By Majeda Mahasneh

Translations by Hiba Moustafa

Design by Lina A.

This article is an outcome of a writing workshop conducted by My Kali magazine

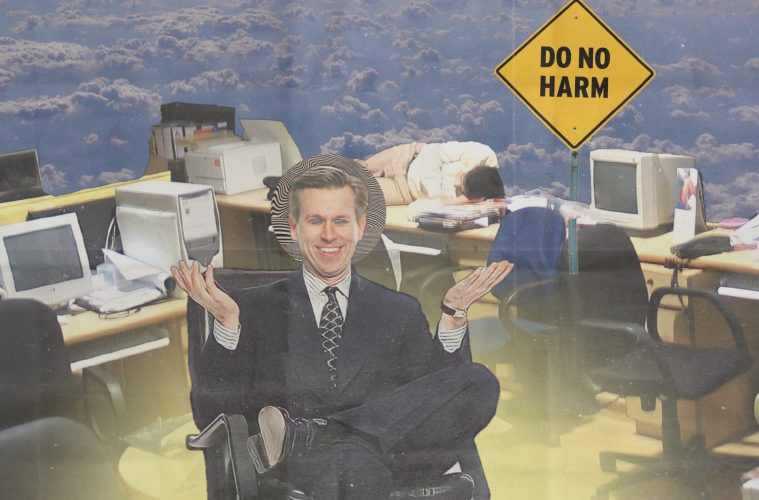

*A fundamental principle in humanitarian action framework, “Do No Harm” specifies that humanitarian assistance may not be given unless the wider context of a given case is duly considered and assessed in order to mitigate potential adverse impacts.

Those of us destined to work as public and private sector employees cannot but hope that the “machine” is merciful enough to leave us space among the heaps of tasks to ask, “Are we OK?” It is a grinding machine, a dominating tool characteristic of various sectors in the capitalist world that reduces the existence of employees in the workplace to customer satisfaction, tasks accomplishment or achieving the so-called “target.” No doubt, each one us ground by the machine develops special capacities, and, in time, we adapt to learn skills to help us deal with the machine and its impact on us. Some of us escape the pressure by dodging it; others confront mental burnout every working day, leaving their fingerprints on the scanner that awaits them as they enter and exit.

During my research on employment in these work regimes, I used the “Do No Harm” humanitarian action framework to investigate the impact of beneficiaries’ cases on frontline workers in humanitarian organizations in Jordan. I interviewed two NGO and INGO employees about their experiences in humanitarian work, the impact on their personal life, and how this has altered or affirmed their path.

Huda is a case manager for survivors of gender-based violence (GBV), a form of violence women face at much higher rates than men both in host and refugee communities. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) that humanitarian organizations work in Jordan follow define GBV as “Any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e. gender) differences between males and females.”1 It was not surprising, therefore, that Huda was a survivor of GBV herself before engaging in humanitarian work. This brought her face-to-face with her previous traumas, and she found similarities in hundreds of survivors’ stories. This became an affirmation of human cohesion among stories of similar cruelties, and Huda’s own mental strength allowed her to help emancipate the powerless. Though the organization did not offer specialized mental health care appropriate for the nature of staff’s work, a year ago, Huda received technical training on building workers’ capacity to handle “cases” more sensitively.

Huda confirmed that the indirect and direct pressure exerted by the management, her daily interactions with abused women, and the large amount of required office and field tasks have caused her mental exhaustion. And, the workplace stress that has emerged in response to emergency cases has impacted the quality of the service provided. Huda acknowledged she has not provided sufficient service to some beneficiaries because of the limited ability to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the case. “I take the case’s call, but I don’t have the patience to listen and react … For a time, I used to work at home to meet a target. And we stay late at the office. There is no balance. I cannot have time for myself.”2

Nader had a very different experience as an “access worker” at an NGO, where he conducts networking and community mobilization activities. Over the past seven years, it has brought him closer to the challenges faced by LGBTQ+ people, and the assistance he is able to offer is a source of energy. He says that the work has had a positive impact on his life and is part of his unique lifestyle, and he devotes time outside office hours to continue his work and does not care about receiving specialized psychological support. What matters for him is having his voice heard and that the organization recognizes his work and contributions.

Expectedly, the impact of individual cases on Nader’s mental state differs greatly from Huda’s. Due to the sensitive nature of working with LGBTQ+ people, Nader’s organization needs to ensure it adopts humanitarian principles to offer effective services, maintain sensitivity while interacting with LGBTQ+ people, and create appropriate codes of conduct and protection policies. They offered employees a self-care workshop where they learned about mental health, exercises including deep breathing, simulation, and role playing. It is also essential for employees who bear the emotional burden of working with survivors to have a space away from the office, papers, and beneficiary reception centers. Staff mental health programs include engaging in group discussions about work-related challenges and the feelings related to daily experiences with the organization, system, and beneficiaries. This provides space to receive feedback that can become useful in future projects or phases, and to prioritizing staff’s wellbeing.

At one point, when he felt stressed by a beneficiary’s attachment and desire to be friends, Nader approached the organization’s psychologist. However, Nader is more tolerant of the management’s general failure to provide employees mental health care programs, and a dinner or a quality time with the team outside of work is enough to give him energy and promote a sense of belonging with colleagues and even management. For Nader, supportive and understanding colleagues have been the most important thing to preserve his mental health and satisfaction with work even when he faces the management’s pressure to meet a “target.” “Sometimes, the pressure is too much. They wanted to hold workshops and meetings with the cases, but I was terrified of contracting Covid-19.”3 Nader’s love for working with vulnerable populations and those in need goes beyond the organization itself; he helps beneficiaries safely but informally, from providing job and training opportunities to referrals to physicians and specialized clinics. Nader says that the only people affected by his engagement in his work are his friends, who complain about his constant absence.

Nader is much more lenient with his management’s failure to provide mental health services to employees than with its “hands-tied” methodology when providing professional services to LGBTQ+ beneficiaries. He is dissatisfied with (trainee) therapists who are hired to deal with a variety of delicate cases regarding the LGBTQ+ people’s interactions with their families and society. “Therapists gain experience, but their presence is an obstacle. I know they lack experience and knowledge of LGBTQ+ community … not to mention the babbling and gossips … Beneficiaries become guinea pigs.” The pressures and challenges beneficiaries face requires several sessions and intense follow-ups, but they don’t receive these. “There need to be more mental support sessions; one or two hours is not enough. There has to be sufficient follow-ups… There is no continuity!”

When I asked Huda if there were employee-specific mental health programs delivered in a timely manner, she turned her attention to the people in management rather than the system itself. “The management itself is not aware how important self-care is for employees. If there were any awareness or a fixed system, there’d have been a special department for staff care or networking with other organizations. It depends on who is in charge.”4

Work pressure often continues, pushing Nader and Huda to create their own ways of adapting and venting. Interacting and communicating with beneficiaries effectively requires listening and responding to the mind and body’s urgent needs for rest. Huda resorts to simple, inexpensive and mostly intangible ways. “I go for a walk. I listen to music. I do my old activities to see if they have the same effect as before, like smoking hookah and dancing. Crying helps, too. I watch a comedy to get away from the work’s mood.” Meanwhile, Nader keeps recharging his energy through his extensive interactions with beneficiaries. “… The more I help and see that a case comes to me and trusts me, the happier and joyful I am.”

Staff members also bear the onus of accommodating turnover of management, particularly when working on externally-funded projects. This means a lack of job security in cases when current projects are not renewed or donors reject proposals that have been underway for months for the sake of expansion or widening its reach. These shifts can also occur as part of other changes, including restructuring, downsizing, or a need to secure salaries for current employees before catering to mental health needs that result from the work.

Humanitarian organizations need stable management to improve the performance in systematic ways by designing trainings and programs that support staff’s mental health.

My interviews with Huda and Nader reveal that the challenges we face as human beings, whether employees or beneficiaries, are similar and intersecting. Both employees and beneficiaries feel vigilant when facing challenges in reception centers, where beneficiaries attempt to attain services and service providers resist mental burnout. This burnout comes from the stress of their work when providing psychological first aid, and the organization’s intentional and unintentional neglect in responding to the strain on employees.

Employees’ dedication should not preclude their chance at receiving appropriate care. The DO NO HARM principle should apply to employees in the humanitarianism setting without being governed by “targets.” This is necessary so that neither employees nor beneficiaries fall within the “machine” and so that they are able to provide a “safe haven” to support survivors effectively.

References and resources