood is lost and his country is lost.” Time plays an important role here. Whereas the film directs us to Abul Khaizuran’s psychological state immediately after castration, the novel presents a large span of time from the castration incident to what has happened since. Moreover, in the film, the castration is presented as collateral damage of the loss of his homeland, while in the novel, it is depicted as an additional price that Abul Khaizuran paid, which places him in a position to come to terms with the status quo.

One of the most prominent features of the castration moment is Abul Khaizuran losing his voice then screaming, “No. It’s better to be dead” in response to the anesthetist placing a gloved hand over his mouth “muffling” him during the operation. His anger towards patriarchal medical authority becomes clear when he says, “They don’t know anything, and then take it on themselves to teach people everything.”

It is interesting that both the plots of the novel and film bring up castration flashbacks while Abul Khaizuran drives his lorry, with the image of the light above his head in the hospital mingling with the image of the sunlight that makes it difficult to see in the desert. The dynamics shift and Abul Khaizuran becomes in control, just as the anesthetist was, claiming that he knows the best interests of the men in the tank and muffling them.

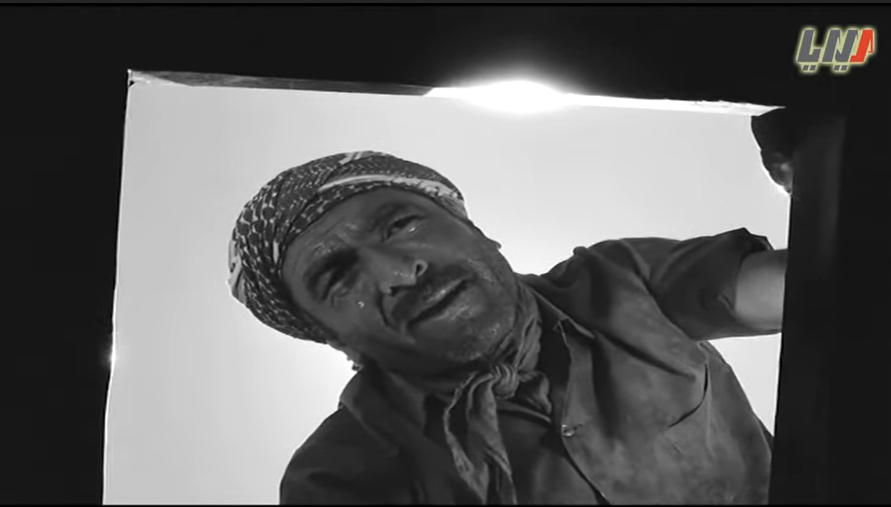

Outtakes from film; The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un) (1972)

Death shows itself in the film, too, when the three men/dupes agree on traveling. Abu Qais says, “Either we live together or we die together,” to which Abul Khaizuran responds, “Why are you talking about death when I’m the driver, man? I’m the leader; you should put your trust in me. Count on me and say nothing about death.” This dialogue is absent from the novel and further serves to depict the characters as deluded.

The notion of death is essential here, for if Abul Khaizuran had died instead of being castrated, he wouldn’t have led the three Palestinian men to their death. This is particularly true because their death was directly caused by the Kuwaiti border officers’ stalling Abul Khaizuran over a rumor they had heard about his sexual relation with a dancer named Kawkab. Maybe if their stalling was in a different context and did not trigger his trauma, he could have put an end to it before it was too late.

Why Didn’t They Knock on the Sides of the Tank?

This question is perhaps the most quoted line from the novel, but my interest lies not in the answer but in its being asked by Abul Khaizuran. If this question were truly the ultimate “moral of the story” or the concluding metaphor of the absurdity of free death, then it would have been said by the narrator. Even if it had to be said by Abul Khaizuran, this should have been at the moment he discovers the three bodies, not after he takes their possessions and dumps their bodies on the side of the road.

In this context, Abul Khaizuran’s question reveals the difference between himself and the three men: he cannot comprehend their dignified silent death. The film, on the other hand, dismisses the question; the dupes knock on the sides of the tank but no one hears them. If we took the relation between castration, death and running away into account, we could assume that their death in the novel is their escape from metaphoric castration, loss of manhood. As for their death in the film, it is the castration done to them by Abul Khaizuran, of which death is a byproduct.